Alto Building, Queens Road, Reading, Berkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South East Hertfordshire | Oxfordshire | Buckinghamshire | Berkshire Discover Little Adventures on Your Doorstep

South East Hertfordshire | Oxfordshire | Buckinghamshire | Berkshire Discover little adventures on your doorstep Walk along the towpath and spot different types of boats Count how many water birds you can spot and name in five minutes Relax in a canalside café and watch narrowboats passing by Take a boat trip and learn more about the Oxford Canal Take a picnic and feed the ducks healthy snacks See the ruins of Berkhamsted Castle Take a fishing net and go canal dipping Cycle down the towpath and take a break at a waterside pub Watch the boats passing through the locks Check out the awesome Iron Trunk Aqueduct Banbury, Thrupp, Oxford, Cosgrove & Wolverton, Aylesbury, Tring, Western Turville Reservoir, Berkhamsted, Apsley, Cassiobury Park, Watford, Hungerford Wharf, Kintbury, Newbury, Aldermaston Wharf, Garston Lock, Reading Are you looking for inspiring places to visit with the family? Then look no further than your local canal or river. This guide features a selection of our best waterside places to visit in London – whatever the weather! Each location includes a map, suggestions of fun-packed activities you can do and useful information on where to park, places to eat, toilets and boat trips. Have a look on our map 1. Banbury and find a little 2. Thrupp adventure on 3. Oxford your doorstep! 4. Cosgrove & Wolverton 5. Tring 6. Western Turville Reservoir 7. Berkhamsted 8. Apsley 9. Cassiobury Park, Watford 10. Hungerford Wharf 11. Kintbury 12. Newbury 13. Aldermaston Wharf 14. Garston Lock 15. Reading *AINA Waterways * This map shows waterways managed by members of the Association of Inland Navigation Authorities (AINA). -

Bulletin of the Veteran Car Club of South Australia, Inc

Bulletin of the Veteran Car Club of South Australia, Inc. www.vccsa.org.au Vol. 7, No. 10 – May 2013 Chairman: Howard Filtness 8272 0594 Treasurer: Tim Rettig 8338 2590 Secretary: David Chantrell 8345 0665 Rallymaster: Phil Keane 8277 2468 Committee: Peter Allen 8353 3438 Neil Francis 8373 4992 Terry Parker 8331 3445 Public Officer Dudley Pinnock 8379 2441 Address for Correspondence: P.O.Box 193, Unley Business Centre, Unley 5061 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vccsa.org.au Bulletin editor : Tony Beaven 0407 716 162 [email protected] Some Nuriootpa Rally photos Meetings The Club holds informal gatherings at 8pm on the Wednesday 5 th June. Rob Elliott will be showing first Wednesday of each month, except January, at pictures and telling us about the wonderful car the Colonel Light Gardens RSL, enter off Dorset museums that he has visited in the U.S.. Ave. Assemble at 7.30 for a pre-meeting chat. The Wednesday 4 th July. Will be our AGM. Please only formal club meeting is the Annual General bring a small plate of supper to share. Meeting, held on the first Wednesday in July each August. We are once again looking at having a year. cinema night, similar to last years very successful Wednesday 1 st May. Anecdotes, photos and tall outing, but not sure where we will find a film as stories from our terrific weekend rally based at good as ‘The Sapphires’. Nurioopta. Bulletin May 2013 Page 1 Upcoming events McLAREN VALE BRITISH LUNCHEON SUNDAY 5 th MAY (not 12 th May as in previous Bulletin) Meet in the carpark at Coles Blackwood at 9.30 for 10am start Travel through Coromandel Valley and Clarendon to Bakers Gully Road. -

Henley and Return from Aldermaston | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Henley and return from Aldermaston Cruise this route from : Aldermaston View the latest version of this pdf Henley-and-return-from-Aldermaston-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 5.00 to 0.00 Cruising Time : 20.00 Total Distance : 37.00 Number of Locks : 28 Number of Tunnels : 0 Number of Aqueducts : 0 Cruise along the Kennet & Avon canal to the River Thames and the renowned town of Henley-on-Thames. Passing Reading you will be central for shopping or just strolling around the streets, window shopping. You may like to visit the Abbey Ruins, or perhaps Reading Gaol, made famous by Oscar Wilde, who wrote De Profundis (a letter to Lord Alfred Douglas) whilst imprisoned there in 1897, as well as the poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol. There are also a couple of museums, and gardens to relax in. You will be spoilt for choice for somewhere to eat, or to enjoy a coffee, perhaps whilst people watching, in this vibrant town. Henley-on-Thames has a pretty waterfront with moored boats. Here, you will find a market town with all facilities. There is a wealth of shops, a theatre and local services, including a launderette. The Henley Royal Regatta is held in the first week of July. Cruising Notes Day 1 If you set off this afternoon, you could travel for a couple of hours before mooring for the night. -

