Attorney General of Saskatchewan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carissima Mathen*

C h o ic es a n d C o n t r o v e r sy : J udic ia l A ppointments in C a n a d a Carissima Mathen* P a r t I What do judges do? As an empirical matter, judges settle disputes. They act as a check on both the executive and legislative branches. They vindicate human rights and civil liberties. They arbitrate jurisdictional conflicts. They disagree. They bicker. They change their minds. In a normative sense, what judges “do” depends very much on one’s views of judging. If one thinks that judging is properly confined to the law’s “four comers”, then judges act as neutral, passive recipients of opinions and arguments about that law.1 They consider arguments, examine text, and render decisions that best honour the law that has been made. If judging also involves analysis of a society’s core (if implicit) political agreements—and the degree to which state laws or actions honour those agreements—then judges are critical players in the mechanisms through which such agreement is tested. In post-war Canada, the judiciary clearly has taken on the second role as well as the first. Year after year, judges are drawn into disputes over the very values of our society, a trend that shows no signs of abating.2 In view of judges’ continuing power, and the lack of political appetite to increase control over them (at least in Canada), it is natural that attention has turned to the process by which persons are nominated and ultimately appointed to the bench. -

The Rt. Hon. Antonio Lamer, Chief Justice of Canada and of the Supreme Court of Canada, Is Pleased to Welcome Mr

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA PRESS RELEASE OTTAWA, January 8,1998 -- The Rt. Hon. Antonio Lamer, Chief Justice of Canada and of the Supreme Court of Canada, is pleased to welcome Mr. Justice Ian Binnie to the Court. He stated: “I am very pleased that in the legacy of our late colleague, John Sopinka, another member of the Court has been selected directly from the legal profession. It is important that this Court always be aware of the realities of the practising Bar so that we do not lose sight of the practical effect of our judgments. I am sure that Mr. Justice Binnie, who is counsel of the highest standing in the profession, will make a very valuable and lasting contribution to this Court.” Chief Justice Lamer spoke to Mr. Justice Binnie this morning to congratulate him on his appointment. Mr. Justice Binnie has indicated that he will be available to commence his duties at the Court as of the 26th of January. However, he will not be sitting that week, nor during the two following weeks as the Court is in recess, in order that he may prepare for the Quebec Reference case which will proceed, as scheduled, during the week of February 16th. Mr. Justice Binnie’s swearing-in will take place on February 2, 1998 at 11:00 a.m. in the main courtroom. Ref.: Mr. James O’Reilly Executive Legal Officer (613) 996-9296 COUR SUPRÊME DU CANADA COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE OTTAWA, le 8 janvier 1998 -- Le très honorable Antonio Lamer, Juge en chef du Canada et de la Cour suprême du Canada, a le plaisir d’accueillir M. -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays by a Very Public 41 Edited by John -

A Survivor's Guide to Advocacy in the Supreme Court of Canada

Ulls dcl cr~rnla\\'. edd Nov ?7!VX 98'29 A SURVIVOR'S GUIDE TO ADVOCACY IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA by: Mr. Justice Ian Binnie Supreme Court of Canada The jol1occ:ing is an edired, erc. fexr ojrhe $rsr John Sopinkn Advocacy Lecrure presenred ro zhe Criminal Lawyers' Associarion ar Toronro, on November 27, 1998. Thank you very much Allan [Gold]. I am very honoured by the invitation to speak today. John Sopinka died almost exactly a year ago this week and it is very fitting for the Criminal Lawyers' Association to inaugurate this series of lectures to perpetuate and to honour his great talent. It is a double honour to have John's daughter Melanie here. She not only shares her Dad's feistiness, but is, as her oppocents have come to appreciate, a very considerable advocate in her own right. It seems somewhat less fitting that I should be called on to give the first of these lectures. John Sopinka fit neatly into the long line of heroic counsel reaching back to Edward Blake. and descending through W. N. Tilley to John Robinene and others, including Bert Mackimon and John's contemporary, Ian Scon, in our own day. The most I can claim is that I am a survivor, but in this room we are all sunivors. What I have to say today should therefore be seen as a survivor's guide to advocacy in the Supreme Court of Canada. The first point I want to make about John Sopinka is that he was a man with an attitude - only in extreme circumstances would he tug his forelock or use the phrase "May it please the court". -

Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arran

■ Diversifying the bar: lawyers make history Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present Click here to download Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 1: 1797 to 1941 For each lawyer, this document offers some or all of the following information: name gender year and place of birth, and year of death where applicable year called to the bar in Ontario (and/or, until 1889, the year admitted to the courts as a solicitor; from 1889, all lawyers admitted to practice were admitted as both barristers and solicitors, and all were called to the bar) whether appointed K.C. or Q.C. name of diverse community or heritage biographical notes name of nominating person or organization if relevant sources used in preparing the biography (note: living lawyers provided or edited and approved their own biographies including the names of their community or heritage) suggestions for further reading, and photo where available. The biographies are ordered chronologically, by year called to the bar, then alphabetically by last name. To reach a particular period, click on the following links: 1941-1950, 1951-1960, 1961-1970, 1971-1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, 2001-. To download the biographies of lawyers called to the bar before 1941, please click Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present For more information on the project, including the set of biographies arranged by diverse community rather than by year of call, please click here for the Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History home page. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

