Proceedings of the Global Conference on Education and Research: Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Boat

Beyond the Boat RIVER CRUISE EXTENSION TOURS Welcome! We know the gift of travel is a valuable experience that connects people and places in many special ways. When tourism closed its doors during the difficult months of the COVID-19 outbreak, Germany ranked as the second safest country in the world by the London Deep Knowled- ge Group, furthering its trust as a destination. When you are ready to explore, river cruises continue to be a great way of traveling around Germany and this handy brochure provides tour ideas for those looking to venture beyond the boat or plan a stand-alone dream trip to Bavaria. The special tips inside capture the spirit of Bavaria – traditio- nally different and full of surprises. Safe travel planning! bavaria.by/rivercruise facebook.com/visitbavaria instagram.com/bayern Post your Bavarian experiences at #visitbavaria. Feel free to contact our US-based Bavaria expert Diana Gonzalez: [email protected] TIP: Stay up to date with our trade newsletter. Register at: bavaria.by/newsletter Publisher: Photos: p. 1: istock – bkindler | p. 2: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Krautbauer | p. 3: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, fotolia – BAYERN TOURISMUS herculaneum79 | p. 4/5: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 6: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 7: BayTM – Peter von Felbert, Gert Kraut- Marketing GmbH bauer (2), Gregor Lengler, Florian Trykowski (2), Burg Rabenstein | p. 8: BayTM – Gert Krautbauer | p. 9: FC Bayern München, Arabellastr. 17 Burg Rabenstein, fotolia – atira | p. 10: BayTM – Peter von Felbert | p. 11: Käthe Wohlfahrt | p. 12: BayTM – Jan Greune, Gert Kraut- 81925 Munich, Germany bauer | p. -

The Felix Archive

KEEP THE CAT FREE Founded 1949 [email protected] Felixonline.co.uk THE 2021 FELIX SEX Fill it SURVEY IS NOW OPEN out here FelixISSUE 1772 FRIDAY 21ST MAY 2021 Union Council vote not to condemn Shell exhibit COUNCIL VOTES NOT TO CONDEMN SHELL SCIENCE MUSEUM GREENWASHING By Calum Drysdale FELIX EXCLUSIVE EUROVISION he Union Council voted last week against rais- ing even the mildest objection to the funding Meritocracy is a myth - of an exhibition on carbon capture technolo- 2021 gy at the Science Museum by Shell, the fossil Engineering department VIEWING GUIDE fuel giant. T Calum Drysdale Editor in Chief The Council voted last Tuesday by a margin of 48 to 21 with 31 abstentions against a paper proposed by he Engineering Department has issued a course on DON’T MISS Ansh Bhatnagar, a physics masters student and long Tmicroagressions that it says is recommended to all term campaigner for Imperial to divest from fossil fuel staff and students. The course is 15 minutes long and OUR 6 PAGE investment. The paper would have required the sabbat- covers what microaggressions and microaffirmations PULLOUT WITH ical officers, students taking a year out of their studies to are as well as giving examples of harmful behaviours. work in paid leadership positions in the Union, to write The course was reported on in The Telegraph which ALL THE ACTS, A a letter to the Science Museum “Expressing the urgency described it as “a list of phrases to avoid on campus”. of the climate crisisand the need for all of us to step up The Telegraph also quoted Toby Young, the general sec- SWEEPSTAKE AND and take action” as well as “Expressing the Union’s dis- retary of the Free Speech Union, who said that “protec- approval of Shell’s sponsorship of this exhibition”. -

