Voting Rights in New York 1982-2006, LEP Language Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 1 Before the New York State Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means Committees 2

1 1 BEFORE THE NEW YORK STATE SENATE FINANCE AND ASSEMBLY WAYS AND MEANS COMMITTEES 2 ---------------------------------------------------- 3 JOINT LEGISLATIVE HEARING 4 In the Matter of the 2020-2021 EXECUTIVE BUDGET ON 5 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 6 ---------------------------------------------------- 7 Hearing Room B Legislative Office Building 8 Albany, New York 9 February 13, 2020 9:37 a.m. 10 11 PRESIDING: 12 Senator Liz Krueger Chair, Senate Finance Committee 13 Assemblywoman Helene E. Weinstein 14 Chair, Assembly Ways & Means Committee 15 PRESENT: 16 Senator Pamela Helming Senate Finance Committee (Acting RM) 17 Assemblyman Edward P. Ra 18 Assembly Ways & Means Committee (RM) 19 Senator Anna M. Kaplan Chair, Senate Committee on Commerce, 20 Economic Development and Small Business 21 Assemblyman Robin Schimminger Chair, Assembly Committee on Economic 22 Development, Job Creation, Commerce and Industry 23 Senator Diane J. Savino 24 Chair, Senate Committee on Internet and Technology 2 1 2020-2021 Executive Budget Economic Development 2 2-13-20 3 PRESENT: (Continued) 4 Assemblyman Al Stirpe Chair, Assembly Committee on Small Business 5 Senator Joseph P. Addabbo Jr. 6 Chair, Senate Committee on Racing, Gaming and Wagering 7 Senator James Skoufis 8 Chair, Senate Committee on Investigations and Government Operations 9 Assemblyman Kenneth Zebrowski 10 Chair, Assembly Committee on Governmental Operations 11 Senator John Liu 12 Assemblyman Harvey Epstein 13 Assemblyman Robert Smullen 14 Assemblyman Billy Jones 15 Senator Brad Hoylman 16 Assemblywoman Marianne Buttenschon 17 Assemblyman Christopher S. Friend 18 Senator Luis R. Sepulveda 19 Assemblyman Steve Stern 20 Assemblyman Chris Tague 21 Senator James Tedisco 22 Assemblyman Brian D. Miller 23 Assemblywoman Mathylde Frontus 24 3 1 2020-2021 Executive Budget Economic Development 2 2-13-20 3 PRESENT: (Continued) 4 Senator George M. -

City of New York 2012-2013 Districting Commission

SUBMISSION UNDER SECTION 5 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT (42 U.S.C. § 1973c) CITY OF NEW YORK 2012-2013 DISTRICTING COMMISSION Submission for Preclearance of the Final Districting Plan for the Council of the City of New York Plan Adopted by the Commission: February 6, 2013 Plan Filed with the City Clerk: March 4, 2013 Dated: March 22, 2013 EXPEDITED PRECLEARANCE REQUESTED TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. EXPEDITED CONSIDERATION (28 C.F.R. § 51.34) ................................................. 3 III. THE NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL.............................................................................. 4 IV. THE NEW YORK CITY DISTRICTING COMMISSION ......................................... 4 A. Districting Commission Members ....................................................................... 4 B. Commissioner Training ........................................................................................ 5 C. Public Meetings ..................................................................................................... 6 V. DISTRICTING PROCESS PER CITY CHARTER ..................................................... 7 A. Schedule ................................................................................................................. 7 B. Criteria .................................................................................................................. -

Beyond the Dream Act Latino Leaders' Lack of Legislative

National New York State Institute for Beyond The Dream Act Latino Policy (NiLP) Latino Leaders' Lack 25 West 18th Street of Legislative Imagination at New York, NY 10011 800-590-2516 the Moment They Must Think Big [email protected] By Angelo Falcón www.latinopolicy.org City & State (September 18, 2014) Appears as part of new series by City & State magazine, "The Road to Somos," edited by Gerson Borrero Board of Directors In light of the extreme discontent with President Obama José R. Sánchez among Latinos over his latest delay and broken promises in Chair addressing the issue of deportation relief, how New York Edgar DeJesus State approaches immigrant issues from a legislative Secretary standpoint has become more important and urgent than Israel Colon ever. It was from that perspective that I tuned in with great Treasurer interest to WABC-TV's Tiempo Latino public affairs program Maria Rivera last Sunday, which featured as its guests State Senators José Development Chair Peralta of Queens and José Serrano, who represents parts of Hector Figueroa both the Bronx and Manhattan. Tanya K. Hernandez Angelo Falcón Together, Peralta and President Serrano have served over a quarter of a century in To make a elected office and as donation, prominent Democratic legislators in New York I Mail check or money figured that they would order to the above be a good barometer to address to the order gauge the mood of the of "National Institute Latino political class in for Lastino Policy" regard to Obama's standing as "Deporter-in- Follow us Chief". In many ways, on onTwitter and the national level the Latino community and immigrant advocates now find Angelo's Facebook themselves at a major crossroads, as they come to terms with the limits of Page their reform efforts and grapple with whether there needs to be a fundamental reassessment of their political strategy. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

