Perplexing Federal Cases from Mississippi: Lessons for School Administrators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Guest Artists

Guest Artists George Hamilton, Broadway and Film Actor, Broadway Actresses Charlotte D’Amboise & Jasmine Guy speaks at a Chicago Day on Broadway speak at a Chicago Day on Broadway Fashion Designer, Tommy Hilfiger, speaks at a Career Day on Broadway SAMPLE BROADWAY GUEST ARTISTS CHRISTOPHER JACKSON - HAMILTON Christopher Jackson- Hamilton – original Off Broadway and Broadway Company, Tony Award nomination; In the Heights - original Co. B'way: Orig. Co. and Simba in Disney's The Lion King. Regional: Comfortable Shoes, Beggar's Holiday. TV credits: "White Collar," "Nurse Jackie," "Gossip Girl," "Fringe," "Oz." Co-music director for the hit PBS Show "The Electric Company" ('08-'09.) Has written songs for will.i.am, Sean Kingston, LL Cool J, Mario and many others. Currently writing and composing for "Sesame Street." Solo album - In The Name of LOVE. SHELBY FINNIE – THE PROM Broadway debut! “Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert” (NBC), Radio City Christmas Spectacular (Rockette), The Prom (Alliance Theatre), Sarasota Ballet. Endless thanks to Casey, Casey, John, Meg, Mary-Mitchell, Bethany, LDC and Mom! NICKY VENDITTI – WICKED Dance Captain, Swing, Chistery U/S. After years of practice as a child melting like the Wicked Witch, Nicky is thrilled to be making his Broadway debut in Wicked. Off-Broadway: Trip of Love (Asst. Choreographer). Tours: Wicked, A Chorus Line (Paul), Contact, Swing! Love to my beautiful family and friends. BRITTANY NICHOLAS – MEAN GIRLS Brittany Nicholas is thrilled to be part of Mean Girls. Broadway: Billy Elliot (Swing). International: Billy Elliot Toronto (Swing/ Dance Captain). Tours: Billy Elliot First National (Original Cast), Matilda (Swing/Children’s Dance Captain). -

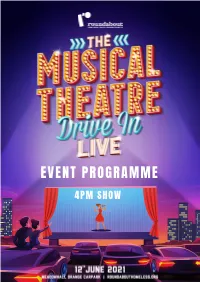

4Pm Programme

EVENT PROGRAMME 4PM SHOW Roundabout are incredibly excited to be bringing you this brand new theatrical extravaganza LIVE at Meadowhall! Bring a picnic and sit outside, sing and dance along to your favourite songs in your own safe, designated space, or enjoy from the comfort of your car! With your own personal space next to your car, this is a covid safe event. The drive-in format ensures all vehicles are safely social distanced and the numbers of performers on stage are limited to follow all current government safety guidelines. Read on to find out more about who is performing in each show, and see which fabulous musical tracks you'll hear! Thank you for coming to the event today, for supporting performers returning to the stage after a difficult year, and for supporting Roundabout. Together, we can help homeless young people in South Yorkshire have a brighter future. ABOUT THE CHARITY Roundabout is South Yorkshire’s local youth housing charity providing shelter, support and life skills to young people aged 16-25 who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. Roundabout supports over 250 young people living in accommodation every day, either provided by or supported by our charity. We have a hostel, residential projects in Sheffield, Rotherham and Doncaster and provide key services delivering comprehensive programmes of training, involvement and empowerment which help to break the cycle of homelessness and develop long term independent living skills. ON THE DAY When you arrive at Orange Car Park 3, please have your ticket ready to be scanned (either printed or displayed on your phone). -