CCD 1932 Yearbook

the 1932 griffin the 1932 griffin Pharmacy Coll ege Seniors B.S.; Ph. c. A RO :-lSO)\, DOROTHY Mich. L.c. P hi Delta Clli , Presid ent (3 ); Vice S igma Theta D elta (1 , 2, 3), F ina n Pr ~ s id e llt A llI erica n Pharmaceutical c ial Secretary ( 3 ) ; H ome Room c\sso.: ia tion (3); Coll eg ian (2); Club (2, 3); Treasurer Jun ior II Chairn,an Scnior Banqu et Entert a in C la 55 (3). llI ent Committee (3) . :\L13IOX, E\'EL \' N AGR.\ )\ OFF, CARL B.S. A .B.; Mich. L.C. Edmunds \~ r h ya r d \ Visni e\\"S ki AXDERSO:'-1, LOHRATXE A .B. A LLE)\, IID[A F. C lass Officers Junior Counci l ( 3) ; R epr esentative B.S. -in I-IolTle Ecoll olTli cs Alphaus C. Edmunds ..... .. .. ... ..... ... · ... PresideJlt of the Y. \\T . C. A. I nter·collegiate Marcus Schwartz .. .. .. ... .... .. .. .... ... V ic e-Presidellt Freshman Commission (1); A. \V . S. Coullcil ( ~1 ); Treasure r Y . \ V. C. A . Cabinet ( 3); Home Economics Cluh, ( .1); ~rodc l Leag l1 e of Xations As Ruth \iVhyard .. ..... ...... .. ..... ... .... S ecretan Treasurer (3), President (4 ) . sembl y, ParliameJlta ri a n (-4) . Clarence \Visni ewski ... .. .... .. .. .. ....... ... Treasure'r C lass C ommittees Marcus Schwartz . .... .. .. .. ... .... .. ....... .. .. .. .. Lill), Trip Morris Kroll . ....... ..... ... ... ... .. ..... ........ .... .. Baseball John Shuk... it. .......... ... ....... .... ... .. ··· · . · · ··. · ···· · · Baslletball vVilliam Briggs . .. .... .. .. .. .. ........ ..... ......... Const itHtioll \Valter Lemanski . .. .. .... ... ... .... .. ........ Sprill,Q Dall ce APTEK.-\R, D AVID D. F. S. Cooper .... .. .... .. ... ... ........ ..... ····· ···· Social CiinirlTlan .-\RXDT, GHAXT F. B.S.; M ich. L.C. A .B . in B ll s. A dlllillistration H E largest entering cl ass in the history of the Coll ege of P harmacy en Highland Park Jl1nior Coll ege; U ni H oll y, lIichi gan. -

Monitor 5. Maí 2011

MONITORBLAÐIÐ 18. TBL 2. ÁRG. FIMMTUDAGUR 5. MAÍ 2011 MORGUNBLAÐIÐ | mbl.is FRÍTT EINTAK TÓNLIST, KVIKMYNDIR, SJÓNVARP, LEIKHÚS, LISTIR, ÍÞRÓTTIR, MATUR OG ALLT ANNAÐ SIA.IS ICE 54848 05/11 ÍSLENSKA GÓÐIR FARÞEGAR! ÞAÐ ER DJ-INN SEM TALAR VINSAMLEGAST SPENNIÐ SÆTISÓLARNAR OG SETJIÐ Á YKKUR HEYRNARTÓLIN. FJÖRIÐ LIGGUR Í LOFTINU! Icelandair er stolt af því að Margeir Ingólfsson, Hluti af þessu samstarfi er sú nýjung að DJ Margeir, hefur gengið til liðs við félagið heimsfrumflytja í háloftunum nýjan tónlistardisk og velur alla tónlist sem leikin er um borð. Gus Gus, Arabian Horse sem fer í almenna Sérstök áhersla verður lögð á íslenska tónlist sölu þann 23. maí næstkomandi – en þá hafa og þá listamenn sem koma fram á Iceland viðskiptavinir Icelandair haft tæpa tvo mánuði Airwaves hátíðinni. til að njóta hans – fyrstir allra. FIMMTUDAGUR 5. MAÍ 2011 Monitor 3 fyrst&fremst Monitor Ber Einar Bárðarson ábyrgð á þessu? mælir með FYRIR VERSLUNARMANNAHELGINA Margir bíða æsispenntir eftir Þjóðhátíð í Eyjum og margir hafa nú þegar bókað far þangað. Nú gefst landanum gott tæki- færi til að tryggja sér miða á hátíðina á góðu verði því forsala miða hefst á vefsíðu N1 föstudaginn 6. maí og fá korthafar N1 miðann fjögur þúsund krónum ódýrari. FYRIR MALLAKÚTINN SÓMI ÍSLANDS, Hádegishlaðborð VOX er eitt það allra besta í bransanum. SVERÐ ÞESS OG... SKJÖLDUR! Frábært úrval af heitum og köldum réttum ásamt dýrindis eftirréttum og einstaklega Dimmiterað með stæl góðu sushi. Það kostar Nemendur FSU 3.150 krónur á fögnuðu væntanlegum Í STRÖNGU VATNI ER hlaðborðið svo skólalokum á dögunum með því að dimmit- STUTT TIL BOTNS maður fer kannski ekki þangað á hverjum degi en svo era. -

