Kyle Barrett the Dark Knight’S Many Stories Arkham Video Games As Transmedia Pathway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bcsfazine #515

The Newsletter of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association #515 $3.00/Issue Azril la Zine 2016 In This Issue: This and Next Month in BCSFA..........................................0 About BCSFA.......................................................................0 Letters of Comment............................................................1 Calendar...............................................................................8 News-Like Matter..............................................................17 Bedside Manner (Taral Wayne)........................................26 The Mystery of ‘Room 237’ (Michael Bertrand)..............29 Art Credits..........................................................................30 BCSFAzine © April 2016, Volume 44, #4, Issue #515 is the monthly club newsletter published by the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social organiza- tion. ISSN 1490-6406. Please send comments, suggestions, and/or submissions to Felicity Walker (the editor), at felicity4711@ gmail .com or Apartment 601, Manhattan Tower, 6611 Coo- ney Road, Richmond, BC, Canada, V6Y 4C5 (new address). BCSFAzine is distributed monthly at White Dwarf Books, 3715 West 10th Aven- ue, Vancouver, BC, V6R 2G5; telephone 604-228-8223; e-mail whitedwarf@ deadwrite.com. Single copies C$3.00/US$2.00 each. Cheques should be made pay- able to “West Coast Science Fiction Association (WCSFA).” The producers of Wit Gen Stein’s Money would like to remind you that “money” may not mean the same thing to you as it does to other people. This and Next Month in BCSFA Friday 22 April: Submission deadline for May BCSFAzine (ideally). Sunday 17 April at 7 PM: April BCSFA meeting—at Ray Seredin’s, 707 Hamilton Street (recreation room), New Westminster. Friday 29 April: May BCSFAzine production (theoretically). Sunday 15 May at 7 PM: May BCSFA meeting—at Ray Seredin’s. Friday 22 May: Submission deadline for June BCSFAzine (ideally). Friday 27 May: June BCSFAzine production (theoretically). -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

DC/Heroes Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

DC/Heroes Pop! LIst PopVinyls.com Updated April 14, 2018 DC HEROES SERIES 06: Joker Blue Batman Clamshell (SDCC 10) 06: Metallic Joker [CHASE] Blue Metallic Batman Clamshell (SDCC 10) 06: Bobblehead Joker (TARGET) Black Batgirl Clamshell (SDCC 10) 06: Bobblehead Metallic Joker (TARGET) GITD Green Lantern Clamshell (SDCC 10) [CHASE] 01: Batman 06: B&W The Joker (HT) 01: Metallic Batman [CHASE] 06: Black Suit Joker (Walgreens) 01: Blue Retro Batman (SDCC 10) 07: Superman 01: Metallic Blue Retro Batman (SDCC 10) 07: Metallic Superman [CHASE] 01: Error Yellow Symbol Batman 07: Kingdom Come Superman [BEDROCK 01: Error Metallic Yellow Symbol Batman CITY] [CHASE] 07: Bobblehead Superman (TARGET) 01: Flashpoint Batman (NYCC 2011) 07: Bobblehead Metallic Superman 01: Bobblehead Batman (TARGET) (TARGET) [CHASE] 07: B&W Superman (HT) 01: Metallic Bobblehead Batman (TARGET) [CHASE] 07: New 52 Superman (PX) 01: Yellow Rainbow Batman (Ent Earth) 07 Silver Superman LE 144 (HT) 01: Pink Rainbow Batman (Ent Earth) 07 GITD Silhouette Superman (EntEarth) 01: Green Rainbow Batman (Ent Earth) 08: Wonder Woman 01: Orange Rainbow Batman (Ent Earth) 08: Metallic Wonder Woman [CHASE] 01: Blue Rainbow Batman (Ent Earth) 08: B&W Wonder Woman (Toy Tokyo 01: Purple Rainbow Batman (Ent Earth) NYCC EXCLUSIVE) 08: New 52 Wonder Woman (PX) 01: New 52 Batman (PX) 01 Silver Batman LE 108 (HT Employees) 08 GITD Silhouette Wonder Woman (EE) 09: Green Lantern 01 Retro Batman (Ent Earth) 09: Metallic Green Lantern [CHASE] 01 “Michael Keaton” Batman (Gamestop) 09: GITD Green -

Activision Publishing to Showcase Blockbuster Slate of Fan-Favorite Video Games at San Diego Comic-Con 2012

