Cortez the Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Sunfly (All) Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 3OH!3 Robin Gibb Don't Trust Me SFKK033-10 (Barry) Islands In The Stream SF278-16 3OH!3 & Katy Perry £1 Fish Man Starstrukk SF286-11 One Pound Fish SF12476 Starstrukk SFKK038-10 10cc 3OH!3 & Kesha Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 My First Kiss SFKK046-03 Dreadlock Holiday SFHT004-12 3SL I'm Mandy SF079-03 Take It Easy SF191-09 I'm Not In Love SF001-09 3T I'm Not In Love SFD701-6-05 Anything FLY032-07 Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Anything SF049-02 Things We Do For Love, The SFMW832-11 3T & Michael Jackson Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Why SF080-11 1910 Fruitgum Company 3T (Wvocal) Simon Says SF028-10 Anything FLY032-15 Simon Says SFG047-10 4 Non Blondes 1927 What's Up SF005-08 Compulsory Hero SFDU03-03 What's Up SFD901-3-14 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-05-10 What's Up SFHH02-09-15 If I Could SFDU09-11 What's Up SFHT006-04 That's When I Think Of You SFID009-04 411, The 1975, The Dumb SF221-12 Chocolate SF326-13 On My Knees SF219-04 City, The SF329-16 Teardrops SF225-06 Love Me SF358-13 5 Seconds Of Summer Robbers SF341-12 Amnesia SF342-12 Somebody Else SF367-13 Don't Stop SF340-17 Sound, The SF361-08 Girls Talk Boys SF366-16 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME SF390-09 Good Girls SF345-07 UGH SF360-09 She Looks So Perfect SF338-05 2 Eivissa She's Kinda Hot SF355-04 Oh La La La SF114-10 Youngblood SF388-08 2 Unlimited 50 Cent No Limit FLY027-05 Candy Shop SF230-10 No Limit SF006-05 Candy Shop SFKK002-09 No Limit SFD901-3-11 In Da -

Rental Song List

Song no Title 1 Syndicate 2 Love Me 3 Vanilla Twilight 4 History 5 Blah Blah Blah 6 Odd One 7 There Goes My Baby 8 Didn't You Know How Much I Love You 9 Rude Boy 10 The Good Life 11 Billionaire 12 Between The Lines 13 He Really Thinks He's Got It 14 If It's Love 15 Mockingbird 16 Your Love 17 Crazy Town 18 You Look Better When I'm Drunk 19 Animal 20 September 21 It's Gonna Be 22 Dynamite 23 Misery 24 Beauty In The World 25 Crow & The Butterfly 26 DJ Got Us Fallin' In Love 27 Touch 28 Someone Else Calling You Baby 29 If I Die Young 30 Just The Way You Are 31 Like A G6 32 Dog Days Are Over 33 Home 34 Little Lion Man 35 Nightmare 36 Hot Tottie 37 Jizzle 38 Lovin Her Was Easier 39 A Little Naughty Is Nice 40 Radioactive 41 One In A Million 42 What's My Name 43 Raise Your Glass 44 Hey Baby (Drop It ToThe Floor) 45 Marry Me 46 1983 47 Right Thru Me 48 Coal Miner's Daughter 49 Maybe 50 S & M 51 For The First Time 52 The Cave 53 Coming Home 54 Fu**in' Perfect 55 Rolling In The Deep 56 Courage 57 You Lie 58 Me & Tennessee 59 Walk Away 60 Diamond Eyes 61 Raining Men 62 I Do 63 Someone Like You 64 Ballad Of Mona Lisa 65 Set Fire To The Rain 66 Just Can't Get Enough 67 I'm A Honky Tonk Girl 68 Give Me Everything 69 Roll Away Your Stone 70 Good Man 71 Make You Feel My Love 72 Catch Me 73 Number One Hit 74 Party Rock Anthem 75 Moves Like Jagger 76 Made In America 77 Drive All Night 78 God Gave Me You 79 Northern Girl 80 The Kind You Can't Afford 81 Nasty 82 Criminal 83 Sexy & I Know It 84 Drowning Again 85 Buss It Wide Open 86 Saturday Night 87 Pumped -

Title 10 Years Beautiful Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs More Than This