Reve House the Warren • Caversham • Reading • Berkshire Reve House the Warren • Caversham • Reading Berkshire • RG4 7TQ

Reve House THE WARREN • CAVERSHAM • READING • BERKSHIRE Reve House The Warren • Caversham • reading Berkshire • rg4 7TQ An exceptional riverside home Entrance hall • Drawing room • Study Dining room with wine cellar • Kitchen/Breakfast room Utility room • Family room Master bedroom with en suite and dressing room Guest bedroom with en suite 3 further bedrooms with en suite Garage with office overhead • Gardens Mooring • Private parking reading rail station 2 miles (direct trains to London Paddington 25 mins) • henley-on-Thames 8 miles London 40 miles (m4 J8/9 9 miles) • heathrow airport 30 mins Walking distance of Caversham village and reading station (all distances and timings are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Reve House This elegant five bedroom family home occupies a wonderful position on the banks of the River Thames. Reve House is a stunning newly built New England style property, offering beautiful views across the river. Built and finished to an extremely high specification with the attention to detail being second to none. This family home is arranged over three floors and benefits from under floor heating and handmade hardwood double glazed windows and doors. Internal cabling all to Category 6, 3D Pure Theatre cinema system and wireless Sonos sound system cabled throughout the house. The stunning drawing room is a focal point on the ground floor with bi-fold doors opening onto the balcony which offers magical views over the garden and the river beyond. -

Analysis of British Waterways' Waterways Condition Survey 2009

© NABO 2009 BW Waterways Condition Survey 2009 Page 1 Analysis of British Waterways' Waterways Condition Survey 2009 in association with Page 2 BW Waterways Condition Survey 2009 © NABO 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary..............................................................................................................................3 Report on NABO's BW Waterways Condition Survey 2009...............................................................5 Introduction.................................................................................................................................5 About You...................................................................................................................................5 Cruising Area..............................................................................................................................5 "In better shape than at any time in decades", or not?................................................................6 Locks...........................................................................................................................................6 Bridges........................................................................................................................................6 Cruising and Mooring.................................................................................................................7 Stoppages....................................................................................................................................7 -

Devizes to Westminster 2013 Day 1

Devizes to Westminster 2013 Day 1: Devizes to Newbury 33.65 miles & 34 portages Time Start Finish Day Planned Latest Actual 0.0 125.0 Devizes Wharf: Start 33.7 09:30 09:30 0.2 124.8 Cemetry Road Bridge [No 140] 33.5 09:32 09:33 0.3 124.7 Park Road Bridge [No 139] 33.4 09:33 09:35 0.4 124.6 A361 London Road Bridge [No 138] 33.2 09:35 09:37 0.9 124.1 Brickham Bridge [No 137] 32.8 09:40 09:46 1.0 124.0 Coate Bridge [No 136] 32.7 09:41 09:47 1.8 123.2 Laywood Bridge [No 135] 31.9 09:50 10:02 2.6 122.5 Horton Bridge [No 134] 31.1 09:59 10:15 3.0 122.0 Bishops Cannings swing Bridge [No 133] 30.7 10:04 10:23 3.2 121.8 Horton Chain Bridge [No 132] 30.5 10:06 10:27 3.7 121.3 Horton Fields swing Bridge [No 131] 30.0 10:12 10:35 3.9 121.1 Allington Bridge [No 130] 29.8 10:15 10:39 5.5 119.5 Allington swing Bridge [No 129] 28.2 10:33 11:08 5.9 119.1 Woodway Bridge [No 128] 27.8 10:38 11:15 6.1 118.9 All Cannings Bridge [No 127] 27.6 10:39 11:18 6.9 118.1 England's Bridge [No 126] 26.8 10:49 11:33 7.3 117.7 Stanton Bridge [No 125] 26.4 10:54 11:40 7.9 117.1 Honey Street Bridge [No 124] 25.8 11:00 11:50 8.2 116.8 Alton Valley Bridge [No 123] 25.5 11:04 11:56 8.8 116.2 Woodborough Fields Bridge [No 122] 24.9 11:11 12:06 9.7 115.3 Lady's Bridge [No 120] 24.0 11:21 12:22 10.2 114.8 Bowdens Bridge [No 119] 23.5 11:27 12:31 10.4 114.6 Wilcot swing Bridge [No 118] 23.3 11:30 12:35 10.6 114.4 Wilcot Bridge [No 117] 23.0 11:32 12:39 10.9 114.1 Stowell Park Suspension Bridge [No 116] 22.8 11:35 12:44 11.2 113.8 Bristow Bridge [No 115] 22.5 11:39 12:49 11.8 113.3 -

