2018 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imaging+Foto-Contact März 2010

€ 4,– • ISSN 1430 - 1121 • 39. Jahrgang • 30605 3 imaging fotfoto 201100 Fachzeitschrift für die Fotobranche • www.worldofphoto.de Die neue Lumix DMC-TZ10 Mit GPS Bilder neu erleben PMA 2010 in Anaheim — Das Sony Partner Programm Neu aufgestellt: „One Canon“ — viel besser als erwartet startet am 1. April 2010 für mehr Effizienz Positive Stimmung zeigte sich auf der PMA 2010, die vom Alle Händler, die bereit sind, das Leistungsversprechen Im Zuge der europaweiten Neuausrichtung des Vertriebes von 21. bis 23. Februar in Anaheim, Californien, stattfand. Die ame- der Marke Sony zu erfüllen, sind als Partner willkommen Canon hat sich auch die Krefelder Canon Deutschland GmbH neu rikanische Foto- und Imagingbranche rechnet für das laufende und können von den speziellen Vorteilen des Sony organisiert. Dies gewährleistet nicht nur mehr Kunden- Jahr mit einer spürbaren Nachfragesteigerung. S. 1 2 Partner Programms deutlich profitieren. S. 16 orientierung, sondern auch schnellere Entscheidungen. S. 28 Verkaufsstart für die neue Lumix DMC-TZ10 Die Reisekamera mit GPS Wie ihre Vorgängerin ist die Lumix TZ10 mit einem f3,3–4,9/25–300 mm 12fach-Zoom Leica Objektiv ausge- stattet, dessen Bildstabilisator Power- OIS jetzt noch effizienter arbeitet. Dank „Intelligent Resolution“ ergibt sich in der „Intelligent Zoom“-Funktion ein Zoomfaktor von 16fach, was einer längsten rechnerischen Brennweite von 400 mm entspricht. Die Auflösung des 1/2,33“ CCD Multi-Aspekt Bildsen- sors wurde von 10 auf 12,1 Megapixel erhöht. Durch seine spezielle Techno- logie stellt dieser Sensor sicher, dass der Bildwinkel auch bei Aufnahmen mit unterschiedlichen Seitenverhältnis- sen (zum Beispiel 4:3 und 16:9) iden- tisch und damit die vom Fotografen Panasonic bringt im März mit der neuen Lumix TZ10 die Nach- gewählte Perspektive erhalten bleibt. -

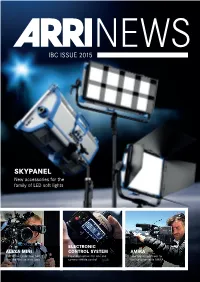

SKYPANEL New Accessories for the Family of LED Soft Lights

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2015 SKYPANEL New accessories for the family of LED soft lights ELECTRONIC ALEXA MINI CONTROL SYSTEM AMIRA Karl Walter Lindenlaub ASC, BVK Expanded options for lens and New application areas for tries the Mini on Nine Lives camera remote control the highly versatile AMIRA EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES We hope you can join postproduction through ARRI Media, illustrating us here at IBC, where we the uniquely broad range of products and services are showcasing our latest we offer. 18 camera systems and lighting technologies. For the ARRI Rental has also been busy supplying the first time in ARRI News we are also introducing our ALEXA 65 system to top DPs on major feature films newest business unit: ARRI Medical. Harnessing – many are testing the large-format camera for the core imaging technology and reliability of selected sequences and then opting to use it on ALEXA, our ARRISCOPE digital surgical microscope main unit throughout production. In April IMAX is already at work in operating theaters, delivering announced that it had chosen ALEXA 65 as the unsurpassed 3D images of surgical procedures. digital platform for 2D IMAX productions. In this issue we share news of how AMIRA is Our new SkyPanel LED soft lights, announced 12 being put to use on productions so diverse and earlier this year and shipping now as promised, are wide-ranging that it has taken even us by surprise. proving extremely popular and at IBC we are The same is true of the ALEXA Mini, which was unveiling a full selection of accessories that will introduced at NAB and has been enthusiastically make them even more flexible. -

