Laughing at the Great King: Ottomans As Persians in Minato's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

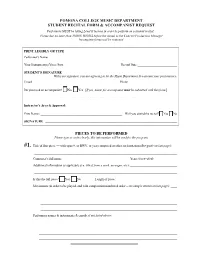

Student Recital/Accompanist Request Form

POMONA COLLEGE MUSIC DEPARTMENT STUDENT RECITAL FORM & ACCOMPANIST REQUEST Performers MUST be taking Level II lessons in order to perform on a student recital. Forms due no later than THREE WEEKS before the recital to the Concert Production Manager Incomplete forms will be returned. PRINT LEGIBLY OR TYPE Performer’s Name:__________________________________________________________________________________ Your Instrument(s)/Voice Part: Recital Date: _________________________ STUDENT’S SIGNATURE _________________________________________________________________________ With your signature, you are agreeing to let the Music Department live-stream your performance. Email _____________________________________________________ Phone ______________________________ Do you need an accompanist? •No •Yes [If yes, music for accompanist must be submitted with this form.] ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Instructor’s Area & Approval: Print Name: ____________________________________________________ Will you attend the recital? •Yes •No SIGNATURE ____________________________________________________________________________________ PIECES TO BE PERFORMED Please type or write clearly, this information will be used for the program. #1. Title of first piece — with opus #, or BWV, or year composed or other such notation (See guide on last page): ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Composer’s full name: _________________________________________ Years (born–died): ______________ -

479 7542 Fagiolihandel Ebooklet.Indd

FRANCO FAGIOLI HHANDELANDEL AARIASRIAS IL POMO D’ORO | ZEFIRA VALOVA FRANCO FAGIOLI HHANDELANDEL AARIASRIAS IL POMO D’ORO | ZEFIRA VALOVA 2 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) ORESTE RODELINDA, REGINA DE’ LONGOBARDI Libretto after Giangualberto Barlocci Libretto: Nicola Francesco Haym First performance: London, Covent Garden Theatre, 18 December 1734 First performance: London, King’s Theatre, 13 February 1725 A “Agitato da fiere tempeste” (Oreste) 4:24 I “Pompe vane di morte” (Bertarido) 2:53 J “Dove sei, amato bene?” (Bertarido) 6:19 SERSE Libretto after Silvio Stampiglia and Nicolò Minato GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO First performance: London, King’s Theatre, 15 April 1738 Libretto: Nicola Francesco Haym B “Frondi tenere e belle” (Serse) 0:47 First performance: London, King’s Theatre, 20 February 1724 C “Ombra mai fu” (Serse) 3:24 K “Se in fiorito, ameno prato” (Cesare) 8:40 D “Crude furie degl’orridi abissi” (Serse) 3:55 ARIODANTE Libretto after Antonio Salvi RINALDO First performance: London, Covent Garden Theatre, 8 January 1735 Libretto: Giacomo Rossi L First performance: London, Queen’s Theatre, 24 February 1711; “Scherza, infida, in grembo al drudo” (Ariodante) 11:13 rev. version: London, King’s Theatre, 6 April 1731 M “Dopo notte atra e funesta” (Ariodante) 7:28 E “Cara sposa, amante cara” (Rinaldo) 8:48 F PARTENOPE “Venti, turbini, prestate” (Rinaldo) 4:06 Libretto after Silvio Stampiglia IMENEO First performance: London, King’s Theatre, 24 February 1730 Libretto after Silvio Stampiglia N “Ch’io parta?” (Arsace) 4:14 First performance: -

