Weirding Utopia for the Anthropocene: Hope, Un/Home and the Uncanny in Annihilation and the City We Became

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N.K. Jemisin in the City We Became, the Award-Winning Science Fiction Writer Keeps Breaking New Ground P

Featuring 407 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 6 | 15 MARCH 2020 REVIEWS N.K. Jemisin In The City We Became, the award-winning science fiction writer keeps breaking new ground p. 14 Also in the issue: Kevin Nguyen, Victoria James, Jessica Kim, and more from the editor’s desk: Great Escapes Through Reading Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # March is the dreariest month. We know that spring is around the cor- Chief Executive Officer ner, but…it can be a long time coming. If you’re fortunate, you might escape MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] to a Florida beach or some other far-flung destination for rejuvenation. For Editor-in-Chief the rest of us, spring break may come in the form of a book that transports TOM BEER [email protected] us elsewhere, indelibly rendered through prose. Here are five titles, new or Vice President of Marketing coming soon, that the travel agent in me would like to recommend. But be SARAH KALINA [email protected] forewarned: There is frequently trouble in paradise. Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU Saint X by Alexis Schaitkin (Celadon Books, Feb. 18): The title refers [email protected] to the fictional Caribbean island where the Thomas family is on a vacation Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK at an evocatively described resort—“the long drive lined with perfectly ver- [email protected] Tom Beer tical palm trees,” “the beach where lounge chairs are arranged in a parab- Children’s Editor VICKY SMITH ola,” the scents of “frangipani and coconut sunscreen and the mild saline of [email protected] equatorial ocean.” Alas, this family vacation does not end well, forever altering the lives of Claire Young Adult Editor LAURA SIMEON Thomas, age 7 at the time, and Clive Richardson, an employee at the resort. -

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

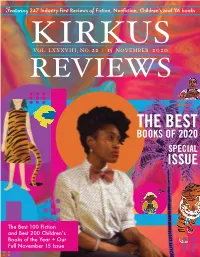

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

This Bookshelf: 2020 Books Links to All Steve Hopkins' Bookshelves

This Bookshelf: 2020 Books Links to All Steve Hopkins’ Bookshelves Web Page PDF/epub/Searchable Link to Latest Book Reviews: Book Reviews Blog Links to Current Bookshelf: Pending and Read 2020 Books 2020 Books Links to 549 Books Read or Skipped in 2020 2020 Bookshelf 2020 Bookshelf Links to All Books from 1999 All Books Authors A through All Books Authors A through through 2020 Authors A-G G G Links to All Books from 1999 through 2020 Authors H-M All Books Authors H All Books Authors H through M through M Links to All Books from 1999 All Books Authors N through All Books Authors N through through 2020 Authors N-Z Z Z Book of Books: An ebook of Book of Books books read, reviewed or skipped from 1999 through 2020 This web page lists all 360 books reviewed by Steve Hopkins at http://bkrev.blogspot.com during 2020 as well as 189 books relegated to the Shelf of Ennui. You can click on the title of a book or on the picture of any jacket cover to jump to amazon.com where you can purchase a copy of any book on this shelf. Key to Ratings: I love it ***** I like it **** It’s OK *** I don’t like it ** I hate it * Click on Title (Click on Link Blog Picture to to purchase at Author(s) Rating Comments Date Purchase at amazon.com) amazon.com Endless. For an immersive mediation on war, read Salar Abdoh’s novel titled, Out of Mesopotamia. From the perspective of protagonist Saleh, a journalist, we struggle to make sense of those who are engaged in what Out of seems like endless war. -

