NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Vet Intern Med

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pets Corner Dog Show

PETS CORNER ALL ENTRIES TAKEN ON THE DAY. Entry Fee €3. Prizes: 1st €15, 2nd €10, 3rd €5. Judging starts at 12noon. Class 163 - Any Pet (Bring along you favourite Pet, cat,rabbit, hamster,etc.) DOG SHOW ALL ENTRIES TAKEN ON THE DAY. Entry Fee €5. Prizes: 1st €25, 2nd €15, 3rd €10. Only two 1st Prizes May be awarded to any one dog. Judging starts after Pet’s Corner Judging. ALL DOGS MUST BE KEPT ON A LEASH AND FULLY UNDER CONTROL. DOG EXHIBITORS PLEASE NOTE ALL DOGS MUST BE KEPT IN THE AREA WHERE THEY ARE TO BE JUGDED. Class 164 - Dogs Fancy Dress Class 165 - Gundog Group Class 166 - Hound Group. Class 167 - Utility Group. Class 168 - Toy Group. Class 169 - Terrier Group. Class 170 - Working Group. (exc. Gundog & Sheepdog) Class 171 - Pastoral Group. (Collies & Sheepdogs, etc) Class 172 - Best Puppy under 12 months. Class 173 - Junior Handling. (under 13) Class 174 - Ladies Handling. Class 175 - Gents Handling. Class 176 - Dog, with the waggiest tail. Class 177 - Best Groomed Dog. Class 178 - Dog adopted from Rescue Centre. Class 179 - Any variety confined to Ballinrobe parish. Class 180 - Veteran Dog greater than 8 years old. Class 181 - Champion Handler of the Show confined to prizewinners of classes 173-175. Champion €30. Class 182 - Champion Dog of the Show. J Grogan Trophy & €50. Reserve €30. Class 183 Eyrecourt Agricultural Show & Irish Shows Association Present The ALL Ireland Irish Native Breed Championship Rules & Conditions 1. The competition is confined to Irish native breed any variety—dog / bitch which are as follows: (A) Irish Glen of Imaal Terrier (B) Irish Red Setter (C ) Irish Red and White Setter (D) Irish Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier € Irish Terrier (F) Irish Water Spaniel (G) Irish Wolfhound (H) Kerry Beagle (I) Kerry Blue 2. -

British Veterinary Association / Kennel Club Hip Dysplasia Scheme

British Veterinary Association / Kennel Club Hip Dysplasia Scheme Breed Specific Statistics – 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2016 Hip scores should be considered along with other criteria as part of a responsible breeding programme, and it is recommended that breeders choose breeding stock with hip scores around and ideally below the breed median score, depending on the level of HD in the breed. HD status of parents, siblings and progeny for Kennel Club registered dogs should also be considered, and these together with a three generation Health Test Pedigree may be downloaded via the Health Test Results Finder, available on the Kennel Club’s online health tool Mate Select (www.mateselect.org.uk). In addition, estimated breeding values (EBVs) are available for breeds in which a significant number of dogs have been graded, via the same link. For further advice on the interpretation and use of hip scores see www.bva.co.uk/chs The breed median score is the score of the ‘average’ dog in that breed (i.e. an equal number of dogs in that breed have better and worse scores). No. 15 year No. 15 year 5 year 5 year Breed score in Breed score in Range Median Median Range Median Median 15 years 15 years Affenpinscher 40 8 – 90 13 14 Beagle 62 8 - 71 16 17 Afghan Hound 18 0 – 73 8.5 27 Bearded Collie 1511 0 – 70 9 9 Airedale Terrier 933 4 – 72 11 10 Beauceron 42 2 – 23 10 10 Akita 1029 0 – 91 7 7 Belgian Shepherd 249 0 – 37 8 8 Dog (Groenendael) Alaskan Malamute 1248 0 – 78 10 10 Belgian Shepherd 16 5 - 16 10 14 Dog (Laekenois) Anatolian 63 3 – 67 9 -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