CT Unstaged Winter 2021

Classes are Listed from Youngest Grades to Oldest Acting: Silly with Seuss - ONLINE Teacher: Billy Cooper PreK-1st Grades Mon 4:00-5:00 Would you, could you, do a jig? Would you, could you, act like a pig? The wonderful, wacky world of Dr. Suess is full of funny rhymes and hilarious characters. We’ll be using the world of Seuss stories to explore creative play, imagination, acting, speaking and working together as a group. Lots of movement and engagement for our youngest thespians! Musical Theatre: Disney’s Descendants - ONLINE Teacher: Sarah Beglen Kdg-2nd Grades Mon 5:00-6:00 Sometimes, it’s good to be a little bad! Based on a series of popular Disney movies and now a new musical, this class will use Descendants as the basis for our class. We’ll learn to really embody a character using their motivation, physicality and vocal qualities. Learn to get into the mind of a character and portray them from the inside out. Unleash your acting abilities and take your skills to the next level. We’ll also be dancing and groovin’ to some of the super fun songs. Let’s move and act! Acting: Toy Story Saga - IN-PERSON Teacher: Cyndy Soumar Kdg-2nd Grades Wed 5:00-6:00 Buzz, Woody, Jessie, Bo Peep, Slink, Rex and the gang have had TONS of exciting adventures! These lovable characters demonstrate lessons of friendship, loyalty, growing up and togetherness. We’ll use scenes, inspiration and characters from ALL of the amazing Toy Story movies to stretch our acting and character chops. -

Musical Theatre: a Forum for Political Expression

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Musical Theatre: A Forum for Political Expression Boyd Frank Richards University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Richards, Boyd Frank, "Musical Theatre: A Forum for Political Expression" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/337 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT • APPROVAL -IJO J?J /" t~.s Name: -·v~ __ ~~v~--_______________ _______________________- _ J3~~~~ ____ ~~:__ d_ epartmen. ______________________ _ College: ~ *' S' '.e..' 0 t· Faculty Mentor: __ K~---j~2..9:::.C.e.--------------------------- PROJECT TITLE; _~LCQ.(__ :Jherui:~~ ___ I1 __:lQ.C1:UiLl~-- __ _ --------JI!.c. __ Pdl~'aJ___ ~J:tZ~L~ .. -_______________ _ ---------------------------------------_.------------------ I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors level undergraduate research in this :::'ed: _._________ ._____________ , Faculty !v1entor Date: _LL_ -9fL-------- Comments (Optional): Musical Theater: A Forum for Political Expression Presented by: Ashlee Ellis Boyd Richards May 5,1999 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................2 Introduction: Musical Theatre - A Forum for Political Expression .................. -

Would Jesus Attend the Prom?

WOULD JESUS ATTEND THE PROM? he dictionary defines a prom as “a when lust hath conceived, it bringeth forth formal dance given by a high school sin: and sin, when it is finished, bringeth Tor college class.” Dancing is defined forth death” (James 1:14-15). as “to perform a rhythmic...succession of Any activity that promotes lustful or bodily movements usually to music, to sensual thoughts and actions is sinful. move quickly up and down or about.” Dancing does that. John the Baptist was What does the Bible say? Does it allow beheaded because of a rash vow made by or condemn dancing? It condemns it as Herod whose passion was aroused by sinful, not innocent. watching a dancing young maiden (Mark Lasciviousness is the Bible word 6:16-29). Dancing is not innocent! which condemns dancing as sensual and Lasciviousness and wantonness are sinful. It is defined as: “unbridled lust, condemned in Mark 7:22, 2 Cor. 12:21, excess, licentiousness, wantonness, outra- Gal. 5:19-21, Eph. 4:19, 1 Peter 4:3, Jude geousness, shamelessness, insolence, inde- 1:4, Rom. 13:13, 2 Peter 2:7,18. Those who cent bodily movements, unchaste knowingly and purposefully involve them- handling of males and females” selves in lasciviousness have no hope of (Thayer, p.79). Dancing certainly involves heaven unless they repent and stop the “indecent bodily movements” and the activity. The Lord says, “...they which do “unchaste handling of males and such things shall not inherit the kingdom females.” That is its design and appeal. of God” (Gal. -

