Technology-Based Learning Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readytalk for Online Meetings

ReadyTalk for Online Meetings Online collaboration with colleagues, partners and customers is effective and easy with ReadyTalk’s audio and web conferencing technology. Audio & Web Conferencing Audio & Web Conferencing audio and web conferencing Save Time and Money with Conferencing Cutbacks in business travel, more flexible work schedules and advances in technology have increased the demand for and value of online collaboration. The ability to easily join an audio and web conference and view the same content, applications and documents is no longer a “nice to have.” It’s a business necessity. All the Tools You Need Effective online meetings require a conferencing platform that is easy to use and reliable. With ReadyTalk’s audio and web conferencing, you have full access to the tools needed for polished sales demos, customer training and remote meetings. Easy Access for Everyone Start meetings faster and on time. Participants with Flash join your meeting in less than 10 seconds with no downloads and an alternative auto-installing Java application means those without Flash can still attend. Plus, superior platform (Windows, Mac, Linux) and browser (Internet Explorer, Safari, Firefox, Chrome) support means everyone can join. Industry-Standard Recording Formats Capture the details of the meeting by recording the session. Recordings are available for download in four industry- standard file formats: Flash, .mp4, .mp3, and .wav and can be hosted on your servers for future playback or sharing with colleagues. ReadyTalk Offers a Full Range of Services: Audio Conferencing, Web Conferencing, Recording and Archiving 1 Start your meeting with ease. Whether you want to meet now or plan ahead, ReadyTalk makes it easy for you to start your conference and easy for your participants to attend your meeting: On-Demand Meetings Conduct an online meeting instantly – simply log in to ReadyTalk and dial in with your phone. -

Web Conferencing Comparison

Web Conferencing Comparison We offer a range of web conferencing solutions designed for use with different types of meetings: from less formal on-the-fly get-togethers to carefully structured company-wide conferences or training sessions. Unified Meeting®—let people see what you are talking about and collaborate during your online meetings with our proprietary web conferencing product. You get audio, web and video conferencing in a single system that integrates with everyday business tools, like calendaring systems and instant messaging clients, so starting and joining meetings is done just with a click of the mouse. The best part is that all of this comes as a service that is managed for you. Microsoft® Office® Live Meeting—host interactive, collaborative meetings by showing presentations, software and web sites. Office Live Meeting offers unique features, such as muting lines and dialing additional participants from the web interface, Microsoft Office integration, custom slides, reporting tools, recording and printing to PDF. It’s a flexible tool that can be configured to suit the needs of your conference—no matter what size or type. Cisco WebEx™ Meeting Center—engage your participants by sharing a PowerPoint presentation, demonstrating software, showing web site navigation, asking polling questions and transferring files. The integration with Reservationless-Plus® lets you control the audio portion of your meeting online. WebEx Meeting Center provides the ultimate collaborative platform for your day-to-day business communication needs. Cisco WebEx Training Center— deliver live, interactive training sessions with features specifically designed with the virtual classroom in mind. In addition to sharing presentations or demonstrating applications, you can conduct quizzes online, separate trainees into work groups for collaborative projects and host post-training tests for follow-up. -

Easing the Transition Into Remote Working Maximize Collaboration and Productivity with Voip and the Right Technology Tools

Easing the Transition into Remote Working Maximize collaboration and productivity with VoIP and the right technology tools www.3cx.com CONTENTS 3 Introduction: Remote Working is the New Reality 4 Remote Working Challenges 5 Benefits of Working Remotely 6 Why VoIP is a Must-Have for Effective Telecommuting 8 The 3CX Advantage 10 Tips To Choose The Right Business Communications Solution 11 Conclusion Remote Working is the New Reality Although remote working has been steadily increasing for a number of years, the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting lockdowns brought about a paradigm shift in our workings, and has led to several long-term changes in our lives. What began as a localised viral outbreak, quickly culminated into the largest remote working exercise in history, with a dramatic increase in the number of remote workers across the globe. The unprecedented event drove enterprises to quickly transition to the remote working model in order to ensure business continuity. Fortunately, remote working has provided companies with the flexibility and connection required to stay on top amidst such challenging times. Remote working or teleworking comes with several challenges, both from a human and a technology perspective. It demands meticulous business planning, change in mindset, and more than anything else, the right technology tools to make it a success. Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), which facilitates web conferencing, chat, and mobile collaboration, is central to ensuring effective remote working experience. With the right tools at hand, the challenges of remote working can be easily addressed to make it a win-win proposition for both the employees and the employer. -