Must a Judge Be a Monk - Revisited

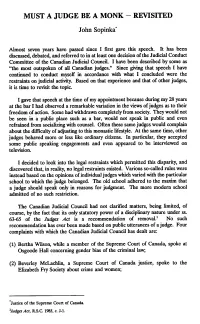

MUST A JUDGE BE A MONK - REVISITED John Sopinka* Almost seven years have passed since I first gave this speech. It has been discussed, debated, and referred to in at least one decision of the Judicial Conduct Committee of the Canadian Judicial Council. I have been described by some as “the most outspoken of all Canadian judges.” Since giving that speech I have continued to conduct myself in accordance with what I concluded were the restraints on judicial activity. Based on that experience and that of other judges, it is time to revisit the topic. I gave that speech at the time of my appointment because during my 28 years at the bar I had observed a remarkable variation in the views of judges as to their freedom of action. Some had withdrawn completely from society. They would not be seen in a public place such as a bar, would not speak in public and even refrained from socializing with counsel. Often these same judges would complain about the difficulty of adjusting to this monastic lifestyle. At the same time, other judges behaved more or less like ordinary citizens. In particular, they accepted some public speaking engagements and even appeared to be interviewed on television. I decided to look into the legal restraints which permitted this disparity, and discovered that, in reality, no legal restraints existed. Various so-called rules were instead based on the opinions of individual judges which varied with the particular school to which the judge belonged. The old school adhered to the maxim that a judge should speak only in reasons for judgment. -

Cool & Unusual Advocates

The The INSIDE Law School Practice Makes Perfect: Clinical training gives students The a professional edge. The Family Guy: One professor | T insists that the legal system can HE HE better serve children. Nine maga Lawthe magazine of the new yorkSchool university school of law • autumn 2007 experts debate his ideas. ZI From understanding contract principles to N “ E deciphering federal, state, and local codes OF T and ordinances to negotiating with various HE N parties, the skills I gained during my years Y EW O at the NYU School of Law were invaluable RK in the business world. UN ” IVERSI In 2005, Deborah Im ’04 took time off to pursue a dream: T She opened a “cupcakery” in Berkeley, California, to rave S Y reviews. When she sold the business to practice law again, C H she remembered the Law School with a generous donation. OO L L Our $400 million campaign was launched with another OF L goal: to increase participation by 50 percent. Members A of every class are doing their part to make this happen. W You should know that giving any amount counts. Meeting or surpassing our participation goal would be, well, icing on the cake. Please call (212) 998-6061 or visit us at https://nyulaw.publishingconcepts.com/giving. Nonprofit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Buffalo, NY Office of Development and Alumni Relations Permit No. 559 161 Avenue of the Americas, Fifth Floor New York, NY 10013-1205 autumn 2007, volume X volume 2007, autumn vii Cool & Unusual Advocates Anthony Amsterdam and Bryan Stevenson reveal what compels them to devote their lives to saving the condemned. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian 2008 CanLIIDocs 196 Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

MSS2101 Graphic 1--4; 108--110.Xlsx

John Sopinka fonds MG31-E120 Finding aid no MSS2101 vols. 1--110; 07447; TCS 01429 R1312 Instrument de recherche no MSS2101 Hier. lvl. Media Label File Item Title Scope and content Vol. Dates Niv. Support Étiquette Dossier Pièce Titre Portée et contenu hier. John Sopinka fonds Activities as Justice at the Supreme Court of Canada Bench books 22 June 1989 - 7 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 1 1 Bench Book No. 1 1989 6 Dec. 1989 - 23 Mar. File Textual MG31-E120 1 2 Bench Book No. 2 1990 26 Mar. 1990 - 12 Oct. File Textual MG31-E120 1 3 Bench Book No. 3 1990 29 Oct. 1990 - 27 Feb. File Textual MG31-E120 1 4 Bench Book No. 4 1991 28 Feb. 1991 - 4 July File Textual MG31-E120 1 5 Bench Book No. 5 1991 1 Oct. 1991 - 9 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 1 6 Bench Book No. 6 1991 10 Dec. 1991 - 25 Mar. File Textual MG31-E120 1 7 Bench Book No. 7 1992 26 May 1992 - 11 Dec. File Textual MG31-E120 2 1 Bench Book No. 8 1992 25 Jan. 1993 -27 May File Textual MG31-E120 32 1 Bench Book No. 9 1993 31 May 1993- 26 Jan. File Textual MG31-E120 32 2 Bench Book No. 10 1994 27 Jan. 1994 - 4 Oct. File Textual MG31-E120 32 3 Bench Book No. 11 1993 4 Oct. 1994 - 23 Feb. File Textual MG31-E120 32 4 Bench Book no. 12 1995 24 Feb. 1995 - 3 Nov. File Textual MG31-E120 32 5 Bench Book No. -

The Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Role: an Historical Institutionalist Account

THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA AND THE JUDICIAL ROLE: AN HISTORICAL INSTITUTIONALIST ACCOUNT by EMMETT MACFARLANE A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Studies in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November, 2009 Copyright © Emmett Macfarlane, 2009 i Abstract This dissertation describes and analyzes the work of the Supreme Court of Canada, emphasizing its internal environment and processes, while situating the institution in its broader governmental and societal context. In addition, it offers an assessment of the behavioural and rational choice models of judicial decision making, which tend to portray judges as primarily motivated by their ideologically-based policy preferences. The dissertation adopts a historical institutionalist approach to demonstrate that judicial decision making is far more complex than is depicted by the dominant approaches within the political science literature. Drawing extensively on 28 research interviews with current and former justices, former law clerks and other staff members, the analysis traces the development of the Court into a full-fledged policy-making institution, particularly under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This analysis presents new empirical evidence regarding not only the various stages of the Court’s decision-making process but the justices’ views on a host of considerations ranging from questions of collegiality (how the justices should work together) to their involvement in controversial and complex social policy matters and their relationship with the other branches of government. These insights are important because they increase our understanding of how the Court operates as one of the country’s more important policy-making institutions.