Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish River Scenic Byway

Fish River Scenic Byway State Route 11 Aroostook County Corridor Management Plan St. John Valley Region of Northern Maine Prepared by: Prepared by: December 2006 Northern Maine Development Commission 11 West Presque Isle Road, PO Box 779 Caribou, Maine 04736 Phone: (207) 4988736 Toll Free in Maine: (800) 4278736 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ...............................................................................................................................................................3 Why This Byway?...................................................................................................................................................5 Importance of the Byway ...................................................................................................................................5 What’s it Like?...............................................................................................................................................6 Historic and Cultural Resources .....................................................................................................................9 Recreational Resources ............................................................................................................................... 10 A Vision for the Fish River Scenic Byway Corridor................................................................................................ 15 Goals, Objectives and Strategies......................................................................................................................... -

Outdoors in Maine: Red River Country

Outdoors in Maine: Red River country By V. Paul Reynolds Published: Jul 05, 2009 12:00 am Most serious fishermen I have known tend to be secretive about their best fishing holes. I'm that way. Over the years, I've avoided writing about my most coveted trout "honeyholes" for fear of starting a stampede and spoiling a good thing. For some reason, though, age has a way of mellowing your protectionist instincts about special fishing places. At least, that's how it is for me. So pull up a chair and pay attention. You need to know about Red River Country. Red River Country comprises a cluster of trout ponds in northernmost Maine on a lovely tract of wildlands in the Deboullie Lake area ( T15R9) owned by you and me and managed by the Maine Bureau of Public Lands . (Check your DeLorme on page 63). A Millinocket educator, Floyd Bolstridge, first introduced this country to me back in the 1970s. Diane and I have been making our June trout-fishing pilgrimage to this area just about every year since. Back then, Floyd told about walking 20 miles with his father in the late 1940s to access these ponds. He and his Dad slept in a hastily fashioned tar paper lean-to, dined on slab-sided brookies, and stayed for weeks. Floyd said that the fishing wasn't as good 30 years later. Today, almost 40 years since Floyd recounted for me his youthful angling days in Red River Country, the fishing isn't quite as good as it was. -

Take It Outside Adult Series “Outings and Classes to Help ADULTS “Fall” Into Shape” August 20 – November 19, 2020

Take It Outside Adult Series “Outings and Classes to help ADULTS “fall” into shape” August 20 – November 19, 2020 Caribou Wellness & Recreation Center 55 Bennett Drive Caribou, Maine 04736 207-493-4224 http://www.caribourec.org/ [email protected] Take it Outside Fall Series Schedule Outings & Classes to Help Adults “Fall” Into Shape! August August 20-21 – Monson, Greenville & Mooseshead Lake Tour aboard Steamship Katahdin, Greenville, Me $260 Single/$180 Double Occupancy. Depart 8am. Back by popular demand, but instead of rushing this year, we’re spending the night at the lovely Chalet Moosehead Lakefront Motel, which will afford us the opportunity to relax and see more! We had such an overwhelming response to this opportunity we had to reoffer. Space quickly filled up on this outing, so don’t wait. Preregister today to reserve one of the 7 coveted spots available. Trip includes one breakfast and two lunches. Dinner not included but we will eat together as a group. Trip will return Friday evening. Max 7, Min. of 6 paid in full preregistered participants by August 6 August 26-27 – Lubec, Maine and Campobello Island, NB CA - $200 Single/$165 Double Occupancy. This sightseeing trip will take us to Downeast Maine! Depart 7am, travel to Washington County via US Route 1 passing though Calais with a brief side trip into Eastport before ultimately arriving at our destination in Lubec. Wednesday afternoon while in Lubec we will visit Quoddy Head and tour the historic downtown working waterfront of Lubec. Wednesday evening, we will stay at the Eastland Motel. Thursday morning, we will visit Franklin Roosevelt International Park Campobello Island. -