Introduction

CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction This book consists of edited conversations between DP’s, Gaffer’s, their crew and equipment suppliers. As such it doesn’t have the same structure as a “normal” film reference book. Our aim is to promote the free exchange of ideas among fellow professionals, the cinematographer, their camera crew, manufacturer's, rental houses and related businesses. Kodak, Arri, Aaton, Panavision, Otto Nemenz, Clairmont, Optex, VFG, Schneider, Tiffen, Fuji, Panasonic, Thomson, K5600, BandPro, Lighttools, Cooke, Plus8, SLF, Atlab and Fujinon are among the companies represented. As we have grown, we have added lists for HD, AC's, Lighting, Post etc. expanding on the original professional cinematography list started in 1996. We started with one list and 70 members in 1996, we now have, In addition to the original list aimed soley at professional cameramen, lists for assistant cameramen, docco’s, indies, video and basic cinematography. These have memberships varying from around 1,200 to over 2,500 each. These pages cover the period November 1996 to November 2001. Join us and help expand the shared knowledge:- www.cinematography.net CML – The first 5 Years…………………………. Page 1 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Page 2 CINEMATOGRAPHY Mailing List the first 5 years Introduction................................................................ 1 Shooting at 25FPS in a 60Hz Environment.............. 7 Shooting at 30 FPS................................................... 17 3D Moving Stills...................................................... -

Product Guide

PRODUCT GUIDE VOLUME 12 Engineered for the eye CONTENTS ENTERTAINMENT LIGHTING 8 - 81 ARChiteCTUral Lighting 82 - 115 LED VIDEO 116 - 151 CONTROL 152 - 201 ATMOSPHERIC EFFECTS 202 - 247 ACCessories 248 - 263 ServiCE 264 - 265 Worldwide partners/indeX 266 - 270 NOTES 271 - 274 3 Introduction Martin Professional is the world’s leading dynamic lighting and visual solutions company. For over 25 years, we’ve worked in part- nership with leading designers to deliver high impact visual solu- tions for tours, special events, theatres, TV studios, nightclubs, leisure environments, and architectural and commercial settings across the globe. Our state-of-the-art luminaires and video displays are of the highest quality. Add a line of advanced media servers, lighting controllers and smoke machines and we offer the industry’s most comprehensive range of visual solutions. At Martin, we pride ourselves on the level of excellence we en- gineer into every product while aiming to reduce operating and maintenance costs. Our products consistently deliver the indus- try’s best return on investment. It is our ambition to be the greenest company in our industry. We regard environmental regulations as the minimum standards of environmental performance and are developing the most power- ful and energy-efficient LED light sources on the market. We are proud to be the lighting division of HARMAN International Industries. HARMAN (www.HARMAN.com) designs, manufac- tures and markets a wide range of audio and infotainment solu- tions for the automotive, consumer and -

