Common Dermatoses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group D07A (Corticosteroids, Plain) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 4 DISCLAIMER 6 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 7 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Methylprednisolone (ATC: D07AA01) 8 Hydrocortisone (ATC: D07AA02) 9 Prednisolone (ATC: D07AA03) 11 Clobetasone (ATC: D07AB01) 13 Hydrocortisone butyrate (ATC: D07AB02) 16 Flumetasone (ATC: D07AB03) 18 Fluocortin (ATC: D07AB04) 21 Fluperolone (ATC: D07AB05) 22 Fluorometholone (ATC: D07AB06) 23 Fluprednidene (ATC: D07AB07) 24 Desonide (ATC: D07AB08) 25 Triamcinolone (ATC: D07AB09) 27 Alclometasone (ATC: D07AB10) 29 Hydrocortisone buteprate (ATC: D07AB11) 31 Dexamethasone (ATC: D07AB19) 32 Clocortolone (ATC: D07AB21) 34 Combinations of Corticosteroids (ATC: D07AB30) 35 Betamethasone (ATC: D07AC01) 36 Fluclorolone (ATC: D07AC02) 39 Desoximetasone (ATC: D07AC03) 40 Fluocinolone Acetonide (ATC: D07AC04) 43 Fluocortolone (ATC: D07AC05) 46 2 Diflucortolone (ATC: D07AC06) 47 Fludroxycortide (ATC: D07AC07) 50 Fluocinonide (ATC: D07AC08) 51 Budesonide (ATC: D07AC09) 54 Diflorasone (ATC: D07AC10) 55 Amcinonide (ATC: D07AC11) 56 Halometasone (ATC: D07AC12) 57 Mometasone (ATC: D07AC13) 58 Methylprednisolone Aceponate (ATC: D07AC14) 62 Beclometasone (ATC: D07AC15) 65 Hydrocortisone Aceponate (ATC: D07AC16) 68 Fluticasone (ATC: D07AC17) 69 Prednicarbate (ATC: D07AC18) 73 Difluprednate (ATC: D07AC19) 76 Ulobetasol (ATC: D07AC21) 77 Clobetasol (ATC: D07AD01) 78 Halcinonide (ATC: D07AD02) 81 LIST OF AUTHORS 82 3 INTRODUCTION The availability of medicines with or without a medical prescription has implications on patient safety, accessibility of medicines to patients and responsible management of healthcare expenditure. The decision on prescription status and related supply conditions is a core competency of national health authorities. -

General Dermatology an Atlas of Diagnosis and Management 2007

An Atlas of Diagnosis and Management GENERAL DERMATOLOGY John SC English, FRCP Department of Dermatology Queen's Medical Centre Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Nottingham, UK CLINICAL PUBLISHING OXFORD Clinical Publishing An imprint of Atlas Medical Publishing Ltd Oxford Centre for Innovation Mill Street, Oxford OX2 0JX, UK tel: +44 1865 811116 fax: +44 1865 251550 email: [email protected] web: www.clinicalpublishing.co.uk Distributed in USA and Canada by: Clinical Publishing 30 Amberwood Parkway Ashland OH 44805 USA tel: 800-247-6553 (toll free within US and Canada) fax: 419-281-6883 email: [email protected] Distributed in UK and Rest of World by: Marston Book Services Ltd PO Box 269 Abingdon Oxon OX14 4YN UK tel: +44 1235 465500 fax: +44 1235 465555 email: [email protected] © Atlas Medical Publishing Ltd 2007 First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Clinical Publishing or Atlas Medical Publishing Ltd. Although every effort has been made to ensure that all owners of copyright material have been acknowledged in this publication, we would be glad to acknowledge in subsequent reprints or editions any omissions brought to our attention. A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN-13 978 1 904392 76 7 Electronic ISBN 978 1 84692 568 9 The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, that the dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. -

