Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 111 (August 2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Tucson Special Event Application D

TUCSON ARIZONA, U.S.A. 2017 IFEA WORLD FESTIVAL & EVENT CITY AWARD PRESENTATION TUCSON ARIZONA, U.S.A. 2017 IFEA WORLD FESTIVAL & EVENT CITY AWARD PRESENTATION Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Letter from Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild 3. Section 1: Community Overview ............................................ 1 4. Section 2: Community Festivals and Events ................................. 28 5. Section 3: City/Governmental Community Support of Festivals and Events ....... 54 6. Section 4: Non-Governmental Community Support of Festivals and Events ....... 70 7. Section 5: Leveraging ‘Community Capital’ Created by Festivals and Events ...... 90 8. Section 6: Extra Credit . 108 9. Exhibits A. Recent Awards and Accolades for Tucson B. Additional Festivals and Events Venues C. City of Tucson Special Event Application D. City of Tucson Permitted Festivals and Events FY2017 E. Visit Tucson PR & Communications 10. Special Thanks INTRODUCTION Known unofficially for decades as the Old Pueblo, Tucson is building on its vibrant multicultural heritage to create a more urban, yet uniquely Southwestern-style future. The rest of the nation is taking notice that Tucson is on the upswing—a high quality of life, economic opportunity, lots to do and experience, and a happening dining, arts, entertainment, and local events scene. Tucson is being increasingly recognized for its livability, vitality, and cool factor. Tucson is a place like none other. Surrounded by five mountain ranges—the highest reaching more than 9,000 feet in elevation – and home to giant saguaro and other rare cacti in the heart of the living Sonoran Desert, Tucson enjoys an average 350 days of sunshine each year. Tucson hosts eclectic festivals and events year-round, most of them one-of-a-kind and home- grown, celebrating the region’s history and culture, visual and performing arts, a unique food heritage—Tucson is the first American city to be named a City of Gastronomy by UNESCO— local music, outdoor recreation, nature, science and technology, spectator sports, cycling and running. -

TA-1VP Vocal Processor

D01141720C TA-1VP Vocal Processor OWNER'S MANUAL IMPORTANT SAFETY PRECAUTIONS ªª For European Customers CE Marking Information a) Applicable electromagnetic environment: E4 b) Peak inrush current: 5 A CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER- Disposal of electrical and electronic equipment SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO (a) All electrical and electronic equipment should be QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. disposed of separately from the municipal waste stream via collection facilities designated by the government or local authorities. The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol, within equilateral triangle, is intended to (b) By disposing of electrical and electronic equipment alert the user to the presence of uninsulated correctly, you will help save valuable resources and “dangerous voltage” within the product’s prevent any potential negative effects on human enclosure that may be of sufficient health and the environment. magnitude to constitute a risk of electric (c) Improper disposal of waste electrical and electronic shock to persons. equipment can have serious effects on the The exclamation point within an equilateral environment and human health because of the triangle is intended to alert the user to presence of hazardous substances in the equipment. the presence of important operating and (d) The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the appliance. symbol, which shows a wheeled bin that has been crossed out, indicates that electrical and electronic equipment must be collected and disposed of WARNING: TO PREVENT FIRE OR SHOCK separately from household waste. HAZARD, DO NOT EXPOSE THIS APPLIANCE TO RAIN OR MOISTURE. -