M & M MUSIC Title Title 10 Years 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Beautiful She Got It Wasteland 20 Fingers 10,000 Maniacs Short Dick Man More Than This 21st Century Girls Trouble Me 21st Century Girls 100 Proof Aged In Soul 2Play & Thomes Jules & Jucxi D Somebody's Been Sleeping Careless Whisper 10Cc 3 A M Donna Busted Dreadlock Holiday 3 Doors Down I'm Mandy Away From The Sun I'm Not In Love Be Like That Rubber Bullets Behind Those Eyes 112 Better Life It's Over Now Citizen Soldier Peaches & Cream Duck & Run Right Here For You Every Time You Go U Already Know Here By Me 112 & Ludacris Here Without You Hot & Wet It's Not My Time 12 Gauge Kryptonite Dunkie Butt Landing In London 12 Stones Let Me Be Myself We Are One Let Me Go 1910 Fruitgum Co Live For Today Simon Says Loser 2 Live Crew Road I'm On Doo Wah Diddy So I Need You Me So Horny When I'm Gone We Want Some P-Y When You're Young 2 Pac 3 Of A Kind California Love Baby Cakes Until The End Of Time Ikaw Ay Bayani 2 Pac & Eminem 3 Of Hearts One Day At A Time Love Is Enough 2 Pac & Notorious B.I.G. 30 Seconds To Mars Runnin (Dying To Live) Kill 2 Pistols & Ray J 311 You Know Me All Mixed Up Song List Generator® Printed 12/7/2012 Page 1 of 410 Licensed to Melissa Ben M & M MUSIC Title Title 311 411 Amber Teardrops Beyond The Grey Sky 44 Creatures (For A While) When Your Heart Stops Beating Don't Tread On Me 5 6 7 8 First Straw Steps Hey You 50 Cent Love Song 21 Questions 38 Special Amusement Park Caught Up In You Best Friend Fantasy Girl Candy Shop Hold On Loosely Disco Inferno If I'd Been -

General Songs Canapes/Dinner

Canapes/Dinner Fire & Rain – James Taylor Flake – Jack Johnson Flame Trees – Cold Chisel Deep Water – Richard Clapton I’m On Fire – Bruce Springsteen Good Luck Charm – Elvis Rocket Man – Elton John Hotel California – The Eagles These Days – Powderfinger My Baby – Cold Chisel The Weight – The Band Drive – Incubus Peaceful Easy Feelin’ – The Eagles Something So Strong – Crowded House Throw Your Arms Around Me – Hunters Stuck in the Middle – Stealers Wheel Father & Son – Cat Stevens Bright Lights – Matchbox 20 Wicked Game – Chris Isaac The Joker – Steve Miller Band Why Georgia – John Mayer Ticket To Tide – The Beatles My Kind of Scene – Powderfinger To Her Door – Paul Kelly Time After Time – Cyndi Laupe Diamonds on the Inside – Ben Harper Babylon – David Gray Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Learn to Fly – Foo Fighters Everything – Michael Buble I’m Yours – Jason Mraz Hey Soul Sister – Train Fast Car – Tracy Chapman How Long Will I Love You – Ellie Goulding Reminiscing – Little River Band Rodeo Clowns – Jack Johnson General Songs Bonfire Heart – James Blunt Can’t Take My Eyes Off You – Frankie Vallie Budapest – George Ezra Ho Hey - Lumineers Delilah – Plain White Tees Bright Side of The Road – Van Morrison I’m Not The only One – Sam Smith Mr. Jones – Counting Crows Periscopes – The Beautiful Girls Galway Girl – Steve Earl Steal My Kisses – Ben Harper Burn Your Name - Powderfinger The Horses – Daryl Braithwaite Sultans of Swing – Dire Straits Valerie – Amy Winehouse Proud Mary – Creedence Clearwater Don’t Want to Miss A Thing - Aerosmith Wagon -

