Ecological Integrity of National Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bathurst Fact Sheet

Qausuittuq National Park Update on the national park proposal on Bathurst Island November 2012 Parks Canada, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) and the community of Resolute Bay are working together to create a new national park on Bathurst Island, Nunavut. The purpose of the park is to protect an area within the The park will be managed in co-operation with Inuit for Western High Arctic natural region of the national park the benefit, education and enjoyment of all Canadians. system, to conserve wildlife and habitat, especially areas It is expected that the park’s establishment will enhance important to Peary caribou, and enable visitors to learn and support local employment and business as well as about the area and its importance to Inuit. help strengthen the local and regional economies. Qausuittuq National Park and neighbouring Polar Bear Within the park, Inuit will continue to exercise their Pass National Wildlife Area will together ensure protec - right to subsistence harvesting. tion of most of the northern half of Bathurst Island as well as protection of a number of smaller nearby islands. Bringing you Canada’s natural and historic treasures Did you know? After a local contest, the name of the proposed national park was selected as Qausuittuq National Park. Qausuittuq means “place where the sun does - n't rise” in Inuktitut, in reference to the fact that the sun stays below the horizon for several months in the winter at this latitude. What’s happening? Parks Canada and Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) are working towards completion and rati - fication of an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agree - ment (IIBA). -

Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan

Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan Options and Recommendations Draft – 2014 Contents Introduction .............................................................................. 3 Aerodromes ................................................................................ 75 Purpose ........................................................................................... 3 DND Establishments ............................................................... 76 Guiding Policies, Objectives and Goals ............................... 3 North Warning System Sites................................................ 76 Considered Information ............................................................ 3 Encouraging Sustainable Economic Development ..... 77 Decision making framework .................................................... 4 Mineral Potential ...................................................................... 77 General Options Considered .................................................... 4 Oil and Gas Exploration .......................................................... 78 Protecting and Sustaining the Environment .................. 5 Commercial Fisheries .............................................................. 78 Key Migratory Bird Habitat Sites .......................................... 5 Mixed Use ............................................................................... 80 Caribou Habitat ......................................................................... 41 Mixed Use .................................................................................. -

“1—ULUR-La Issuing Authorities and Terms and Conditions

PARKS CANADA AGENCY RESEARCH AND COLLECTION PERMIT (NOT TRANSFERABLE) PERMIT No.: 2019-31417 START DATE: 2019-04-01 EXPIRY DATE: 201 9-07-31 Project Title: Wolf predation and Peary caribou population composition on the Bathurst Island Complex Principal Investigator Name: Conor Mallory Address: P0 Box 209 Iglulik, NU, Canada XOA OLO Telephone: 867-934-2175 Email: [email protected] Affiliation: Government of Nunavut, Department of Environment Is hereby authorized to conduct the research project entitled “Wolf predation and Peary caribou population composition on the Bathurst Island Complex”, Research and Collection Permit Application Number 37401, In Qausuittuq National Park of Canada, subject to the terms and conditions set out below and/or attached to and forming part of this Research and Collection Permit. Members of Research Team: 1. Matt Fredlund, Government of Nunavut Department of Environment. Iglulik, NU. (867) 934-2176. mfredIund(äqov.nu.ca 2. Dan MacNulty, Utah State University. 5230 Old Main Hill, Logan, Utah 84322-5230 U.S.A. (435) 797-7442. [email protected]. 3. Morgan Anderson, Government of British Columbia. Prince George, BC. (250) 953- 0413. Morqan.anderson(qov.bc.ca. 4. Peter Eckalook, Resolute Bay, Nunavut 5. The Principal Investigator will contact the Research Coordinator (contact details below) if there are any changes to field team members before any new field team member enters the park. ( ‘\ç’J P-’ ULUR-lA Issuing Authorities and Terms and Conditions: “1— Permit issued pursuant to: National Parks General Regulations: Section(s) 7(5)11(1) National Parks Wildlife Regulations: Section 15(1)(a) Parks Parcs I+1 Canada Canada Canad Conditions identified in the NIRB Screening Decision Report No. -