Bookazinebits April 9Th, 2020

BookazineBits April 9th, 2020 On the cover of the NYT Book Review for 4/12/20 American Conservatism: Reclaiming an Intellectual Tradition by Andrew Bacevich (ISBN 9781598536560 $29.95) As American conservatism stands at a crossroads, Andrew Bacevich presents a groundbreaking collection of mainstream conservative writings since 1900, redefining a tradition whose ideas, debates, and defiance have profoundly shaped our national life. The ideas that animate mainstream American conservatism have long been misunderstood or belittled. Here, in a sweeping gathering of 45 essential conservative writers, editor Andrew Bacevich surveys the core currents of conservative thought in the United States since 1900: the importance of tradition, the value of familial and local ties, the mounting of resistance to an ever-expanding state, the opposition to collectivist utopias and other forms of tyranny abroad, and the necessity of free markets and economic growth to sustain individual liberties and prosperity. Bacevich reveals that American conservativism has hardly been a monolithic entity over the last 120 years. Instead, conservative thought has developed through fierce internal contention and debate about fundamental questions about who we are as a people and as a nation. On display here are impassioned arguments about bedrock beliefs: Andrew Sullivan’s influential conservative case for same-sex marriage before the prospect was widely taken seriously is joined by Antonin Scalia’s dissent in the Obergefell case before the Supreme Court, which made same-sex marriage the law of the land. Writings by isolationists stand side by side with neoconservative calls for foreign intervention; well- known names such as Charles Beard, Ronald Reagan, and William F. -

The City We Became / N.K

Copyright This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental. Copyright © 2020 by N. K. Jemisin The prologue was originally published in a slightly different version as “The City Born Great” on Tor.com, copyright © 2016 by N. K. Jemisin Cover design by Lauren Panepinto Cover photos by Arcangel and Shutterstock Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc. Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Orbit Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10104 orbitbooks.net First Edition: March 2020 Simultaneously published in Great Britain by Orbit Orbit is an imprint of Hachette Book Group. The Orbit name and logo are trademarks of Little, Brown Book Group Limited. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. -

Justice. Transformation. Education. Reimagining the Dance Ecology

1 Justice. Transformation. Education. Reimagining the dance ecology. MARCH 17–20, 2021 @DanceNYC #DanceSymp 2 FUNDERS SPONSORS Leadership support is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Howard Gilman Foundation. The Symposium is also supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council, from the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and from the National Endowment for the Arts. Jody Gottfried Arnhold is Dance/NYC’s 2021 Symposium Lead Dance Advocate. Subsidies for the education and dance worker ticket tiers are made possible by the Arnhold Foundation. Con Edison is Dance/NYC’s 2021 Symposium Lead Corporate Sponsor. 3 4 Strengthening Communities WE PROUDLY SUPPORT Dance/NYC AND ITS 2021 SYMPOSIUM. Everything Matters 5 PARTNERS JUSTICE, EQUITY & INCLUSION PARTNERS Dance/NYC’s approach to increasing justice, equity, and inclusion in dance is grounded in collaboration. It has established partnerships with colleague arts service organizations that are mission-focused on increasing racial justice, inclusion and access for disabled people, and/or integration of immigrants into arts and culture. 6 7 MISSION & VALUES Dance/NYC’s mission is to promote the knowledge, appreciation, practice, and performance of dance in the metropolitan New York City area. It embeds values of justice, equity, and inclusion into all aspects of the organization. Dance/NYC believes the dance ecology must itself be just, equitable, and inclusive to meaningfully contribute to social progress, and envisions a dance ecology wherein power, funding, opportunities, conduct, and impacts are fair for all artists, cultural workers, and audiences. -

Who We Are: Visualizing Nyc By

“I Count Because” sign used at a New York City Council press conference, April 23, 2019 Photograph by John McCarten; Courtesy John McCarten / New York City Council WHO WE ARE: VISUALIZING NYC BY THE NUMBERS OPENS NOVEMBER 22 AT MUSEUM OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK New Multimedia Exhibition Examines the Importance and Impact of the Census-- How We Are Counted and What’s At Stake Crowdsourced Data Visualization Experiments Led by Giorgia Lupi and Ekene Ijeoma, Conducted and Featured As Part of Show On View through August 23 Press Preview: November 19, 10 AM-12 PM (NEW YORK, NY – January 2020) – Museum of the City of New York today revealed details of its major fall exhibition, Who We Are: Visualizing NYC By The Numbers. Presented in anticipation of the 2020 Census, the multimedia show features works by cutting edge contemporary artists, designers, and researchers--alongside rare archival objects and documents, maps and photographs--and explores, celebrates, and underscores the power of the population count and demographics in understanding the past, present, and potential future of New York City. Who We Are is on view through August 23rd, 2020. Census data has long been a tool to better understand New York City and its dense, chaotic mosaic of some eight and a half million inhabitants. Who We Are poses provocative questions about how the data collected about us as individuals reflects who we are as a society, and presents the data in novel ways that transcend mere reportage. According to Whitney Donhauser, Ronay Menschel Director and President of the Museum of the City of New York, “We are presenting Who We Are as a way to highlight the importance of the upcoming census – including what’s at stake in terms of ensuring fair political representation and sufficient funding for education, infrastructure, and social programs. -