Conferencing & Secure Instant Messaging

WEB CONFERENCING & SECURE INSTANT MESSAGING Conduct robust, low-cost Web meetings with Live Meeting & improve communication with Secure IM—both from Microsoft Overview Web Conferencing—utilizing Microsoft Live Meeting and Office Communications Server (OCS) 2007— enables you to conduct unlimited, real-time Web meetings with your customers. Live Meeting integrates seamlessly with Microsoft Outlook, enabling you to schedule Web meetings quickly and easily. In addition, we offer fully-integrated, Secure Instant Messaging (IM), as well as 24/7, U.S.- based, live customer service if you need assistance. While conducting a meeting you can give a presentation or demo, share your desktop, brainstorm, collaborate using whiteboards, and discuss business deals—from any Internet-connected PC. Plus, you can save time and money by avoiding the unnecessary hassle of travel. Web Conferencing Quickly and easily organize meetings around the world and save money via the following features and benefits: Features at a glance • Conduct meetings from your desk: Save time by hosting meetings online, and avoid the costs of • Conduct unlimited Web meetings for one business travel. low, monthly cost • Improve productivity: Avoid time spent traveling to and from meetings. You can also meet more • Reduce travel and long-distance telephone frequently with little to no downtime. expenses across the board • Reduce costs: Web Conferencing delivers a significant return on your investment vs. the cost of • Encourage team collaboration by traditional face-to-face meetings. conducting meetings using interactive • Keep your audience focused: Utilize dynamic communication tools in your presentations including audio and video video, chat, slides, and feedback tools. • Seamlessly integrate with your Microsoft • Record/reuse to get the most from meetings: Meetings/training events can be recorded and desktop applications, so you can schedule stored. -

Web Conferencing Services

TATA TELE BUSINESS SERVICES Web Conferencing Services Web conferencing is one of the strongest emerging mediums of communication helping organizations to expand their reach, to exchange better quality of information, and for speedier decision-making while reducing travel and time resource costs. Our Web Conferencing Service offers businesses an effortless solution for live meetings, conferencing, presentations and training via the internet particularly on TCP/IP connections. You can connect to your conference either by telephone or using your computer's speakers and microphone through a VoIP connection and build a collaboration on the go. MARKETING SOLUTIONS TATA TELE BUSINESS SERVICES BUSINESS • Cost-effective collaboration across geographies ADVANTAGES • An ideal tool for the new-age virtual commuter • Expand your reach to multiple offices • Improve productivity by saving time on commuting and gathering • Connect globally • Expand your reach with TTBS Web Conference Service Webinar • Work faster with convenient one-click access FEATURES • Enjoy a dedicated meeting room • Eliminate the hassle of software downloads for your guests • Connect to audio however you want • Manage audio meetings with your visual desktop audio controls or mobile devices • Share your screen with crystal clear quality • Personalise meetings with HD quality (H.264) webcam video for everyone • Recording meetings with one click. Send meeting record link to guests. • Stay engaged while on-the-go, easily transfer an ongoing meeting from your computer to a mobile device • Store and organise meeting files and folders in your personal cloud based file library. Share files in meetings. Transfer files or email file’s links to guests, even during meetings • Meeting reports are automatically stored in your File Library when a meeting ends. -

1 Blended Learning: a New Hybrid Teaching

ISSN: 2456-8104 JRSP-ELT, Issue 13, Vol. 3, 2019, www.jrspelt.com Blended Learning: A New Hybrid Teaching Methodology Prof. V. Chandra Sekhar Rao ([email protected] ) Professor of English, Sagar Group of Institutions, Hyderabad, India ______________________________________________________________________________ Abstract 1 Blended Learning is an approach that provides innovative educational solutions through an effective mix of traditional classroom teaching with mobile learning and online activities for teachers, trainers and students. The concept of blended learning is rooted in the idea that learning is not just a one-time event—learning is a continuous process. Blending provides various benefits over using any single learning delivery medium alone- Singh (2003). According to Friesen and Norm (2012), Blended learning is a formal education program in which a student learns at least in part through delivery of content and instruction via digital and online media with some element of student control over time, place, path, or pace. Keywords: Blended Learning, Educational Technology, Teaching Methodology Introduction In the teaching/learning process, Educators are persistently striving to discover latest and innovative methods or approaches to their students. In this process Blended Learning is one of the newest concepts being adopted. Currently, the educational system, which is in a position to meet the challenges of expansion and for catering the needs of individuals, is trying to adopt new technologies and exploring new paths to reach the goal of quality educational opportunities for all. The term, Blended Learning is increasingly used to describe the way e-learning, combining with traditional classroom methods and independent study to create a new, hybrid teaching methodology. -

Blended Learning for Sustainable Education: Moodle-Based English for Specific Purposes Teaching at Kryvyi Rih National University