Al Lampo Dell'armi

AMERICAN BACH SOLOISTS 1685 & The Art of Ian Howell 1 Salve Regina (1756) . Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) 2 - 6 Vergnügte Ruh’, beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170 (1726) . .Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Debra Nagy, oboe d’amore - Corey Jamason, organ Carla Moore & Cynthia Roberts, violins - Katherine Kyme, viola William Skeen, violoncello - Steven Lehning, violone — Intermission — Arias from Opera and Oratorio . George. Frideric Handel (1685-1759) 7 “O Lord, whose mercies numberless” from Saul, HWV 53 (1738) 8 “Cara sposa, amante cara” from Rinaldo, HWV 7a (1711/1731) 9 “Va tacito e nascosto” from Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17 (1724) Lawrence Ragent, natural horn bl “Frondi tenere e belle…Ombra mai fu” from Serse, HWV 40 (1738) bm “Ah, Stigie larve!…Vaghe pupille” from Orlando, HWV 31 (1732) bn “Al lampo dell’armi” from Giulio Cesare in Egitto,HWV 17 (1724) Violin Viola Oboe & Oboe d’amore Cynthia Roberts (leader) David Daniel Bowes Debra Nagy Lorenzo and Tomaso Carcassi, Florence, 1760. Richard Duke, London, circa 1780. Randy Cook, Basel, 2004; after Jonathan Bradbury, London, circa 1720. Tekla Cunningham Katherine Kyme Sand Dalton, Washington; after Johann Heinrich Johannes Ulricus Eberle, Prague, 1807. Anonymous German, 18th century. Eichentopf, Leipzig, circa 1720. Andrew Fouts Adam LaMotte Marianne Pfau Claude Pierray, Paris, circa 1710. Marco Unelli, 2001, Cremona; after Antonio B. Schermer, Basel, 2001; after Bradbury, circa Stradivari, Cremona, 1693. Cynthia Freivogel 1720. Johann Paul Schorn, Salzburg, 1715. Aaron Westman Dmitry Badiarov, Brussels, 2003; after Antonio Carla Moore Bagatella, Padua, circa 1750. Natural Horn Johann Georg Thir, Vienna, 1754 Lawrence Ragent Janet Strauss Lowell Greer, Michigan, 1981; after Anonymous Matthias Joannes Koldiz, Munich, 1733. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXXII, Number 1 Spring 2017 AMERICAN HANDEL FESTIVAL 2017: CONFERENCE REPORT Carlo Lanfossi This year, Princeton University (Princeton, NJ) hosted the biennial American Handel Festival on April 6-9, 2017. From a rainstorm on Thursday to a shiny Sunday, the conference unfolded with the usual series of paper sessions, two concerts, and a keynote address. The assortment of events reflected the kaleidoscopic variety of Handel’s scholarship, embodied by a group of academics and performers that spans several generations and that looks promising for the future of Handel with the exploration by Fredric Fehleisen (The Juilliard School) studies. of the network of musical associations in Messiah, highlighting After the opening reception at the Woolworth Music musical-rhetorical patterns through Schenkerian reductions Center, the first day of the conference was marked by the Howard and a request for the audience to hum the accompanying Serwer Memorial Lecture given by John Butt (University of harmony of “I know that my Redeemer liveth.” Finally, Minji Glasgow) on the title “Handel and Messiah: Harmonizing the Kim (Andover, MA) reconstructed an instance of self-borrowing Bible for a Modern World?” Reminding the audience of the in the chorus “I will sing unto the Lord” from Israel in Egypt, need to interrogate the cultural values inherent to the creation tracing the musical lineage to the incipit of the English canon of Messiah, Butt structured his keynote address around various “Non nobis, Domine” through its use in the Cannons anthem topics and methodologies, including an analysis of Handel’s Let God Arise and the Utrecht Te Deum. -