Activision Publishing To Showcase Blockbuster Slate Of Fan-Favorite Video Games At San Diego Comic-Con 2012 Showgoers Will Get Their First Multiplayer Hands-On Opportunity with the Highly Anticipated TRANSFORMERS™: FALL OF CYBERTRON, Celebrate Spidey's Latest Movie Launch with Hands-On Time with The Amazing Spider-Man™, Plus a Surprise Game Reveal During the Marvel Games Panel, Exclusive Game Demos at the Activision Booth, and Much, MUCH More... SANTA MONICA, Calif., July 11, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Gaming, comics, sci-fi, cos-play, and fans from all walks of life the world over will experience a colossal interactive entertainment lineup from Activision Publishing, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI), at San Diego Comic-Con International 2012. Headquartered at booth #5344 in the San Diego Convention Center, Activision is celebrating the theatrical release of the blockbuster hit The Amazing Spider-Man, allowing fans to go beyond the movie and find out what happens next in The Amazing Spider-Man™ video game, plus showcasing some of the most anticipated fan-favorite games in the industry, including TRANSFORMERS™: FALL OF CYBERTRON, 007™ Legends, the all-new The Walking Dead™ video game based on the hit AMC television series, along with a world premiere reveal of a brand new Super Hero video game during the Marvel Games panel on Saturday, July 14th. "We know how passionate our fans are, and San Diego Comic-Con is always a great opportunity for us to showcase our latest video games," said David Oxford, Executive Vice President, Activision Publishing. "These are big, iconic franchises and this is our chance to give back and let the hardest-of-the-hardcore play and experience our video games in a unique and fun setting before they hit stores." Activision's Full San Diego Comic-Con 2012 Booth Activities Include: ● First time multiplayer hands-on with TRANSFORMERS: FALL OF CYBERTRON video game. -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

Schurken Im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel Beschäftigt Sich Mit Den Gegenspielern Der ComicFigur „Batman“

Schurken im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel beschäftigt sich mit den Gegenspielern der Comic-Figur ¹Batmanª. Die einzelnen Figuren werden in alphabetischer Reihenfolge vorgestellt. Dieser Artikel konzentriert sich dabei auf die weniger bekannten Charaktere. Die bekannteren Batman-Antagonisten wie z.B. der Joker oder der Riddler, die als Ikonen der Popkultur Verankerung im kollektiven Gedächtnis gefunden haben, werden in jeweils eigenen Artikeln vorgestellt; in diesem Sammelartikel werden sie nur namentlich gelistet, und durch Links wird auf die jeweiligen Einzelartikel verwiesen. 1 Gegner Batmans im Laufe der Jahrzehnte Die Gesamtheit der (wiederkehrenden) Gegenspieler eines Comic-Helden wird im Fachjargon auch als sogenannte ¹Schurken-Galerieª bezeichnet. Batmans Schurkengalerie gilt gemeinhin als die bekannteste Riege von Antagonisten, die das Medium Comic dem Protagonisten einer Reihe entgegengestellt hat. Auffällig ist dabei zunächst die Vielgestaltigkeit von Batmans Gegenspielern. Unter diesen finden sich die berüchtigten ¹geisteskranken Kriminellenª einerseits, die in erster Linie mit der Figur assoziiert werden, darüber hinaus aber auch zahlreiche ¹konventionelleª Widersacher, die sehr realistisch und daher durchaus glaubhaft sind, wie etwa Straûenschläger, Jugendbanden, Drogenschieber oder Mafiosi. Abseits davon gibt es auch eine Reihe äuûerst unwahrscheinlicher Figuren, wie auûerirdische Welteroberer oder extradimensionale Zauberwesen, die mithin aber selten geworden sind. In den frühesten Batman-Geschichten der 1930er und 1940er Jahre bekam es der Held häufig mit verrückten Wissenschaftlern und Gangstern zu tun, die in ihrem Auftreten und Handeln den Flair der Mobster der Prohibitionszeit atmeten. Frühe wiederkehrende Gegenspieler waren Doctor Death, Professor Hugo Strange und der vampiristische Monk. Die Schurken der 1940er Jahre bilden den harten Kern von Batmans Schurkengalerie: die Figuren dieser Zeit waren vor allem durch die Abenteuer von Dick Tracy inspiriert, der es mit grotesk entstellten Bösewichten zu tun hatte. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

