Dynamic Spread of Happiness in a Large Social Network: Longitudinal Analysis Over 20 Years in the Framingham Heart Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 18: Heart Disease and Diabetes

CHAPTER 18 HEART DISEASE AND DIABETES Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, MD, Deborah Wingard, PhD, Nathan Wong, PhD, and Ron Goldberg, MD Dr. Elizabeth Barrett-Connor is Distinguished Professor, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health at the University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. Dr. Deborah Wingard is Professor, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health at the University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. Dr. Nathan Wong is Professor and Director of the Heart Disease Prevention Program, Division of Cardiology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA. Dr. Ron Goldberg is Professor of Medicine and Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Diabetes Research Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL. SUMMARY Heart disease remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in type 2 diabetes and is estimated to account for 10%–11% of all vascular deaths. Surveys of the U.S. population have demonstrated an age-standardized differential for heart disease in adults with mostly type 2 diabetes that varies from 1.9 to 2.5. The age-standardized prevalence is about 50% higher in men than women overall and for most categories of heart disease, except congestive heart failure. Although rates of diabetes are higher in nonwhites than in non-Hispanic whites, it should be noted that non-Hispanic whites with diabetes generally report heart disease rates about 50% higher than Hispanic subjects with diabetes, with an intermediate prevalence in non-Hispanic blacks. Despite an approximate doubling in type 2 diabetes prevalence from the 1980s to the 2010s, the prevalence of heart disease in diabetes has remained stable. -

Langley 1 William H. Knight a Village That Is Noted for Its Woolen Twist and Twill, `Tis the Pride of Massachusetts

Langley 1 William H. Knight A village that is noted For its woolen twist and twill, `Tis the pride of Massachusetts And they call it Saxonville. Excerpt from “Saxonville” by J.P., Date Unknown As a lifelong resident of Massachusetts, regions whose affiliations are not readily apparent always intrigue me. I had heard of Saxonville over the years and wondered about it. Was it a town unto itself or part of another community? Where did the name come from? Why was it significant enough to warrant its own historical preservation commission? Saxonville is, in fact, the oldest section of the town of Framingham. Its establishment as a village with its own name was the result of the talent, vision, and perseverance of immigrant William H. Knight whose work turned what was originally known as Stone’s End into Saxonville. Industry along the Sudbury River followed the needs of this region just 20 miles outside of Boston. Settler John Stone was the first to harness the power of the river by erecting a gristmill at the Great Falls of the Sudbury River in 1650, which endured until 1795 when it was converted into a sawmill. In 1811, it was converted into a cotton mill under the auspices of the Framingham Manufacturing Company on the heels of nearby Westborough native Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin. However, “The New England textile industry soon realized that cotton was not king.” (Herring, 2000, p. X) The chilly climate of the region required a warmer material for clothing and bedding in the form of wool. -

Framingham Contribution to Cardiovascular Disease

[Downloaded free from http://www.heartviews.org on Wednesday, October 12, 2016, IP: 62.193.78.199] History of Medicine Framingham Contribution to Cardiovascular Disease Rachel Hajar, M.D. Department of Cardiology, Heart Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar round 17.5 million people die each year from and is now on its third generation of participants. Much cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), an estimated of our appreciation of the pathophysiology of heart 31% of all deaths worldwide. This statistic is disease came from the results of studies from the FHS. A [1] expected to grow to more than 23.6 million by 2030. It established the traditional risk factors, such as high Of these deaths (17.5 million), estimated 7.4 million blood pressure, diabetes, and cigarette smoking for are due to coronary heart disease and 6.7 million are coronary heart disease. Framingham also spearheaded due to stroke.[1] Epidemiologic studies have played an the study of chronic noninfectious diseases in the USA important role in elucidating the factors that predispose and introduced preventive medicine. to CVD and highlighting opportunities for prevention. Most CVDs can be prevented by addressing behavioral ORIGINS OF THE FRAMINGHAM HEART risk factors such as tobacco use, unhealthy diet and STUDY obesity, physical inactivity, and harmful use of alcohol. CVDs are a group of disorders of the heart and In 2013, the FHS celebrated 65 years since its creation. blood vessels, and they include coronary heart disease, The investigation has provided substantial insight cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease; and into the epidemiology of CVD and its risk factors. -

