Horizontal and Vertical Movements of Humpback Whales Inform the Use of Critical Pelagic Habitats in the Western South Pacifc Solène Derville1,2,3,4*, Leigh G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Report Tropical Storm Bud 13 - 17 June 2000

Preliminary Report Tropical Storm Bud 13 - 17 June 2000 Jack Beven National Hurricane Center 21 July 2000 a. Synoptic history The origins of Bud can be traced to a tropical wave that emerged from the coast of Africa on 22 May. The wave generated little convection as it moved across the Atlantic and Caribbean. The wave moved into the eastern Pacific on 6 June, but showed few signs of organization until 11 June when a broad low pressure area formed a few hundred miles southwest of Acapulco, Mexico. The initial Dvorak intensity estimates were made that day. Further development was slow, as the low exhibited multiple centers for much of 11-12 June. As one center emerged as dominant, the system became a tropical depression near 0600 UTC 13 June about 370 n mi south-southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico (Table 1). The depression became Tropical Storm Bud six hours later as it moved northwestward. Bud reached a peak intensity of 45 kt early on 14 June while turning north-northwestward. The peak intensity was maintained for 12 hr, followed by slow weakening due to a combination of increasing vertical shear and cooler sea surface temperatures. Bud passed just northeast of Socorro Island on 15 June as a 40 kt tropical storm. It weakened to a depression on 16 June as it slowed to an erratic drift about 70 n mi north of Socorro Island. Bud dissipated as a tropical cyclone on 17 June about 90 n mi north-northeast of Socorro Island; however, the remnant broad low persisted until 19 June. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds

B BIO VIEW Curator Notes From the Brink of Extinct Rebuilding the Socorro Dove Population by Peter Shannon, Rio Grande Zoo Curator of Birds In terms of conservation efforts, the Rio Grande Zoo is a rare breed in its own right, using its expertise to preserve and breed species whose numbers have dwindled to almost nothing both in the wild and in captivity. Recently, we took charge of a little over one-tenth of the entire world’s population of Socorro doves which have been officially extinct in the wild since 1978 and are now represented by only 100 genetically pure captive individuals that have been carefully preserved in European institutions. Of these 100 unique birds, 13 of them are now here at RGZ, making us the only holding facility in North America for this species and the beginning of this continent’s population for them. After spending a month in quarantine, the birds arrived safe and sound on November 18 from the Edinburgh and Paignton Zoos in England. Other doves have been kept in private aviaries in California, but have been hybridized with the closely related mourning dove, so are not genetically pure. History and Background Socorro doves were once common on Socorro Island, the largest of the four islands making up the Revillagigedo Archipelago in the East- ern Pacific ocean about 430 miles due west of Manzanillo, Mexico and 290 miles south of the tip of Baja, California. Although the doves were first described by 19th century American naturalist Andrew Jackson Grayson, virtually nothing is known about their breeding behavior in the wild. -

Aqua Safari and Living Underwater, Cozumel +

The Private, Exclusive Guide for Serious Divers June 2015 Vol. 30, No. 6 Aqua Safari and Living Underwater, Cozumel Two different dive operators, two different views IN THIS ISSUE: Aqua Safari and Living These days, I get many reader queries about two dive Underwater, Cozumel . 1. destinations in particular -- Raja Ampat and Cozumel. While we periodically cover Raja Ampat, it has been a Your Fellow Divers Need Your while since we’ve written about Cozumel, and because two Reader Reports . 3. of our long-time correspondents were heading there just weeks apart, I decided to run stories with contrasting Dehydration and Diving . 4. views about two different dive operators. I think this can be extremely helpful for divers who have never vis- Could This Diver’s Death Have ited Cozumel, and for those who have, perhaps our writers Been Prevented? . .6 . will offer you new options. Now, go get wet! Little Cayman, Cocos, Palau . 9. -- Ben Davison They Left Without the Dead * * * * * Diver’s Body . 11. Murder of Stuart Cove’s Dock listening for splendid toadfish Manager . 12. Dear Fellow Diver: Rarest Dive Watch Ever? . 13. One of my favorite fish is Cozumel’s endemic splen- Starving Underwater did toadfish, which I look for under low-ceiling recesses Photographers: Part I . 14. on the sand. The vibrant yellow fin borders and gray-, blue- and white-striped body pop out, making its discovery Dive Your Golf Course . 15. a real treat. As a repeat diver with Aqua Safari, I was Bubbles Up . 16. fortunate on this trip to be guided by Mariano, a Yucatan native who has been Bad Night on the Wind Dancer 17 with Aqua Safari for 20 years. -