SOMOS CONFERENCE Saturday, March 9, 2019 Hon

2019 ALBANY SOMOS CONFERENCE Saturday, March 9, 2019 Hon. Carl E. Heastie, Speaker Empire State Plaza Convention Center, Albany, New York Hon. Maritza Davila, Chair MORNING SESSIONS (10:00 AM – 11:45 AM) Equal Access to Driver’s Licenses for All New Yorkers Hearing Room A CO-MODERATORS: Assemblyman Marcos Crespo & Senator Luis Sepúlveda DESCRIPTION: There are 750,000 New Yorkers that are unable to obtain driver’s licenses because of their immigration status. In rural areas throughout the Empire state, public transportation is either infrequent, hard to access, or nonexistent. In these areas, driving becomes a privilege many people don’t think about – providing an avenue to commute to work, pick-up children from school, travel to doctor’s appointments, and fulfill many other essential tasks. If New York were to enact the Driver’s License Access and Privacy Act, it would join twelve states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico in providing access to licenses for undocumented immigrants. Join us for a panel to discuss the need for this legislation and the ongoing Green Light Campaign that brings together community members, leaders and activists with the shared goal of obtaining equal access to driver’s licenses for all New Yorkers. PANELISTS: Eric Gonzalez, District Attorney, Kings County; Emma Kreyche, Statewide Coordinator, Green Light NY Campaign, Worker Justice Center of New York; Nestor Marquez, Westchester Member, Make the Road New York Securing the Future of New York’s Dreamers Hearing Room B CO-MODERATORS: Assemblywoman Carmen De La Rosa & NYC Councilman Francisco Moya DESCRIPTION: In early 2019, the historic José Peralta New York State DREAM Act (S.1250 / A.782) passed through the state legislature. -

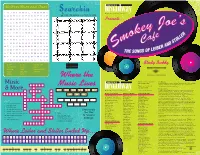

Study Buddy CASSETTE DION ELVIS GUITAR IPOD PHONOGRAPH RADIO RECORD RHYTHM ROCK ROLL Where The

Rhythm, Blues and Clues I V J X F Y R D L Y W D U N H Searchin Michael Presser, Executive Director A Q X R O C K F V K K P D O P Help the musical note find it’s home B L U E S B Y X X F S F G I A Presents… Y C L C N T K F L V V E A D R Y A K O A Z T V E I O D O A G E S W R R T H K J P U P T R O U S I D H S O N W G I I U G N Z E G V A Y V F F F U E N G O P T V N L O T S C G X U Q E H L T G H B E R H O J H D N L P N E C S U W Q B M D W S G Y M Z O B P M R O Y F D G S R W K O F D A X E J X L B M O W Z K B P I D R V X T C B Y W P K P F Y K R Q R E Q F V L T L S G ALBUM BLUES BROADWAY Study Buddy CASSETTE DION ELVIS GUITAR IPOD PHONOGRAPH RADIO RECORD RHYTHM ROCK ROLL Where the 630 Ninth Avenue, Suite 802 Our Mission: Music Inside Broadway is a professional New York City based children’s theatre New York, NY 10036 12 company committed to producing Broadway’s classic musicals in a Music Lives Telephone: 212-245-0710 contemporary light for young audiences. -

