Knowledge, Network Ties, and Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

Mayor Urges Residents: Program a Nn Ounced 5 Reactions Wen G 3T-Eoncert-Band- Will -Pfesent-Its -Annual- —!Stjmd Ilb

Second Class tvrataae VoL LXXII No.9. Sections, 24 Pages dRANFORt), NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, MARCH 18, 1965 Ctvoioti. w. J. TEN CENTfr to Spring Concert Mayor Urges Residents: Program A nn ounced 5 Reactions wen g 3t-eoncert-Band- will -pFesent-its -annual- —!Stjmd_IlB. and Be^ Coimted this week as the old Nortti Av& bridge across the Rafrway Biver sprting concert Saturday evening at 8 o'clock in tSe high school audi- v ? orium. In addition to the Concert Band, the Modern Jazz Sextet, ':'betw^n'''--!^nn;^'eid''' an!i''' ''C>witian^'' • nial Ayes.^ was barricaded at eaeii Modern Stage Band and Vocal Ensemble will perform. end iri.preparationfor its removal • The Concert fiand, under the direction of Robert Yurochko, will ,•' ". - •/,.', •',• ' ;< :*:,-•• / • :'. r"iinclude students from the ninth, to rn^ke way for a newtarid wider. A citizens' meeting to mem* Ithrough 12th grades. Auditions bridge to be installed by the S<ate orialize Rev. James J. .Reeb, Highway E&parttnent.' •.: •?' for students from the Hillside Boston Unitarian minister PoliceChie* Lester W.''Po*ell No Classes Avenue andTDrnnge Avenue Jun- ior High Schools were held in De- Statement by Mayor murdered in Seima, Ala. re- reported, there Were spine delays 1 and inconvenjeiice for motorists cember . cently, and to express concern during r^TpCTi^r rugh- hours- Tues- The Concert Band will open the On Reeb Memorial Meeting for human rights will be held iday evening and yesterday morn-' program by performing '"World's. at 8 p.m. Monday in the Cran- Fair March," by Alfred Antonini; I attended a meeting of 20 citizens of Cranford Mon- - ford High School auditorium. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

Sonny Stitt Och Charlie Parker

Pedagogiskt specialarbete 2009 Gustav Rosén Saxofonisten Sonny Stitt – Stilbildare eller Charlie Parker-kopia? Handledare: Viveka Hellström Kungl. Musikhögskolan i Stockholm Pedagogiskt specialarbete Gustav Rosén Abstract I arbetet undersöker jag saxofonisten Sonny Stitts utveckling och vad som kännetecknar hans spelstil. Tyngdpunkten har lagts på jämförelser med den med Sonny Stitt samtida saxofonisten Charlie Parker, som Stitt ofta anklagats för att ha kopierat. Även jämförelser med saxofonisten Lester Young har blivit nödvändiga. För att ge en bild av Stitt och hans utveckling, har jag också gjort efterforskningar kring hans karriär och samtid. Mitt resultat visar att Stitt hade flera personliga karaktärsdrag, men att influenserna från Charlie Parker i många fall var så starka att Stitts egen personlighet ofta överskuggades. Uppfattningen att han varit en kopia verkar dock vara överdriven. Framför allt som teno- rist kom Stitt att ha en viss betydelse för jazzens utveckling under tidigt 1950-tal, bland annat för saxofonisten John Coltrane. Ett mer allmänt resonemang kring förhållandet mellan elev och förebild inom jazztradi- tionen och behovet av att vara en unik musiker i dagens musikutbildning och musikliv diskuteras i uppsatsen. I ett pedagogiskt perspektiv kan Stitts logiska spel vara bra att fördjupa sig i för den som vill lära sig tala jazzens språk. Jag upptäckte också stora likhe- ter i hur Stitt lärde sig spela och hur de flesta amerikanska jazzutbildningar idag är upp- byggda. – 2 – Pedagogiskt specialarbete Gustav Rosén -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