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico Item Type Article; text Authors Farmer, Jack D.; Farmer, Maria C.; Berger, Rainer Citation Farmer, J. D., Farmer, M. C., & Berger, R. (1993). Radiocarbon ages of lacustrine deposits in volcanic sequences of the Lomas Coloradas area, Socorro Island, Mexico. Radiocarbon, 35(2), 253-262. DOI 10.1017/S0033822200064924 Publisher Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona Journal Radiocarbon Rights Copyright © by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. All rights reserved. Download date 28/09/2021 10:52:25 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/653375 [RADIOCARBON, VOL. 35, No. 2, 1993, P. 253-262] RADIOCARBON AGES OF LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS IN VOLCANIC SEQUENCES OF THE LOMAS COLORADAS AREA, SOCORRO ISLAND, MEXICO JACK D. FARMERI, MARIA C. FARMER2 and RAINER BERGER3 ABSTRACT. Extensive eruptions of alkalic basalt from low-elevation fissures and vents on the southern flank of the dormant volcano, Cerro Evermann, accompanied the most recent phase of volcanic activity on Socorro Island, and created 14C the Lomas Coloradas, a broad, gently sloping terrain comprising the southern part of the island. We obtained ages of 4690 ± 270 BP (5000-5700 cal BP) and 5040 ± 460 BP (5300-6300 cal BP) from lacustrine deposits that occur within volcanic sequences of the lower Lomas Coloradas. Apparently, the sediments accumulated within a topographic depression between two scoria cones shortly after they formed. The lacustrine environment was destroyed when the cones were breached by headward erosion of adjacent stream drainages. -

Parque Nacional Revillagigedo

EVALUATION REPORT Parque Nacional Revillagigedo Location: Revillagigedo Archipelago, Mexico, Eastern Pacific Ocean Blue Park Status: Nominated (2020), Evaluated (2021) MPAtlas.org ID: 68808404 Manager(s): Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) MAPS 2 1. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA 1.1 Biodiversity Value 4 1.2 Implementation 8 2. AWARD STATUS CRITERIA 2.1 Regulations 11 2.2 Design, Management, and Compliance 13 3. SYSTEM PRIORITIES 3.1 Ecosystem Representation 18 3.2 Ecological Spatial Connectivity 18 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: Evidence of MPA Effects 19 Figure 1: Revillagigedo National Park, located 400 km south of Mexico’s Baja peninsula, covers 148,087 km2 and includes 3 zone types – Research (solid blue), Tourism (dotted), and Traditional Use/Naval (lined) – all of which ban all extractive activities. It is partially surrounded by the Deep Mexican Pacific Biosphere Reserve (grey) which protects the water column below 800 m. All 3 zones of the National Park are shown in the same shade of dark blue, reflecting that they all have Regulations Based Classification scores ≤ 3, corresponding with a fully protected status (see Section 2.1 for more information about the regulations associated with these zones). (Source: MPAtlas, Marine Conservation Institute) 2 Figure 2: Three-dimensional map of the Revillagigedo Marine National Park shows the bathymetry around Revillagigedo’s islands. (Source: Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, 2018) 3 1.1 Eligibility Criteria: Biodiversity Value (must satisfy at least one) 1.1.1. Includes rare, unique, or representative ecosystems. The Revillagigedo Archipelago is comprised of a variety of unique ecosystems, due in part to its proximity to the convergence of five tectonic plates. -

Annual Report 2007 AMERICAN BIRD CONSERVANCY from the Chairman and the President

Annual Report 2007 AMERICAN BIRD CONSERVANCY From the Chairman and the President In the Catbird Seat Gray Catbird: Greg Lavaty member recently mentioned that he thought the threats to birds and what is being done to overcome American Bird Conservancy is “in the catbird them. Please have a look at BNN on ABC’s website, seat.” This saying, popularized by the writer, www.abcbirds.org—we guarantee you’ll enjoy it. AJames Thurber, is generally used to mean one is in a high, prominent, and advantageous position, and so we were Your support is fundamental to our success, and it has flattered by the compliment. In nature, though, it is more increased exponentially through your support of ABC’s often the mockingbird that sits high and visible for all to American Birds Campaign, a drive based on measurable see, while the catbird makes a big stir but remains hidden conservation outcomes. We are pleased to report, at deep in the bushes. Maybe this is even truer of ABC— the campaign’s halfway point, that we are well past our always effective but not always seen! expectations in protecting birds and their habitats! Thank you for being on our team! Recently the New York Times Magazine described ABC as “a smaller, feistier group.” We are proud of being small, But despite what we have already achieved with your nimble, and at the same time feisty in the defense of birds help, ABC is just getting started. This year promises to and their habitats, and that’s why we chose neither the be ABC’s best in expanding reserves for rare species. -