Photo/Grip List

Photo/Grip List Please complete & fax to (347) 823-2309 or Email to [email protected] You will be contacted by a Production Rentals Booking Agent ASAP with a quote Job Name: Company Name: Contact Name: Contact Position: Email: Phone: Fax: Shoot Days: Pick-up Date: Return Date: PO#: Job#: Do you have a truck holding? Yes/No: Would you like it pre-loaded? Yes/No: Special Requests/Notes: Our Other New York Offerings Include... Production Supplies, Walkies, WiFi, Strobe Lighting & Grip, Camera, Digital & of course our first-class Motorhomes You Name it, we’ve got it.. Online at Quixote.com Quixote Production Rentals | 1082 Flushing Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11237 | P: 347 448 8414 | F: 347 823 2309 | www.Quixote.com Updated 7/17 Please complete & fax to (347) 823-2309 or Email to [email protected] Grip You will be contacted by a Production Supplies Booking Agent ASAP with a quote Grip Grip (cont’d) C Stand 40" Complete $10.00 Sissors Clips $10.00 C Stand 20" Complete $10.00 Cardellini Clamp 2" End Jaw $8.00 Extra C Stand Arm + Knuckle $5.00 Cardelini Clamp 3" Center Jaw $8.00 Large Rolling Base for C Stand $10.00 Duck Bills $8.00 Small Rolling Base for C Stand $10.00 Baby Wall plate (3", 6", or 9") $5.00 Reel Efx Fan w/Rolling Base $75.00 Junior Wall plate $5.00 Kit Stand $10.00 Magic Arm $8.00 Lawn Dart $10.00 Junior Offset Arms $25.00 Preemie Baby $10.00 Baby Offset Arms $20.00 Beefy Baby 3 Riser $12.00 Baby Triple Header $25.00 Low Roller $15.00 Junior Triple Header $25.00 Medium Roller $20.00 Studded C-clamp - 6" $10.00 High Roller $25.00 Studded -

Download Full EQ List

HIGHLIGHT STUDIOS ALL studio rental packages include basic grip. Extra gear added to a package is charged per item. Canon Hasselblad H EOS 1DX MKII DSLR $175.00 H5X Camera Body w/ Finder $125.00 EOS 5D Mark IV DSLR $110.00 H4X Camera Body w/ Finder $95.00 5DS DSLR $90/day $90.00 HC 35m f/3.5 Lens $65.00 EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM Zoom Lens $40.00 HC 50m f/3.5 Lens $55.00 70-200mm f/2.8L II USM Zoom Lens $40.00 HC 80m f/2.8 Lens $25.00 EF 35mm f/1.4 USM Lens $35.00 HC 100m f/2.2 Lens $65.00 EF 50mm f/1.2 L Lens $30.00 HC 120m f/4.0 Macro Lens $75.00 EF 85mm f/1.2 L II Lens $35.00 HC 150m f/3.2 Lens $65.00 100mm f/2.8 L II Macro Lens $30.00 HC 50-110m f/3.5-4.5 Lens $95.00 Speedlight 600 EX-RT $25.00 13mm Extension Tube $20.00 Phase One Nikon IQ 260 (H Mount) $600.00 D810 DSLR $150.00 AF-S Nikkor 35mm f/1.4 G Lens $35.00 AF-S Nikkor 50mm f/1.4 G Lens $20.00 Kino Flo AF-S Nikkor 58mm f/1.4 G Lens $40.00 4x4 Panel w/ Ballast $75.00 AF-S Nikkor 85mm f/1.4 G Lens $40.00 2x4 Ballast w/ Ballast $50.00 AF-S Nikkor Micro 105mm f/2.8 Lens $35.00 AF-S Nikkor 24-70mm f/2.8 Lens $35.00 Digital AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8 G Lens $45.00 Mac Pro Cylinder 3.0GHZ 64GM RAM $400.00 Speedlight SB-900 $25.00 Mac Book Pro 15” $200.00 Eizo 24” CG247 Graphics Monitor $200.00 M Wacom Intous Tablet $150.00 Profoto Photek Pro-8A 2400W Air Pack $80.00 S 36” Softlighter $10.00 Pro-B4 1000W Air Pack $85.00 M 46” Softlighter $10.00 Pro-B4 B4 Battery $50.00 L 60” Softlighter $15.00 B1 2-Head Kit $90.00 Uncles Sam Umbrella w/ grip $40.00 B1 Pro Air TTL Moonlight 500W $45.00 -