Prevalence of Coronary Heart Disease by Age and Sex

Prevalence of coronary heart disease by age and sex National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2009–2012. Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Prevalence of myocardial infarction by age and sex National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2009–2012. Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Annual number of adults per 1000 having diagnosed heart attack or fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) by age and sex Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Surveillance: 2005–2011 and Cardiovascular Health Study. Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Incidence of heart attack or fatal coronary heart disease by age, sex, and race Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Surveillance: 2005–2011. Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Incidence of myocardial infarction by age, sex, and race Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Surveillance: 2005-2011. Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Estimated 10-year coronary heart disease risk in adults 55 years of age according to levels of various risk factors (Framingham Heart Study). Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Prevalence of low coronary heart disease risk, overall and by sex National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 1971–2006. Mozaffarian D et al. Circulation. 2015;131:e29-e322 Copyright © American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. -

Project Retrosight: Understanding the Returns from Cardiovascular And

WORKING P A P E R Project Retrosight Understanding the returns from cardiovascular and stroke research Case Studies ALEXANDRA POLLITT, STEVEN WOODING, STEPHEN HANNEY, MARTIN BUXTON AND JONATHAN GRANT WR-836-RS March 2011 Prepared on behalf of the Project Retrosight Team Approved for public release, distribution unlimited This product is part of the RAND Europe working paper series. RAND working papers are intended to share researchers’ latest findings and to solicit informal peer review. They have been approved for circulation by RAND Europe but have not been formally edited or peer reviewed. Unless otherwise indicated, working papers can be quoted and cited without permission of the author, provided the source is clearly referred to as a working paper. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. Preface This report presents a set of 29 case studies of cardiovascular and stroke research grants funded in three countries between 1989 and 1993. The case studies focused on the individual grants but considered the development of the investigators and ideas involved in the research projects from initiation to the present day. Basic biomedical and clinical cardiovascular and stroke research grants awarded in Australia, Canada and the UK were selected through a stratified random selection approach that aimed to include both high- and low-impact grants. Case studies were constructed around the Payback Framework1, a research evaluation framework that is both a tool for evaluating a range of potential outputs from research and a logic model that provides a mechanism for conceptualising the process through which outputs are created. -

March 1985 No. 85: BUSM News and Notes

Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu BU Publications BUSM News and Notes 1985-03 BUSM News & Notes: March 1985 no. 85 https://hdl.handle.net/2144/22078 Boston University News & Notes Boston University School of Medicine March 1985 Issue #85 BUSM FORMS NEW AFFILIATIONS Joseph J. Vitale, Sc.D., M.D., associate dean WITH CHINA AND ISRAEL for international health and director of the BUSM Nutrition Education Program, recently spent several weeks in northern China to finalize an affiliation between the School of Medicine and several medical centers there. Vitale visited the medical schools and hospitals of participating medical centers in the provinces of Liaoning, Heilongjiang and Jilin. In addition, an affiliation has been developed between the School of Medicine and the Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem, Israel. Vitale, Dean Sandson, Ernest H. Blaustein, Ph.D., associate dean of the College of Liberal Arts, and Leonard S. Gottlieb, M.D., a professor and chairman of the Department of Pathology, participated in the ceremony establishing the affiliation held at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Both affiliations will allow an exchange of students and faculty, and will promote the joint sponsorship of continuing medical education conferences and research activities. The exchange programs are similar to ones already in place between BUSM and medical schools in Egypt, Columbia (South America), Ireland, and Mexico. LOWN TO SPEAK ON NUCLEAR Bernard Lown, M.D., president of MENACE AT ALUMNI MEETING International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and founder and first president of Physicians for Social Responsibility, will be the keynote speaker at the BUSM Alumni Association's annual meeting and banquet to be held May 11 at the 57 Park Plaza Hotel. -

Framingham Heart Study Longitudinal Data Documentation for Teaching Dataset

Framingham Heart Study Longitudinal Data Documentation The Framingham Heart Study is a long term prospective study of the etiology of cardiovascular disease among a population of free living subjects in the community of Framingham, Massachusetts. The Framingham Heart Study was a landmark study in epidemiology in that it was the first prospective study of cardiovascular disease and identified the concept of risk factors and their joint effects. The study began in 1948 and 5,209 subjects were initially enrolled in the study. Participants have been examined biennially since the inception of the study and all subjects are continuously followed through regular surveillance for cardiovascular outcomes. Clinic examination data has included cardiovascular disease risk factors and markers of disease such as blood pressure, blood chemistry, lung function, smoking history, health behaviors, ECG tracings, Echocardiography, and medication use. Through regular surveillance of area hospitals, participant contact, and death certificates, the Framingham Heart Study reviews and adjudicates events for the occurrence of Angina Pectoris, Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, and Cerebrovascular disease. The enclosed dataset is a subset of the data collected as part of the Framingham study and includes laboratory, clinic, questionnaire, and adjudicated event data on 4,434 participants. Participant clinic data was collected during three examination periods, approximately 6 years apart, from roughly 1956 to 1968. Each participant was followed for a total of 24 years for the outcome of the following events: Angina Pectoris, Myocardial Infarction, Atherothrombotic Infarction or Cerebral Hemorrhage (Stroke) or death. (NOTE: Although the enclosed dataset contains Framingham data ‘as collected’ by Framingham investigators, specific methods were employed to ensure an anonymous dataset that protects patient confidentiality; therefore, this dataset is inappropriate for publication purposes. -