2021 Country Profiles

Eurovision Obsession Presents: ESC 2021 Country Profiles Albania Competing Broadcaster: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSh) Debut: 2004 Best Finish: 4th place (2012) Number of Entries: 17 Worst Finish: 17th place (2008, 2009, 2015) A Brief History: Albania has had moderate success in the Contest, qualifying for the Final more often than not, but ultimately not placing well. Albania achieved its highest ever placing, 4th, in Baku with Suus . Song Title: Karma Performing Artist: Anxhela Peristeri Composer(s): Kledi Bahiti Lyricist(s): Olti Curri About the Performing Artist: Peristeri's music career started in 2001 after her participation in Miss Albania . She is no stranger to competition, winning the celebrity singing competition Your Face Sounds Familiar and often placed well at Kënga Magjike (Magic Song) including a win in 2017. Semi-Final 2, Running Order 11 Grand Final Running Order 02 Australia Competing Broadcaster: Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Debut: 2015 Best Finish: 2nd place (2016) Number of Entries: 6 Worst Finish: 20th place (2018) A Brief History: Australia made its debut in 2015 as a special guest marking the Contest's 60th Anniversary and over 30 years of SBS broadcasting ESC. It has since been one of the most successful countries, qualifying each year and earning four Top Ten finishes. Song Title: Technicolour Performing Artist: Montaigne [Jess Cerro] Composer(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer Lyricist(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer About the Performing Artist: Montaigne has built a reputation across her native Australia as a stunning performer, unique songwriter, and musical experimenter. She has released three albums to critical and commercial success; she performs across Australia at various music and art festivals. -

Feel the Passion

FEEL THE PASSION LIGHTING INNOVATION FOR EVERY DRIVER, EVERY DAY CATALOGUE 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4/5 WHAT’S INSIDE 78/105 WORK LIGHTS 82 | SIBERIA RED PANDA 6/7 FUNCTION WARRANTY 80–81, 83 | SIBERIA RED TIGER 84–87 | UNITY 89 | SIBERIA RIGHT VIEW 8/9 ABOUT STRANDS 90 | SIBERIA QUBE LIGHT 91 | SIBERIA SCENE LIGHT 92–93 | 9085-SERIES 10/19 DARK KNIGHT 94–97 | ROCK SOLID 12–13 | NUUK BLACK 14–15 | IZE LED 16–17 | VIKING 106/137 WARNING LIGHTS 18–19 | SLIM 108–113 | SIBERIA NIGHT GUARD 114–117 | MONITUM 120–121 | AMBRA 22/191 SIBERIA 128 | ULTRA SLIM LIGHTHEADS 22–27 | NIGHT RANGER / BUSH RANGER 136–137 | MOUNTING ACCESSORIES 50–53 | LED BAR CURVED SRC / DRC 54–57 | LED BAR SR / DR 82 | RED PANDA 138/159 TAIL LIGHTS 83 | RED TIGER 140–143 | IZE LED 89 | RIGHT VIEW 144–145 | IZE LED CLASSIC 90 | QUBE LIGHT 148 | RED EYE 91 | SCENE LIGHT 108–113 | NIGHT GUARD 160/185 SIDE MARKERS/ 190–191 | THE SIBERIA LOOK POSITION LIGHTS 20/47 DRIVING LIGHTS 162–163 | KZ 164–165 | 810020-SERIES 22–27 | SIBERIA NIGHT RANGER / BUSH RANGER 166–167 | VIKING 28–31 | AMBASSADOR 168–169 | SLIM 32–33 | AMBASSADOR LIMITED EDITION 34–35 | FRITSLA 37 | HUDSON / YUKON 175 INTERIOR LIGHTS 38–39 | ALASKA 41 | DELTA 186/187 LICENCE PLATE LIGHTS 48/71 LED BARS 188 LED LIGHT BULBS 50–53 | SIBERIA CURVED SRC / DRC 54–57 | SIBERIA SR / DR 58–59 | NUUK DIAMOND 189 REFLECTORS 60 | NUUK BLACK 64–67 | ARCUM 68–69 | SIDE SHOOTER 192/193 SOCIAL MEDIA 70–71 | LED BAR KITS 194/195 PASSION-WEAR 72/73 MOUNTING ACCESSORIES GUIDE 74/77 MOUNTING ACCESSORIES HIGHLIGHTS, PRODUCT WHAT’S INSIDE NEWS AND INSPIRATION CREATE YOUR OWN STYLE A completely new kind of lamp with a strong attitude. -