NATASHA DAVISON AEA, SAG, AFTRA, SDC, NAMT , MTEA, the Broadway League

NATASHA DAVISON AEA, SAG, AFTRA, SDC, NAMT , MTEA, The Broadway League 3802 Agape Lane, Austin, TX 78735 E-Mail: [email protected] (512) 471-3468 Office SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS ● Musical Theatre Faculty/Choreographer/Director at The University of Texas at Austin ● Current & Founding Artistic Director of New Musical Development/Texas Musical Theatre Workshop at The University of Texas Responsible for recruiting and producing new musical theatre work to be developed ● Head of Dance/Choreographer St. Andrews School ● Diverse professional experience in performing (dancing, acting, singing), choreography, theatrical production, television production, broadcasting, writing, and directing ● Highly experienced in musical theatre as choreographer & performer, has worked both domestically and internationally ● Featured in plays, television, film, commercials, and music videos TEACHING POSITIONS MUSICAL THEATRE FACULTY/CHOREOGRAPHER/DIRECTOR University of Texas-Austin COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS FACULTY University of Texas-Austin since 2009 HEAD OF DANCE PROGRAM/CHOREOGRAPHER St. Andrews School- Austin since 2009 MASTER CLASSES/COACHING various ages and skill levels throughout the Region GUEST ARTIST University of Texas (Austin), St. Edwards University (Austin), Booker T. Washington (Dallas) St. Andrews School (Austin), Tex-Arts (Austin), Trinity School (Austin), Ashley Hall (Charleston, S.C.), St. Stephens School (Austin), The Raleigh School of Ballet (Raleigh), Ravenscroft School (Raleigh), Ballet Austin, Zach Scott Theatre (Austin), -

THE PROM - Final Broadway Draft 1

- PERUSAL PACK- Book & Lyrics by CHAD BEGUELIN Book by BOB MARTIN Music by MATTHEW SKLAR Based on an original concept by JACK VIERTEL 9/3/19 THE PROM - Final Broadway Draft 1. 1 A STEP AND REPEAT 1 It’s a “step and repeat”. Actors dressed in gowns and tuxedos pose for pictures. A few cameras flash. OLIVIA KEATING (Into camera.) It’s Olivia Keating of Broadway Mania and we’re here for the opening night of “Eleanor! - The Eleanor Roosevelt Musical”, starring the incomparable Dee Dee Allen. DEE DEE ALLEN enters, approaches OLIVIA. OLIVIA KEATING (CONT’D) (To DEE DEE.) Dee Dee, you’re a Broadway star. DEE DEE Yes I am. OLIVIA KEATING Change You have your choice of roles, what drew you to Eleanor? to DEE DEE Eleanor Roosevelt was a powerful, brave charismatic woman that no one had ever heard of. Her story needs to be told. People need to know it’s possible to change the world, whether you are a homely middle-aged first lady, or a BroadwayPerusal star. ProductionBARRY GLICKMAN enters. A SECOND SubjectREPORTER stops him. SECOND REPORTER And forhere’s Barry Glickman! You were brilliant TRWas FDR. BARRY I know. The moment I first stepped into FDR’s Notshoes, and by shoes I mean wheelchair, I had an epiphany. I realized there is no difference between the President of the United States and a celebrity. We both have power. The power to changeContent the world. DEE DEE It’s an awesome responsibility. THE PROM - Final Broadway Draft 2. BARRY Let’s talk process. -

Low Male Voice Repertoire in Contemporary Musical Theatre: a Studio and Performance Guide of Selected Songs 1996-2020