Musicpress.Pdf

スルッとスキニー&億千米 サンプルセットプレゼント中!! Kiss FM KOBE Event Report あ の『 億 千 米 』が パ ウ ダ ー タ イ プ に な っ て 新 登 場 ! ! 2011.6.4 sat @KOBE 植物性乳酸菌で女性の悩みをサポート 6月4日土曜日。週末の三宮の一角、イル・アルバータ神戸の前には鮮やか な黄色の[yellow tail]のフラッグが立ち並んでいた。そこに訪れるのは、 Kiss FMのイベント応募で選ばれた15組30名のワイン好きキスナー達。 店内に入ると、まず目に入るのは入り口近くに置かれた大きなグラス。しか もこちらには、オレンジジュース10Lに赤ワイン16本を注いだという、な んと本物のカクテルが。向かいのバーカウンター横には、セルフでカクテル を作れるスペースも設置されており、自分好みの味を楽しめるようになっ ている。イベントのMCを務めるのは、ワイン好きとしても知られるサウン ド ク ル ー ・ R I B E K A 。こ の 日 の コ ン セ プ ト“ ワ イ ン を 気 軽 に 楽 し む ”た め に 用意されたオリジナルカクテルが紹介される。 グレープフルーツを合わせ、酸味とその美しい青色が見た目にも爽やかな ブルーバブルス。イチゴとオレンジの香りにヨーグルト、 薄いピンク色が女性にも喜ばれそうなピンクテイル。カ シスとコーラによってジュースのように飲みやすいレッド テイル。そんなワインカクテルにぴったりな、イル・アル バータ特製の料理も次々と運ばれ、参加者達は舌鼓を打 お米の乳酸菌を、発酵技術で増やしました。 ちつつワインをゆったりと楽しんだ。 玄米食が苦手な人も思わずにっこりの美味しさです。 この日スペシャルトークゲストとして登場したのはmihimaru GTの 二人。告知なしで目の前に現れたシークレットアーティストに、会場 の歓声が上がる。芦屋出身で、神戸もよく訪れていたというヴォーカ ルhiroko。テーブルに置かれた3種類のカクテルを飲みながら「めっ ち ゃ 美 味 し い ! 」と 関 西 弁 で 嬉 し そ う に 微 笑 ん だ 。R I B E K A が「 ガ ン ガン飲んではるんですけど」と笑う通り、「美味しくて全部飲み干し たい!」と観客を和ませる良い飲みっぷりを披露。新曲『マスターピー Kiss MUSIC PRESS読者限定 ス』の作成秘話や、ソロ活動を経てこれからのmihimaru GTについ てカクテルpartyならではの親しみある雰囲気で語ってくれた。 サ ン プル セットプレ ゼ ント !! 次に登場したのは、ライブゲストのザッハトルテ。ジャズを中心と 下記よりご応募いただいた皆様の中から『スルッとスキ し た 多 ジ ャン ル の 楽 曲 を ア コ ー デ ィ オ ン・ギ タ ー・チ ェ ロ と い う 変 ニー!』3gスティック×5本と億千米25g×2袋を 則的にも思える構成で演奏する彼らだけあって、それぞれの髪型 セットにして300名様にプレゼントいたします! も か な り 個 性 的 。し か し 、一 音 鳴 ら せ ば「 窓 の 外 に 見 え る 三 宮 の 景 色 が 、ま る で パ リ の 街 並 み 」と R I B E K A も 語 る よ う に 、独 特 の 空 気 ■応募方法 感がその場にいる人々の前に作り出される。『素敵な1日』や『それ Kiss FM KOBEのサイトトップページ右側にあるプレゼント パソコン 欄から『スルッとスキニー!&億千米 サンプルセット』を選択、 で も セ ー ヌ は 流 れ る 』な -