Welcome to Lazy Fox

Welcome to Lazy Fox BOATERS MANUAL Tel: 01380 828795 www.foxhangers.co.uk Contents: Page Page Medical and Emergency Contact Information 1 Boat Handling 18 Water conservation Welcome Aboard 2 Other waterway users Return time Steering, stopping & mooring Earlier return Reversing Turning round Boat Safety 3 Skipper’s Responsibilities The River Avon 20 People on deck Safety Falling overboard Moorings in Bath Fire Extinguishers Visitor moorings First Aid kit Water points Buoyancy Aids/Lifejackets Hanham lock Life-ring Bristol Utilities Onboard 5 Planning Your Route 22 Gas West of Foxhangers Carbon monoxide/smoke alarms East of Foxhangers Fresh water Hot water Warning & Advice 28 Electrical power Crofton & Bath Deep locks Ancillary switches Diesel Anti-social Behaviour 30 Central heating Reporting incidents Appliances Onboard 8 Considerate Boating 31 Refrigerator Television Good Food Guide 32 Radio/CD Player West of Foxhangers Cooker East of Foxhangers Microwave (Silver fleet) Onboard Hairdryer (supplied) Shops 37 West of Foxhangers Toilets and Waste Tanks 10 East of Foxhangers Propulsion Engine 12 Angling 39 Engine checks (daily) Navigating past people fishing Starting Fishing on the K&A Stopping Tickets & licenses Clearing the propeller Clubs & Associations Speed Limits Appendices 42 Other Information 14 Boat inventory I Rubbish/litter/recycling Heater controls II Waterway key TV & Radio instructions III CRT Boaters’ handbook IV Waterway Features 15 CRT incident forms V Swing bridges CRT Safety Alert – Cill Hang-up VI Locks CRT Quiet Zones -

Your Guide to Our Top 100 Destinations Escape to One of Our Top 100 Destinations Near You, with Our FREE, Downloadable and Printable Maps

FREE days out for all on your doorstep! Your guide to our top 100 destinations Escape to one of our top 100 destinations near you, with our FREE, downloadable and printable maps Get away from it all and enjoy quality ‘Real Time’ at our top 100 Destinations. Head online to find our FREE ‘Readymade Waterway Days’, each one has inspiring ideas for fun-packed family days out. Whether you hanker for adventure or just want to relax and soak up the scenery, you can take to the water in a canoe, cycle or walk along our towpaths. Get closer to nature and watch the wildlife or try the tranquil pleasures of fishing. You’ll find culture in our museums, plenty of places to enjoy the odd pint and a bite to eat. For great value trips download our FREE maps and activity sheets and discover a ‘Readymade Waterway Day’ in your area. canalrivertrust.org.uk/places-to-visit Download the app To download our free app ‘Places to Visit’ visit canalrivertrust.org.uk/places-to-visit or download from the App Store or Google Play™ The Tees Barrage 1 Sowerby Bridge 11 & Stockton Tuel Tunnel Lock, lock keeper, Viewing platform, take binoculars, boat hire, Wainhouse Tower, seals, water sports, boat trips, picnic area, café, pub. feed the ducks, narrowboats, picnic area, café, pub. Tees Barrage Way, Stockton-on-Tees TS17 6QA Stanley St, Sowerby Bridge HX6 2AJ Ripon 2 Standedge Tunnel 12 Bird hides, boat trips, towpath, Boat trips, Tunnel End Reservoir wildflowers, visit Ripon Cathedral, Nature Trail, visit Loft Space Creative converted canal buildings, walk down the towpath, hub, picnic area, Information Centre, play area, café. -

BOAN 2017Test

No. 34 2017 Contents Philbrick’s Tannery on Katesgrove Lane, Reading 3 Evelyn Williams Wallingford’s Malting Industry 26 David Pedgley The Berkshire Bibliography, 2017 45 Katie Amos ISSN 0264 9950 1 Berkshire Local History Association Registered charity number 1097355 President: Brian Boulter Chairman and vice-president: Mr David Cliffe Berkshire Local History Association was formed in 1976. Membership is open to individuals, societies and corporate bodies, such as libraries, schools, colleges. The Association covers the whole area of the County of Berkshire, both pre and post 1974. Editor Dr J. Brown. The editorial committee welcomes contributions of articles and reports for inclusion in forthcoming issues of the journal. Please contact Dr Jonathan Brown, 15 Instow Road, Reading, RG6 5QH (email [email protected]) for guidance on length and presentation before submitting a contribution. The editor’s judgement on all matters concerning the acceptance, content and editing of articles is final. Details of books or journals for inclusion in the bibliography section should be sent to Katie Amos, Reading Central Library, Abbey Square, Reading, RG1 3BQ. The Association would like to express its thanks to all those who helped by assisting with the various stages of producing this issue of the journal. Cover illustrations Front: Philbrick’s tannery by the Kennet and County Lock, c. 1895. Back: Inside an early nineteenth-century maltkiln. Berkshire Old and New is published by Berkshire Local History Association ©2017 Berkshire Local History Association www.blha.org.uk No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the editor. -