MSK Dog EN Letterus.Indd

Most Common Breeds size: S = small; M = medium; L = large; G = giant lifespan: A = approx. 9 years; B = approx. 11 years; C = approx. 15 years hound group gundog group breed size lifespan breed size lifespan Afghan Hound L B Bracco Italiano L B Azawakh L B Brittany M B Basenji M B English Setter L B Basset Bleu de Gascogne M B German Long-Haired Pointer L B Basset Fauve de Bretagne M B German Short-Haired Pointer L B Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) M B German Wire-Haired Pointer L B Basset Griffon Vendeen (Petit) M B Gordon Setter L B Basset Hound M B Hungarian Vizsla L B Bavarian Mountain Hound M B Hungarian Wire-Haired Vizsla L B Beagle M B Irish Red and White Setter L B Bloodhound L A Irish Setter L B Borzoi L B Italian Spinone L B Cirneco dell'Etna M B Kooikerhondje M B Dachshund (Long-Haired) M B Korthals Griffon L B Dachshund (Miniature Long-Haired) S C Lagotto Romagnolo M B Dachshund (Smooth-Haired) M B Large Munsterlander L B Dachshund (Miniature Smooth-Haired) S C Pointer L B Dachshund (Wire-Haired) M B Retriever (Chesapeake Bay) L B Dachshund (Miniature Wire-Haired) S C Retriever (Curly-Coated) L B Deerhound L B Retriever (Flat-Coated) L B Finnish Spitz M B Retriever (Golden) L B Foxhound L B Retriever (Labrador) L B Grand Bleu de Gascogne L B Retriever (Nova Scotia Duck-Tolling) M B Greyhound L B Slovakian Rough-Haired Pointer L B Hamiltonstovare L B Small Munsterlander M B Ibizan Hound L B Spaniel (American Cocker) M B Irish Wolfhound G A Spaniel (Clumber) L B Norwegian Elkhound L B Spaniel (Cocker) M B Otterhound L B Spaniel -

FCI Standard No

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ 02.04.2001/EN _______________________________________________________________ FCI-Standard N° 160 IRISH WOLFHOUND 2 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: Ireland. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE ORIGINAL VALID STANDARD: 13.03.2001. UTILIZATION: Up to the end of the17th century, Irish Wolfhounds were used for hunting wolves and deer in Ireland. They were also used for hunting the wolves that infested large areas of Europe before the forests were cleared. CLASSIFICATIONS FCI: Group 10 Sighthounds. Section 2 Rough-haired Sighthounds. Without working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: We know the continental Celts kept a greyhound probably descended from the greyhound first depicted in Egyptian paintings. Like their continental cousins, the Irish Celts were interested in breeding large hounds. These large Irish hounds could have had smooth or rough coats, but in later times, the rough coat predominated possibly because of the Irish climate. The first written account of these dogs was by a Roman Consul 391 A.D. but they were already established in Ireland in the first century A.D. when Setanta changed his name to Cu-Chulainn (the hound of Culann). Mention is made of the Uisneach (1st century) taking 150 hounds with them in their flight to Scotland. Irish hounds undoubtedly formed the basis of the Scottish Deerhound. Pairs of Irish hounds were prized as gifts by the Royal houses of Europe, Scandinavia and elsewhere from the Middle ages to the 17th century. They were sent to England, Spain, France, Sweden, Denmark, Persia, India and Poland. In the15th century each county in Ireland was required to keep 24 wolfdogs to protect farmers' flocks from the ravages of wolves. -

HOUND GROUP Photos Compliments of A.K.C

HOUND GROUP Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AFGHAN HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AMERICAN ENGLISH COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AMERICAN FOXHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H AZAWAKH HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BASENJI HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BASSET HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BEAGLE HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLACK AND TAN COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLOODHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BLUETICK COONHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H BORZOI HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H CIRNECO DELL’ETNA HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H DACHSHUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H ENGLISH FOXHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H GREYHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H HARRIER HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H IBIZAN HOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H IRISH WOLFHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H NORWEGIAN ELKHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. Wyoming 4-H OTTERHOUND HOUND Photos Compliments of A.K.C. -