Steroid-Induced Rosacealike Dermatitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION Steroid-Induced Rosacealike Dermatitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature Amy Y-Y Chen, MD; Matthew J. Zirwas, MD RELEASE DATE: April 2009 TERMINATION DATE: April 2010 The estimated time to complete this activity is 1 hour. GOAL To understand steroid-induced rosacealike dermatitis (SIRD) to better manage patients with the condition LEARNING OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this activity, dermatologists and general practitioners should be able to: 1. Explain the clinical features of SIRD, including the 3 subtypes. 2. Evaluate the multifactorial pathogenesis of SIRD. 3. Recognize the importance of a detailed patient history and physical examination to diagnose SIRD. INTENDED AUDIENCE This CME activity is designed for dermatologists and generalists. CME Test and Instructions on page 195. This article has been peer reviewed and approved Einstein College of Medicine is accredited by by Michael Fisher, MD, Professor of Medicine, the ACCME to provide continuing medical edu- Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Review date: cation for physicians. March 2009. Albert Einstein College of Medicine designates This activity has been planned and imple- this educational activity for a maximum of 1 AMA mented in accordance with the Essential Areas PRA Category 1 Credit TM. Physicians should only and Policies of the Accreditation Council for claim credit commensurate with the extent of their Continuing Medical Education through the participation in the activity. joint sponsorship of Albert Einstein College of This activity has been planned and produced in Medicine and Quadrant HealthCom, Inc. Albert accordance with ACCME Essentials. Dr. Chen owns stock in Merck & Co, Inc. Dr. Zirwas is a consultant for Coria Laboratories, Ltd, and is on the speakers bureau for Astellas Pharma, Inc, and Coria Laboratories, Ltd. -

Common Dermatological Conditions

Produced: 13/01/2017 Common Dermatological Conditions Dr Alvin Chong Senior Lecturer Dr Catherine Scarff Senior Lecturer Dr Laura Scardamaglia Clinical Senior Lecturer Produced: 13/01/2017 Learning objectives: Describe the common features of • Eczema variants and psoriasis • Acne and rosacea • Scabies • Understand the principles of investigation and treatment for common dermatological problems Produced: 13/01/2017 Case: A 22 year old student presents with 3 months of worsening rash. Not responding to 1% hydrocortisone cream. Produced: 13/01/2017 Erythematous, ill defined, scaly, patches in flexures Produced: 13/01/2017 Diagnosis: Atopic eczema Produced: 13/01/2017 Atopic Eczema • Genetic predisposition Clinical features (Family history) • Itchy ++ • Atopic triad • Erythematous - Asthma • Diffuse - Hayfever • Flexural- thinnest skin - Eczema • Worse in winter (dry) • Worse in summer (heat) Produced: 13/01/2017 Atopic Eczema Model Genetic Predisposition Environmental -Filaggrin mutation- Triggers Leads to reduced barrier •Irritants (soaps etc) function •Allergy •Heat •Infection (Staph.) •“Itch-scratch cycle” •Stress and anxiety 1. Palmer et al Nat. Genet. 38,441-6 Eczema Produced: 13/01/2017 Atopic eczema in an infant Produced: 13/01/2017 3 year old girl, eczema since infancy Produced: 13/01/2017 35 year old man with longstanding eczema mainly of the flexures. Produced: 13/01/2017 Lichenification: The result of chronic rubbing and scratching Produced: 13/01/2017 Eczema Variants Produced: 13/01/2017 Discoid Eczema • Eczema in annular disc -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,359,748 B1 Drugge (45) Date of Patent: Apr

USOO7359748B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,359,748 B1 Drugge (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 15, 2008 (54) APPARATUS FOR TOTAL IMMERSION 6,339,216 B1* 1/2002 Wake ..................... 250,214. A PHOTOGRAPHY 6,397,091 B2 * 5/2002 Diab et al. .................. 600,323 6,556,858 B1 * 4/2003 Zeman ............. ... 600,473 (76) Inventor: Rhett Drugge, 50 Glenbrook Rd., Suite 6,597,941 B2. T/2003 Fontenot et al. ............ 600/473 1C, Stamford, NH (US) 06902-2914 7,092,014 B1 8/2006 Li et al. .................. 348.218.1 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this k cited. by examiner patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Primary Examiner Daniel Robinson U.S.C. 154(b) by 802 days. (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm—McCarter & English, LLP (21) Appl. No.: 09/625,712 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Jul. 26, 2000 Total Immersion Photography (TIP) is disclosed, preferably for the use of screening for various medical and cosmetic (51) Int. Cl. conditions. TIP, in a preferred embodiment, comprises an A6 IB 6/00 (2006.01) enclosed structure that may be sized in accordance with an (52) U.S. Cl. ....................................... 600/476; 600/477 entire person, or individual body parts. Disposed therein are (58) Field of Classification Search ................ 600/476, a plurality of imaging means which may gather a variety of 600/162,407, 477, 478,479, 480; A61 B 6/00 information, e.g., chemical, light, temperature, etc. In a See application file for complete search history. preferred embodiment, a computer and plurality of USB (56) References Cited hubs are used to remotely operate and control digital cam eras. -