Archipiélago De Revillagigedo

LATIN AMERICA / CARIBBEAN ARCHIPIÉLAGO DE REVILLAGIGEDO MEXICO Manta birostris in San Benedicto - © IUCN German Soler Mexico - Archipiélago de Revillagigedo WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION ARCHIPIÉLAGO DE REVILLAGIGEDO (MEXICO) – ID 1510 IUCN RECOMMENDATION TO WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: To inscribe the property under natural criteria. Key paragraphs of Operational Guidelines: Paragraph 77: Nominated property meets World Heritage criteria (vii), (ix) and (x). Paragraph 78: Nominated property meets integrity and protection and management requirements. 1. DOCUMENTATION (2014). Evaluación de la capacidad de carga para buceo en la Reserva de la Biosfera Archipiélago de a) Date nomination received by IUCN: 16 March Revillagigedo. Informe Final para la Direción de la 2015 Reserva de la Biosiera, CONANP. La Paz, B.C.S. 83 pp. Martínez-Gomez, J. E., & Jacobsen, J.K. (2004). b) Additional information officially requested from The conservation status of Townsend's shearwater and provided by the State Party: A progress report Puffinus auricularis auricularis. Biological Conservation was sent to the State Party on 16 December 2015 116(1): 35-47. Spalding, M.D., Fox, H.E., Allen, G.R., following the IUCN World Heritage Panel meeting. The Davidson, N., Ferdaña, Z.A., Finlayson, M., Halpern, letter reported on progress with the evaluation process B.S., Jorge, M.A., Lombana, A., Lourie, S.A., Martin, and sought further information in a number of areas K.D., McManus, E., Molnar, J., Recchia, C.A. & including the State Party’s willingness to extend the Robertson, J. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: marine no-take zone up to 12 nautical miles (nm) a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. -

Octopus Rubescens Berry, 1953 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae), in the Mexican Tropical Pacific

17 4 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 17 (4): 1107–1112 https://doi.org/10.15560/17.4.1107 Red Octopus, Octopus rubescens Berry, 1953 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae), in the Mexican tropical Pacific María del Carmen Alejo-Plata1, Miguel A. Del Río-Portilla2, Oscar Illescas-Espinosa3, Omar Valencia-Méndez4 1 Instituto de Recursos, Universidad del Mar, Campus Puerto Ángel, Ciudad Universitaria, Puerto Ángel 70902, Oaxaca, México • plata@angel. umar.mx https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-0705 2 Departamento de Acuicultura, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), B.C., Carretera Ensenada- Tijuana No. 3918, Zona Playitas, C.P. 22860, Ensenada, Baja California, México • [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5564- 6023 3 Posgrado en Ecología Marina, Universidad del Mar Campus Puerto Ángel, Oaxaca, México • [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000- 0003-1533-8453 4 Departamento El Hombre y su Ambiente, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Xochimilco, Calzada del Hueso 1100, 04960 Coyoacán, Cuida de México, México • [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8623-5446 * Corresponding author Abstract “Octopus” rubescens Berry, 1953 is an octopus of temperate waters of the western coast of North America. This paper presents the first record of “O.” rubescens from the tropical Mexican Pacific. Twelve octopuses were studied; 10 were collected in tide pools from five localities and two mature males were caught by fishermen in Oaxaca. We used mor- phometric characters and anatomical features of the digestive tract to identify the species. The five localities along the Mexican Pacific coast provide solid evidence that populations of this species have become established in tropical waters. -