High Performance 2" Aperture (HP-2) - Recessed

JOHNSTON COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT WALLACE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL DESIGN DEVELOPMENT PRESENTATION frk architects + engineers December 12, 2016 frk architects + engineers PROJECT DESIGN TEAM WALLACE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOHNSTON COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT ARCHITECT frk architects + engineers Project Principal: Tom Wollan, AIA Project Architect: Tim Veatch, AIA MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL/STRUCTURAL ENGINEER Bluestone Engineering Mechanical Engineer: Tim Shimerdla, PE Electrical Engineer: Justin Olson, PE Structural Engineer: Ben Long, PE CIVIL ENGINEER Snyder and Associates Civil Engineer: Don Marner, PE OWNER Johnston Community School District School Board: Mark Toebben, President Marci Cordaro, Vice-President Greg Dockum Deb Henry Jill Morrill Matt Stahr Brad Ortmeier Alexis Rivett, Student Representative Nicole Hobson, Student Representative Superintendent of Schools: Corey Lunn Director of Operations : George Smith 2600 westown parkway, suite 340, west des moines, iowa 50266 : p 515.223.5100 f 515.223.7226 www.frk-ae.com frk architects + engineers ARCHITECTURAL NARRATIVE DESIGN DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL WALLACE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL JOHNSTON COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT The existing Johnston Middle School will go through an extensive adaptive reuse construction project to become the new location for Wallace Elementary School. The site will have minor changes to accommodate the elementary program. Bus drop-off and parking will move to the west end of the building. The west entrance will be a dedicated entrance for bussed students. The existing south drive will become the parent drop-off lane for the south entrance of the elementary school and the early childhood program. New outdoor playgrounds will be located on the northeast corner of the site for the elementary school. An early childhood playground will be located in the southwest corner of the site. -

Cinema Canada (416) 598-6829 Or (514) 272-5354 Cipal Photography to Be Completed Later This Lavoie Asst

• C IN E MAti • PRODUCTION GUIDE by Jamie Gaetz Michael Berry, Gilbert Shilt on, Brad Turner and others TBA sC. Rick Drew , Barry Clark , Aubr e ANNE TRISTER MAJOR H Salomon , All Harri s, Andrew Nicholls, Darrell A film about both the absence 01 love and the he following is a list of films In production (actually before cameras) Vicke rs, Pet er Jobin, DaVid Eames, John T. many form s that love may take, telling the story PRODUCTIONS and In negotiation In Canada. Needless to say, the films which are Dugan, Nancy Ann Miller, Gilbert Shi lton p. man. of a troubled young women 01 25 who lets (604) 669-4402 still in the project stage are subject to changes. A third category,ln Harold Tichenor d.o.p. Philip Lindzey art d. Jill everythi ng in her life go when her lather dies T Scott sd. Ralph Parker ward . Jane Grose key grip Based on an original idea by Lea Pool. Shooting JUST ANOTHER MISSING KID Pre-Production, will be used to indicate films which are in active pre-pro began mid -March and cont inues until May on Dave Humphreys p. coord . Mara McSweeny Started shooting May 6 in Vancouver and various locations in Quebec, Israel and SWitzer duction , having set a date for the beginning of principal photography and gaffer Barry Reid cons. coord . Garry Brolly trans surrounding areas. Will continue for 25 days being engaged in casting and crewing. Films are listed by the name of the port coord . George Grieve animal coord. Debbie land. -

Download the Sample Pages

Shoot to Thrill: A Hard-Boiled Guide to Digital Photography Associate Publisher Copyright © 2010 by Derek Pell Greg Wiegand Cover photograph by the author. Acquisitions Editor All photographs in the book are by Derek Pell, except Laura Norman where otherwise indicated. Development Editor All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, Laura Norman stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, Managing Editor without written permission from the publisher. No patent Patrick Kanouse liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information Senior Project Editor contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken in Tonya Simpson the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. Nor is any liability assumed Copy Editor for damages resulting from the use of the information contained Karen Gill herein. Indexer ISBN-13: 978-0-7897-4240-7 Ken Johnson ISBN-10: 0-7897-4240-3 Technical Editor Robyn Ness Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on fi le Publishing Coordinator Printed in the United States of America Cindy Teeters First Printing: September 2009 Trademarks All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Que Publishing cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as aff ecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Warning and Disclaimer Every eff ort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fi tness is implied. -