LOW MALE VOICE REPERTOIRE IN CONTEMPORARY MUSICAL THEATRE: A STUDIO AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE OF SELECTED SONGS 1996-2020 by Jeremy C. Gussin Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Ray Fellman, Research Director __________________________________________ Brian Gill, Chair __________________________________________ Jane Dutton __________________________________________ Peter Volpe December 10, 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 Jeremy Gussin iii Preface This project is intended to be a resource document for bass voices and teachers of low male voices at all levels. For the purposes of this document, I will make use of the established term low male voice (LMV) while acknowledging that there is a push for the removal of gender from voice classification in the industry out of respect for our trans, non-binary and gender fluid populations. In addition to analysis and summation of musical concepts and content found within each selection, each repertoire selection will include discussions of style, vocal technique, vocalism, and character in an effort to establish routes towards authenticity in the field of musical theatre over the last twenty five years. The explosion of online streaming and online sheet music resources over the last decade enable analysis involving original cast recordings, specific noteworthy performances, and discussions on transposition as it relates to the honoring of character and capability of an individual singer. My experiences with challenges as a young low voice (waiting for upper notes to develop, struggling with resonance strategies above a D♭4) with significant musicianship prowess left me searching for a musically challenging outlet outside of the Bel Canto aesthetic. -

Book by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin Music by Matthew Sklar • Lyrics by Chad Beguelin

Book by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin Music by Matthew Sklar • Lyrics by Chad Beguelin Based on the New Line Cinema film written by David Berenbaum DECEMBER 2019 HOPE LIVES HERE. Cancer changes everything. But at Stony Brook University Cancer Center, we’re changing everything about cancer care. By bringing doctors and researchers together like never before, we’re bringing the latest innovations in personalized cancer care close to you. With powerful technology, clinical trials, comprehensive support services, precision medicine, and expertise in your particular cancer, we’re giving new hope to those changed by cancer and to all the people who love them. ThisChangesCancerCare.com Stony Brook University/SUNY is an affirmative action, equal opportunity educator and employer. 19100658H 2 HOLIDAY 2019 GATEWAY PLAYHOUSE 3 Marketing Solutions for a Digital & Analog World SEARLES GRAPHICS est.1974 web • print • design searlesgraphics.com | 631.400.3086 4 HOLIDAY 2019 Listen to Lawrence! …and learn how to plan the RIGHT way. FREE SEMINAR! • Learn how to protect your assets from the high costs of Long Term Care • Learn how to protect the money you leave to your children from their divorce • Learn how to protect your children’s inheritance from creditors, taxes and their own poor judgment Lawrence Eric Davidow This informative program is FREE, Senior and Managing Partner DAVIDOW, DAVIDOW but reservations are required. SIEGEL & STERN, LLP Call 631-234-3030 or go online at: LONG ISLAND’S ELDER LAW, SPECIAL NEEDS www.davidowlaw.com to find an AND ESTATE PLANNING FIRM upcoming seminar in your area! DAVIDOW, DAVIDOW, SIEGEL & STERN, LLP Original Firm Founded 1913 Long Island’s Elder Law, Special Needs and Estate Planning Firm 1050 Old Nichols Road - Suite 100, Islandia, New York 11749 | Tel. -

![[Virtual] Gala 05.02.21 5:00 Pm Pst](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0803/virtual-gala-05-02-21-5-00-pm-pst-2420803.webp)