Bartholinitis

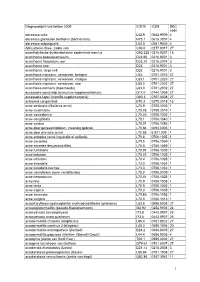

Diagnoselijst Huidziekten 2009 ICD10 ICD9 DBC code abcessus cutis L02.9 0682.9009 4 abcessus glandulae bartholini (bartholinitis) N75.1 0616.3007 4 abcessus subungualis L03.0 0681.9003 4 Abt-Letterer-Siwe, ziekte van C96.0 0277.8017 27 acantholytische dyskeratotische epidermale naevus Q82.222 0216.9297 15 acanthoma basosquamosum D23.90 0216.9001 3 acanthoma fissuratum, oor D23.24 0216.2004 3 acanthoma nno D23 0216.9001 3 acanthoma, large cell D23 0216.9001 3 acanthosis nigricans, verworven, benigne L83. 0701.2016 27 acanthosis nigricans, verworven, maligne L83.1 0701.2023 27 acanthosis nigricans, verworven, nno L83.0 0701.2002 27 acanthosis palmaris (tripe hands) L83.0 0701.2002 27 accessoire oorschelp (auriculum supplementarium) Q17.0 0744.1009 27 accessoire tepel (mamilla supplementaria) Q83.3 0757.6008 27 achromia congenitaal E70.3 0270.2015 16 acne aestivalis (Mallorca acne) L70.9 0706.1005 1 acne cicatricialis L70.05 0709.2019 1 acne comedonica L70.03 0706.1005 1 acne conglobata L70.1 0706.1040 1 acne cystica L70.01 0706.1086 1 acne door geneesmiddelen, inwendig gebruik L70.84 0693.0005 1 acne door olie (olie acne) L70.85 6.921.009 1 acne ectopica (acne inguinalis of axillaris) L70.8 0706.1005 1 acne excoriata L70.5 0706.1069 1 acne excoriee des jeunes filles L70.5 0706.1069 1 acne fulminans L70.81 0706.1005 1 acne indurata L70.02 0706.1005 1 acne infantum L70.4 0706.1028 1 acne keloidalis L73.0 0706.1034 1 acne keloidalis nuchae L73.0 0706.1034 1 acne necroticans (acne varioliformis) L70.2 0706.0009 1 acne neonatorum L70.41 0706.1028 -

Acneiform Dermatoses

Dermatology 1998;196:102–107 G. Plewig T. Jansen Acneiform Dermatoses Department of Dermatology, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, Germany Key Words Abstract Acneiform dermatoses Acneiform dermatoses are follicular eruptions. The initial lesion is inflamma- Drug-induced acne tory, usually a papule or pustule. Comedones are later secondary lesions, a Bodybuilding acne sequel to encapsulation and healing of the primary abscess. The earliest histo- Gram-negative folliculitis logical event is spongiosis, followed by a break in the follicular epithelium. The Acne necrotica spilled follicular contents provokes a nonspecific lymphocytic and neutrophilic Acne aestivalis infiltrate. Acneiform eruptions are almost always drug induced. Important clues are sudden onset within days, widespread involvement, unusual locations (fore- arm, buttocks), occurrence beyond acne age, monomorphous lesions, sometimes signs of systemic drug toxicity with fever and malaise, clearing of inflammatory lesions after the drug is stopped, sometimes leaving secondary comedones. Other cutaneous eruptions that may superficially resemble acne vulgaris but that are not thought to be related to it etiologically are due to infection (e.g. gram- negative folliculitis) or unknown causes (e.g. acne necrotica or acne aestivalis). oooooooooooooooooooo Introduction matory (acne medicamentosa) [1]. The diagnosis of an ac- neiform eruption should be considered if the lesions are The term ‘acneiform’ refers to conditions which super- seen in an unusual localization for acne, e.g. involvement of ficially resemble acne vulgaris but are not thought to be re- distal parts of the extremities (table 1). In contrast to acne lated to it etiologically. vulgaris, which always begins with faulty keratinization Acneiform eruptions are follicular reactions beginning in the infundibula (microcomedones), comedones are usu- with an inflammatory lesion, usually a papule or pustule. -