The Illustrated Standard of the Irish Wolfhound

THE ILLUSTRATED STANDARD OF THE IRISH WOLFHOUND INTRODUCTION Irish Wolfhounds, according to legend and history, originated in those days long ago veiled in antiquity when bards and story tellers were the caretakers of history and the reporters of current events. One of the earliest recorded references to Irish Wolfhounds is in Roman records dating to 391 A.D. Often given as royal gifts, they hunted with their masters, fought beside them in battle, guarded their castles, played with their children, and laid quietly by the fire as family friends. They were fierce hunters of wolves and deer. Following a severe famine in the 1840s and the arrival of the shot gun that replaced the need for the Irish Wolfdog to control wolves, there were very few Irish Wolfhounds left in Ireland. It was in the mid 19th century that Captain George A. Graham gathered those specimens of the breed he could find and began a breeding program, working for 20 years to re-establish the Breed. The Standard of the Breed written by Captain Graham in 1885 is basically the standard to which we still adhere. Today’s hound seldom hunts live game, does not go to war, and is owned not only by the highly placed but also by the common man. Yet he still has that keen hunting instinct, guards his home and family, is a constant companion and friend, lies by the fire at night, and plays with the kids. Being a family companion has replaced his original, primary function as a hunting hound, but he will still, untrained to do so, give chase to fleeing prey. -

Some Haematological Values of Irish Wolfhounds in Australia

................................................................................................................................ Table 1. Comparison of haematological values (means f SD) of Irish Some haematological values of Wolfhounds and other breeds of dog. Irish Wolfhounds in Australia Present study Sullivan et at6 Value Irish Wolfhounds Greyhounds Non-sighthound P CLARK Department of Veterinary Science, breeds BW PARRY The University of Melbourne. n = 22 n = 36 n = 22 250 Princes Highway, PCV (UL) 0.49 f 0.04' 0.54 f 0.048 0.47 t 0.04A Werribee, Victoria, 3030 Red cell count (xl0'VL) 6.8 f 0.6AB 6.7 f 0.4A 7.1 f 0.48 Haemoglobin (g/L) 17.4f 1.5A 19.9 f 1.€i8 17.5 t 1.31 rish Wolthounds are a breed ofdog originally used to hunt by MCV (fL) 66.8 f 1.EA 81.2 f 8.28 65.6 f 2.gA I chasing quarry. They belong to a group of breeds commonly MCH (pg) 25.5 2 1.OA 3Of3.l8 24.7 f 1 .ZC referred to as sighthounds. Other breeds in this category include MCHC (g/L) 38.3 f 0 6A 37 1 f 1.5A 37.7 f 2.OA the Greyhound, the Afghan Hound, the Saluki, the Whippet Leukocyte count (xlOg/L) 8.4 f 1.51 7.9 f 2.fjA 7.4 f 2.9' and the Scottish Deerhound. Reports of haematological values Bands ("A) 1.3 f 1.1 have been published for the Greyhound'" and for the Afghan Neutrophils (%) 63.3 f 9.4 Hound, the Saluki and the Whippet. -

Guide to Buying an Irish Wolfhound Puppy

Buying an Irish Wolfhound puppy is a long term commitment. It is important to take your time to research thoroughly before making a decision which will affect your life for years to come. This guide will highlight the important aspects to be aware of when you are considering introducing this significant addition into your family. This guide has been put together to help you find your way to a reputable breeder. It is important that you take great care when choosing your breeder. It is the most important decision you will make – much more important than choosing the individual pup. There are a number of websites offering Irish Wolfhounds for sale. Some of them look wonderful and state all the right things. Be careful, things are not always what they appear to be, and behind many of these websites are commercial and volume breeders. Avoid buying from free advert websites such as Gumtree, Preloved or Pets4Homes, or from adverts in local newspapers. Responding to these adverts runs the risk of buying from puppy farms, or falling foul of scams, where you pay your money, but there are no puppies available. Many Irish Wolfhound breeders do not advertise. Responsible breeders breed to maintain their lines and often have a waiting list for their pups. However, as the size of litters is unpredictable, they may sometimes have puppies available. These breeders are very selective about who they will trust with their pups and will often ask a wide range of questions of prospective buyers. The best place to start your search is to contact one of the Breed Clubs. -

Cattle Dogs (Except Swiss Cattle Dogs)