North Maine Woods2013 $3

experience the tradition North Maine Woods2013 $3 On behalf welcomeof the many families, private corporations, conservation organizations and managers of state owned land, we welcome you to this special region of Maine. We’re proud of the history of this remote region and our ability to keep this area open for public enjoyment. In addition to providing remote recreational opportunities, this region is also the “wood basket” that supports our natural resource based economy of Maine. This booklet is designed to help you have a safe and enjoyable trip to the area, plus provide you with important information about forest resource management and recreational use. P10 Katahdin Ironworks Jo-Mary Forest Information P14 New plan for the Allagash Wilderness Waterway P18 Moose: Icon of P35 Northern Region P39 Sharing the roads the North Woods Fisheries Update with logging trucks 2013 Visitor Fees NMW staff by photo RESIDENT NON-RESIDENT Under 15 .............................................................. Free Day Use & Camping Age 70 and Over ............................................... Free Day Use Per Person Per Day ...................................................$7 ................ $12 Camping Per Night ....................................................$10 ............. $12 Annual Day Use Registration ...............................$75 ............. N/A Annual Unlimited Camping ..................................$175 .......... N/A Checkpoint Hours of Operation Camping Only Annual Pass ...................................$100 .......... $100 Visitors traveling by vehicle will pass through one of the fol- lowing checkpoints. Please refer to the map in the center of Special Reduced Seasonal Rates this publication for locations. Summer season is from May 1 to September 30. Fall season is from August 20 to November 30. Either summer or fall passes NMW Checkpoints are valid between August 20 and September 30. Allagash 5am-9pm daily Caribou 6am-9pm daily Seasonal Day Use Pass ............................................$50 ............ -

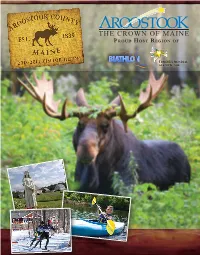

Aroostook County Visitor Guide © Visitaroostook.Com 1 the Trail Less Traveled

PROUD HOST REGION OF Aroostook County Visitor Guide © visitaroostook.com 1 The Trail Less Traveled E NJOY A VISIT TO A ROOSTOOK C OUNTY , M AINE Amid a natural wonderland, visitors to the largest county east of the Mississippi River revel in a place populated by friendly folk and free roaming wildlife, in a land watered by thousands of miles of clear-running streams and hundreds of lakes. When coupled with the Great North Woods covering a vast region larger than many states, Aroostook County is your destination for uncrowded recreational pursuits, wildlife viewing, hunting and fishing – or just a solitary walk along the trail less traveled. Aroostook County’s pristine beauty and cultural heritage make VISION: it the ideal destination for an uncomplicated experience. To develop and implement a tourism MISSION: marketing program for Aroostook County. This publication produced by Aroostook County Tourism 888-216-2463 and Paid for in part by a grant from the Northern Maine Development Commission (800) 427-8736. Maine Office of Tourism. For more information, visit these websites: For additional information on Maine, visitaroostook.com & nmdc.org call 1-888-MAINE45 or go to visitmaine.com. 2 Aroostook County Visitor Guide © visitaroostook.com AROOSTOOK COUNTY NORTH MAINE WOODS AROOSTOOK STATE PARK How to use this map & guide North Maine Woods ....................Green St. John Valley ............................Yellow NORTH Central Aroostook ..........................Blue GATE TO Southern Aroostook........................Red BAXTER SHIN D ISTAN C ES POND W IT H IN A ROOSTOOK T O A ROOSTOOK Fort Kent to Caribou .......... 45 miles New York, NY ............601 miles Madawaska to Houlton .... -

Visitor's Guide

MAINE KatahdinMaine.com VISITOR’S GUIDE Welcome Stop at the Chamber office at 1029 Central Street, Millinocket for trails, maps, guidance and more! Download the Discover Katahdin App so you can access information while on the move. Maine is home to many mountains and several state parks but there is only one mile-high Katahdin, the northern terminus INSIDE of the Appalachian Trail, located in the glorious Baxter State ATV Trails Park. Located right “next door” is the Katahdin Woods and & Rules ........... 63-65 Waters National Monument. These incredible places are right Multi-Use Trail here in the Katahdin Region. Make us your next destination— Map (K.R.M.U.T.) .... ......................66-67 for adventures in our beautiful outdoors, and experiences like none other. Let us help you Discover Your Maine Thing! Canoeing & Kayaking .........56-61 Located in the east central portion of the state, known as The Map ............... 50-51 Maine Highlands, the Katahdin region boasts scenic vistas Children’s Activities ...18 and abundant wildlife throughout northern Penobscot Coun- ty’s hilly lake country, the rolling farm country of western Pe- Cross-Country Skiing nobscot, and southern Aroostook’s vast softwood flats. The & Snowshoeing....68-71 area is home to incredible wildlife; including our local celeb- Maps ............. 72-79 rity the moose, as well as osprey, bald eagles, blue herons, Directory beaver, black bear, white-tailed deer, fox and more. of Services ...... 82-97 Festivals ...............98 Visit in spring, summer and fall to enjoy miles of hiking trails—from casual walks to challenging hikes, kayaking and Getting Here .......... 5 canoeing on pristine lakes, white water rafting with up to Katahdin Area Class V rapids, world class fishing for trout, landlocked salmon Hikes .............. -