Cirque Dreams: Illumination by Neil Goldberg, Jill Winters & David Scott

Young Critics Reviews Fall 2010-2011 Cirque Dreams: Illumination By Neil Goldberg, Jill Winters & David Scott At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 17 By Aaron Bell ILLUMINATION SHOWS ITS BRILLIANCE The house lights go down in the historic Hippodrome Theatre. We’re brought into a fast-paced newscast program when we hear the superbly resonant voice of Onyie Nwachukwu, who plays the Reporter. She tells us that another regular day has just begun, and that the daily occurrences in the “Cirque Dreams: Illumination” world will soon be lighting up the stage. Although a tad disturbed by her slightly nasal, high-belting, soulful vocals, one comes to appreciate Nwachukwu’s stylized singing; it completely fits her fun-loving, scoop-seeking reporter essence. One can’t help but appreciate her wonderful articulation and vocal clarity when she serenades us with a fabulously written opening number. This song, “Change,” gives us the main idea of the entire show, “If you don’t like it, change your mind. ” One’s mind is indeed changed by this sparkly production. The many feats of physical excellence and theatrical genius suggest how everyday life would look with an incredibly heightened sense of imagination. Santiago Rojo’s costume design and Betsy Herst’s production design bring that concept to life with their explosively colorful and symbolic wardrobes and sets. One sees cast members dressed as animated street cones, traffic lights and construction items. The set uses neon effects to brighten up the town atmosphere. The characters’ relationships with each other and their environment are interesting elements as well. -

Tikros Ir Nenusisekusios Beatos Molytės Meilės

J/b savitaRna MAISTAS Irmanto Sidarevičiaus ir Sauliaus Venckaus nuotr. Liudmila Petkevičiūtė ir VISKAS Iš Kopūstų pyragus, ir duoną kepasi pati Raudonųjų kopūstų sriuba Jums reikės: “Respublikos” leidinys Nr.18 (855) 2011 m. gegužės 7 d. ● 1 ir 1/2 l mėsos ir daržovių sultinio, ● 150 ml raudonojo vyno, ● 150 g citrinų, ● 1/2 kg raudonųjų kopūstų, TRUPMENOS ● 300 g nuluptų bulvių, ● 80 g svogūnų, LIETUVOS sėkMės RAKTAS ● 40 g riebalų, PAGAL NUMEROLogę ● 20 g miltų, auliaus Venckaus nuotr. auliaus S ● druskos, pipirų. Numerologinį kubą išradu- Citrinas nuplaukite, nuplikykite ver- si matematikė Galina šmidt dančiu vandeniu, nulupkite ir supjausty- apskaičiavo, koks yra Lietuvos kite griežinėliais. Kopūstą supjaustykite skaičiukas, kokios verslo sritys mažais kubeliais, išpjovusi šerdį ir lapų būtų pelningos mūsų šaliai, kurie sustorėjimus, užpilkite ant jo dalį sultinio politikos veikėjai čia turi perspek- ir išvirkite. Kai kopūstas išvirs, pašlaksty- tyvų, o kurie - ne. kite citrinų sultimis. Bulves supjaustykite kubeliais, užpilkite likusiu sultiniu, išvirki- 2 te ir sudėkite į kopūstų sriubą. Svogūnus supjaustykite kubeliais, pakepinkite, su- ISTORIJA dėkite miltus, truputį pakepkite ir įmai- šykite į sriubą, užvirkite, sudėkite citrinas CŽV sukūrė BIN Ladeną ir pagardinkite pagal skonį. IR PATI jį NUŽudė Kopūstų ir ryžių troškinys Jums reikės: ● garbanotojo kopūsto galvutės, ● 1 morkos, 1 ryšelio petražolių, ● 600-700 g mėsos faršo, ● 100 g ryžių, ● 50 g lašinių, ● 2 kiaušinių, ● 1-2 šaukštų miltų, KAS PER "PADARAS" TAS RAUGAS? Dešimt metų nesėkmingai ● 2 svogūnų, medžiotas garsiausias pasaulio ● 200 g grietinės, ● pipirų, mairūnų, paprikos, rozmarinų, druskos, ašytoja Liudmila PETKEVIČIŪTĖ paprastai aplenkia teroristas nužudytas. Amerikiečiai ● 50 g tarkuoto sūrio. maisto prekių parduotuves, daržovių užsiaugina gegužės 1-osios naktį 12-metės dukros akivaizdoje sušaudė O.bin Kopūstą nuplaukite ir supjaustykite sode. -