1-800-Cuny-Yes Cuny Tv-Channel 75

CUNY EDUCATING LEADERS Pride of New York NEW YORK STATE SENATE Tony Avella Ruben Diaz, Sr. Martin Malave Dilan Adriano Espaillat Simcha Felder Martin Golden Ruth Hassell-Thompson Hunter College Lehman College Brooklyn College Queens College Baruch College John Jay College of Criminal Justice, College of Staten Island Bronx Community College 11th Senate District, Queens 32nd Senate District, Bronx 18th Senate District, Kings 31st Senate District, NY / Bronx 17th Senate District, Kings 22nd Senate District, Kings 36th Senate District, Bronx / Westchester Jeffrey Klein Kevin Parker Jose R. Peralta J. Gustavo Rivera James Sanders Toby A. Stavisky Queens College, CUNY School of Law CUNY Graduate School Queens College CUNY Graduate School Brooklyn College Hunter College, Queens College 34th Senate District, Bronx / Westchester 21st Senate District, Kings 13th Senate District, Queens 33rd Senate District, Bronx 10th Senate District, Queens 16th Senate District, Queens NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY Carmen Arroyo Charles Barron Karl Brabenec James Brennan William Colton Marcos A. Crespo Brian Curran Hostos Community College Hunter College, New York City College of Technology John Jay College of Criminal Justice Baruch College Brooklyn College John Jay College of Criminal Justice CUNY Law School 84th Assembly District, Bronx 60th Assembly District, Kings 98th Assembly District, Rockland / Orange 44th Assembly District, Kings 47th Assembly District, Kings 85th Assembly District, Bronx 21st Assembly District, Nassau Jeffrey Dinowitz Deborah Glick Phillip Goldfeder Pamela Harris Carl Heastie Dov Hikind Ellen C. Jaffee Lehman College Queens College Brooklyn College John Jay College of Criminal Justice Baruch College Brooklyn College, Queens College Brooklyn College 81st Assembly District, Bronx 66th Assembly District, New York 23rd Assembly District, Queens 46th Assembly District, Kings 83rd Assembly District, Bronx 48th Assembly District, Kings 97th Assembly District, Rockland Kimberly Jean-Pierre Ron Kim Guillermo Linares Michael Miller Michael Montesano Francisco Moya Daniel J. -

A Look at the History of the Legislators of Color NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC and ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS

New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus 1917-2014 A Look at the History of the Legislators of Color NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC AND ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS 1917-2014 A Look At The History of The Legislature 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus would like to express a special appreciation to everyone who contributed time, materials and language to this journal. Without their assistance and commitment this would not have been possible. Nicole Jordan, Executive Director Raul Espinal, Legislative Coordinator Nicole Weir, Legislative Intern Adrienne L. Johnson, Office of Assemblywoman Annette Robinson New York Red Book The 1977 Black and Puerto Rican Caucus Journal New York State Library Schomburg Research Center for Black Culture New York State Assembly Editorial Services Amsterdam News 2 DEDICATION: Dear Friends, It is with honor that I present to you this up-to-date chronicle of men and women of color who have served in the New York State Legislature. This book reflects the challenges that resolute men and women of color have addressed and the progress that we have helped New Yorkers achieve over the decades. Since this book was first published in 1977, new legislators of color have arrived in the Senate and Assembly to continue to change the color and improve the function of New York State government. In its 48 years of existence, I am proud to note that the Caucus has grown not only in size but in its diversity. Originally a group that primarily represented the Black population of New York City, the Caucus is now composed of members from across the State representing an even more diverse people. -

Download The

Committee on Health 2019 ANNUAL REPORT New York State Assembly Carl E. Heastie, Speaker Richard N. Gottfried, Chair NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY COMMITTEES: RULES 822 LEGISLATIVE OFFICE BUILDING, ALBANY, NY 12248 HEALTH TEL: 518-455-4941 FAX: 518-455-5939 HIGHER EDUCATION RICHARD N. GOTTFRIED 250 BROADWAY, RM. 2232, NEW YORK, NY 10007 MAJORITY STEERING 75TH ASSEMBLY DISTRICT TEL: 212-312-1492 FAX: 212-312-1494 CHAIR CHAIR E-MAIL: [email protected] MANHATTAN DELEGATION COMMITTEE ON HEALTH December 15, 2019 Carl E. Heastie Speaker of the Assembly Legislative Office Building, Room 932 Albany, New York 12248 Dear Speaker Heastie: I am pleased to submit the 2019 Annual Report of the Assembly Committee on Health. This year the Committee was successful in securing the passage of a host of measures to improve and ensure consistent, quality health care throughout New York State. On behalf of myself and the other members of the Committee, I thank you for your leadership, support and encouragement throughout the Legislative Session. Very truly yours, Richard N. Gottfried Chair Committee on Health New York State Assembly Committee on Health 2019 Annual Report Richard N. Gottfried Chair Albany, New York NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY CARL E. HEASTIE, SPEAKER RICHARD N. GOTTFRIED, CHAIR COMMITTEE ON HEALTH Health Committee Members Majority Minority Thomas Abinanti Jake Ashby Charles Barron Kevin M. Byrne Rodneyse Bichotte Marjorie Byrnes Edward C. Braunstein Andrew Garbarino Kevin A. Cahill David G. McDonough Steven Cymbrowitz Edward P. Ra Jeffrey Dinowitz Andrew P. Raia, Ranking Minority Member Sandra R. Galef Richard N. Gottfried, Chair Aileen M. Gunther Andrew D. -