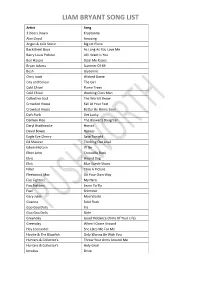

Liam Bryant Song List

LIAM BRYANT SONG LIST Artist Song 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Alex Lloyd Amazing Angus & Julia Stone Big Jet Plane Backstreet Boys As Long As You Love Me Barry Louis Polistar All I Want Is You Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bryan Adams Summer Of 69 Bush Glycerine Chris Isaak Wicked Game City and Colour The Girl Cold Chisel Flame Trees Cold Chisel Working Class Man Collective Soul The World I Know Crowded House Fall At Your Feet Crowded House Better Be Home Soon Daft Punk Get Lucky Damien Rice The Blower's Daughter Daryl Braithwaite Horses David Bowie Heroes Eagle Eye Cherry Save Tonight Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Edwin McCain I'll Be Elton John Crocodile Rock Elvis Hound Dog Elvis Blue Suede Shoes Filter Take A Picture Fleetwood Mac Go Your Own Way Foo Fighters My Hero Foo Fighters Learn To Fly Fuel Shimmer Gary Jules Mad World Goanna Solid Rock Goo Goo Dolls Iris Goo Goo Dolls Slide Greenday Good Riddance (Time Of Your Life) Greenday When I Come Around Hey Leonardo! She Likes Me For Me Hootie & The Blowfish Only Wanna Be With You Hunters & Collector's Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collector's Holy Grail Incubus Drive LIAM BRYANT SONG LIST Inner Circle Sweat Jack Johnson Flake Jack Johnson Sitting, Waiting, Wishing Jeff Buckley Halleluiah Jennifer Paige Crush Jimmy Buffett Escape Pina Colada John Legend All Of Me John Lennon Imagine Johnny Cash Ring of Fire Jose Gonzalez Heartbeats Kenny Rogers The Gambler Kings Of Leon Use Somebody Lauryn Hill Can't Take My Eyes Off You Lenny Kravitz Again Leonardo's Bride Even When I'm Sleeping Lifehouse -

Faultlines 3-13-13

Fault Lines A Nomad Filmmaker’s Journal Memoir by John Knoop 1 Fault Lines A Nomad Filmmaker’s Journal Copyright 2012 John Knoop 2 I’m on the home stretch. Ready for the Reaper, though not expecting him just yet. Still eager to savor the human comedy along with memories of many great adventures. I’ve been sitting here looking out at the San Francisco Bay from my place on the ridge-top in El Cerrito, trying to figure out how to tell my story. I’ve had a full life and the trade-off is that I must live in a wreaked body that wakes me at dawn every day with waves of spasms and soreness. I know I’m lucky that I still have a body that walks and a story to tell. Maybe the challenge will prevent me from mourning over the decay of our republic and keep my mind moving even if my body can’t follow at its old pace. There may not be a publisher ready to take a chance on an oddly structured memoir by a non-celebrity but I hope to publish mine so I can give copies to my grandchildren. First I must write it. I hobble into the kitchen and heat some water in a battered saucepan to pour over a spoonful of Turkish grind. I’ve been making coffee this way since living in Bali years ago while I shot a film there. Maybe a toke of hash to open the memory bin, which contains a kaleidoscope of events from both war and peace. -

Artist Title 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK of YOU 1927

Artist Title 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK OF YOU 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 1927 IF I COULD 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE 3OH3 DON'T TRUST ME 3OH3, KESHA BLAH BLAH BLAH 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEY EVERYBODY 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT JUST A LIL' BIT A HA TAKE ON ME A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA ANGEL EYES ABBA CHIQUITA ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR ABBA HEAD OVER HEELS ABBA HONEY HONEY ABBA LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME ABBA MAMMA MIA ABBA SO LONG ABBA SUPER TROUPER ABBA TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC ABBA WATERLOO ABBA WINNER TAKES IT ALL ABBA AS GOOD AS NEW ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DAY BEFORE YOU CAME ABBA FERNANDO ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA I HAVE A DREAM ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY ABBA NAME OF THE GAME ABBA ONE OF US ABBA RING RING ABBA ROCK ME ABBA SOS ABBA SUMMER NIGHT CITY ABBA VOULEZ VOUS ABC LOOK OF LOVE ACDC LONG WAY TO THE TOP ACDC THUNDERSTRUCK AC-DC JAILBREAK AC-DC WHOLE LOTTA ROSIE AC-DC ROCK N ROLL TRAIN AC-DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC-DC BACK IN BLACK AC-DC FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK AC-DC HEATSEEKER AC-DC HELL'S BELLS AC-DC HIGHWAY TO HELL AC-DC JACK, THE AC-DC LET THERE BE ROCK AC-DC LONG WAY TO THE TOP AC-DC STIFF UPPER LIP AC-DC THUNDERSTRUCK AC-DC TNT AC-DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE OF BASE THE SIGN ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ADAM HARVEY BETTER THAN THIS ADAM LAMBERT IF I HAD YOU ADAM LAMBERT TIME FOR MIRACLES ADELE HELLO AEROSMITH -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

