RETRO THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The BOLLI Journal

The BOLLI Journal Volume Ten 2019-2020 Brandeis Osher Lifelong Learning Institute 1 The BOLLI Journal 2019-2020 Table of Contents Editorial Committee WRITING: Creative Nonfiction Sue Wurster, Production Editor Joanne Fortunato, Artistic Editor Short-Changed, Marty Kafka............................................7 The Kiss, Larry Schwirian...............................................10 Literary Editors The Cocoanut Grove, Wendy Richardson.......................12 Speaking of Shells, Barbara Jordan..... ...........................14 Them Bones, Them Bones Marjorie Arons-Barron , Donna Johns........................16 The Hoover Dam Lydia Bogar , Mark Seliber......................................18 Betsy Campbell Dennis Greene Donna Johns THREE-DIMENSIONAL ART Marjorie Roemer Larry Schwirian Shaker Cupboard, Howard Barnstone.............................22 Sue Wurster Fused Glass Pieces, Betty Brudnick...............................23 Mosaic Swirl, Amy Lou Marks.......................................24 Art Editors WRITING: Memoir Helen Abrams Joanne Fortunato A Thank You, Sophie Freud..............................................26 Miriam Goldman Excellent Work, Jane Kays...............................................28 Caroline Schwirian Reaching the Border, Steve Asen....................................30 First Tears, Kathy Kuhn..................................................32 An Unsung Hero, Dennis Greene....................................33 BOLLI Staff Harry, Steve Goldfinger..................................................36 My -

Entertainmentpage 19 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 • 19

ENTERTAINMENTpage 19 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 • 19 FLOUNDERING VOLLEY TECH HOSTS MODEL UN Tech’s women’s volleyball team lost Students from Southeastern high ENTERTAINMENT Tuesday to undefeated Clemson. Th eir schools came to attend the 9th annual Page 33 Page 11 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 record has dropped to 5-4. Model UN Conference. Fall gets cool with fun festivals Food festival serves it up Atlanta unmasks Echo By Hahnming Lee By Hahnming Lee & Jarrett Oakley Sports Editor Sports Editor/Contributing Writer Taste of Atlanta attracted thousands to sample some of Atlanta’s Th is past weekend saw the inaugural run of a new music festival best food this past weekend at Atlantic Station. Starting Oct. 13, based in Atlanta: the Echo Project, which aimed to inform and this special two-day event hosted several of the most popular promote ecologically friendly advice and knowledge about the and acclaimed restaurants in the area, giving them a chance human footprint that’s destroying the environment. to show off their food to the public. Stands were Some 15,000 green-conscious patrons showed set up on the sidewalks of Atlantic Station, with up to see 80-plus bands on this fi rst of at least 10 chefs and waiters preparing signature dishes for annual music festival extravaganzas Oct. 12-14, people roaming the street. set on the beautiful 350-plus acres of Bouckaert Customers purchased entrance tickets and food Farm just 20 minutes south of Atlanta. coupons for the event that could be spent at vari- Along with a myriad of sponsors and vendors ous stands at their discretion. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

The Journal of the Core Curriculum Volume XII Spring 2003 the Journal of the Core Curriculum

The Journal of the Core Curriculum Volume XII Spring 2003 The Journal of the Core Curriculum Volume XII Julia Bainbridge, EDITOR Zachary Bos, ART DIRECTOR Agnes Gyorfi, LAYOUT EDITORIAL BOARD Brittany Aboutaleb Kristen Cabildo Kimberly Christensen Jehae Kim Heather Levitt Nicole Loughlin Cassandra Nelson Emily Patulski Christina Wu James Johnson, DIRECTOR of the CORE CURRICULUM and FACULTY ADVISOR PUBLISHED by BOSTON UNIVERSITY at BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, in the month of MAY, 2003 My mother groan'd! my father wept. Into the dangerous world I leapt: Hapless, naked, piping loud: Like a fiend hid in a cloud. ~William Blake Copyright © MMIII by the Trustees of Boston University. Reproduction of any material contained herein without the expressed consent of the authors is strictly forbidden. Printed 2003 by Offset Prep. Inc., North Quincy, Massachusetts. Table of Contents In the Beginning 7 Stephanie Pickman Love 10 Jonathon Wooding Sans Artifice 11 Ryan Barrett A Splintering 18 Jaimee Garbacik Ripeness and Rot in Shakespeare 22 Stephen Miran Interview with the Lunatic: A Psychiatric 28 Counseling Session with Don Quixote Emily Patulski In My Mind 35 Julia Schumacher On Hope and Feathers 37 Matt Merendo Exploration of Exaltation: A Study of the 38 Methods of James and Durkheim Julia Bainbridge Today I Saw Tombstones 43 Emilie Heilig A Dangerous Journey through the Aisles of Shaw’s 44 Brianna Ficcadenti Searching for Reality: Western and East Asian 48 Conceptions of the True Nature of the Universe Jessica Elliot Journey to the Festival 56 Emilie -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