Voting Rights in New York City: 1982–2006

VOTING RIGHTS IN NEW YORK CITY: 1982–2006 JUAN CARTAGENA* I. INTRODUCTION TO THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT At the time of the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act (VRA) and the continuation of Section 5 coverage to three counties in New York City, the city was at a major crossroads regarding faithful compliance with the mandates of the Act. Just one year earlier in the largest city in the United States, the largest municipal election apparatus in the country was brought to a screeching halt when the federal courts enjoined the Septem- ber mayoral primaries—two days before Election Day—because the city failed to obtain preclearance of new (and discriminatory) city council lines and election district changes.1 The cost of closing down the election was enormous, and a lesson was painfully learned: minority voters knew how to get back to court, the courts would not stand by idly in the face of obvious Section 5 noncompliance and business-as-usual politics would no longer be the same. Weeks later, the Department of Justice (DOJ) would not only of- ficially deny preclearance to the city council plan, but would find that its egregious disregard of the burgeoning African-American and Latino voting strength in the city had a discriminatory purpose and a discriminatory ef- fect.2 In this context, the 1982 extension of Section 5 to parts of New York City should not have seemed so anomalous to a country that continued to * General Counsel, Community Service Society. Esmeralda Simmons of the Center for Law and Social Justice, Medgar Evers College, Margaret Fung of the Asian American Legal Defense and Educa- tion Fund, Jon Greenbaum of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and Debo Adegbile of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund assisted in editing this report. -

Welcome Home

ROBERT M. MORGENTHAU DISTRICT ATTORNEY Upper Manhattan Reentry Task Force WELCOME HOME A Resource Guide for Reentrants and Their Families Harlem Community Justice Center Fair Chance Initiative st 170 East 121 Street New York County District New York, NY 10035 Attorney’s Office 212-360-4131 HOTLINE: 212-335-9435 www.courtinnovation.org HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE If you are returning to Upper Manhattan, welcome home! This guide is intended to support you and your family as you re-integrate into your community. Most of the resources in this guide can be found in Upper Manhattan, although we have included organizations in other parts of New York City as well. If you have a particular interest, you can search the table of contents on page 4 for organizations addressing that interest in the following categories: Staying Stress-Free – Mental Health Services Living a Sober Life – Substance Abuse Services Finding a Job – Employment Services Building Skills – Educational Services Living Strong – Health and Wellness Services Coming Home – Housing Services Connecting with Loved Ones – Family Services Presenting Your Best Self – Clothing Services Getting More Information – Online Resource Guides Special Segment – Section 8 Housing Information You can also search the entire alphabetical listing of organizations, starting on page 9, if you are trying to get information about a specific agency. Please let us know what you think about this guide – your feedback will make it the best resource possible! The Harlem Community Justice Center is located at: 170 East 121 st Street between Lexington and Third Avenues New York, NY 10035 Tel. 212-360-4131 This resource directory can also be located on our website, found at: www.courtinnovation.org. -

Guide to the Petra Allende Papers

Guide to the Petra Allende Papers Petra Allende and Oliver Rios Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños Hunter College, CUNY 2180 Third Avenue @ 119th St., Rm. 120 New York, New York 10035 (212) 396-7877 www.centropr.hunter.cuny.edu Descriptive Summary Resumen descriptivo Creator: Petra Allende Creador: Petra Allende Title: The Petra Allende Papers Título: The Petra Allende Papers Inclusive Dates: 1926-2004 Años extremos: 1926-2004 Bulk Dates: 1970-2001 Período principal: 1970 - 2001 Volume: 17 cubic feet Volumen: 17 pies cúbico Repository: Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Repositorio: Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños Abstract: Community activist and senior citizen Nota de resumen: Defensora de los ciudadanos advocate. This collection documents the history of various envejecientes y activista comunitaria. Esta colección East Harlem/ El Barrio organizations specially those documenta la historia de varias organizaciones del Este dealing with the concerns of senior citizens. Includes de Harlem, conocido como “El Barrio”, especialmente correspondence, articles, minutes, local newspapers, aquellas que tratan con los problemas de los clippings, publications, programs, photographs and envejecientes. Incluye correspondencia, artículos, actas, memorabilia. periódicos locales, recortes de periódico, publicaciones, programas, fotografías y recordatorios. Administrative Information Información administrativa Collection Number: 2003-03