Drug-Induced Acneform Eruptions: Definitions and Causes Saira Momin, DO; Aaron Peterson, DO; James Q

REVIEW Drug-Induced Acneform Eruptions: Definitions and Causes Saira Momin, DO; Aaron Peterson, DO; James Q. Del Rosso, DO Several drugs are capable of producing eruptions that may simulate acne vulgaris, clinically, histologi- cally, or both. These include corticosteroids, epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, cyclosporine, anabolic steroids, danazol, anticonvulsants, amineptine, lithium, isotretinoin, antituberculosis drugs, quinidine, azathioprine, infliximab, and testosterone. In some cases, the eruption is clinically and his- tologically similar to acne vulgaris; in other cases, the eruption is clinically suggestive of acne vulgaris without histologic information, and in still others, despite some clinical resemblance, histology is not consistent with acne vulgaris.COS DERM rugs are a relatively common cause of involvement; and clearing of lesions when the drug eruptions that may resemble acne clini- is discontinued.1 cally, histologically,Do or both.Not With acne Copy vulgaris, the primary lesion is com- CORTICOSTEROIDS edonal, secondary to ductal hypercor- It has been well documented that high levels of systemic Dnification, with inflammation leading to formation of corticosteroid exposure may induce or exacerbate acne, papules and pustules. In drug-induced acne eruptions, as evidenced by common occurrence in patients with the initial lesion has been reported to be inflammatory Cushing disease.2 Systemic corticosteroid therapy, and, with comedones occurring secondarily. In some cases in some cases, exposure to inhaled or topical corticoste- where biopsies were obtained, the earliest histologic roids are recognized to induce monomorphic acneform observation is spongiosis, followed by lymphocytic and lesions.2-4 Corticosteroid-induced acne consists predomi- neutrophilic infiltrate. Important clues to drug-induced nantly of inflammatory papules and pustules that are acne are unusual lesion distribution; monomorphic small and uniform in size (monomorphic), with few or lesions; occurrence beyond the usual age distribution no comedones. -

Drug-Induced Acneiform Eruptions Drug-Induced Acneiform Eruptions

Provisional chapter Chapter 5 Drug-Induced Acneiform Eruptions Drug-Induced Acneiform Eruptions Emin Özlü and Ayşe Serap Karadağ Emin Özlü and Ayşe Serap Karadağ Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/65634 Abstract Acne vulgaris is a chronic skin disease that develops as a result of inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit and its clinical course is accompanied by comedones, papules, pus- tules, and nodules. A different group of disease, which is clinically similar to acne vul- garis but with a different etiopathogenesis, is called “acneiform eruptions.” In clinical practice, acneiform eruptions are generally the answer of the question “What is it if it is not an acne?” Although there are many subgroups of acneiform eruptions, drugs are common cause of acneiform eruptions, and this clinical picture is called “drug-induced acneiform eruptions.” There are many drugs related to drug-induced acneiform erup- tions. Discontinuation of the responsible drug is generally sufficient in treatment. Keywords: acne, cutaneous toxicities, drug-induced acneiform eruptions, papule, pustule 1. Introduction Acne vulgaris (AV) is a common skin disorder, which affects almost 85% of individuals at least once during life time. Although AV pathogenesis is not clearly understood yet, increased sebum production, androgenic hormones, ductal hypercornification, abnormal follicular keratinization, colonization of Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes), inflammation, and genetic predisposition have been suggested to enhance acne development [1]. Hormone-dependent juvenile acne is a more frequent subgroup, whereas mechanical and drug-induced acne, which are particularly encountered during adulthood, are associated with the drug use with specific underlying etiologies [2]. -

Updates in the Understanding and Treatments of Skin & Hair Disorders in ☆ ☆☆ ★ Women of Color ,