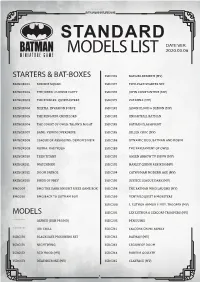

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

Liste Alphabétique Des DVD Du Club Vidéo De La Bibliothèque

Liste alphabétique des DVD du club vidéo de la bibliothèque Merci à nos donateurs : Fonds de développement du collège Édouard-Montpetit (FDCEM) Librairie coopérative Édouard-Montpetit Formation continue – ÉNA Conseil de vie étudiante (CVE) – ÉNA septembre 2013 A 791.4372F251sd 2 fast 2 furious / directed by John Singleton A 791.4372 D487pd 2 Frogs dans l'Ouest [enregistrement vidéo] = 2 Frogs in the West / réalisation, Dany Papineau. A 791.4372 T845hd Les 3 p'tits cochons [enregistrement vidéo] = The 3 little pigs / réalisation, Patrick Huard . A 791.4372 F216asd Les 4 fantastiques et le surfer d'argent [enregistrement vidéo] = Fantastic 4. Rise of the silver surfer / réalisation, Tim Story. A 791.4372 Z587fd 007 Quantum [enregistrement vidéo] = Quantum of solace / réalisation, Marc Forster. A 791.4372 H911od 8 femmes [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, François Ozon. A 791.4372E34hd 8 Mile / directed by Curtis Hanson A 791.4372N714nd 9/11 / directed by James Hanlon, Gédéon Naudet, Jules Naudet A 791.4372 D619pd 10 1/2 [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Daniel Grou (Podz). A 791.4372O59bd 11'09''01-September 11 / produit par Alain Brigand A 791.4372T447wd 13 going on 30 / directed by Gary Winick A 791.4372 Q7fd 15 février 1839 [enregistrement vidéo] / scénario et réalisation, Pierre Falardeau. A 791.4372 S625dd 16 rues [enregistrement vidéo] = 16 blocks / réalisation, Richard Donner. A 791.4372D619sd 18 ans après / scénario et réalisation, Coline Serreau A 791.4372V784ed 20 h 17, rue Darling / scénario et réalisation, Bernard Émond A 791.4372T971gad 21 grams / directed by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu ©Cégep Édouard-Montpetit – Bibliothèque de l’École nationale d'aérotechnique - Mise à jour : 30 septembre 2013 Page 1 A 791.4372 T971Ld 21 Jump Street [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller. -

Batman: the Black Mirror Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BATMAN: THE BLACK MIRROR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott Snyder | 304 pages | 12 Mar 2013 | DC Comics | 9781401232078 | English | United States Batman: The Black Mirror PDF Book It's difficult for books with as much acclaim as The Black Mirror to live up to the hype, and although I wouldn't say it was truly special, I still have plenty of praise to give. That is not to say that this is not a great work in itself. Having said that, Dick is a good Batman. All's I'm saying is that I've been thinking about what the DC reboot really means for all the long-running superheroes it affected last year. The secondary key character for the other half of the issues is Commissioner Jim Gordon. None of the characters were appealing. As if Gotham isn't full of enough darkness and sickness of the soul. One thing he does extremely well here is write colorful villains in the gangster-plus mode of the best Bat-villains, some of whom are familiar The Joker, Man-Bat and Killer Croc variants , but many of whom are new The Dealer of Mirror House, Roadrunner, Tiger Shark , and come up with scenarios to provide his artists with cool, fantastical, somewhat creepy and off imagery For example, the release of an aviary of exotic birds, filling the city scape with huge, strange birds that don't belong there; Tiger Shark, meanwhile, keeps orcas with him, and the body of one murder victim is found in the belly of a dead orca, found in the lobby of a bank. -

Amuse Bouche

CAT-TALES AAMUSE BBOUCHE CAT-TALES AAMUSE BBOUCHE By Chris Dee Edited by David L. COPYRIGHT © 2006 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION AMUSE BOUCHE As hostess for the Iceberg Lounge, Raven made a decent living, but she was still a working girl and vacations were an extravagance. She’d taken the occasional weekend upstate when it turned serious with this guy or that one. And there was a wild bachelorette trip on a train to Savannah with three other bridesmaids before her sister’s wedding. That was really it. She’d never been out of the country before. But the travel agent Oswald sent her to, called Royal Wing Excursions, booked vacation packages for well-traveled Gothamites. Raven said she dreamed of going to Paris, but the City of Lights must have been too familiar to the Royal Wing clients because she only got a day there. Once her plane landed, she got to see the Eiffel Tower, eat in a real French café, and take a cruise down the Seine. Then she had to find her bed & breakfast in Monmarte and, first thing in the morning, catch a special train to a place called Savigny les Beaune where she met up with Florent her guide, her fellow travelers, and a not-too-intimidating bicycle. They set off the next morning for Nuits St. Georges and by the time they arrived at their first vineyard, everyone was on a first name basis. -

Movielistings

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, June 8, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESDAY’S SATURDAY EVENING JUNE 9, 2007 SUNDAY EVENING JUNE 10, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Family (TV14) Family Jewels Family Jewels Family Jewels Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Flip This House: Roach Flip This House: Burning Star Wars: Empire of Dreams The profound effects of Flip This House: Roach 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E House (TV G) (R) Down the House Star Wars. (TVPG) House (TV G) (R) (R) (R) (N) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) F.