2021 Summer Reading

2021 Summer Reading LMHS Library / English Department A note to students and their families: We have tried to include a variety of topics, genres, and styles on this list so that students will find books that they enjoy. Some of the titles were suggested by students, some are award winners, and many are highly acclaimed recent releases. Parents may want to assist their child in picking out appropriate books in consideration of their family’s values and children’s interests. Eliza and Her Monsters by Francesca Zappia Realistic Fiction *2022 Nutmeg Nominee Eighteen-year-old Eliza Mirk is the anonymous creator of the wildly popular webcomic Monstrous Sea, but when a new boy at school tempts her to live a life offline, everything she’s worked for begins to crumble. In the real world, Eliza Mirk is shy, weird, and friendless. Online, Eliza is LadyConstellation, anonymous creator of a popular webcomic called Monstrous Sea. With millions of followers and fans throughout the world, Eliza’s persona is popular. Eliza can’t imagine enjoying the real world as much as she loves her digital community. Then Wallace Warland transfers to her school and Eliza begins to wonder if a life offline might be worthwhile. But when Eliza’s secret is accidentally shared with the world, everything she’s built—her story, her relationship with Wallace, and even her sanity—begins to fall apart. The Racers by Neal Bascomb Narrative Nonfiction In the years before World War II, Adolf Hitler wanted to prove the greatness of the Third Reich in everything from track and field to motorsports. -

Anthony Veasna So Remembered Holmes Chan Hong Kong Spirit Richard Heydarian Asian Revolutionaries Anthony Tao Hutong Secrets

Anthony Veasna So remembered ASIAN LITERATURE FEBRUARY–APRIL 2021 Holmes Chan Anthony Tao Hong Kong spirit Hutong secrets Richard Heydarian Tse Wei Lim Asian revolutionaries Hawker culture 32 9 772016 012803 VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY–APRIL 2021 HISTORY 3 Thomas A. Bass Kissinger and Ellsberg in Vietnam TAIWAN 7 Michael Reilly Between two whales POETRY 8 Maw Shein Win ‘Phone booth’, ‘Shops’, ‘Restaurant’, ‘Factory’, ‘Eggs’, ‘Huts’ INTERVIEW 9 Andrew Quilty Mullah Abdul Rahman, Taliban commander NOTEBOOK 12 Yuen Chan In China’s grip ASIA 13 Richard Heydarian Underground Asia: Global Revolutionaries and the Assault on Empire by Tim Harper MYANMAR 14 David Scott Mathieson The Burmese Labyrinth: A History of the Rohingya Tragedy by Carlos Sardina Galache HONG KONG 15 Holmes Chan Defiance: Photographic Documentary of Hong Kong’s Awakening; Voices JOURNALISM 16 Martin Stuart-Fox You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War by Elizabeth Becker CHINA 18 Anne Stevenson-Yang Anxious China: Inner Revolution and Politics of Psychotherapy by Li Zhang AUSTRALIA 19 Jeff Sparrow The Carbon Club: How a Network of Influential Climate Sceptics, Politicians and Business Leaders Fought to Control Australia’s Climate Policy by Marian Wilkinson MALAYSIA 20 Charles Brophy Automation and the Future of Work by Aaron Benanav; Work in an Evolving Malaysia: The State of Households 2020, Part II by Khazanah Research Institute RELIGION 21 Christopher G. Moore Finding the Heart Sutra; Guided by a Magician, an Art Collector and Buddhist Sages from -

Season 3, Episode 14: Who Made Rebecca the Mascot for Fall

Season 3, Episode 14: Who Made Rebecca the Mascot for Fall Reading + Our Favorite Cookbooks Monday, November 2, 2020 • 48:50 Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:10 Hey readers, welcome to the Currently Reading Podcast. We are bookish best friends who spend time every week talking about the books that we read recently. And as you know, we won't shy away from those strong opinions. So get ready. Kaytee Cobb 00:23 We are light on the chitchat, heavy on the book talk, and our descriptions will always be spoiler free. We'll discuss our current reads a bookish deep dive, and then we'll press books into your hands. Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:33 I'm Meredith Monday Schwartz, a mom of four and full time CEO living in Austin, Texas. And sometimes my strong book opinions are stronger than others. Kaytee Cobb 00:43 And I'm Kaytee Cobb, a homeschooling mom of four living in New Mexico. And I love taking a morning walk with an audio book in my ears. This is episode number 14 of season three. And we're so glad you're here. Meredith Monday Schwartz 00:53 Oh, we are so glad to be here. Kaytee, we both have had a busy week. And I know we've both been really looking forward to talking today. Kaytee Cobb 01:01 Yes, I needed some Meredith time for sure. All right, so this is our first episode of November, which means that we get to get started today with our friends at Book of the Month, the only paying advertiser we have for the show, and we get to talk about why we love them. -

NK Jemisin Transcript

* * * * * This is being provided in a rough-draft format. Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) is provided in order to facilitate communication accessibility and may not be a totally verbatim record of the proceedings * * * * * >> Good evening from New York City. Thank you for being with us. I am the curator of the moving image and recorded sound division at the Center of Color and Black Culture. A research center at the New York public library dedicated to the collection, preservation and interpretation of materials focused on the global black experiences. We collect what the founding curator and collector named the vindicating evidences of black history and culture. I am a documentary filmmaker and a 2016 member of the academy motion picture and sciences whose work have been collected by the library. I have the distinct pleasure of introducing tonight's conversation with three time Hugo award winning author N.K. Jemisin and her cousin, K. Kamau Bell. The reason we are here tonight in conversation is the newest book "The City we Became" the first of a new trilogy series in New York City. The book is available for purchase through the library's shop. Not only will you purchasing one of the best books of 2020 but proceeds from your purchase go to benefit the New York public library. The other reason we are here is Nora's book "The Fifth Season" the first book in her previous trilogy is on our list of the 1125 books we love. That list which we released earlier this year celebrates the library's 125th anniversary by honoring titles from the past 125 years that made us fall in love with reading. -

Adult Fiction Nonfiction

Akashic Books Rights List Autumn 2020 ADULT FICTION Out of Mesopotamia a novel by Salar abdoh Speculative Los Angeles edited by deniSe hamilton (featuring: CharleS yu, aimee bender, ben h. WinterS, and more) The Five Books of (Robert) Moses an epiC novel by arthur nerSeSian Creatures of Passage a novel by moroWa yejidé The Nicotine Chronicles edited by lee Child (featuring: eriC bogoSian, joyCe Carol oateS, Jonathan ameS, hannah tinti, and more) Black Lotus and Black Lotus 2: The Vow tWo Crime fiCtion novellaS by K’Wan NONFICTION Face: One Square Foot of Skin by juStine bateman (World engliSh only) Unstrung: Rants and Stories of a Noise Guitarist by marC ribot Akashic Books | Autumn 2020 | Featured Titles Out of Mesopotamia a novel by Salar Abdoh Informed by firsthand experience on the battlefronts of Iraq and Syria, Abdoh captures the horror, confusion, and absurdity of combat from a seldom- glimpsed perspective that expands our understanding of the war novel. BOOK DETAILS: 1 September 2020, 256 pages; fiction/literature COMP TITLES: The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien; Redeployment by Phil Klay; The Association of Small Bombs by Karan Mahajan HIGHLIGHTS: Tehran at Twilight, Salar Abdoh’s previous novel was licensed into: Arabic: Sefsafa Culture & Publishing; Armenian: Antares; Lithuanian: Versus Aureus; Malaysian: Buki Fix; Polish: Sonia Draga; Turkish: Matbuat “For many Americans, the conflicts in Syria and Iraq have become abstractions, separated from our lives by geographic as well as psychic boundaries. Abdoh collapses these boundaries, presenting a disjointed reality in which war and everyday life are inextricably entwined . [The novel shines] a brilliant, feverish light on the nature of not only modern war but all war, and even of life itself.” —New York Times Book Review (Editors’ Choice) “A superb pressure cooker of a novel .