E3S Web of Conferences 166, 10006 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016610006 ICSF 2020 Blended learning for sustainable education: Moodle-based English for Specific Purposes teaching at Kryvyi Rih National University Nadiya Holiver, Tetiana Kurbatova*, and Iryna Bondar Kryvyi Rih National University, 11 Vitalii Matusevych Str., Kryvyi Rih, 50027, Ukraine Abstract. The article deals with the experience of implementing Information Communication Technologies (ICT) into ESP (English for Specific Purposes) teaching and learning. Informatization and application of innovations in education has resulted in emergence of e-learning. While Moodle is one of the most popular Learning Management Systems (LMS) and it enables and facilitates the shift to the student-centered education, the article highlights its implementation and adjustment to the specific nature of teaching and learning languages for specific purposes at Kryvyi Rih National University. The article touches upon reasons for applying Moodle to language teaching/learning and its advantages as a complement to the traditional face-to-face, or classroom, mode, thus combining them into what is referred to as blended learning, or b-learning. Both the teachers and learners interviewed demonstrated positive attitudes to using the platform in their practices. Besides, the article touches upon Moodle-based opportunities of managing the content and monitoring students’ activities both in general and by individual courses. As Moodle is a web-based distance education platform not initially developed for language learning, the article invites discussion on advantages and disadvantages of its application to teaching/learning foreign languages and finding out which factors may allow language teachers and learners to boost its use and reach the set goals. -

Readytalk Web Conferencing

ReadyTalk Web Conferencing WEB CONFERENCING Meet with Confidence ReadyTalk lets you meet with confidence with a web conferencing service that is simple and intuitive, highly reliable and makes it easy to host or join a meeting. Concentrate on the substance of your meeting or webinar, not on the technology. Conferencing that Includes Everything ReadyTalk’s tools are designed so that meetings, sales demos, training sessions and webinars are easy to schedule and conduct. Unlike other web conferencing services, ReadyTalk doesn’t make you pick-and-choose features or the way you use them: • Need real-time collaboration? Hold an on-demand conference and take advantage of application and desktop sharing. Creative Ways to Use Web Conferencing • Hosting a high-profile webinar? Schedule a conference and create a branded experience with custom invitations, − Generate leads with marketing registration pages and more. webinars • Want to leverage recorded content? Use ReadyTalk’s embeddable media player, automated podcasting and built-in − Communicate with employees, social media promotion tools. customers or partners − Collaborate online with co-workers Regardless of how you use ReadyTalk’s web conferencing services, you have access to a full-featured tool set. No need to upgrade or − Host a sales demo with a prospect change packages; you get it all at one affordable price. − Conduct online training Conferencing for Everyone − Provide remote support A common complaint about web conferences is the hassle many − Enhance your website with recorded people experience when they try to join a conference. A hefty content download, the wrong version of Java or an unsupported platform or browser can frustrate participants or even make them abandon the process altogether. -

Concept Note Blended Mode of Teaching and Learning

Blended Mode of Teaching and Learning: Concept Note University Grants Commission New Delhi Index Chapters Page No 1. Background 1 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Need for Flexibility to Students / Student Centricity 2. Blended Learning: Theoretical Background 4 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Role of Teachers in BL Environment 2.3 Role of Learners in BL Environment 2.4 BL Structures in Education 2.5 Scenarios in BL 3. ICT Tools & Initiatives 12 3.1 OER : NMEICT, NPTEL, ePG, NDL 3.2 Swayam, MOOCs as Resources 3.3 Platforms: Learning and Evaluation: LMS 3.4 Other Innovative Initiatives 3.5 ICT Tools for Collaboration and User-generated content 4. Implementation of BL 18 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Pedagogies for F2F and Online Mode 4.3 Project-based Learning and Project Management platforms 4.4 Technology Infrastructure for Implementation 5. Assessment and Evaluation 26 5.1 Continuous Comprehensive Evaluation 5.2 Innovative trends in Evaluation and Assessment 6. Suggested Framework for BL 29 6.1 Background 6.2 BL Learning Environments 6.3 IPSIT: Indian Framework for BL 6.4 Essential Technology and Resources for IPSIT 6.5 Essential Pedagogy for IPSIT 6.6 Conclusion References 43 Appendix A 44 List of Online Study Material/Resources in Open Access Appendix B Template for Detailed Course Planning in Blended Learning Mode 46 Chapter I Background 1.1 Introduction It is an instructional methodology, a teaching and learning approach that combines face- to-face classroom methods with computer mediated activities to deliver instruction. This pedagogical approach means a mixture of face-to-face and online activities and the integration of synchronous and asynchronous learning tools, thus providing an optimal possibility for the arrangement of effective learning processes. -