Department of Medicine NEWSLETTER

Department of Medicine NEWSLETTER Spring 2019 Message from the Chairman Colleagues, As the colors of spring explode in Boston, I hope you will enjoy this latest edition of the Department of Medicine’s electronic newsletter! We celebrate a number of extraordinary accomplishments in this edition! The renewal of the Framingham Heart Study contract by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute is a remarkable testament to the impact of this iconic study over the past 70 years and the creative and thoughtful leadership of the study’s leader- Vasan Ramachandran, M.D. In addition, the Mass HEAL award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Boston Medical Center under the leadership of Jeffrey Samet, M.D., is a tribute to the long-standing leadership of the faculty and staff in General Internal Medicine in devising new approaches to the prevention and treatment of opiate use disorder. Importantly, the research funded by these two awards will have a critically important and enduring impact on the health of our patients. The recent resident match was also quite successful! We matched a large number of applicants from the top of our rank list and had a more selective result than in any of the previous 12 years! Although the intern class has diverse geographic representation, we continue to be challenged in recruiting interns from backgrounds under-represented in medicine. The successful match is a tribute to the leadership of Drs. Rachel Simmons and Gopal Yadavalli, and the tireless commitment of the faculty, administrative staff in the program office, and, importantly, the many residents who participate in the intern recruitment process! The establishment of EPIC Leads in the department is described in this edition of the newsletter. -

Institutional Master Plan Renewal Boston University

INSTITUTIONAL MASTER PLAN RENEWAL BOSTON UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER MARC H 22, 2010 SUBMITTED TO: BOSTON REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY ONE CITY HALL SQUARE BOSTON, MA 02201 SUBMITTED PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 80D OF THE BOSTON ZONING CODE SUBMITTED BY: BOSTON MEDICAL CENTER CORPORATION ONE BOSTON MEDICAL CENTER PLACE BOSTON, MA 02118 TRUSTEES OF BOSTON UNIVERSITY ONE SILBER WAY, SUITE 904 BOSTON, MA 02115 PREPARED BY: IN ASSOCIATION WITH: RFWalsh collaborative partners TSOI/KOBUS & ASSOCIATES 51 SLEEPER STREET HOWARD/STEIN-HUDSON BOSTON, MA 02210 RUBIN AND RUDMAN LLP EPSILON ASSOCIATES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Overview 1-1 1.1 Introduction 1-1 1.2 Project Identification 1-3 1.3 Boston University Medical Center Mission and Objectives 1-4 1.3.1 Boston Medical Center 1-4 1.3.2 Boston University Medical Campus 1-6 1.3.2.1 Boston University School of Medicine 1-6 1.3.2.2 Goldman School of Dental Medicine 1-7 1.3.2.3 School of Public Health 1-8 1.4 Existing Campus and Facilities 1-8 1.5 Guiding Principles and Planning Assumptions 1-12 1.5.1 Shared Planning Assumptions and Objectives 1-12 1.5.2 BMC Planning Assumptions and Objectives 1-13 1.5.3 BU Medical Campus Planning Assumptions and Objectives 1-14 1.5.4 Campus Adjacencies 1-15 1.5.5 Addressing Aging Buildings 1-17 1.6 Summary of Program Needs 1-17 1.6.1 Clinical Services 1-18 1.6.2 Administrative 1-18 1.6.3 Support Operations and Infrastructure 1-18 1.6.4 Energy Service 1-18 1.6.5 Student Housing 1-19 1.6.6 Academic and Student Services 1-20 1.7 Summary of Institutional Master Plan Projects 1-20 1.8 Public -