APPEAL to the CHRISTIAN WOMEN of the SOUTH, by A. E. GRIMKÉ. "Then Mordecai Commanded to Answer Esther, Think Not Within

APPEAL TO THE CHRISTIAN WOMEN OF THE SOUTH, BY A. E. GRIMKÉ. "Then Mordecai commanded to answer Esther, Think not within thyself that thou shalt escape in the king's house more than all the Jews. For if thou altogether holdest thy peace at this time, then shall there enlargement and deliverance arise to the Jews from another place: but thou and thy father's house shall be destroyed: and who knoweth whether thou art come to the kingdom for such a time as this. And Esther bade them return Mordecai this answer: and so will I go in unto the king, which is not according to law, and if I perish, I perish." Esther IV. 13-16. RESPECTED FRIENDS, It is because I feel a deep and tender interest in your present and eternal welfare that I am willing thus publicly to address you. Some of you have loved me as a relative, and some have felt bound to me in Christian sympathy, and Gospel fellowship; and even when compelled by a strong sense of duty, to break those outward bonds of union which bound us together as members of the same community, and members of the same religious denomination, you were generous enough to give me credit, for sincerity as a Christian, though you believed I had been most strangely deceived. I thanked you then for your kindness, and I ask you now, for the sake of former confidence and former friendship, to read the following pages in the spirit of calm investigation and fervent prayer. It is because you have known me, that I write thus unto you. -

I Am the Owner and Founder, Author of One Resolutions Plan to Help Consolidate HUD from 9 Into One Cohesive Operation for the Future

From: Glenn Mendiaz One Resolution Services [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Monday, April 17, 2017 11:02 PM To: FiduciaryRuleExamination - EBSA Subject: One Resolution Services I am the owner and founder, author of One resolutions plan to help consolidate HUD from 9 into one cohesive operation for the future. The labor dispute is simple was I forced out of business while the government to ideas through open govt!! I have received several federal registers, HUD, documents, and a severance package to shore up our relationship and team together to build a share and release operational programs that work for everyone!! Reference ITEMS - 1. i SPOKE TO THE INDIAN PRESIDENT MICHAEL PREITO 2. I WROTE THE USICH PLAN IN 2009 IF NOT COMPLETE READ THEIR PLAN AND ASK ME QUESTIONS I CAN ANSWER THEM WITHOUT NOTES OUT OF MY HEAD AND BRAIN THAT WROTE THE ITEMS. 3. ONE WANTS TO SET UP A HIGH LEVEL MEETING TO DISCUSS HOW ONE RESOLUTION SERVICES CAN HELP! ONE ONCE OPERATIONAL WITH A BUDGET AND MY TEAM IN PLACE. 4. I PROPOSED 9 CHANGES TO DOD FRANK TO HELP! 5. MY TACTICS ARE NOT TRADITIONAL BUT THEY ARE HONEST IM NOT FOR THE GOVERNMENT IM A PUBLIC CITIZEN ASK ME ILL TELL YO THE TRUTH AND PROVIDE SOLUTION.... 27 YEARS IN REAL ESTATE 10 YEAR OF CONSTRUCTION AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT WHILE OTHERS WERE AT SCHOOL I WAS CLOSING DEALS....NOW THEY CALL ME I AM NOT AFRAID AND NOT AFRAID TO UNDERGO MORE ..... MY NAME IS GLENN MENDIAZ IM HERE TO HELP! TAKE TIME TO LISTEN AND I WILL OPEN YOU EYES TO THE REALITY OF TODAY AND THE FUTURE...WE CAN BE BETTER!! MY GOAL IS TO LOOK FORWARD TO SHOW WHAT WE CAN DO BETTER, WHY WE ARE NOT GOING TO MAKE THE MISTAKES OF THE PAST AND TO PUSH SPEAK AND SHARE LEARN THE IDEAS OF OTHERS TO KEEP EVERYONE LOOKING TO THE FUTURE...... -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Paul Mccartney – New • Mary J Blige – a Mary

Paul McCartney – New Mary J Blige – A Mary Christmas Luciano Pavarotti – The 50 Greatest Tracks New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI13-42 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921602 Price Code: SPS Order Due: Release Date: October 22, 2013 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 6 02537 53232 2 Key Tracks: ROAR ROAR Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM (DELUXE) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921502 Price Code: AV Order Due: October 22, 2013 Release Date: October 22, 2013 6 02537 53233 9 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: Key Tracks: ROAR Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM (VINYL) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921401 Price Code: FB Order Due: October 22, 2013 Release Date: October 22, 2013 6 02537 53234 6 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: Key Tracks: Vinyl is one way sale ROAR Project Overview: With global sales of over 10 million albums and 71 million digital singles, Katy Perry returns with her third studio album for Capitol Records: PRISM. Katy’s previous release garnered 8 #1 singles from one album (TEENAGE DREAM). She also holds the title for the longest stay in the Top Ten of Billboard’s Hot 100 – 66 weeks – shattering a 20‐year record. Katy Perry is the most‐followed female artist on Twitter, and has the second‐largest Twitter account in the world, with over 41 million followers. -