Penobscot River Corridor & Seboomook Public Land

www.parksandlands.com Property History When to Visit Bureau of Parks and Lands and Parks of Bureau he rivers, streams, and lakes in the Seboomook/Pe- The best paddling is between May and September, with the fish- nobscot region were highways for native people, who ing usually best in either of those “shoulder season” months. Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry and Conservation Agriculture, Thave been present here for nearly 12,000 years. Canoe Recreational dam releases tend to occur on Saturdays during routes in the region date back at least 1,000 years, linking the July, August and September: call GLHA at 1- 888-323-4341 Maine Department of Department Maine Kennebec, Penobscot, and Allagash rivers, are still enjoyed for more on Canada Falls and Seboomook dam releases. For today by recreational paddlers traveling the historic 740-mile more on timing of McKay Station (Ripogenus Dam) releases, Northern Forest Canoe Trail. call Brookfield Power at 1-888-323-4341. Some of these paddling routes were taken by writer and naturalist Mosquitoes and black flies are thickest in late May through Overview Upper West Branch and Lobster Lake Henry David Thoreau on three extended trips between 1846 and July. Various types of hunting take place in fall, with bear bait 1857. Thoreau’s The Maine Woods describes his journey into a season generally during September, moose hunting from late he upper reaches of the Penobscot River run through a The wildest portion of the corridor, the Upper West Branch wild landscape that attracted both adventurers and lumbermen. September through mid-October, and firearms season for deer mountainous, forested landscape defined by the power- offers scenic canoeing, camping and fishing (with gentle waters in November. -

Discover New Places to Hike, Bike

Allagash Falls by Garrett Conover Explore MAINE 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE: Discover New Places to Hike, Bike, Swim, & More Favorite Protected Places Where in Maine do you want to go this summer? This year’s edition of Explore Maine offers spectacular places personally picked by NRCM staff, board, and members who know them well. Working together, over the last Books & Blogs 60 years, we helped ensure these places would be always be protected, for generations to come. We hope by NRCM Members you’ll make time to enjoy any and all of these recommendations. For even more ideas, visit our online Explore Maine map at www.nrcm.org. Cool Apps It is also our pleasure to introduce you to books and blogs by NRCM members. Adventure books, Explore Great Maine Beer biographies, children’s books, poetry—this year’s collection represents a wonderful diversity that you’re sure to enjoy. Hear first-hand from someone who has taken advantage of the discount many Maine sporting camps Maine Master provide to NRCM members. Check out our new map of breweries who are members of our Maine Brewshed Naturalist Program Alliance, where you can raise a glass in support of the clean water that is so important for great beer. And Finding Paradise we’ve reviewed some cool apps that can help you get out and explore Maine. Enjoy, and thank you for all you do to help keep Maine special. Lots More! —Allison Wells, Editor, Senior Director of Public Affairs and Communications Show your love for Explore Maine with NRCM a clean, beautiful Paddling, hiking, wildlife watching, cross-country skiing—we enjoy spending time in Maine’s great outdoors, and you’re invited to join us! environment Find out what’s coming up at www.nrcm.org. -

Overstory: Ecosystems Are Intertwined

Over STORY Timber Research Environmental Education Volume 1 Number 2 Fall 2019 Newsletter of the Maine Tree Foundation President’s Message Connections! By Marcia McKeague, President By Henry Whittemore, Executive Director In reflecting over a busy year at the Maine TREE As I prepare to make my annual donation to Foundation, I find myself considering what makes the Maine TREE Foundation, I think about this organization special. For me, the answer is the whether our programs are still relevant to our connections this organization creates between Maine’s times. Climate change is far and away the forests and the communities and economy that derive so most serious environmental issue of our times much of their own identities from the forest. If you read and it is clear that the next generation wants our mission statement: “The Maine TREE Foundation meaningful action from the generations who are educates and advocates for the sustainable use of “in charge”. Trees and forests are and can be a key the forest and the ecological, economic and social health part of the solution. With our programs aimed at of Maine’s forest community,” this seems obvious, but educating teachers, students, landowners, loggers, the connections that come to mind since taking on the foresters and recreational users and our advocacy leadership of this organization extend well beyond the for sustainable use of forests, we are part of the mission statement. solution. Maine TREE is closely connected to nearly every aspect I also think with great appreciation of the people of Maine’s forested landscape. Through our programs who have come before me and who stand beside we link Mainers to a broad array of topics such as forest me in leading and supporting this endeavor ecology, forest management, silviculture, the forest particularly with this being the 30th year of the products industry, sustainable timber harvesting, safe organization’s existence. -