International Journal of Women's Dermatology 3 (2017) S21–S37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Women's Dermatology Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in ☆ ☆☆ ★ women of color , , Christina N. Lawson, MD a,b,⁎, Jasmine Hollinger, MD a, Sumit Sethi, MD c, Ife Rodney, MD a, Rashmi Sarkar, MD c, Ncoza Dlova, MBChB, FCDerm (SA) d, Valerie D. Callender, MD a,b a Department of Dermatology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, District of Columbia b Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center, Glenn Dale, Maryland c Department of Dermatology, Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Hospitals, New Delhi, India d Department of Dermatology, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa article info abstract Article history: Skin of color comprises a diverse and expanding population of individuals. In particular, women of color repre- Received 22 December 2014 sent an increasing subset of patients who frequently seek dermatologic care. Acne, melasma, and alopecia are Received in revised form 15 April 2015 among the most common skin disorders seen in this patient population. Understanding the differences in the Accepted 15 April 2015 basic science of skin and hair is imperative in addressing their unique needs. Despite the paucity of conclusive data on racial and ethnic differences in skin of color, certain biologic differences do exist, which affect the disease presentations of several cutaneous disorders in pigmented skin. While the overall pathogenesis and treatments for acne in women of color are similar to Caucasian men and women, individuals with darker skin types present more frequently with dyschromias from acne, which can be difficult to manage. -

Acne Related to Dietary Supplements

UC Davis Dermatology Online Journal Title Acne related to dietary supplements Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9rp7t2p2 Journal Dermatology Online Journal, 26(8) Authors Zamil, Dina H Perez-Sanchez, Ariadna Katta, Rajani Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/D3268049797 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Volume 26 Number 8| Aug 2020| Dermatology Online Journal || Commentary 26(8):2 Acne related to dietary supplements Dina H Zamil1 BS, Ariadna Perez-Sanchez2 MD, Rajani Katta3 MD Affiliations: 1Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA, 2University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA, 3McGovern Medical School at University of Texas Health Houston, Houston, Texas, USA Corresponding Author: Rajani Katta MD, 6800 West Loop South, Suite 180, Bellaire, TX 77401, Tel: 281-501-3150, Email: [email protected] Drugs that may induce acne include corticosteroids, Abstract anabolic-androgenic steroids, hormonal drugs, Multiple prescription medications may cause or lithium, antituberculosis medications, and drugs that aggravate acne. A number of dietary supplements contain halogens, specifically iodides and bromides have also been linked to acne, including those [1-7]. There are also reports of acne potentially containing vitamins B6/B12, iodine, and whey, as well induced by cancer therapies, immunosuppressants, as “muscle building supplements” that may be and autoimmune disease medications [7]. contaminated with anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS). Acne linked to dietary supplements generally Multiple dietary supplements have also been linked resolves following supplement discontinuation. to acne. A number of case reports and series have Lesions associated with high-dose vitamin B6 and described the onset of acne with certain dietary B12 supplements have been described as supplements, with resolution following monomorphic and although pathogenesis is discontinuation of supplement use. -

Hair Disorders in Women of Color☆,☆☆

International Journal of Women's Dermatology 1 (2015) 59–75 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Women's Dermatology Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color☆,☆☆ Christina N. Lawson, MD a,b,⁎, Jasmine Hollinger, MD a, Sumit Sethi, MD c, Ife Rodney, MD a, Rashmi Sarkar, MD c, Ncoza Dlova, MBChB, FCDerm (SA) d, Valerie D. Callender, MD a,b a Department of Dermatology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, District of Columbia b Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center, Glenn Dale, Maryland c Department of Dermatology, Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Hospitals, New Delhi, India d Department of Dermatology, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa article info abstract Article history: Skin of color comprises a diverse and expanding population of individuals. In particular, women of color repre- Received 22 December 2014 sent an increasing subset of patients who frequently seek dermatologic care. Acne, melasma, and alopecia are Received in revised form 15 April 2015 among the most common skin disorders seen in this patient population. Understanding the differences in the Accepted 15 April 2015 basic science of skin and hair is imperative in addressing their unique needs. Despite the paucity of conclusive data on racial and ethnic differences in skin of color, certain biologic differences do exist, which affect the disease presentations of several cutaneous disorders in pigmented skin. While the overall pathogenesis and treatments for acne in women of color are similar to Caucasian men and women, individuals with darker skin types present more frequently with dyschromias from acne, which can be difficult to manage.