Duo Repertoire List

(Leos Strings Duo) Leos Strings: The Duo We can arrange most pieces of music for string duo if given enough notice and for a small fee. Classical Collection Arne Amoroso Bach: Air on G String Andante from Brandenburg No. 2 Arioso Bist du Bei Mir Gigue from Suite No 3 Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring March in D March, Chorale & Musette from Anna Magdalena Notebook 5 Menuets from Anna Magdalena Notebook My Heart Ever Faithful Rondeau Sheep May Safely Graze Watchet Auf Beethoven Ode to Joy I. Berlin Alexander’s Ragtime Band Boccherini Minuet Boyce March Brahms: Lullaby Variations on a Theme of Haydn Sicilienne St Anthony Chorale www.leos-strings.com (Leos Strings Duo) Byrd Pavane for the Earl of Salisbury Charpentier Te Deum: Prelude & Tu Devicto Chopin: Nocturne Op 9 No 2 Grande Valse Brilliante (Eb major) Clarke: Trumpet Tune Trumpet Voluntary The Prince of Denmark’s March Clementi Sonatina in C Corelli: Sarabande Pastorale Couperin Le Petit Rien Soeur Monique De Capua O Sole Mio Delibes: Flower Duet Valse Lente from Coppelia Dvorak Humoresque Elgar: Chanson de Matin Salut D’Amour Faure Pavane Gilbert & Sullivan I’m Called Little Buttercup Never mind the why and wherefore As some Day It May Happen Willow, Tit-Willow A Magnet Hung In a Hardware Shop I am the very model of a modern major general Poor Wandering One Grieg Morning’ from Peer Gynt Last Spring Hardy Anne’s Theme from Anne of Green Gables www.leos-strings.com (Leos Strings Duo) Handel: Allegro from Sonata in F Major Arrival of the Queen of Sheba La Rejouissance March from Scipio Movements -

Jaroussky Dazzles in Arias Raised from Opera's Splendid Shipwrecks

Jaroussky dazzles in arias raised from opera’s splendid shipwrec... http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/arts/music/jaroussky-da... Music: concert review Jaroussky dazzles in arias raised from opera’s splendid shipwrecks robert everett-green From Thursday's Globe and Mail Published Wednesday, Nov. 02, 2011 6:00PM EDT Philippe Jaroussky & Apollo’s Fire At Koerner Hall In Toronto on Tuesday A friend was buying tickets over the phone for a Canadian Opera Company performance when the salesperson issued a warning: “You do realize, sir, that this production features two countertenors?” That was several years ago. If acceptance of the countertenor voice has advanced since then, it’s largely because of the advent of really excellent singers in that high male range, so useful in the numerous baroque opera roles written for castrati. Philippe Jaroussky is a 32-year-old French countertenor who has quickly made a splash in 18th-century music, and also in more recent things: His latest discs include music by Gabriel Fauré, Jules Massenet and Reynaldo Hahn. The only warning that might have been posted at his Toronto debut performance was that encores would be limited to three, and not the dozen or so that his audience seemed to want. His gifts would be exceptional in any range. He sang with a pure and focused sound, incredible virtuosity, and a kind of lyrical intelligence that brought new depth to even the simplest of melodic lines. His program, with the Cleveland period-performance ensemble Apollo’s Fire, consisted of arias raised from the splendid shipwrecks of mostly obscure opera seria by Handel and Vivaldi. -

“Nunca Una Sombra Fue Más Querida”: Largo O Larghetto, El Tempo En Ombra Mai Fu

Proyecto: A través del tiempo “Nunca una sombra fue más querida”: Largo o Larghetto, el tempo en Ombra mai fu “Que truenos, relámpagos y tempestades no turben nunca vuestra querida paz” “Ombra mai fu” es una pieza para voz solista y conjunto instrumental, un arioso empleado al inicio de la ópera italiana Jerjes [Serse, Xerxes]. Compuesta entre el 26 de diciembre de 1737 y el 14 de febrero de 1738, fue estrenada en el King’s Theatre, el Teatro del Rey en Haymarket, en Londres el 15 de abril de 1738. Fue un fracaso, y tras cinco representaciones pasó a engrosar el numeroso grupo de obras a olvidar. Händel fue un compositor exitoso en distintos periodos de su carrera, pero también sufrió muchas dificultades. Así, esta obra se encuentra dentro del repertorio no apreciado en su momento. Figura 1. Portada del libreto de la ópera Xerxes compuesta por Georg Friedrich Händel, HWV 40, e impresa por J. Chrichley, Londres. En Wikimedia Commons (dominio público): <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serse#/media/File:Georg_Friedrich_H%C3%A4ndel_- _Serse_-_title_page_of_the_libretto_-_London_1738.png>; Figura 2. Georg Friedrich Händel por Thomas Hudson, 1741, Hamburgo, colección de la Biblioteca estatal y universitaria Carl von Ossietzky. En Wikimedia Commons (dominio público): <https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Friedrich_Händel#/media/Archivo:Georg_Friedrich_Händel.jpg>; Figura 3. King’s Theatre en Haymarket, por artista desconocido. En Wikimedia Commons (dominio público): <https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Friedrich_Händel#/media/Archivo:Italian_Opera_House_at_the_Haymarket_(colour).jpg> Si bien tuvo alguna valoración positiva, lo cierto es que el público no comprendió la obra. Una excepción fue la opinión de Lord Shaftesbury: “ Xerxes es más allá de toda duda una bella composición […] Mi propio juicio es que es una ópera magistral”. -