Poole Resume

Kim Poole, M.Sc., RPBio Certified Wildlife Biologist Aurora Wildlife Research 1918 Shannon Point Rd., Nelson, BC V1L 6K1 Tel: (250) 825-4063; Fax: (250) 825-4073 e-mail: [email protected] Professional Profile Current Position: Aurora Wildlife Research – Owner and Senior Wildlife Biologist since 2000. Kim is a professional biologist (Registered Professional Biologist; RPBio) and Certified Wildlife Biologist (The Wildlife Society) with 33 years of experience in public and private sectors throughout western Canada, with extensive experience in the NWT/Nunavut and British Columbia. Fifteen years of work on a variety of species with the NWT government and 18 years as an independent consultant have provided Kim with a broad range of skills and experiences. Kim has demonstrated expertise in the areas of wildlife inventory and wildlife habitat assessment, and identification, mitigation and monitoring of environmental impacts related to the mining, forestry, and tourism industries. Since 2004 Kim has led and designed baseline studies as well as 3rd party reviews for a number of environmental impact assessments in NWT, Nunavut and British Columbia. He has experience conducting and leading research and management studies on species such as moose, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, mule deer, elk, caribou, muskoxen, grizzly bears, furbearers, and raptors. Kim has strong experience in study design, data analysis, and report writing, as demonstrated in authorship in over 50 refereed journal articles and well over 100 technical reports. Education -

Caribou Wintering

Written Submission No. 06 2016 Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan Proposed Land Use Designation: Community Areas of Interest – Caribou Wintering To: The Nunavut Planning Commission From: The Qikiqtaaluk Wildlife Board (QWB), and the Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTOs) of Arctic Bay and Resolute Bay Background Information: Caribou is a keystone species for the maintenance of Inuit culture and well-being, as well as for the northern ecosystem. Arctic tundra Caribou are known to go through long-term cycles, with each cycle lasting up to the entire lifetime of an elder (Ferguson et al. 1998). In the High Arctic, population fluctuations usually occur over shorter time periods, and are sometimes mediated by especially severe foraging conditions during some winters. During these population fluctuations and cycles, there are decades when caribou are in low abundance, and they are very sensitive to disturbance by humans. Unlike large populations of caribou, small ones are not resilient to disturbance, loss of habitat, and human disturbance and development that may separate them from their seasonal habitats. The protection of important areas for caribou during these decades is critically important, or the populations may never return to their former abundance, and their natural recovery and cycles could be lost. The 2016 draft Nunavut Land Use Plan (NLUP) claimed that there is insufficient information for caribou-specific land use designations, except on the mainland of Nunavut. The QWB believes that this is not true, given the extensive Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) that was shared with NPC and governments by Inuit of Qikiqtaaluk communities in the past, and peer-reviewed papers already published about caribou in Qikiqtaaluk Region. -

April 1, 1999 Nunavut Becomes a Separate Territory

April 1, 1999 Nunavut Becomes a Separate Territory Nunavut is one of the territories of the Dominion of Canada. It is located in the far north and is considered to be part of the Arctic region. It has long, cold winters and short, cool summers. Nunavut makes up about one-fifth of the land area of Canada and is an important source of natural resources including diamonds, copper, gold, silver, and uranium. It is made up of rocky, treeless areas, and a lot of the ground is permanently frozen. There are large areas of Nunavut that are protected areas, including five national parks that attract the more adventurous visitors. Others are attracted to the exploring, fishing, hunting, and other outdoor activities. Look at the map of Nunavut below. Label the capital of Nunavut. Locate the towns of Eureka, Alert, Resolute, Qikiqtarjuaq, Kimmirut, Cape Dorset, Arviat, Kuglugtuk, and Carmacks, and label them on the map. Now label the United States Range and Mount Barbeau. Also, locate the Back River, Thelon River, Contwoyto Lake, Garry Lake, Yathkyed Lake, Kasba Lake, and Neultin Lake, and label them. Now, label Foxe Channel, Foxe Basin, Queen Maud Gulf, Gulf of Boothia, Nansen Sound, Coronation Gulf, M’Clintock Channel, Jones Sound, Parry Channel, and Lancaster Sound. Lastly, label the provinces, territories, states, or major bodies of water that border Nunavut. When you have finished, move on to the timeline of Nunavut history on the next page and the research prompts that follow. ©2018 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com Timeline of Nunavut History Answer Key c. 1000 1576 1670 1771 1847 1876 1880 1930 1950 1955 1979 1982 1988 1992 1993 1999 2001 2003 2014 2015 ©2018 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com 1. -