E-Learning Objects in the Cloud: SCORM Compliance, Creation and Deployment Options

Knowledge Management & E-Learning, Vol.9, No.4. Dec 2017 e-Learning objects in the cloud: SCORM compliance, creation and deployment options Stephanie Day Emre Erturk Eastern Institute of Technology, Napier, New Zealand Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal (KM&EL) ISSN 2073-7904 Recommended citation: Day, S., & Erturk, E. (2017). e-Learning objects in the cloud: SCORM compliance, creation and deployment options. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 9(4), 449–467. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 9(4), 449–467 e-Learning objects in the cloud: SCORM compliance, creation and deployment options Stephanie Day School of Computing Eastern Institute of Technology, Napier, New Zealand E-mail: [email protected] Emre Erturk* School of Computing Eastern Institute of Technology, Napier, New Zealand E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract: In the field of education, cloud computing is changing the way learning is delivered and experienced, by providing software, storage, teaching resources, artefacts, and knowledge that can be shared by educators on a global scale. In this paper, the first objective is to understand the general trends in educational use of the cloud, particularly the provision of large scale education opportunities, use of open and free services, and interoperability of learning objects. A review of current literature reveals the opportunities and issues around managing learning and teaching related knowledge in the cloud. The educational use of the cloud will continue to grow as the services, pedagogies, personalization, and standardization of learning are refined and adopted. Secondly, the paper presents an example of how the cloud can support learning opportunities using SCORM interoperable learning objects. -

Building a Virtual Learning Environment to Foster Blended Learning Experiences in an Institute of Application in Brazil

Open Praxis, vol. 9 issue 1, January–March 2017, pp. 109–120 (ISSN 2304-070X) Building a Virtual Learning Environment to Foster Blended Learning Experiences in an Institute of Application in Brazil Andrea da Silva Marques Ribeiro , Esequiel Rodrigues Oliveira & Rodrigo Fortes Mello Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - State University of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) [email protected], [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract Blended learning, the combination of face-to-face teaching with a virtual learning environment (VLE), is the theme of this study that aims at describing and analyzing the implementation of a VLE in the Institute of Application Fernando Rodrigues da Silveira, an academic unit of the State University of Rio de Janeiro. This study’s main contribution is to reflect on the complexity of the institute that comprises schooling for basic education students and teacher education, from elementary school to postgraduate education. The wide scope of the institute encompasses face-to-face and non-presential activities, in different proportions, depending on the educational segment. Thus, starting from the assumption that blended learning teaching processes foment more student-centered educational models and facilitate interactions between individuals, a collaborative way was chosen as the VLE development method, contributing to pedagogical practices that favor meaningful learning. The VLE design was developed to meet the different needs and demands of the different educational segments. Currently there are 295 registered users. However, there are no registered basic education students so far. This can be justified by the fact that the VLE is relatively new to the community, and the participation of basic education students in the VLE depends on their teachers’ enrolment and use of the VLE itself. -

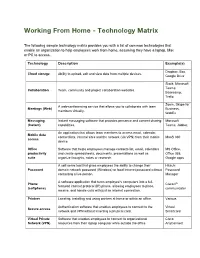

Technology Matrix

Working From Home - Technology Matrix The following sample technology matrix provides you with a list of common technologies that enable an organization to help employees work from home, assuming they have a laptop, Mac or PC to access. Technology Description Example(s) Dropbox, Box, Cloud storage Ability to upload, edit and view data from multiple devices. Google Drive Slack, Microsoft Teams, Collaboration Team, community and project collaboration websites. Basecamp, Trello Zoom, Skype for A web-conferencing service that allows you to collaborate with team Meetings (Web) Business, members virtually. WebEx Messaging Instant messaging software that provides presence and content sharing Microsoft (Instant) capabilities. Teams, Jabber, An application that allows team members to access email, calendar, Mobile data contact lists, internal sites and the network (via VPN) from their mobile MaaS 360 access device. Office Software that helps employees manage contacts list, email, calendars MS Office, productivity and create spreadsheets, documents, presentations as well as Office 365, suite organize thoughts, notes or research. Google apps A self-serve tool that gives employees the ability to change their Hitachi Password domain network password (Windows) or local intranet password without Password contacting a live person. Manager A software application that turns employee’s computers into a full- Phone Cisco IP featured internet protocol (IP) phone, allowing employees to place, (softphone) communicator receive, and handle calls with just an internet connection. Printers Locating, installing and using printers at home or within an office. Various Authentication software that enables employees to connect to the Virtual Secure access network and VPN without inserting a physical card.