Handel Serse

HANDEL SERSE Anna Stéphany . Rosemary Joshua . David Daniels Hilary Summers . Joélle Harvey . Brindley Sherratt . Andreas Wolf Early Opera Company CHANDOS early music CHRISTIAN CURNYN HANDEL SERSE G E O RGE F R ID ER IC HAND E L Marble sculpture, 1738, by Louis-François Roubiliac (c. 1702 – 1762), now at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London / AKG Images, London George Frideric HANdel (1685–1759) Serse, HWV 40 (1737 – 38) Opera in Three Acts On an anonymous revision of the libretto Il Xerse (Rome, 1694) by Silvio Stampiglia (1664 – 1725), in turn based on the libretto Il Xerse (Venice, 1655) by Count Nicolò Minato (c. 1630 – 1698) Performing edition prepared by Peter Jones Serse, King of Persia .................................................. Anna Stéphany mezzo-soprano Arsamene, his brother, in love with Romilda................David Daniels counter-tenor Amastre, heiress to the kingdom of Tagor, betrothed to Serse ........................................................................Hilary Summers contralto Ariodate, a prince, vassal to Serse ..................................................Brindley Sherratt bass Romilda, his daughter, in love with Arsamene ................Rosemary Joshua soprano Atalanta, her sister, secretly in love with Arsamene ...................Joélle Harvey soprano Elviro, servant of Arsamene ....................................................Andreas Wolf bass-baritone Setting: Abydos, Persia in ancient times Early Opera Company Christian Curnyn 5 COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page 1 1 Ouverture. [ ] – Allegro – Adagio – Gigue 5:33 p. 82 Act I 2 2 Accompagnato. Serse: ‘Frondi tenere, e belle’ 0:41 p. 82 3 3 Aria. Serse: ‘Ombra mai fu’. Larghetto 2:21 p. 82 4 4 Recitativo. Arsamene: ‘Siam giunti, Elviro...’ 0:22 p. 83 with Elviro 5 5 Sinfonia e Recitativo. Arsamene: ‘Sento un soave concento’. Larghetto 1:49 p. -

Megan Shoen Senior Recital Program

PROGRAM I. “Se Florindo è fedele” Alessandro Scarlatti (1680-1725) “Se tu m’ami” Alessandro Parisotti (1853- 1913) “Caro mio ben” Giuseppe Giordani (1743- 1798) “Ombra mai fu” (Serse) George Fredric Handel (1685- 1759) II. “Als Luise Briefe” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756- 1791) Gabriele Von Baumberg (1766- 1839) “Minnelied” Felix Mendelssohn (1809- 1847) “Vergebliches Ständchen” Johannes Brahms (1833- 1897) “Élégie” Jules Massenet (1842- 1912) “Quia Respexit” (Magnificat) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685- 1750) “Ave Maria” Charles Gounod (1818- 1893) III. “Laurie’s Song” (The Tender Land) Aaron Copland (1900- 1990) “Must The Winter Come So Soon” (Vanessa) Samuel Barber (1910- 1981) “I Have Been Wandering” (Wuthering Heights) Bernard Herrman (1911- 1975) Charlotte Brontë (1818- 1855) “Come Ready And See Me” Richard Hundley (1931- 2018) James Purdy (1914- 2009) “I Bought Me A Cat” (Old American Songs) Aaron Copland (1900- 1990) IV. “One Hundred Easy Ways” (Wonderful Town) Leonard Bernstein (1918- 1990) “Someone To Watch Over Me” George Gershwin (1898- 1937) “Far From The Home I Love” (Fiddler On The Roof) Sheldon Harnick (1924- ) Jerry Bock (1928- 2010) “Till There Was You” (The Music Man) Meredith Wilson (1902- 1984) “Hold On” (The Secret Garden) Marsha Norman (1947- ) Lucy Simon (1943- ) “Migratory V” (Myths And Hymns) Adam Guettel (1964- ) Se Florindo è fedele “Se Florindo è fedele” was composed in 1698 by Alessandro Scarlatti (1680- 1725), an Italian composer from the Baroque Period, best known for his operas and chamber cantatas. In total, he composed over forty operas and nine oratorios, including early operatic works such as “Il Pompeo” and “Gli equivoci nel sembiante”. -