Casiopea 1979 Full Album Download

casiopea 1979 full album download IsraBox - Music is Life! Casiopea - Best of Casiopea-Alfa Collection (2009) Artist : Casiopea Title : Best of Casiopea-Alfa Collection Year Of Release : 2009 Label : Alfa Records Genre : Jazz, Jazz Fusion Quality : MP3/320 kbps Total Time : 77:28 Total Size : 183 MB(+3%) Casiopea - Jive Jive (2002) [24bit FLAC] Artist : Casiopea Title : Jive Jive Year Of Release : 1983 / 2002 Label : Village Records / Alfa – ALR 28052 / Vinyl, LP Genre : Jazz-Rock, Jazz- Funk, Smooth Jazz, Fusion Quality : FLAC (tracks+.cue,log scans) / FLAC (tracks) 24bit-192kHz Total Time : 38:18 Total Size : 245 Mb / 1.48 Gb. Casiopea - Dramatic (1993) Artist : Casiopea Title : Dramatic Year Of Release : 1993 Label : Alfa Records Genre : Jazz, Fusion Quality : FLAC (tracks+.cue, log) Total Time : 51:04 Total Size : 351 MB. Casiopea - Answers (1994) Artist : Casiopea Title : Answers Year Of Release : 1994 Label : Alfa Genre : Smooth Jazz, Jazz-Funk, Fusion Quality : FLAC (image+.cue, log, Artwork) Total Time : 54:13 Total Size : 356 MB. Casiopea - Material (1999) CD Rip. Artist : Casiopea Title : Material Year Of Release : 1999 Label : Pony Canyon[PCCR-00304] Genre : Jazz, Fusion Quality : FLAC (tracks + .cue,log,scans) Total Time : 49:15 Total Size : 323 MB(+3%) Casiopea - Down Upbeat (1984) Artist : Casiopea Title : Down Upbeat Year Of Release : 1984 Label : Alfa Records Genre : jazz, funk, fusion Quality : APE (image+.cue,log,scans) Total Time : 38:26 Total Size : 228 MB. Casiopea - Main Gate (2001) Artist : Casiopea Title : Main -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship. WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA How to cite: WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA (2018) Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13052/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship Eris Kathlyn Laura Williams-Reed A thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History Durham University 2018 Acknowledgments It is a joy to recall the many people who, each in their own way, made this thesis possible. Firstly, I owe a great deal of thanks to my supervisor, Ted Kaizer, for his support and encouragement throughout my doctorate, as well as my undergraduate and postgraduate studies. -

Policies and Procedures – Living at the Valley

Policies and Procedures – Living at the Valley Updated: September, 2018 ALARMS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 COMMUNICATION .................................................................................................................................................................1 CONTRACTOR HOURS ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 DOG PARK & LEASH REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................................................ 2 DRAINAGE ….............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 DRIVING …...................................................................................................................................................................................2 DRONES...……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...2 EMERGENCY & URGENT COMMUNICATIONS………..………………………………………………………………... 3 ENTRY & EXIT PROCEDURES .......................................................................................................................................... 3 FIRE DEPARTMENT ............................................................................................................................................................ -

DN530 Creative Quad Gate

DN530 Creative Quad Gate Operator Manual Klark Teknik, Klark Industrial Park, Walter Nash Road, Kidderminster. Worcestershire. DY11 7HJ. England. Tel: +44 1562 741515 Fax: +44 1562 745371 Email: [email protected] Website: www.klarkteknik.com DN530 Creative Quad Gate — Operator Manual DOC02-DN530 Issue B — February 2010 © Red Chip Company Ltd. In line with the company’s policy of continual improvement, specifications and function may be subject to change without notice. This Operator Manual was correct at the time of writing. E&OE. IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the product's enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the product. 1 Read these instructions. 11 Only use attachments/accessories specified by the manufacturer. 2 Keep these instructions. 12 Unplug this apparatus during lightning 3 Heed all warnings. storms or when unused for long periods of 4 Follow all instructions. time. 5 Do not use this apparatus near water. 13 Refer all servicing to qualified personnel. Servicing is required when the apparatus 6 Clean only with a dry cloth. has been damaged in any way, such as 7 Do not block any of the ventilation power-supply cord or plug is damaged, openings. Install in accordance with the liquid has been spilled or objects have manufacturer’s instructions. -