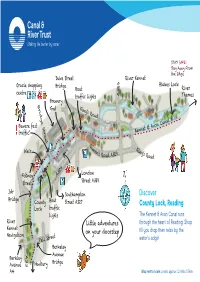

Discover County Lock, Reading

STAY SAFE: Stay Away From the Edge Duke Street River Kennet Oracle shopping Bridge Blakes Lock Boat River centre A329 traffic lights Thames Bridge Street Brewery Gut Kin g’s Road al Can Beware fast Avon ennet & traffic! K Qu Weir ee Kin n’s 9 g’s Road A32 Road Fobney A329 London Street Street A329 Discover Idr Southampton Bridge County Boat Street A327 County Lock, Reading traffic Lock The Kennet & Avon Canal runs lights through the heart of Reading. Shop River Little adventures Kennet till you drop then relax by the on your doorstep Navigation reet water’s edge! Pell St Berkeley A33 Avenue Berkley Avenue Newbury Bridge covers approx 1.2 miles/1.9km A4 Map not to scale: A little bit of history The Kennet & Avon Canal was once the main trading route from Bristol to London. The canal bought great prosperity to Reading and saw industries such as brewing, sawmilling and biscuit-making thrive. Simond’s Brewery once occupied the land around the lock. Today, it’s a great place to watch boats. Best of all it’s FREE!* ve thi Fi ngs to d o at C ounty Go shopping in the Oracle Shopping Loc Centrek, Rea anddin g keep an eye open for boats passing through! Information The Oracle Shopping Huntley & Palmer used the canal to transport Centre biscuits from its factory here. Visit Reading Reading RG1 2AG Museum and see an amazing collection of old biscuit tins. Parking (pay & display) Spot the traffic lights for boats. Check out the amazing weir at County Lock. -

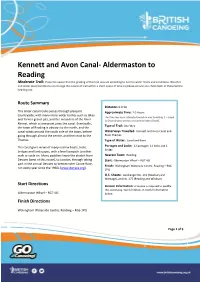

Kennett and Avon Canal- Aldermaston to Reading Moderate Trail: Please Be Aware That the Grading of This Trail Was Set According to Normal Water Levels and Conditions

Kennett and Avon Canal- Aldermaston to Reading Moderate Trail: Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Route Summary Distance: 9 miles This linear canal route passes through pleasant Approximate Time: 2-3 Hours countryside, with many more water bodies such as lakes The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph and former gravel pits, and the meanders of the River (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Kennet, which at one point joins the canal. Eventually, Type of Trail: One Way the town of Reading is obvious to the north, and the canal winds around the south side of the town, before Waterways Travelled: Kennett and Avon Canal and going through almost the centre, and then east to the River Thames Thames. Type of Water: Canal and River The canal gives views of many narrow boats, locks, Portages and Locks: 12 portages- 11 locks and 1 bridge bridges and landscapes, with a level towpath to either walk or cycle on. Many paddlers know the stretch from Nearest Town: Reading Devizes (west of this route), to London, through taking Start: Aldermaston Wharf – RG7 4JS part in the annual Devizes to Westminster Canoe Race, Finish: Wokingham Waterside Centre, Reading – RG6 run every year since the 1960s (www.dwrace.org). 1PQ O.S. Sheets: Landranger No. 174 (Newbury and Wantage), and No. -

KENNET VALLEY STUDY • READING - THEALE F I N a L Re P Or T • J U N E 19 8 7

Th a m es W a t e r River s Di vi s i on KENNET VALLEY STUDY • READING - THEALE F i n a l Re p or t • J u n e 19 8 7 • • • • • • SIR ALEXANDER GI BB & PARTNERS i n a ss oc i a t i on wi t h I NSTITUTE OF HYDROLOGY • T h a mes W a t er • R iver s Div i s i on KENNET VALLEY STUDY . READING - THEALE F i n a l Rep or t • J u n e 198 7 • • • • • • • SI R ALEXANDER GI BB & PARTNERS in a s soci a t i on wi t h I NSTITUTE OF HYDROLOGY • S I R A L EXA ND E R G I B B & PA RT N ER S EA RLEY HO US E C O N S U L T I N G E N G I N E E R S 4 27 LO N DO N ROA D EA RLEY P • R T N E R S • S E N I O R C O N S U L T A N T S R EADI NG RG6 IB L 0 14 C O AT E S W M • E• • n c t F. S • N on g • 0 15S E • • s C E K P . S C O TT m c r En n o t n o E N Z L L L L L L o w l 0 7 3 4 - 0 10 6 1 ( I S L I N E S ) v C O R N ET m• n e e r i B .