Alcina Comes from the Epic Poem Orlando Fusioso (1532), Or Quite Literally “Orlando’S Frenzy,” by the Italian Poet Ludovico

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Angelika and Medor. Scene From Orlando Furioso by Mihael Stroj (1803–1871) A Timeless Tale by Rachel Silverstein The story of Handel’s Alcina comes from the epic poem Orlando Fusioso (1532), or quite literally “Orlando’s Frenzy,” by the Italian poet Ludovico Alcina Ariosto. The poem is a compilation of stories about the knights of Charlemagne and their grand adventures during wars with Muslim Spain. Ariosto based his work on the unfinished epic poem Orlando Innamorato (1495) by Matteo Maria Boiardo. Two plot threads connect the stories in the collection; the tale of the knight Orlando’s fall to madness and the star -crossed love of Ruggiero and the woman Bradamante. In Ariosto’s poem, Ruggiero and Bradamante are knights from opposing sides of the war who find love, but Ruggiero is captured and put under a spell by the sorceress Alcina. Handel’s opera focuses on this romantic conflict, emphasizing the love between these characters and their struggle to stay together. Handel used the libretto of the Italian opera L'Isola d'Alcina (1728) by Riccardo Broschi for his own composition. Broschi’s opera is mostly lost, but the libretto lives on with alterations by librettist Antonio Marchi, one of Handel’s frequent collaborators. Handel’s Alcina became part of society’s historical game of telephone, where artists focus on a different plot element and interpretation of the drama in each retelling. For Handel, the emphasis is on the joys and trials of love with various kinds of love represented; Alcina’s possession of Ruggiero is Mania and Morgana’s love for the disguised Bradamante is Eros. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXXII, Number 2 Summer 2017 REFLECTIONS ON THE SOURCES REPORT FROM HALLE AND STAGING OF SEMELE Graydon Beeks Mark Risinger My interest in preparing the forthcoming HHA edition of Semele originated over a couple of summers in the mid-1990s, during the time I spent studying Handel’s autograph and completing research for my dissertation. I had fallen in love with the music some time before, thanks to recordings by John Nelson and others: from the opening bars, the music captures the listener’s imagination and reflects the turbulent nature of the story about to unfold, and I had already been completely drawn in by the succession of beautiful moments Handel creates as Semele ascends to near-immortality Because the Handel Festival in Halle now stretches over and then becomes the victim of her own rashness and folly. three weekends, it is not always possible to schedule the Handel Encountering the manuscript sources firsthand, however, Conference and the various meetings that precede it to coincide opened up a whole new realm of appreciation and affection. As with the opening festivities. This year the meetings took place at happens to most of us, I suspect, when we first confront a Handel the end of the first full week and the Conference at the beginning autograph, the overwhelming thrill of sitting in the presence of so of the second full week. Matters were further complicated by the rare and precious an object meant that it took some time before I fact that the Sunday of the second weekend was Pentecost and the was able to calm down and observe closely enough to accomplish Monday following was a major holiday in Germany.