How Astronomical Objects Are Named

How Astronomical Objects Are Named Jeanne E. Bishop Westlake Schools Planetarium 24525 Hilliard Road Westlake, Ohio 44145 U.S.A. bishop{at}@wlake.org Sept 2004 Introduction “What, I wonder, would the science of astrono- use of the sky by the societies of At the 1988 meeting in Rich- my be like, if we could not properly discrimi- the people that developed them. However, these different systems mond, Virginia, the Inter- nate among the stars themselves. Without the national Planetarium Society are beyond the scope of this arti- (IPS) released a statement ex- use of unique names, all observatories, both cle; the discussion will be limited plaining and opposing the sell- ancient and modern, would be useful to to the system of constellations ing of star names by private nobody, and the books describing these things used currently by astronomers in business groups. In this state- all countries. As we shall see, the ment I reviewed the official would seem to us to be more like enigmas history of the official constella- methods by which stars are rather than descriptions and explanations.” tions includes contributions and named. Later, at the IPS Exec- – Johannes Hevelius, 1611-1687 innovations of people from utive Council Meeting in 2000, many cultures and countries. there was a positive response to The IAU recognizes 88 constel- the suggestion that as continuing Chair of with the name registered in an ‘important’ lations, all originating in ancient times or the Committee for Astronomical Accuracy, I book “… is a scam. Astronomers don’t recog- during the European age of exploration and prepare a reference article that describes not nize those names. -

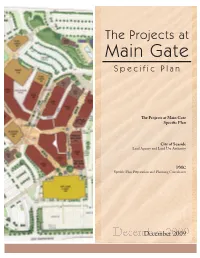

The Projects at Main Gate Specific Plan

The Projects at Main Gate Specific Plan The Projects at Main Gate Specific Plan City of Seaside Lead Agency and Land Use Authority PMC Specific Plan Preparation and Planning Consultants DecemberDecember 200922000099 The Projects at Main Gate Specific Plan PUBLIC REVIEW DRAFT City of Seaside Lead Agency Land Use Authority and Project Sponsor PMC Specific Plan Preparation and Planning Consultants December 2009 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction The Projects at Main Gate Specific Plan (Specific Plan) outlines the future development of approximately 56 acres of the former Fort Ord in the City of Seaside. The Specific Plan is a planning framework document intended to set forth the land uses, circulation, site planning, conceptual building, landscaping, architectural design, and specific development standards and design guidelines for the Specific Plan Area. The intent of the Specific Plan is to encourage investment and coordinated development through a clearly established public commitment to the intensification of the area, and through a clear pattern of land uses that provides investors with a level of certainty regarding the future form and character of development. Taken together, the projects are viewed as a key retail and hospitality development effort that will further implement the City’s long range planning, economic, and redevelopment goals. The City sponsored the preparation of this Specific Plan to develop a Lifestyle Center with a retail center (“The Strand”) hotel/conference center, and a full service spa. The completion of this Specific Plan and accompanying environmental documents will establish a process for development review and approval, leading ultimately to implementation and construction of a well planned and designed retail destination that fits the site and the community’s aspirational needs for a retail center. -

Tillamook County Fair 2021 1 Aug

www.tillamookheadlightherald.com Tillamook County Fair 2021 1 Aug. 11-14, 2021 Tillamook County Headlight Herald 2 2 Tillamook County Fair 2021 www.tillamookheadlightherald.com TILLAMOOK COUNTY FAIRGROUNDS BUILDING NUMBERS LIST 1. West Gate Entry 18. Fair Acres 33. Public Parking A ADMISSION PRICES 2. Entry Lane 19. Open Class Dairy 34. Public Parking B 3. 4-H Dormitory Barn 35. South Horse Adult $ 10.00/day 4. Front Area 20. Courtyard Stage Arena 5. Main Gate Entry 21. Information 36 Vendor RV Season Pass $ 30.00 6. OSU Learning Booth Parking & Garden 22. TLC Stadium Camping Child (6-11) $ 6.00/day 7. Premium 23. Averill Arena 37. Commercial Senior Citizens $ 6.00* Handicap 24. Beer Gardens Exhibitor, Parking 25. Horse Paddocks Superintendent *Thursday Only & 62 and Older 8. Premium Parking 26. 4-H/FFA & Volunteer 9. Carnival Livestock Barn Parking 10. Carnival 27. Pavilion 38. Horse Stables Restrooms 28. Aufdermauer 39. Horse Trailer, 11. Sheriff’s Booth Arena Cattle PARKING PRICES 12. Restaurant Row 29. Farm Machinery Trailer & Demolition 13. Convention Area Public & Handicap Parking $ 5.00/day Derby Center 30. Barn Parking Staging Area 14. Auditorium 31. Reserved Season Pass $ 60.00 (Participants 15. Fair Office Parking Only) Premium Parking $ 15.00/day 16. Main Building 32. Handicap 17. Pioneer Building Parking 40. Race Track Premium Handicap Parking $ 15.00/day 3 map3 www.tillamookheadlightherald.com Tillamook County Fair 2021 3 4 4 Tillamook County Fair 2021 www.tillamookheadlightherald.com Tillamook County Fair Schedule Wednesday -