Bill Hurter. the Best of Professional Digital Photography. 2006

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Bill Hurter started out in photography in 1972 in Washington, DC, where he was a news photographer. He even covered the political scene—including the Watergate hearings. After graduating with a BA in literature from American University in 1972, he completed training at the Brooks Institute of Photography in 1975. Going on to work at Petersen’s PhotoGraphic magazine, he held practically every job except art director. He has been the owner of his own creative agency, shot stock, and worked assignments (including a year or so with the L.A. Dodgers). He has been directly involved in photography for the last thirty years and has seen the revolution in technology. In 1988, Bill was awarded an honorary Masters of Science degree from the Brooks Institute. He has written more than a dozen instructional books for professional photographers and is currently the editor of Rangefinder magazine. Copyright © 2006 by Bill Hurter. All rights reserved. Front cover photograph by Yervant Zanazanian. Back cover photograph by Craig Minielly. Published by: Amherst Media, Inc. P.O. Box 586 Buffalo, N.Y. 14226 Fax: 716-874-4508 www.AmherstMedia.com Publisher: Craig Alesse Senior Editor/Production Manager: Michelle Perkins Assistant Editor: Barbara A. Lynch-Johnt ISBN: 1-58428-188-X Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 2005937370 Printed in Korea. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechan- ical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise, without prior written consent from the publisher. -

Microstock Photography

Microstock Photography How to Make Money from Your Digital Images Douglas Freer AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Acquisitions Editor: Cara Anderson Developmental Editor: Valerie Geary Publishing Services Manager: George Morrison Project Manager: Kathryn Liston Editorial Assistant: Kathryn Spencer Marketing Manager: Marcel Koppes Interior and Cover Design: Alisa Andreola Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2008 Quentin Douglas Freer Bargate. Published by Elsevier Inc. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, E-mail: permissions@ elsevier.com. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier .com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Application submitted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-0-240-80896-3 For information on all Focal Press publications visit our website at www.books.elsevier.com 08 09 10 11 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China. -

MJS Rental Equipment.Numbers

On-Site Equipment/Grip Rental pricing Studio: $800/day Soft Boxes & Umbrellas Day Week Elinchrom 74" OCTA BANK w/ $55 $160 Profoto Adapter Elichrom 17"X17" reflector (Hardbox) $15 $50 with removable grid and frost Profoto 4’ strip light $10 $30 Chimera CHP2BL Pro II Soft-Box for $10 $30 Flash. 54”X72” Photoflex Multidome Q3 $9 $27 Photoflex Stripdome Q3 $9 $27 Photoflex Octodome $9 $27 Umbrellas (We have 2) $4 $12 Total Stands Grip and Misc. Day Week Sandbags, each (Free to use with full $3 $9 day rental of studio) Apple Boxes-Assorted, each: (Free $4 $12 to use with full day rental of Studio) ‘C’ Stands W/Arm-Assorted, each (5 $5 $15 included with full day rental of studio) (We have a total of 13 available) Baby Jr. Roller Triple Riser w/Arm $5 $15 (ea) (we have 3 available) Stands Grip and Misc. Day Week Regular Tall Light Stands $4 $12 Foba 10ft Camera stand (Free to use $50 $150 with 8hr rental of Studio) Calumet Rolling Boom Stand $10 $30 Photek Background Stand set $10 $30 Pocketwizard Plus III and other $10 $30 Pocketwizard Tranceivers. Matthews Auto Pole $8 $25 Apple Display 27-inch (2560 x 1440) $100 $300 Commercial Refrigerator/Freezer $6 $18 (each) (Free to use with full day rental of Studio) V-Flats (free to use) $0 $0 AC extension cords (Free to use) Total $0 Profoto Lighting Day Week ACUTE2 2400 GENERATOR (No $40 $135 built-in poketwizard) PROFOTO D4 2400R (built in $55 $165 PocketWizard) ACUTE 2/D4 HEAD W/Standard $25 $75 zoom reflector.