Remembering Hugh Masekela: the Horn Player with a Shrewd Ear for Music of the Day

1/24/2018 Remembering Hugh Masekela: the horn player with a shrewd ear for music of the day Academic rigour, journalistic flair Remembering Hugh Masekela: the horn player with a shrewd ear for music of the day October 29, 2017 1.12pm SAST •Updated January 23, 2018 10.13am SAST Hugh Masekela performing during the 16th Cape Town International Jazz Festival. Esa Alexander/The Times Trumpeter, flugelhorn-player, singer, composer and activist Hugh Ramapolo Masekela Author has passed away after a long battle with prostate cancer. When he cancelled his appearance last year at the Johannesburg Joy of Jazz Festival, taking time out to deal with his serious health issues, fans were forced to return to his recorded opus for reminders of his unique work. Listening through that half-century of Gwen Ansell Associate of the Gordon Institute for disks, the nature and scope of the trumpeter’s achievement becomes clear. Business Science, University of Pretoria Masekela had two early horn heroes. The first was part-mythical: the life of jazz great Bix Biederbecke filtered through Kirk Douglas’s acting and Harry James’s trumpet, in the 1950 movie “Young Man With A Horn”. Masekela saw the film as a schoolboy at the Harlem Bioscope in Johannesburg’s Sophiatown. The erstwhile chorister resolved “then and there to become a trumpet player”. The second horn hero, unsurprisingly, was Miles Davis. And while Masekela’s accessible, storytelling style and lyrical instrumental tone are very different, he shared one important characteristic with the American: his life and music were marked by constant reinvention. -

Off-Beats and Cross Streets: a Collection of Writing About Music, Relationships, and New York City

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Stonecoast MFA Student Scholarship 2020 Off-Beats and Cross Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City Tyler Scott Margid University of Southern Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast Recommended Citation Margid, Tyler Scott, "Off-Beats and Cross Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City" (2020). Stonecoast MFA. 135. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast/135 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stonecoast MFA by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Off-Beats and Cross-Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUTREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE, STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITINC BY Tyler Scott Margid 20t9 THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING November 20,2019 We hereby recommend that the thesis of Tyler Margid entitled OffÙeats and Cross- Streets be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Advisor Florio -'1 4rl:ri'{" ¡ 'l¡ ¡-tÁ+ -- Reader Debra Marquart Director J Accepted ¿/k Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Adam-Max Tuchinsky At¡stract Through a series of concert reviews, album reviews, and personal essays, this thesis tracks a musical memoir about the transition from a childhood growing up in a sheltered Connecticut suburb to young adulthood working in New York City, discovering relationships and music scenes that shape the narrator's senss of identity as well the larger culture he f,rnds himself in. -

Internet Search 1999

Internet Research On Rhythm Bones October 1999 Steve Wixson 1060 Lower Brow Road Signal Mountain, TN 37377 423/886-1744 [email protected] Introduction This document presents the current state of 'bone playing' and includes the results of a web search using several search engines for 'rhythm bones', 'rattling bones' and 'bone playing'. It is fairly extensive, but obviously not complete. The web addresses are accurate at the time of the search, but they can go out of date quickly. Web information pertaining to bones was extracted from each website. Some of this information may be copyrighted, so anyone using it should check that out. Text in italics is from e-mail and telephone conversations. We would appreciate additions - please send to name at end of this document. The following is William Sidney Mount's 'The Bone Player.' A. General 1. http://mcowett.home.mindspring.com/BoneFest.html. 'DEM BONES, 'DEM BONES, 'DEM RHYTHM BONES! Welcome to Rhythm Bones Central The 1997 Bones Festival. Saturday September 20, 1997 was just another normal day at "the ranch". The flag was run up the pole at dawn, but wait -----, bones were hanging on the mail box. What gives? This turns out to be the 1st Annual Bones Festival (of the century maybe). Eleven bones-players (bone-player, boner, bonist, bonesist, osyonist, we can't agree on the name) and spouses or significant others had gathered by 1:00 PM to share bones-playing techniques, instruments and instrument construction material, musical preferences, to harmonize and to have great fun and fellowship. All objectives were met beyond expectations. -

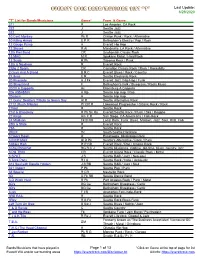

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO