Ecological Assessment of a Proposed Structure Plan for 790C Hot Water Beach Road, Whenuakite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Guide to Camping on the Coromandel Places to Stay, the Rules and Handy Tips for Visitors 2013

The complete guide to camping on the Coromandel Places to stay, the rules and handy tips for visitors 2013 www.tcdc.govt.nz/camping or www.thecoromandel.com Contents 4 Where to stay (paid campgrounds) Where can I camp? See our list of campsites and contact information for bookings. For more on camping in New Zealand visit www.camping.org.nz or one of our information centres. 6-8 DOC Campgrounds DOC – the Department of Conservation – provides paid campgrounds. See details on these pages. 9 DOC Freedom Camping Policy A quick guide to the DOC freedom camping policy. 10-11 TCDC Freedom Camping sites and guidelines If you are not in a self-contained vehicle you must not camp overnight outside of paid campgrounds. Don’t risk a $200 fine as it could ruin your holiday! Read our important guidelines on where you can and cannot park overnight in a self-contained campervan on these pages. 12 Freedom Camping Prohibited Areas Don’t risk a $200 fine. Be sure you read the signage and do not park overnight in a prohibited area. 2 www.tcdc.govt.nz/camping 13-14 What to do with your rubbish and recycling Drop your recyclables off at a recycling centre as you travel. We’ve listed your nearest Refuse Transfer Station and provided a map for where to find them. 15-16 Public toilets and dump stations Camping our way is not using the roadside as a toilet. Read these pages for locations of public toilets and dump stations where you can empty your campervan wastewater. -

TCDC Camping Brochure 2018 WEB

The complete guide to camping on the Coromandel Places to stay, the rules and handy tips for visitors www.tcdc.govt.nz/camping www.thecoromandel.com Contents 4 Where to stay (paid campgrounds) Where can I camp? See our list of campsites and contact information for bookings. For more on camping in New Zealand visit www.camping.org.nz 6-8 DOC Campgrounds Details on where the Department of Conservation 16-17 Public toilets and provides paid campgrounds. dump stations 9 DOC Freedom Camping Policy Read these pages for locations of public toilets Details on locations where DOC has prohibited or and dump stations where you can empty your restricted freedom camping. campervan wastewater. 10-12 TCDC Freedom Camping Guidelines 18 Coromandel Road Map We welcome responsible freedom camping. Don’t Roads in the Coromandel can be winding, narrow risk a $200 fine by not following the rules and and there are quite a few one-lane bridges. There reading the signage where freedom camping is can be limits on where you can take a rental vehicle, allowed or prohibited. Freedom camping is only so check with your rental company. permitted in Thames-Coromandel District in certified self-contained vehicles. 19 Information Centres Visit our seven information centres or check out 14-15 What to do with your rubbish www.thecoromandel.com for ideas on what to do, and recycling what to see and how to get there. Drop your rubbish and recycling off at our Refuse Transfer Stations or rubbish compactors. We’ve 20 Contact us listed the locations and provided a map showing Get in touch if you have where they are. -

Coromandel Town Whitianga Hahei/Hotwater Tairua Pauanui Whangamata Waihi Paeroa

Discover that HOMEGROWN in ~ THE COROMANDEL good for your soul Produce, Restaurants, Cafes & Arts moment OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE REFER TO CENTRE FOLDOUT www.thecoromandel.com Hauraki Rail Trail, Karangahake Gorge KEY Marine Reserve Walks Golf Course Gold Heritage Fishing Information Centres Surfing Cycleway Airports Kauri Heritage Camping CAPE COLVILLE Fletcher Bay PORT JACKSON COASTAL WALKWAY Stony Bay MOEHAU RANGE Sandy Bay Fantail Bay PORT CHARLES HAURAKI GULF Waikawau Bay Otautu Bay COLVILLE Amodeo Bay Kennedy Bay Papa Aroha NEW CHUM BEACH KUAOTUNU Otama Shelly Beach MATARANGI BAY Beach WHANGAPOUA BEACH Long Bay Opito Bay COROMANDEL Coromandel Harbour To Auckland TOWN Waitaia Bay PASSENGER FERRY Te Kouma Te Kouma Harbour WHITIANGA Mercury Bay Manaia Harbour Manaia 309 Cooks Marine Reserve Kauris Beach Ferry CATHEDRAL COVE Landing HAHEI COROMANDEL RANGE Waikawau HOT WATER COROGLEN BEACH 25 WHENUAKITE Orere 25 Point TAPU Sailors Grave Rangihau Square Valley Te Karo Bay WAIOMU Kauri TE PURU TAIRUA To Auckland Pinnacles Broken PAUANUI 70km KAIAUA Hut Hills Hikuai DOC PINNACLES Puketui Tararu Info WALK Shorebird Coast Centre Slipper Island 1 FIRTH (Whakahau) OF THAMES THAMES Kauaeranga Valley OPOUTERE Pukorokoro/Miranda 25a Kopu ONEMANA MARAMARUA 25 Pipiroa To Auckland Kopuarahi Waitakaruru 2 WHANGAMATA Hauraki Plains Maratoto Valley Wentworth 2 NGATEA Mangatarata Valley Whenuakura Island 25 27 Kerepehi Hikutaia Kopuatai HAURAKI 26 Waimama Bay Wet Lands RAIL TRAIL Whiritoa To Rotorua/ Netherton Taupo PAEROA Waikino Mackaytown WAIHI 2 OROKAWA -

Shaw Cup & Fleming Shield Tournament

THAMES VALLEY RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION SHAW CUP & FLEMING SHIELD 2021 Aim: To provide an opportunity for as many Year 8 and below students as possible to experience the enjoyment of rugby and to play in a tournament under specific rules and conditions. Dates: Saturday 31st July – Rhodes Park, Thames. Saturday 7th August – Sports Park, Whitianga. Saturday 21st August – Boyd Park, Te Aroha. Grades: There will be two grades of competition: • Shaw Cup (Year 7 and below students) • Fleming Shield (Year 8 and below students) Only one team may be entered in each grade from the regions listed below of the Thames Valley Rugby Football Union (TVRFU) Inc. The Year Groups specified for each competition must be met by ALL players on the official date of the first day. Shaw Cup - Player eligibility: • Must be a Year 7 or below Student as of the 1st January 2021. • There are NO Secondary School Students eligible to play. • There is NO weight limit. • Must attend a school located within the TVRFU Provincial Boundaries or are registered before the 3rd July 2021 to a club affiliated to the Thames Valley Rugby Football Union. • Any player attending Thames Valley Schools that play Hockey, Soccer, Netball, Rugby league etc. are eligible to play in the Shaw Cup and Fleming Shield Tournament. Fleming Shield - Player eligibility: • Must be a Year 8 or below Student as of the 1st January 2021. • There are NO Secondary School Students eligible to play. • There is NO weight limit. • Must attend a school located within the TVRFU Provincial Boundaries or are registered before the 3rd July 2021 to a club affiliated to the Thames Valley Rugby Football Union. -

Ferry Landing, Cooks, Hahei and Hot Water Beaches Reserve Management Plan

Ferry Landing, Cooks, Hahei and Hot Water Beaches Reserve Management Plan Document 2 Individual Reserve Plans Reserves Act 1977 Awaiting Council Approval June 2007 Mercury Bay South Reserve Management Plan Document 2: Individual Reserve Plans Part 3: Reserve Plans Maps: Mercury South Reserve Area Map: Map 1 Ferry Landing Index Map Map 2 Cooks Beach Index Map Map 3 Hahei Index Map Map 4 Hot Water Beach Index Map Map 5 Whenuakite - Coroglen Index Map Map 6 Section 9: Individual Reserve Action Plans – specific reserve policies and actions page 3 Managing reserves – table identifying how reserves are categorised and managed. page 4 Index to Reserves listed in Section 9 page 6 Detail on layout of individual reserve plan page 7 Cooks Beach Reserves page 8 Ferry Landing Reserves page 25 Hahei Reserves page 31 Hot Water Beach Reserves page 46 Section 10 Index of other reserves covered under Document 1: Generic Objectives and Policies page 54 Mercury Bay South Reserve Management Plan Document 2: Individual Reserve Plans MAP 1 – Mercury South Reserve Area PortPort JacksonJackson ))) ))) PortPort CharlesCharles LittleLittle BayBayBay !!! COLVILLECOLVILLE !!! TuateawaTuateawa WaiteteWaitete BayBay ))) KENNEDYKENNEDY BAYBAY OtamaOtama PapaPapa ArohaAroha ))) WHANGAPOUA ))) ))) OpitoOpito MATARANGI ))) OpitoOpito KuaotunuKuaotunu ))) KuaotunuKuaotunu OamaruOamaru BayBay RingsRings BeachBeach COROMANDELCOROMANDEL !!! TeTe RerengaRerenga TeTe KoumaKouma ))) WharekahoWharekaho ))) WHITIANGA FerryFerry LandingLanding ))) COOKSCOOKS BEACHBEACH !!! ))) ManaiaManaia -

Coromandel Peninsula Itineraries

Coromandel Peninsula Itineraries 3 + Day Itinerary Ideas for the Coromandel Peninsula (Including some of our favourite things) Whitianga Campgrounds: • Harbourside Holiday Park 135 Albert Street Whitianga 07 866 5746 • Whitianga Holiday Park 6 Bongard Road Whitianga 07 866 5834 • Mercury Bay Motor Camp 121 Albert Street Whitianga 07 866 5579 Activities: • Surf cast off the beach or fish off the wharf. • Collect Pipis, (a shellfish common in NZ waters). Ask us where to find them & we’ll give you some recipe ideas. • Eat fresh fish & chips on the beach for dinner • Take the passenger ferry from Whitianga Wharf over the river to Front Beach where you’ll find good shell collecting & a rope swing at the west end for the kids to play on, as well as rocks to climb & explore • Visit Whitianga museum, then take the ferry & walk to Whitianga Rock & Back Bay to appreciate what you’ve just learnt • If you’re aged over 10 years, try your hand at bone carving • Take the kids and: hire a quad bicycle for a family tour around town, play mini golf, head to the bike park & walk up to the newly discovered kauri grove, see the animals at Whiti Farm Park or Millcreek Bird Park. Climb the ropes at High Zone, play paintball or ride a quad bike at Combat Zone. • Adults can enjoy The Lost Spring on Cook Drive • Discover Whitianga for more activities and ideas. See our local events & festivals South of Whitianga Campgrounds: • Hahei Holiday Resort Harsant Avenue Hahei 07 866 3889 • Cooks Beach Holiday Resort crn Purangi & Rees Ave Cooks Beach 07 866 5469 • Flaxmill Bay Hideaway 1031 Purangi Road Cooks Beach 07 866 2386 • Seabreeze Holiday Park 1043 Taiura Whitianga Road Whenuakite 07 866 3050 • Mill Creek Bird Park 365 Mill Creek Road Kaimarama 07 866 0166 • Hot Water Beach Top 10 Holiday Park 790 Hot Water Beach Road Hot Water Beach 07 8663116 • Riverglen Holiday Camp Tapu Coroglen Road Coroglen 07 866 3130 Activities: • At low tide, dig yourself a hot pool at Hot Water Beach. -

SETTLEMENTS Usually Resident Population

MAIN SETTLEMENTS Usually Resident Population The majority of the usually resident population of the Coromandel Peninsula The largest settlements in the Thames-Coromandel District are Cooks Beach, lives in one of the main settlements of the District. In 2006, this figure was Coromandel, Matarangi, Pauanui, Tairua, Thames, Whangamata and almost 74% – which is similar to previous census years. Whitianga. Each of the main settlements has different population and growth characteristics. It is important to take these characteristics into account when Between the 1996 and 2006 census nights, the overall usually resident planning and delivering Council services and facilities – both now and in the population of the District increased, despite the fact that there was a decrease future. in the usually resident population of some of the main settlements. The graph below illustrates the changes in the usually resident populations of the main In order to protect the privacy of census participants, Statistics New Zealand settlements over the past ten years. The population figure shown on the does not release data when the size of the subject population for a particular graph is from the 2006 Census. category is too small. Hence, data is unavailable in some categories for the smaller settlements in the District (Cooks Beach, Matarangi, Pauanui and Tairua). Usually Resident Population of the Main Settlements 7,542 8,000 1996 This section of the document compares and contrasts the characteristics of 2001 2006 the main settlements in the Thames-Coromandel District. Information on each 6,000 individual main settlement can be found in Appendix C. Usually 3,567 3,768 Re s ide nt 4,000 Population 1,617 2,000 1,296 723 318 249 0 h ui ta ndel an a eac u ames a Tairua h ianga B atarangi P T ks M Whit Coroma Coo Whangam In 2006 Thames had a usually resident population of 7,542 people followed by Whitianga with 3,768 people and Whangamata with 3,567 people. -

HOMEGROWN in the COROMANDEL

HOMEGROWN in THE COROMANDEL OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE REFER TO CENTRE FOLDOUT www.thecoromandel.com Hauraki Rail Trail, Karangahake Gorge CAPE COLVILLE Fletcher Bay PORT JACKSON COASTAL WALKWAY Stony Bay MOEHAU RANGE Sandy Bay Fantail Bay PORT CHARLES HAURAKI GULF Waikawau Bay Otautu Bay COLVILLE Amodeo Bay Kennedy Bay Papa Aroha NEW CHUM BEACH KUAOTUNU Otama Shelly Beach MATARANGI BAY Beach WHANGAPOUA BEACH Long Bay Opito Bay COROMANDEL Coromandel Harbour To Auckland TOWN Waitaia Bay PASSENGER FERRY Te Kouma Te Kouma Harbour WHITIANGA Mercury Bay Manaia Harbour Manaia 309 Cooks Marine Reserve Kauris Beach Ferry CATHEDRAL COVE Landing HAHEI C OROMANDEL RANGE Waikawau HOT WATER COROGLEN BEACH 25 WHENUAKITE Orere 25 Point TAPU Sailors Grave Rangihau Square Valley Te Karo Bay WAIOMU Kauri TE PURU TAIRUA To Auckland Pinnacles Broken PAUANUI 70km KAIAUA Hut Hills Hikuai DOC PINNACLES Puketui Tararu Info WALK Shorebird Coast Centre Slipper Island 1 FIRTH (Whakahau) OF THAMES THAMES Kauaeranga Valley OPOUTERE Pukorokoro/Miranda 25a Kopu ONEMANA MARAMARUA Pipiroa 25 To Auckland Waitakaruru Kopuarahi 2 WHANGAMATA Hauraki Plains Maratoto Valley Wentworth 2 NGATEA Mangatarata Valley Whenuakura Island 25 27 Kerepehi Hikutaia Kopuatai HAURAKI 26 Waimama Bay Wet Lands RAIL TRAIL Whiritoa To Rotorua/ Netherton Taupo PAEROA Waikino Mackaytown WAIHI 2 OROKAWA BAY Tirohia KARANGAHAKE GORGE Waitawheta WAIHI BEACH Athenree KEY Kaimai Marine Reserve Walks Golf Course Forest Park Bowentown Gold Heritage Fishing Information Centres Surfing Cycleway Airports TE AROHA To Tauranga 70km Kauri Heritage Camping life asitshouldbe. slow downandreconnectwith abreak, it’s time to relax.Take selling homegrown foodandart, and meetingcreativelocals you. Aftersomeretailtherapy perfect, becauseit’s allabout The Coromandel is a prescription for your own own your is aprescriptionfor wellbeing. -

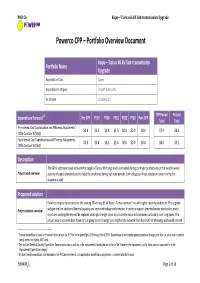

Powerco CPP – Portfolio Overview Document

POD G6 Kopu—Tairua 66 kV Sub-transmission Upgrade Powerco CPP – Portfolio Overview Document Kopu—Tairua 66 kV Sub-transmission Portfolio Name Upgrade Expenditure Class Capex Expenditure Category Growth & Security As at Date 12 June 2017 CPP Period Project Expenditure Forecast 1,2 Pre CPP FY19 FY20 FY21 FY22 FY23 Post CPP Total Total Pre-Internal Cost Capitalisation and Efficiency Adjustments 3 $0.6 $3.5 $2.9 $1.5 $0.0 $0.0 $0.0 $7.9 $8.5 (2016 Constant NZ$(M)) Post-Internal Cost Capitalisation and Efficiency Adjustments $0.6 $3.8 $3.2 $1.6 $0.0 $0.0 $0.0 $8.6 $9.2 (2016 Constant NZ$(M)) Description The 66 kV subtransmission network that supplies Tairua, Whitianga and Coromandel during contingency situations cannot meet Powerco Project need overview security of supply standards due to capacity constraints during high load periods. Low voltages at these substations occur during this situation as well. Proposed solution Powerco propose to reconductor the existing 33 km long 66 kV Kopu – Tairua overhead line with higher capacity conductors. The upgrade Project solution overview will give the line additional thermal capacity and improved voltage performance. In order to support the new heavier conductors, many structures carrying the line will be replaced with high-strength poles to provide the required clearances particularly over long spans. The project would accommodate Powerco’s ongoing future strategy to strengthen the network from Kopu GXP to Whitianga and would remove 1 Forecast expenditure is based on Powerco’s financial year (i.e. FY19 is for the period April 2018 through March 2019). -

Whenuakite Kiwi Care Operational Programme

10 July 2020 Whenuakite Kiwi Care Operational Programme Doc # 16808277 Page 1 SECTION ONE: Project Information 1. Project summary Project title Whenuakite Kiwi Care Operational Programme Name of applicant/community group Whenuakiwi Trust t/a Whenuakite Kiwi Care Group Contact person(s) 1 - S7(2)(a) LGOIM... 1 - S7(2)(a) LGOIMA 1987 1 1 -- S7(2)(a) LGOIM... LGOIMA 1987 Legal entity status Charitable Trust CC10895 Short project description Whenuakiwi Trust has been operating since 2001 on 2570ha of private land and 984ha of Public Conservation Land (PCL). Our mission statement from 2000 states: “To promote the welfare of Kiwi and their habitat in the Whenuakite and surrounding area.” We achieve this with a trap network consisting of 553 traps spread over about 110km of trapline. We target all introduced species with a focus on mustelids and a bi- kill of rats, hedgehogs and feral cats. Our initial aim was to protect kiwi. But our approach and dedication to conservation has led to a thriving habitat allowing other indigenous species to flourish. In partnership with Iwi, Department of Conservation (DOC) and Waikato Regional Council (WRC) we utilise aerial 1080. We chose early on not to handle our kiwi. We employ a contractor to co-ordinate volunteers trapping 141 traps; he also services 212 (141 private land, 68 PCL) traps for WKCG . Many of our private landowners fund their own traps (200) and maintain their own lines. Our long- term goal is to forever ensure predator numbers are kept as low as possible by utilising best practice methods. Our results show that our methods are working as we have attained a growth in kiwi numbers consistently for every survey that has been done. -

Kauaeranga Valley and Broken Hills Brochure And

COROMANDEL Contents Kauaeranga valley recreation 2 Further information Kauaeranga valley Kauaeranga valley area map 6 Track information is correct at date of Introduction 7 printing but facilities and services can and Broken Hills Location map 7 change. Check with the Kauaeranga Enjoying the outdoors safely 9 Visitor Centre. Kauaeranga short walks 10 Department of Conservation Kauaeranga walking tracks 11 Kauaeranga Visitor Centre Kauaeranga tramping tracks 15 PO Box 343, Thames 3540 Other activities 18 PHONE: (+64) 7 867 9080 Huts 19 EMAIL: [email protected] Camping 21 Please remember 23 www.doc.govt.nz Kauri dams 24 Broken Hills recreation 25 Introduction 25 Please remember 27 Broken Hills area map 29 Track guide 31 Wildlife 34 Further information Back page Cover image: Cookson Kauri. All photos: DOC unless stated otherwise Published by: Department of Conservation Kauaeranga Visitor Centre PO Box 343 Thames 3540 October 2019 Editing and design: DOC Creative Services Conservation House, Wellington This publication is produced using paper sourced from well-managed, renewable and legally logged forests. 9 421005 171273 > R162522 Kauaeranga Visitor Centre. 1 2 3 to Tapu Coroglen Road to Rangihau roadend KauaerangaKauaeranga valley Valley walking walking andand trampingtramping ttracksracks T A P Waiomu Kauri Grove U Waiomu S U M M W IT AIO TO MU T C RACK R O S B Dam IE Moss Creek S H M U O T 720m S Main Kauaeranga C O R O M A N D E L F O R E S T P A R K S Dam ACK C TR R U E R E U Dancing Camp P K E T Dam T Te Puru R A Crosbies Hut -

Conservation Campsites North Island 2019-20 Coromandel

Cape Reinga 1 Kaitaia 10 Kerikeri 1 Kaikohe 12 1 WHANGĀREI 14 Dargaville Mangawhai Heads COROMANDEL 12 1 Note: All Coromandel Great Barrier Island campsites other than (Aotea Island) Kauaeranga Valley campsites Warkworth 3 are pack in, pack out (no 2 rubbish or recycling facilities). 16 4 1 1 See page 3. Orewa 5 Helensville 25 Whanganui A Hei Marine Reserve AUCKLAND Whitianga Coromandel Forest Park 3343536937383 1 678 16 Thames Pukekohe Kauaeranga Visitor Centre 17 Waiuku 25 Whangamatā Tuakau 2 26 25 2 Paeroa Waihi 27 1 Te Aroha Huntly Katikati Ngāruawāhia Morrinsville 2 26 TAURANGA 27 Raglan HAMILTON 23 Te Puke Matamata 29 35 2 Cambridge 1 0 25 50 km WHAKATANE 35 Te Awamutu EdgecumbeOhope Opotiki 33 31 Putaruru 5 3 Warning: Coromandel 30 Kauaeranga Visitor Centre Kawerau weatherROTORUA can change P KauaerangaOtorohanga Valley Rd 1 2 Thames TOKOROAvery quickly, with rivers and streams rapidly reaching5 P (07) 867 9080 30 Te Kuiti flood levels in heavy or P [email protected] prolonged rainfall. Coastal areas can also be affected. 38 30 Murupara 2 3 1 5 35 4 Kauri dieback 32Due to demand during disease is Christmas/New Year, we TAUPO killing trees in recommend you book Coromandel. fromLake early to mid-October GISBORNE Help prevent Taupo Taumarunui for northern Coromandel5 the spread – 41 1 3 41 campsites. see page 4. 38 Waitara Turangi Frasertown Lepperton 4 2 NEW PLYMOUTH 47 Oakura 14 46 Wairoa 3 45 Inglewood 2 43 5 Stratford 1 Opunake Eltham Raetihi Ohakune 3 49 Waiouru Normanby 45 NAPIER Hawera 1 Taihape HASTINGS 4 3 50 2 WANGANUI 1 Otane Waipawa 3 Waipukurau Marton 2 54 Bulls Feilding 3 Dannevirke Ashhurst 1 3 Woodville 56 PALMERSTON NORTH Foxton Beach Foxton Pahiatua 57 2 Shannon LEVIN Eketahuna Otaki 1 2 MASTERTON Carterton 2 Greytown 1 Featherston LOWER HUTT 53 Martinborough WELLINGTON 0 25 50 100 150 km COROMANDEL 1 Fantail Bay 29 Camp beneath pōhutukawa trees in peaceful surroundings, with swimming, fishing, diving nearby.