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) Place Albert 1er, 13, B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique), tel : +32.71.59.12.38, fax : +32.71.59.22.29, email : [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________________________ NOMENCLATORUL RASELOR CANINE FCI DENUMIREA RASELOR ESTE REDATĂ ÎN LIMBA ŢĂRII DE ORIGINE. VARIETĂŢILE DE RASĂ SI DENUMIRILE TARILOR DE ORIGINE SAU PATRONAJ SUNT REDATE ÎN LIMBA ENGLEZĂ CONŢINE SPECIFICAŢIILE CU PRIVIRE LA ACORDAREA TITLULUI C.A.C.I.B. DE CĂTRE F.C.I. SI ACORDAREA TITLULUI C.A.C. DE CĂTRE A.CH.R. VALABIL DE LA 01.03.2008 ( ) = Numai pentru ţările care au solicitat ( ) = Numai pentru ţările nordice (Suedia, Norvegia, Finlanda) GRUPA / GROUP 1 Câini de turmă și Câini de cireadă (cu excepția câinilor de cireadă Elvețieni) Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) Section 1: Câini de turmă / Sheepdogs Section 2: Câini de cireadă ( cu excepția câinilor de cireadă Elvețieni) / Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle dogs) CACIB CAC WORKING TRIAL SECTION 1 : SHEEPDOGS 1. AUSTRALIA Australian Kelpie (293) 2. BELGIUM Chien de Berger Belge (15) (Belgian Shepherd Dog) a) Groenendael b) Laekenois c) Malinois d) Tervueren Schipperke (83) 3. CROATIA Hrvatski Ovcar (277) (Croatian Sheepdog) 4. FRANCE Berger de Beauce (Beauceron) (44) Berger de Brie (Briard) (113) Chien de Berger des Pyrénées à poil long (141) (Long-haired Pyrenean Sheepdog) Berger Picard (176) (Picardy Sheepdog) Berger des Pyrénées à face rase (138) (Pyrenean Sheepdog - smooth faced) 5. GERMANY Deutscher Schaferhund (166) German Shepherd Dog a) Double coat b) Long and harsh outer coat 6. GREAT BRITAIN Bearded Collie (271) Old English Sheepdog (Bobtail) (16) Border Collie (297) Collie Rough (156) Collie Smooth (296) Shetland Sheepdog (88) Welsh Corgi Cardigan (38) Welsh Corgi Pembroke (39) 7. -

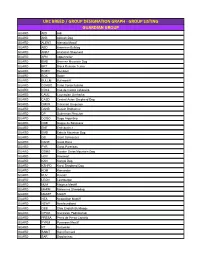

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

Annual Health Report 2020 Hip Scores by Breed

Annual health report 2020 Hip scores by breed Data Calculated to 31/12/20 The following is an annual summary, covering all breeds which have had a least one dog scored, using data from the current approximated breeding population (data from dogs scored in the last 15 years only). By representing dogs scored in the last 15 years, a more accurate reflection of each breed’s current state of health and improvement is given. The 5-year median here refers to dogs scored between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2020. The data reflects Kennel Club registered dogs only. 15 years 5 years Breed Tested 15 years Tested 2020 Mean Min Max Median Mean Median Affenpinscher 40 0 17.9 8.0 90.0 13.0 23.8 23.0 Afghan Hound 90 4 12.0 4.0 73.0 10.0 12.3 10.0 Airedale Terrier 873 35 13.7 4.0 77.0 11.0 13.7 11.0 Akita 805 21 7.6 0.0 70.0 6.0 8.2 7.0 Alaskan Malamute 1174 30 11.6 0.0 78.0 10.0 10.2 9.0 Anatolian Shepherd Dog 32 0 12.8 2.0 46.0 9.0 13.8 12.0 Australian Cattle Dog 115 6 12.4 4.0 56.0 11.0 11.4 11.0 Australian Shepherd Dog 513 26 10.7 0.0 92.0 10.0 11.4 10.0 Barbet 18 4 12.2 2.0 46.0 9.5 13.3 10.5 Basenji 41 2 8.0 0.0 19.0 8.0 7.6 8.0 Basset Fauve De Bretagne 1 0 13.0 13.0 13.0 13.0 13.0 13.0 Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) 5 0 18.4 8.0 37.0 16.0 21.7 20.0 Basset Griffon Vendeen (Petit) 1 0 7.0 7.0 7.0 7.0 Basset Hound 4 0 14.5 5.0 33.0 10.0 5.0 5.0 Bavarian Mountain Hound 75 1 10.6 4.0 29.0 10.0 11.0 10.0 Beagle 56 5 20.8 8.0 71.0 16.5 21.7 18.5 Bearded Collie 1306 22 9.7 0.0 70.0 9.0 9.5 9.0 Beauceron 52 4 10.3 2.0 23.0 10.0 10.1 10.0 Belgian