BUSM News & Notes

Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu BU Publications BUSM News and Notes 1984-06 BUSM News & Notes: June 1984 no. 77 https://hdl.handle.net/2144/21830 Boston University News Notes Boston University School of Medicine June 1984 Issue #77 BUSM STUDY REPORTS FUNCTIONAL Patients interviewed before and after BENEFITS OF CABG SURGERY coronary artery bypass graft surgery demonstrated improvement in physical, sexual and social functioning after the surgery, according to a BUSM report in the April issue of The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. The report is based on an ongoing BUSM longitudinal study of recovery and rehabilitation after major cardiac surgery. The researchers analyzed data from standardized questionnaires and inter• views administered to 340 patients before and after their operations. After surgery, CABG patients had fewer total activity restrictions or incapacitated days per month; experienced improvement in the quality of their sexual lives through increased energy and desire, and decreased pain and worry; and were more readily able to return to work and to participate in social functions, according to the report. The study was conducted at four hospitals, including University Hospital. Researchers were Babette-Ann Stanton, Ph.D., an assistant research professor of medicine and psychiatry and acting chairman of the Department of Behavioral j^idemiology; C. David Jenkins, Ph.D., former chairman of the Department and now at the University of Texas Medical Branch; Judith A. Savageau, M.P.H., a biostatistician; and Robert L. Thurer, M.D., of the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at Beth Israel Hospital. SEYMajR KAUFMAN, RADIOLOGIST Seymour A. Kaufman, M.D., a BUSM clinical AT BUSM, UH, DIES AT AGE 58 professor of radiology for 14 years and an alumnus of the School, died unexpectedly May 28 at Beth Israel Hospital. -

Saxonville 1 Saxonville As a New Teacher to Framingham, I Was Interested to Learn That Different Areas Of

Saxonville 1 Saxonville As a new teacher to Framingham, I was interested to learn that different areas of Framingham are designated as villages. These distinct regions of Framingham emerged over time in reaction to the each area’s natural resources, the resulting ways these features were used, and the people who used them. Saxonville is perhaps the name that is still most recognizable and an interesting “artifact” to investigate. "Saxonville from Danforth Hill" — a photograph from the book Framingham Illustrated, published by Lithotype. http://www.saxonville.org/FOS%20Winter%202002b.pdf Printing Co., New York, in the late 1800s. Settler John Stone was the first settler of what became Framingham when he built his home at Otter Neck as named by the way the winding of the Sudbury River encloses the area on three sides. He had first settled in Sudbury then found that while, “There was an abundance of water and woodland for fishing and hunting… his farm land in Sudbury was marshy.” (Framingham ¶2) His new home provided him not only with all of those resources, it also allowed him to set up a corn mill as early as 1660 and he was soon joined by other settlers to the region as they increasingly replaced the established Native American tribe of Nipmucs. The region of land was initially called Saxonville 2 Danforth’s Farms after the grants of lands made to Thomas Danforth by the Colonial Government. In 1770 the town was incorporated as Framingham after Danforth’s place of birth in England, “Framlingham”, although there is no recorded reason why the “l” was dropped from the name. -

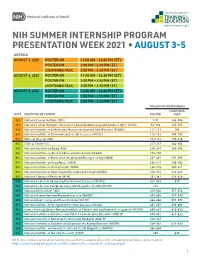

Summer Presentation Week

NIH SUMMER INTERNSHIP PROGRAM PRESENTATION WEEK 2021 • AUGUST 3-5 AGENDA AUGUST 3, 2021 POSTER AM 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM (ET) POSTER PM 1:00 PM – 2:30 PM (ET) LIGHTNING TALK 3:00 PM – 4:30 PM (ET) AUGUST 4, 2021 POSTER AM 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM (ET) POSTER PM 1:00 PM – 2:30 PM (ET) LIGHTNING TALK 3:00 PM – 4:30 PM (ET) AUGUST 5, 2021 POSTER AM 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM (ET) POSTER PM 1:00 PM – 2:30 PM (ET) LIGHTNING TALK 3:00 PM – 4:30 PM (ET) PRESENTATION NUMBERS LIGHTNING DATE INSTITUTE OR CENTER POSTER TALK 8/3 National Cancer Institute (NCI) 1-91 144-184 8/3 National Cancer Institute – Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (NCI – DCEG) 92-110 185-187 8/3 National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) 111-113 188 8/3 National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) 114-141 189-192 8/3 Office of Director (OD) 142-143 193-216 8/4 Clinical Center (CC) 217-237 362-364 8/4 National Institute on Aging (NIA) 238-247 365-396 8/4 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) 248-256 8/4 National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) 257-261 397-399 8/4 National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 262-279 400-402 8/4 National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) 280-315 403-411 8/4 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) 316-351 412-423 8/4 National Library of Medicine (NLM) 352-361 424-426 8/5 National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) 427-433 570 8/5 National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) 434 8/5 National Eye Institute