The Leader 2016

Issue 12 • Summer 2016 e h T Leader Learning to Lead our Lives The Leader cellebrates the achiievements and experiiences of our students and chroniiclles the lliife of the schooll The Leader Issue 12 - Summer 2016 Student Art Holly Sproul Andrew Cole Nicole Bradshaw Chloe Dunmore Cassie De St Croix Bradley Smith Ellen Wise Cyd Rawlins Ellen Wise Abby Carrington Chloe Rushe Jade Corrin Abigail Birchall Lauren Terrell Kelly McGurk Millie Sutton 2 The Leader Issue 12 - Summer 2016 Back to the Future Contents This academic year, saw the actual day when the film ‘Back to the 2 Student Art 3 Back to the Future Future’ was set, 21st October 2015. Around the world, there was much 3 Editorial celebration and comparison to what had been predicted in the film. The 4 A Year in the Life... 6 Head Girl and Boy hope for the future, and predicting what might be, is a constant theme 7 Student Art 8 Sporting Round-up of school and educators. 15 Head in the Clouds 16 Designing J.I.M. fond memories left behind. But I 17 Downhill all the way! believe that it was a great step towards 18 Krakow - Easter 2016 modern education in Monmouth.” 20 Renishaw Engineering Trip 20 CERN 2016 Our school magazine, which records 21 Maddie and Millie the lives of our students, will sometime 22 Interview with Non Evans in the future be read by people who 23 Student Art have not yet been born. The future, 24 Let the Sun Shine….. 25 Going Beyond The Book whilst different, will also be familiar. -

The March in Glasgow

FOit.A · ·BALANCED University of Edinburgh,-Old College South Bridge, Edinburgh 'EHB 9YL vmw Tal: 031-6671011 ext4308 18 November-16 December GET .ALBERT IRVIN Paintings 1959-1989 ~*;£~-- Tues-Sat 10 am-5 pm Admission Free Subsidised by the Scottish Arts Council DAILY G~as~ow Herald _ of the Year y 30rd november 1 RUGBY BACK TO THE. 1st XV FUTUREII s:enttpacking problems of iii Peffenrtill time~ travel~ ·>... page8 .page 1 • I • arc STUDENTS from all over Park just after 2 pm, and con tinued to do so for nearly an hour, the United Kingdom assem with the rally properly beginning bled in Qlasgow on Tuesday around 2.15 pm. to take part in what was prob Three common themes were ably the biggest ever student addressed by the ten public demonstration on the British figures at the rally in the Park: mainland. these were the discriminatory nature of student loans; the com The march organised by the mitment by all to student grants, National Union of Students and the solidarity of support given against the Government's prop by them to students. osed introduction of top-up loans, The first four speakers addres was deemed by Strathclyde Police ·sed the rally from the semi-circu to have attracted around 20,00 lar, covered platform as students people. still marched in through the gates. Certainly, spirits were high All four- Mike Watson , Labour despite the cold and damp dismal MP for Glasgow Central ; Archy weather. It is likely this was a fac Kirkwood, Liberal Demcorat tor in preventing a larger turn MP; Diana Warwick, . -

October 2011

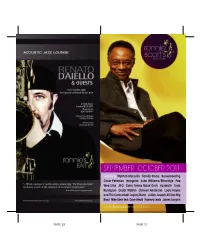

SEPTEMBE R - OCTOBER 2011 Featuring: Wynton Marsalis | Family Stone | Remembering Oscar Peterson | Incognito | John Williams/Etheridge | Pee Wee Ellis | JTQ | Colin Towns Mask Orch | Azymuth | Todd Rundgren | Cedar Walton | Carleen Anderson | Louis Hayes and The Cannonball Legacy Band | Julian Joseph All Star Big Band | Mike Stern feat. Dave Weckl | Ramsey Lewis | James Langton Cover artist: Ramsey Lewis Quintet (Thur 27 - Sat 29 Oct) PAGE 28 PAGE 01 Membership to Ronnie Scotts GIGS AT A GLANCE SEPTEMBER THU 1 - SAT 3: JAMES HUNTER SUN 4: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S JAZZ ORCHESTRA PRESENTS THE GENTLEMEN OF SWING MON 5 - TUE 6: THE FAMILY STONE WED 7 - THU 8: REMEMBERING OSCAR PETERSON FEAT. JAMES PEARSON & DAVE NEWTON FRI 9 - SAT 10: INCOGNITO SUN 11: NATALIE WILLIAMS SOUL FAMILY MON 12 - TUE 13: JOHN WILLIAMS & JOHN ETHERIDGE WED 14: JACQUI DANKWORTH BAND THU 15 - SAT 17: PEE WEE ELLIS - FROM JAZZ TO FUNK AND BACK SUN 18: THE RONNIE SCOTT’S BLUES EXPLOSION MON 19: OSCAR BROWN JR. TRIBUTE FEATURING CAROL GRIMES | 2 free tickets to a standard price show per year* TUE 20 - SAT 24: JAMES TAYLOR QUARTET SUN 25: A SALUTE TO THE BIG BANDS | 20% off all tickets (including your guests!)** WITH THE RAF SQUADRONAIRES | Dedicated members only priority booking line. MON 26 - TUE 27: ROBERTA GAMBARINI | Jump the queue! Be given entrance to the club before Non CELEBRATING MILES DAVIS 20 YEARS ON Members (on production of your membership card) WED 28 - THU 29: ALL STARS PLAY ‘KIND OF BLUE’ FRI 30 - SAT 1 : COLIN TOWNS’ MASK ORCHESTRA PERFORMING ‘VISIONS OF MILES’ | Regular invites to drinks tastings and other special events in the jazz calendar OCTOBER | Priority information, advanced notice on acts appearing SUN 2: RSJO PRESENTS.. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Jazzlondonlive Dec 2018