Eurovisie Top1000

Eurovisie 2017 Statistieken 0 x Afrikaans (0%) 4 x Easylistening (0.4%) 0 x Soul (0%) 0 x Aziatisch (0%) 0 x Electronisch (0%) 3 x Rock (0.3%) 0 x Avantgarde (0%) 2 x Folk (0.2%) 0 x Tunes (0%) 0 x Blues (0%) 0 x Hiphop (0%) 0 x Ballroom (0%) 0 x Caribisch (0%) 0 x Jazz (0%) 0 x Religieus (0%) 0 x Comedie (0%) 5 x Latin (0.5%) 0 x Gelegenheid (0%) 1 x Country (0.1%) 985 x Pop (98.5%) 0 x Klassiek (0%) © Edward Pieper - Eurovisie Top 1000 van 2017 - http://www.top10000.nl 1 Waterloo 1974 Pop ABBA Engels Sweden 2 Euphoria 2012 Pop Loreen Engels Sweden 3 Poupee De Cire, Poupee De Son 1965 Pop France Gall Frans Luxembourg 4 Calm After The Storm 2014 Country The Common Linnets Engels The Netherlands 5 J'aime La Vie 1986 Pop Sandra Kim Frans Belgium 6 Birds 2013 Rock Anouk Engels The Netherlands 7 Hold Me Now 1987 Pop Johnny Logan Engels Ireland 8 Making Your Mind Up 1981 Pop Bucks Fizz Engels United Kingdom 9 Fairytale (Norway) 2009 Pop Alexander Rybak Engels Norway 10 Ein Bisschen Frieden 1982 Pop Nicole Duits Germany 11 Save Your Kisses For Me 1976 Pop Brotherhood Of Man Engels United Kingdom 12 Vrede 1993 Pop Ruth Jacott Nederlands The Netherlands 13 Puppet On A String 1967 Pop Sandie Shaw Engels United Kingdom 14 Apres toi 1972 Pop Vicky Leandros Frans Luxembourg 15 Power To All Our Friends 1973 Pop Cliff Richard Engels United Kingdom 16 Als het om de liefde gaat 1972 Pop Sandra & Andres Nederlands The Netherlands 17 Eres Tu 1973 Latin Mocedades Spaans Spain 18 Love Shine A Light 1997 Pop Katrina & The Waves Engels United Kingdom 19 Only -

The Football Tourist

The Football Tourist by Stuart Fuller www.ockleybooks.co.uk To the real CMF, twenty-years of great memories....some even featuring both of us. The Football Tourist Contents Page Number Introduction ix Foreword xiii The Cast xvii Chapter One: Welcome to Spakenburg 1 Chapter Two: Stockholm Syndrome 16 Chapter Three: A New Way of Life 26 Chapter Four: A Trip to Pleasure Island 41 Chapter Five: The Seven Deadly Sins 52 Chapter Six: French Resistance 62 Chapter Seven: A Scholar and a Gent 74 Chapter Eight: Bailing out the Euro Zone 86 Chapter Nine: Sex, Drugs and 80p Beer 99 Chapter Ten: On a (Swiss) Roll 112 Chapter Eleven: Red Hot and Chilly 123 Chapter Twelve: Roman Holiday 135 Chapter Thirteen: Slav to the Rhythm 147 The Football Tourist Introduction ix Chapter Fourteen: The Boys from Brazil 161 Chapter Fifteen: Yankee Doodle Dandy 177 Introduction Chapter Sixteen: Good Old Uncle Velbert 190 Chapter Seventeen: How Many Balloons Go By? 203 Chapter Eighteen: Push the Bloody Button! 214 Chapter Nineteen: Silent Night 231 Chapter Twenty: Dundee Derby Day Delight 243 Acknowledgements 256 Tourist: [too-r-ist] noun - A person who travels to and stays in places outside their usual environment for leisure, business and other purposes. x The Football Tourist Introduction xi Modern football is crap. How many times have I heard that full of heroes and villains. throwaway comment in recent years? There have even been Again, modern football is crap, right? a couple of books that eulogise about times gone by and how Again, rubbish. much better the beautiful game was when we only had three TV In searching for a title for this book, David Hartrick and I channels, sand for pitches and steak ‘n’ chips with light ale on threw a number of titles around before deciding on ‘The Football the side for a pre-match meal. -