(Qausuittuq National Park) Order Décret Déclarant I

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Withdrawal from Disposal of Décret déclarant inaliénables Certain Tracts of Territorial certaines parcelles territoriales Lands in Nunavut (Qausuittuq au Nunavut (parc national National Park) Order Qausuittuq) SI/2014-109 TR/2014-109 Current to September 22, 2021 À jour au 22 septembre 2021 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Page 1 of 2 SUBMISSION to the NUNAVUT WILDLIFE

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: Decision: X Issue: Downlisting of Peary Caribou from Endangered to Threatened. Background: In October 2016 the Committee on the Status of Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) provided a re‐ assessment of Peary Caribou to the federal Minister of the Environment. This begins the formal listing process under the federal Species at Risk Act. Peary Caribou, which are currently listed under the federal SARA as Endangered, have been re‐assessed by COSEWIC in a lower risk category as Threatened. A recovery strategy is required for both Endangered and Threatened species. If Peary Caribou are downlisted under the federal SARA, a recovery strategy will still be required and it will not affect the current recovery strategy development process currently underway for Peary Caribou GN - Morgan Anderson Community consultations on the proposed downlisting of Peary Caribou were held with hunters and trappers organizations (HTOs) and regional wildlife boards in the range of Peary Caribou between June and August 2017. Organizations were asked to provide their formal position on the proposed downlisting and with any other comments, concerns or information that they feel should be considered. Consultation packages, in Inuktitut and English, were sent by mail and email. They included: a letter, information on the assessment and a questionnaire/response form. Follow‐up calls to the HTOs and RWBs were made on September 27, 2017. Results of Consultation: Kitikmeot Regional Wildlife Board No response -

2016-2017-QIA-Annual Report

2016-17 ANNUAL REPORT Protecting and Promoting Inuit Rights and Values Igluvut Building, 2nd Floor PO Box 1340 Iqaluit, NU X0A 0H0 867-975-8400 1-800-667-2742 [email protected] www.qia.ca About Qikiqtani Inuit Association The Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) is a not-for-profit society which represents approximately 14,000 Inuit in the Qikiqtani (Baffin) Region of Nunavut, including 13 communities from Grise Fiord in the High Arctic to Sanikiluaq (Belcher Islands) in the southeast of Hudson Bay. QIA’s mission is to safeguard, administer and advance the rights and benefits of the Qikiqtani Inuit; and to promote Inuktitut and Inuit traditions, environmental values, self-sufficiency, and economic, social and cultural well-being in an open and democratic forum. Under Article 39 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, QIA is considered a Designated Inuit Organization (DIO) responsible for managing Inuit Owned Lands in the Qikiqtani Region. QIA is one of three Regional Inuit Associations affiliated with Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI). The other two Regional Inuit Associations are the Kitikmeot Inuit Association and the Kivalliq Inuit Association. QIA works closely with its partners and all levels of governments to ensure that Inuit are being adequately served. Two other organizations operate under the QIA umbrella: Kakivak Association, which is responsible for community economic development and small businesses; and Qikiqtaaluk Corporation, which manages economic development on behalf of QIA. Kakivak is QIA’s community economic QC strives to be a major contributor to all development organization and small business sectors of the Nunavut economy, focusing arm. Kakivak’s mandate is to help Qikiqtani primarily on fisheries, retail operations, property Inuit own and develop their businesses by development and management. -

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0014; 4500030113]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7571/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2019-0014-4500030113-4827571.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0014; 4500030113]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/31/2021 and available online at Billing Code 4333-15 federalregister.gov/d/2021-18098, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0014; 4500030113] RIN 1018–BD03 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Status with Section 4(d) Rule for the Dolphin and Union Caribou and 12-month Finding for the Peary Caribou AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Proposed rule; 12-month finding. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, announce a 12-month finding on a petition to list the Peary caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) (a caribou subspecies) and the Dolphin and Union caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus × peary) as endangered or threatened subspecies under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). Both Peary caribou and Dolphin and Union caribou are native only to Canada. After a review of the best available scientific and commercial information, we find that it is not warranted at this time to add the Peary caribou to the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. We find that listing the Dolphin and Union caribou as a Distinct Population Segment (DPS) of the barren-ground caribou subspecies (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) is warranted. Accordingly, we propose to list this DPS with a rule issued under section 4(d) of the Act (“4(d) rule”). To ensure that subsequent rulemaking resulting from this proposed rule is as accurate and effective as possible, we are soliciting information from the public, other governmental agencies, the Government of Canada and its provincial governments, the scientific community, industry, and any other interested parties. -

DISTRIBUTION and ABUNDANCE of PEARY CARIBOU (Rangifer Tarandus Pearyii) and MUSKOXEN (Ovibos Moschatus) on the BATHURST ISLAND GROUP, MAY 2013

DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE OF PEARY CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus pearyii) AND MUSKOXEN (Ovibos moschatus) ON THE BATHURST ISLAND GROUP, MAY 2013 NWRT PROJECT 2-13-18 MORGAN ANDERSON WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST, HIGH ARCTIC REGION Submitted in partial fulfillment of funding conditions to the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board September 11, 2014 NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT WILDLIFE RESEARCH SECTION IGLOOLIK, NU i Summary A survey of the Bathurst Island Group (Bathurst Island Complex [Bathurst, Helena, Cameron, Vanier, Massey, Alexander islands], and Little Cornwallis and Cornwallis islands) was flown by Twin Otter in 42 hours between May 13 and May 27, 2013 to update the population estimate for caribou and muskoxen on the island group. The populations of both species declined precipitously in the late 1990s after a series of severe winters and groundfast ice reduced forage availability. The last survey, in 2001-2002, indicated very minor recovery. Residents of Resolute Bay have reported increasing caribou and muskox populations for several years and requested an updated population estimate. This survey confirmed what residents reported. Caribou were concentrated around Bracebridge Inlet and on Massey and Alexander islands. We observed 559 caribou in total and estimate a population of 1482±387 (95% CI) caribou on Bathurst and its satellite islands. Estimates were not derived for Little Cornwallis and Cornwallis islands, although we saw 1 caribou off-transect on Little Cornwallis Island and another group of 2 caribou off-transect on Cornwallis Island, as well as fresh tracks. This is much higher than the 2001 estimate of 187 (104-330, 95% CI) caribou on the BIC and 2002 estimate of none on Little Cornwallis and Cornwallis islands. -

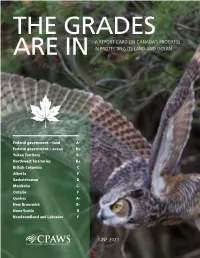

The Grades Are In: a Report Card on Canada's Progress in Protecting Its Land and Ocean

THE GRADES A REPORT CARD ON CANADA’S PROGRESS ARE IN IN PROTECTING ITS LAND AND OCEAN Federal government – land A- Federal government – ocean B+ Yukon Territory B- Northwest Territories B+ British Columbia C Alberta F Saskatchewan D Manitoba C- Ontario F Quebec A- New Brunswick B- Nova Scotia B Newfoundland and Labrador F JUNE 2021 THE GRADES ARE IN CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 I. Introduction 8 Grading Criteria 12 II. Results 16 III: What We Have Learned: Key Takeaway Messages 26 Cover photo Richard Lee IV. Assessment 30 Federal government – Land 31 Federal government – Ocean 36 Yukon Territory 40 Northwest Territories 42 British Columbia 44 Alberta 46 Saskatchewan 48 Manitoba 50 Ontario 52 Quebec 54 New Brunswick 56 Nova Scotia 58 Newfoundland and Labrador 60 Prince Edward Island 62 Nunavut 64 V. Literature Cited 66 2 Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Photo Neil Rosenstech Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society 3 THE GRADES ARE IN he Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) has conducted an assessment of how well Canada fared in delivering on a promise that dates back to 2010: to protect at least 17% of its land and 10% of its ocean by 2020. This report card presents our key findings. It assigns grades to the current federal, provincial, and territorial governments based on their contributions and highlights major achievements and shortcomings. TOur goal in producing this report card is to learn from the successes and failures of the past decade to inform more effective conservation action moving forward. Using this report as a baseline, we plan to release subsequent report cards to track progress made by each jurisdiction towards the 2025 and 2030 targets of protecting 25% of land and ocean and 30% of land and ocean, respectively.