A Beat for You Pseudo Echo a Day in the Life the Beatles a Girl Like

A Beat For You Pseudo Echo A Day In The Life The Beatles A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins A Good Heart Feargal Sharkey A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bryan Ferry A Kind Of Magic Queen A Little Less Conversation Elvis vs JXL A Little Ray of Sunshine Axiom A Matter of Trust Billy Joel A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Touch Of Paradise John Farnham A Town Called Malice The Jam A View To A Kill Duran Duran A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum Abacab Genesis About A Girl Nirvana Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Absolute Beginners David Bowie Absolutely Fabulous Pet Shop Boys Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Adam's Song Blink 182 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Adventure of a Lifetime Coldplay Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers Affirmation Savage Garden Africa Toto After Midnight Eric Clapton Afterglow INXS Agadoo Black Lace Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) Phil Collins Against The Wind Bob Seger Age of Reason John Farnham Ahead of Myself Jamie Lawson Ain't No Doubt Jimmy Nail Ain't No Mountain High Enough Jimmy Barnes Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine The Rockmelons feat. Deni Hines Alive Pearl Jam Alive And Kicking Simple Minds All About Soul Billy Joel All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All By Myself Eric Carmen All Fired Up Pat Benatar All For Love Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart & Sting All I Do Daryl Braithwaite All I Need Is A Miracle Mike & The Mechanics All I Wanna Do Sheryl Crow All I Wanna Do Is Make Love To You Heart All I Want -

2017 Songbooks (Autosaved).Xlsx

Song Title Artist Code 1 Mortin Solveig & Same White 21412 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 20606 1999 Prince 20517 #9 dream John Lennon 8417 1 + 1 Beyonce 9298 1 2 3 One Two Three Len Barry 4616 1 2 step Missy Elliot 7538 1 Thing Amerie 20018 1, 2 Step Ciara ft. Missy Elliott 20125 10 Million People Example 10203 100 Years Five For Fighting 4453 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 6117 1000 miles away Hoodoo Gurus 7921 1000 stars natalie bathing 8588 12:51 Strokes 4329 15 FEET OF SNOW Johnny Diesel 9015 17 Forever metro station 8699 18 and life skid row 7664 18 Till i die Bryan Adams 8065 1959 Lee Kernagan 9145 1973 James Blunt 8159 1983 Neon Trees 9216 2 Become 1 Jewel 4454 2 FACED LOUISE 8973 2 hearts Kylie Minogue 8206 20 good reasons thirsty merc 9696 21 Guns Greenday 8643 21 questions 50 Cent 9407 21st century breakdown Greenday 8718 21st century girl willow smith 9204 22 Taylor Swift 9933 22 (twenty-two) Lily Allen 8700 22 steps damien leith 8161 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 21533 3 (one two three) Britney Spears 8668 3 am Matchbox 20 3861 3 words cheryl cole f. will 8747 4 ever Veronicas 7494 4 Minutes Madonna & JT 8284 4,003,221 Tears From Now Judy Stone 20347 45 Shinedown 4330 48 Special Suzi Quattro 9756 4TH OF JULY SHOOTER JENNINGS 21195 5, 6, 7, 8. steps 8789 50 50 Lemar 20381 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 1805 50 ways to say Goodbye Train 9873 500 miles Proclaimers 7209 6 WORDS WRETCH 32 21068 7 11 BEYONCE 21041 7 Days Craig David 2704 7 things Miley Cyrus 8467 8675309 Jenny Tommy Tutone 1807 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 20210 99 Red Balloons Nena -

A Beat for You Pseudo Echo a Day in the Life the Beatles a Girl Like

A Beat For You Pseudo Echo A Day In The Life The Beatles A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins A Good Heart Feargal Sharkey A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bryan Ferry A Kind Of Magic Queen A Little Less Conversation Elvis vs JXL A Little Ray of Sunshine Axiom A Matter of Trust Billy Joel A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Touch Of Paradise John Farnham A Town Called Malice The Jam A View To A Kill Duran Duran A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum Abacab Genesis About A Girl Nirvana Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Absolute Beginners David Bowie Absolutely Fabulous Pet Shop Boys Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Adam's Song Blink 182 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Adventure of a Lifetime Coldplay Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers Affirmation Savage Garden Africa Toto After Midnight Eric Clapton Afterglow INXS Agadoo Black Lace Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) Phil Collins Against The Wind Bob Seger Age of Reason John Farnham Ahead of Myself Jamie Lawson Ain't No Doubt Jimmy Nail Ain't No Mountain High Enough Jimmy Barnes Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine The Rockmelons feat. Deni Hines Alive Pearl Jam Alive And Kicking Simple Minds All About Soul Billy Joel All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All By Myself Eric Carmen All Fired Up Pat Benatar All For Love Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart & Sting All I Do Daryl Braithwaite All I Need Is A Miracle Mike & The Mechanics All I Wanna Do Sheryl Crow All I Wanna Do Is Make Love To You Heart All I Want