Estimation the Presence of Heavy Metals and Trace Elements in Indian Herbal Cosmetics by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer

Chakraborty et al Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Development. 2019; 7(5): -60-65 Available online on 15.10.2019 at http://ajprd.com Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Development Open Access to Pharmaceutical and Medical Research © 2013-19, publisher and licensee AJPRD, This is an Open Access article which permits unrestricted non- commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited Open Access Research Article Estimation the Presence of Heavy Metals and Trace Elements in Indian Herbal Cosmetics by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer Chakraborty Krishnasis *, Choudhary Suraj Department of Quality Assurance Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Opposite to Lalbagh Main Gate, Hosur road, Bangalore, India A B S T R A C T Heavy metals are identically Pb, Cd and micronutrients elements like Ca, Mg, Al, Cu and Zn were quantitatively estimated using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS). Similarly, heavy metals such as As and Hg were quantitatively estimated by Hydride Generation Technique i.e. Cold Vapor Atomic Absorption Spectrometry method expending nitrogen as carrier gas in 30 herbal cosmetic preparations available in Indian markets. The results designate that among the toxic heavy metals. In the present study, Arsenic was found significantly well below the permissible limit, but Cd was found above the permissible limit in the all samples. Trace elements like Ca and Mg were found in higher amount than compare to Al, Cu, and Zn. Presence of trace elements can corroborate to be beneficial but existence of toxic heavy metals in such amounts certainly has adverse effects on the consumer health who always take the herbal products in an impression of being safe because of the natural origin. -

Archaeoacoustic Analysis of the Ancient Site of Kanda (Macedonia) Preliminary Results

d va n - A c e d A R S e R s A e a - r c E h C i N n E Advanced Research in Scientific Areas S R c E i F e n N t O i f C i c L A A r U e T a R s I - V December, 1. - 5. 2014 Archaeoacoustic analysis of the ancient site of Kanda (Macedonia) Preliminary results Paolo Debertolis Aristotel Tentov Domagoj Nikolić Department of Medical Sciences Department of IT Lecturer/Applied Technologies University of Trieste, Italy University "St. Kiril i Metodij" Rochester Institute of Technology (*) Project SB Research Group Skopje, Macedonia Dubrovnik, Croatia [email protected] Goran Marjanović Heikki Savolainen Nina Earl Electrical Engineer HSS Production Scientific assistant Project SB Research Group(*) Project SB Research Group(*) Project SB Research Group(*) Belgrade, Serbia Helsinki, Finland United Kingdom 1Abstract — Research was carried out on a geoglyph located in studies researchers of SB Research Group have established that Kanda (Macedonia) by an international team using various ancient sites considered “sacred” have specific natural interdisciplinary methods (astronomy, philosophy, mythology, properties affecting people. These properties make the location mathematics and physics). The research conducted on two “sacred” [3,4,5,6]. occasions in 2014 was undertaken to establish all potential anomalies in the IS, US and EM spectrum with special attention “Sacred sites” are locations which particular groups deem to anomalies common to sacred sites, but as yet unexplained by worthy of veneration. They are typically places of worship and standard physics. are used for spiritual or religious rituals.