EDUCATOR GUIDE EDUCATOR GUIDE Humpback Fun Facts

Macgillivray Freeman’s presented by pacific life EDUCATOR GUIDE EDUCATOR GUIDE Humpback fun Facts WEIGHT At birth: 1 ton LENGTH Adult: 25 - 50 tons Up to 55 feet, with females larger DIET than males; newborns are Krill, about 15 feet long small fish APPEARANCE LIFESPAN Gray or black, with white markings 50 to 90 years on their undersides THREATS Entanglement in fishing gear, ship strikes, habitat impacts 4 EDUCATOR GUIDE The Humpback Whales Educator Guide, created by MacGillivray Freeman Films Educational Foundation in partnership with MacGillivray Freeman Films and Orange County Community Foundation, is appropriate for all intermediate grades (3 to 8) and most useful when used as a companion to the film, but also valuable as a resource on its own. Teachers are strongly encouraged to adapt activities included in this guide to meet the specific needs of the grades they teach and their students. Activities developed for this guide support Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), Ocean Literacy Principles, National Geography Standards and Common Core Language Arts (see page 27 for a standards alignment chart). An extraordinary journey into the mysterious world of one of nature’s most awe-inspiring marine mammals, Humpback Whales takes audiences to Alaska, Hawaii and the remote islands of Tonga for an immersive look at how these whales communicate, sing, feed, play and take care of their young. Captured for the first time with IMAX® 3D cameras, and found in every ocean on earth, humpbacks were nearly driven to extinction 50 years ago, but today are making a steady recovery. Join a team of researchers as they unlock the secrets of the humpback and find out what makes humpbacks the most acrobatic of all whales, why they sing their haunting songs, and why these 55-foot, 50-ton animals migrate up to 10,000 miles round-trip every year. -

EP072016 Frank.Pdf

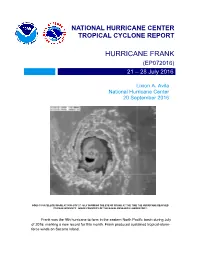

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE FRANK (EP072016) 21 – 28 July 2016 Lixion A. Avila National Hurricane Center 20 September 2016 GOES 15 SATELLITE IMAGE AT 0000 UTC 27 JULY SHOWING THE EYE OF FRANK AT THE TIME THE HURRICANE REACHED ITS PEAK INTENSITY. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE NAVAL RESEARCH LABORATORY. Frank was the fifth hurricane to form in the eastern North Pacific basin during July of 2016, marking a new record for this month. Frank produced sustained tropical-storm- force winds on Socorro Island. Hurricane Frank 2 Hurricane Frank 21 – 28 JULY 2016 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Frank’s origin was associated with a large-amplitude tropical wave that moved off of the west coast of Africa on 10 July. The wave travelled westward across the tropical Atlantic with little thunderstorm activity, and reached the western Caribbean Sea on 18 July. On 19 July, upper-air data from Central America showed that the wave had a well-defined mid-level circulation while the convection was increasing. The wave continued westward and its associated cloudiness and thunderstorms gradually became better organized on 20 July just south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. The formation of a tropical depression occurred at 0600 UTC 21 July about 250 n mi south of Manzanillo, Mexico. The “best track” chart of the tropical cyclone’s path is given in Fig. 1, with the wind and pressure histories shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The best track positions and intensities are listed in Table 11. The cloud pattern continued to become better organized, and by 1200 UTC 21 July, the system was a tropical storm. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 457:221

Vol. 457: 221–240, 2012 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published June 21 doi: 10.3354/meps09857 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Contribution to the Theme Section: ‘Tagging through the stages: ontogeny in biologging’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Ontogeny in marine tagging and tracking science: technologies and data gaps Elliott L. Hazen1,2,*, Sara M. Maxwell3, Helen Bailey4, Steven J. Bograd2, Mark Hamann5, Philippe Gaspar6, Brendan J. Godley7, George L. Shillinger8,9 1University of Hawaii Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 2NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Environmental Research Division, Pacific Grove, California 93950, USA 3Marine Conservation Institute, Bellevue, Washington 98004, USA 4Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Solomons, Maryland 20688, USA 5School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia 6Collecte Localisation Satellites, Parc Technologique du Canal, 31520 Ramonville Saint-Agne, France 7Department of Biosciences, University of Exeter, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9EZ, UK 8Tag-A-Giant Fund − The Ocean Foundation, PO Box 52074, Pacific Grove, California 93950, USA 9Center for Ocean Solutions, Stanford University, 99 Pacific Street, Suite 155A, Monterey, California 93940, USA ABSTRACT: The field of marine tagging and tracking has grown rapidly in recent years as tag sizes have decreased and the diversity of sensors has increased. Tag data provide a unique view on individual movement patterns, at different scales than shipboard surveys, and have been used to discover new habitat areas, characterize oceanographic features, and delineate stock struc- tures, among other purposes. Due to the necessity for small tag-to-body size ratio, tags have largely been deployed on adult animals, resulting in a relative paucity of data on earlier life his- tory stages.