Understanding Public Access to Private Working Forests in Maine

Understanding public access to private working forests in Maine “Maine has a land-use tradition that is unique in the nation. In Maine, landowners have traditionally allowed members of the public to use their property for a wide variety of recreational activities free of charge.” – James M. Acheson, Professor of Anthropology, University of Maine, Maine Policy Review Page 1 Table of Contents About 4 million acres now conserved statewide ................................3 Let’s work together to preserve access to private land ........................4 Recreational access is a byproduct of working forests .......................5 How certifcation benefts sustainable forestry .................................7 Despite changing landowners, working forest thrives ......................8 Managed forestlands provide many diverse values ............................9 FIN: Solving problems for rivers, fsh, road networks .....................11 Landowners’ concerns are IFW program’s top priority ...................12 North Maine Woods celebrates 48th anniversary ............................13 Where Maine’s wood goes ...................................................Back cover Tis report was produced by the Maine Forest Products Council (MFPC), a not-for- proft, membership-supported trade association formed in 1961. MFPC represents companies from all segments of the forest industry, including logging contractors, sawmills, paper mills, biomass energy facilities, wood manufacturers and the owners of about eight million acres of commercial forestland in Maine. Our thanks to Jake Metzler, Forest Society of Maine, for the map of Maine Conservation Lands on Page 1. Cover photos courtesy of the Maine Snowmobile Association; North Maine Woods; Lonnie Jandreau, Prentiss & Carlisle, and Maine Professional Guides Association. Page 2 Page 3 Let’s work together to preserve access to private land Hi, neighbor! Maine has a lot of great traditions, but Patrick Strauch there’s a very special one – unique in our nation – that binds us all together into one big community. -

2017 Observations of Angler Use in Northern Maine Lakes, 1996-2016 Jeremiah Wood Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, [email protected]

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Resource Management Documents Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Spring 4-21-2017 2017 Observations of Angler Use in Northern Maine Lakes, 1996-2016 Jeremiah Wood Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/brm_docs Recommended Citation Wood, Jeremiah, "2017 Observations of Angler Use in Northern Maine Lakes, 1996-2016" (2017). Resource Management Documents. 15. http://digitalmaine.com/brm_docs/15 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Resource Management Documents by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fishery Progress Report Series No. 17-2 Observations of Angler Use in Northern Maine Lakes, 1996-2016 By: Jeremiah R. Wood Fish River Lakes Region April 2017 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife Fisheries and Hatcheries Division Fisheries and Hatcheries Division Job F-014 Progress Report No. 17-2 Observations of Angler Use in Northern Maine Lakes, 1996-2016 ABSTRACT Understanding angler use and associated fishing pressure is critical to the proper development of fisheries management strategies. We computed estimates of open-water angler use on major lakes and ponds in the Fish, Allagash and upper Aroostook watersheds using flight count data from the mid-1990s and 2010s. Results showed a striking decline in angler use on most waters over the study period, which mirrors demographic trends and is consistent with anecdotal observations. This lower level of angler use highlights the need to reconsider the effectiveness and necessity of current fishing regulations, and the potential to explore options that might better manage fisheries and encourage more angler use in northern Maine. -

2017 AWW Annual Report

AWW Video Photo 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Bureau of Parks and Lands AWW Video Photo AWW Annual Report 2017 Report Contents Mission and Goals………………………………. 2 Historic Preservation……………………… 7 AWW Advisory Council Report………………... 3 Staff Training………………………………. 8 AWW Budget…………………………………….. 4 Forest Operations Notifications………….. 8 FY17 Revenues & Special Funds……………. 4 2017 Project Accomplishments………….. 9 FY17 Expenditure Report………………………. 5 Dam Reports………………………………. 10 Recreation & Visitor Use……………………….. 6 Volunteers…………………………………. 11 Oversize Group Permits………………………… 6 Incidents……………………………………. 11 Education & Interpretation …………………….. 7 Superintendent’s Report…………………. 12 Report Required The Allagash Wilderness Waterway (AWW) is administered by the Bureau of Parks and Lands (BPL) within the Department of Agri- culture, Conservation and Forestry (DACF). A seven-member Advisory Council works with the Waterway manager in developing and maintaining a strategic plan for the Waterway and advancing its mission and goals. The Council is required to report annually to the Director of BPL on the state of the Waterway. Similarly, the Commissioner of the department is required to report annually by March 1st to the Legislature’s joint standing committee on conservation matters regarding the state of the Waterway, including its mission and goals, administration, education and interpretive programs, historic preservation efforts, visitor use and evaluation, ecological conditions and any natural character enhancements, general finances, income, expenditures and balance of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway Permanent Endowment Fund, the department's annual budget request for the Waterway operation in the coming fiscal year and current challenges and prospects for the Waterway (12 MRSA §1890 A-C). This report is submitted to meet both reporting requirements.