[Virtual] Gala 05.02.21 5:00 Pm Pst

LACHSA’S 4TH ANNUAL CELEBRATION GALA A special evening to benefit the LA COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE ARTS 2021 FUTURE ARTISTS [VIRTUAL] GALA 05.02.21 5:00 PM PST FOUNDATION 2021 FUTURE ARTISTS [VIRTUAL] GALA 05.02.21 5:00 PM PST This evening of celebration will support the future artists and changemakers of Los Angeles County and help keep high-quality free public arts education accessible to any student with talent and a dream FOUNDATION 2021 FUTURE ARTISTS [VIRTUAL] GALA SPECIAL APPEARANCE BY LACHSA ALUMNI HAIM Grammy-nominated rock band HAIM featuring Este, Danielle and Alana HAIM give a special performance for LACHSA! Multi-platinum recording artist, songwriter, actor & producer and LACHSA alumni Josh Groban makes a special appearance at the Future Artists [Virtual] Gala to support LACHSA! 2021 GALA CHAIR Melina Kanakaredes Melina Kanakaredes, is a multi-talented actor, writer, director and philanthropist. Her work in TV, film and Broadway has earned her critical acclaim. Ms. Kanakaredes is best known for her long running starring role of Stella Bonasera in the CBS series CSI: New York. While working full time on this series, she was inspired and supported by her colleagues to start writing. Melina sold her first penned half hour pilot script to CBS in 2004 and consequently began writing and acting simultaneously on CSI: New York. Prior to CSI: New York, Ms. Kanakaredes starred for five seasons as Dr. Sydney Hansen on the NBC-TV critically acclaimed series Providence. Other television credits include Notorious, Extant, NYPD Blue, New York News, Leaving LA, The Practice and Oz. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA PLAYBILL.COM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE Disney Theatrical Productions under the direction of Thomas Schumacher presents Music by Lyrics by Book by ALAN MENKEN HOWARD ASHMAN CHAD BEGUELIN TIMd RICE an CHAD BEGUELIN Based on the Disney film written by RON CLEMENTS, JOHN MUSKER, TED ELLIOTT & TERRY ROSSIO and directed and produced by JOHN MUSKER & RON CLEMENTS Starring ADAM JACOBS MICHAEL JAMES SCOTT COURTNEY REED ISABELLE MCCALLA JONATHAN WEIR REGGIE DE LEON JC MONTGOMERY JERALD VINCENT ZACH BENCAL PHILIPPE ARROYO MIKE LONGO KORIE LEE BLOSSEY ELLIS C. DAWSON III ADAM STEVENSON MARY ANTONINI MICHAEL BULLARD MICHAEL CALLAHAN JACE CORONADO CORNELIUS DAVIS BOBBY DAYE LISSA DEGUZMAN MATHEW DEGUZMAN OLIVIA DONALSON MICHAEL EVERETT KARLEE FERREIRA MICHAEL GRACEFFA CLINTON GREENSPAN ADRIENNE HOWARD ALBERT JENNINGS KENWAY HON WAI K. KUA NIKKI LONG JASON SCOTT MACDONALD ANGELINA MULLINS CELINA NIGHTENGALE JAZ SEALEY CHARLES SOUTH MANNY STARK ANNIE WALLACE MICHELLE WEST Co-Producer Technical Supervision Senior Production Supervisor Production Supervisor ANNE QUART GEOFFREY QUART/ CLIFFORD SCHWARTZ JASON TRUBITT HUDSON THEATRICAL ASSOCIATES General Manager Associate Director Dance Supervisor Casting MYRIAH BASH SCOTTY TAYLOR MICHAEL MINDLIN TARA RUBIN CASTING ERIC WOODALL, CSA Music Director/Conductor Dance Music Arrangements Music Coordinator Original Fight Direction Production Stage Manager BRENT-ALAN HUFFMAN GLEN KELLY HOWARD JOINES J. ALLEN SUDDETH MICHAEL MCGOFF Sound Design Hair Design Makeup Design Illusion Design KEN TRAVIS JOSH MARQUETTE MILAGROS MEDINA-CERDEIRA JIM STEINMEYER Costume Design Lighting Design GREGG BARNES NATASHA KATZ Scenic Design BOB CROWLEY Orchestrations DANNY TROOB Music Supervision Incidental Music & Vocal Arrangements MICHAEL KOSARIN Directed and Choreographed by CASEY NICHOLAW ©Disney 2 PLAYBILL Adam Michael James Courtney Isabelle Jacobs Scott Reed McCalla Jonathan Reggie JC Jerald Weir De Leon Montgomery Vincent Zach Philippe Mike Bencal Arroyo Longo Korie Lee Ellis C.