PATRIOTIC& PRESIDENTIAL HANDCRAFTED ALTITUDE ADJUSTMENT JUST ADD WATER RETAIL THERAPY Rockin’ the October Boardwalk 13

GROUP TOUR VIRGINIA 2019 VIRG NIA PATRIOTIC& PRESIDENTIAL HANDCRAFTED ALTITUDE ADJUSTMENT JUST ADD WATER RETAIL THERAPY Rockin’ The October Boardwalk 13 –16 ,2020 GOOD TIMES YOU WANT TO SHOW THEM ARE INEVITABLE AMERICA. START AT THE BEGINNING. Williamsburg, VA was ranked as a Top 10 Student Travel Destination by SYTA The past comes alive at the world’s largest living history museum, Colonial Williamsburg. Travel back in time with your group to the 18th century, and experience the dawn of America. Learn how things were made, discover what the culture was all about and feel the passion of the people who turned a colony into a country. SPECIAL SAVINGS FOR GROUPS OF 15 OR MORE. To begin planning your journey to the past, BRING YOUR GROUP TOUR TO LIFE. call 1-800-228-8878, [email protected], or visit colonialwilliamsburg.com/grouptours Hands-on experiences and uncommon access offered exclusively for groups. • TAKE TIME TO GO BACK • Plan your group’s Live the Life Adventure at VisitVirginiaBeach.com/GroupTour. © 2018 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 1/18 TIS-12650858 Rockin’ The October Boardwalk 13 –16 ,2020 GOOD TIMES YOU WANT TO SHOW THEM ARE INEVITABLE AMERICA. START AT THE BEGINNING. Williamsburg, VA was ranked as a Top 10 Student Travel Destination by SYTA The past comes alive at the world’s largest living history museum, Colonial Williamsburg. Travel back in time with your group to the 18th century, and experience the dawn of America. Learn how things were made, discover what the culture was all about and feel the passion of the people who turned a colony into a country. -

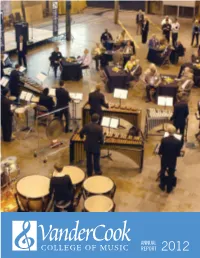

Share Your Passion

3(!2% 9/52 0!33)/. ANNUAL REPORT 2012 3(!2% 9/52 0!33)/. The New and Improved www.vandercook.edu If you have recently visited vandercook.edu, you probably noticed the school’s website has undergone a facelift. As VanderCook continues to grow, the way we connect with students, alumni, and friends will continue to expand as well. The new and improved website launched in August after much input and hours of work by our faculty, staff, and dedicated student worker, Alex Fries. The site now features upcoming events, online registra- tion, the ability to download school applications, and photos, lots of them. Scan this QR Code with your smart phone to visit vandercook.edu. VanderCook has also expanded our social media presence. Our Facebook and Twitter pages have an attentive audience and we invite you to join in on the action! Facebook: Twitter: Google+: www.facebook.com/VanderCookCollege www.twitter.com/vandercook www.gplusid.com/vandercook Table of Contents A Letter from the President .........................................................4 “A Year Through My Eyes” ....................................................... 5-8 Profile: Carlos Alban ............................................................... 9-10 A Night at the Pops ...............................................................11-12 Profile: Dr. Leah Schuman .................................................... 13-14 VanderCook and Loyola Academy .............................................15 A Letter from Ron Korbitz .........................................................16