Scragg (bass), Ross Stanley (keys), Rick Finlay CAROL KING MEETS NORAH JONES (drums) DEC 2018 Phoebe Katis, vcls & keys, Ed Rice, keys, Ed JAZZLONDONLIVE Ireland, bass 02/12/2018 OVAL TAVERN, CROYDON 13:00 02/12/2018 BULL'S HEAD, BARNES 19:30 £10 IN ADV & 01/12/2018 LE QUECUMBAR, BATTERSEA 11:00 £40 01/12/2018 JAZZ CAFE POSK, RAVENSCOURT PARK TRUDY KERR QUARTET JAZZ IN THE AFTERNOON £12 ON THE DOOR GONZALO BERGARA GYPSY JAZZ MASTERCLASS 20:30 £9 ON THE DOOR, ADVANCE £8, STUDENTS £5. ELAINE HALLAM 'JAZZ-ISH' 02/12/2018 RONNIE SCOTT'S, SOHO 13:00 £15 - £20 Elaine Hallam, vcls, Tim Sharp, pno, Paul Hankin, WERONIKA BIELECKA JAZZ AT THE MOVIES PRESENTS 'A SWINGING perc 01/12/2018 RONNIE SCOTT'S, SOHO 13:00 £75 £80 Weronika Bielecka on Vocals, with Terence Colliie's TC3 plus the Konvalia String Trio CHRISTMAS' LUNCHTIME SHOW CHRISTMAS CABARET LUNCH LUNCHTIME SHOW featuring Agata Kubiak 02/12/2018 RONNIE SCOTT'S, SOHO 19:30 £30 - £45 Glass of Prosecco, 3 course lunch, musical Joanna Eden (voice) Chris Ingham (piano/MC) Duncan Hemstock (clarinet/tenor sax) Arnie CHARLIE WOOD BAND MAIN SHOW entertainment from the fabulous Ronnie Scott’s Somogyi (bass) George Double (drums) All Stars and special guests. Magician, Kazoos 01/12/2018 VORTEX JAZZ CLUB, DALSTON 20:30 £18 Charlie Wood (keys/vocals) Chris Allard (guitar) Dudley Phillips (bass) Nic France (drums) and surprises along the way! DAVID TORN PLUS SONAR 02/12/2018 606 CLUB, CHELSEA 13:30 £10 Quentin Collins (TRUMPET) Brandon Allen (SAX) David Torn (gtr), Stephan Thelen (gtr), Bernhard Mark Nightingale (trombone) 01/12/2018 PIZZAEXPRESS JAZZ CLUB 13:30 £15 Wagner (gtr), Christian Kuntner (bs), Manuel HELEN LOUISE JONES VOCAL-LED MAINSTREAM Pasquinelli (drs) PIXIE & THE GYPSIES JAZZ QUARTET 02/12/2018 TOULOUSE LAUTREC, KENNINGTON 19:30 Helen Louise Jones-vocals, Chris Jerome-piano, 01/12/2018 606 CLUB, CHELSEA 21:30 £14 FREE FOR DINERS 01/12/2018 LE QUECUMBAR, BATTERSEA 18:00 FREE Miles Danso-bass, Sophie Alloway-drums GILAD ATZMON QUARTET SAX-LED MODERN JAZZ NOEMI NUTI FEAT.