Katherine Bradford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KATHERINE BRADFORD B

KATHERINE BRADFORD b. 1942, New York, NY Lives New York City and works in Brooklyn, NY Education MFA, State University of New York, Purchase, NY BA, Bryn Mawr ColleGe, PA SOLO AND TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2018 Superman Returns With Swimmers, Galerie Haverkampf, Berlin, Germany Friends and StranGers, CANADA, New York, NY MaGenta NiGhts, Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR BeinG like Water, with Jen DeNike, Anat EGbi, Los AnGeles, CA 2017 Superman Responds, Galerie Haverkampf, Berlin, Germany Focus: Katherine Bradford, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, TX Katherine Bradford, Galleria Monica De Cardenas, Milan, Italy Sperone Westwater, New York, NY 2016 Fear of Waves, CANADA, New York, NY Divers and Dreamers, Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR 2015 Fred Giampietro Gallery, New Haven, CT Caldbeck Gallery, Rockland, ME 2014 Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR Arts & Leisure, New York, NY Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 2013 Bowdoin ColleGe Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME Steven Harvey Fine Art, New York, NY 2012 Edward Thorp Gallery, New York, NY John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY 2011 Aucocisco Galleries, Portland ME 2010 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY Samson Projects, Boston, MA 2008 University of Maine Museum, BanGor, ME Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH 2007 Edward Thorp Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Sarah Bowen Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2004 ICON Contemporary Art, Brunswick, ME 2002 Canaday Gallery, Bryn Mawr ColleGe, Bryn Mawr, PA 1996 Katherine Bradford and Mark Wethli, Farnsworth Museum, Rockland, ME 1994 David -

Katherine Bradford

Katherine Bradford Education MFA, State University of New York, Purchase, NY BA, Bryn Mawr College, PA Solo and Two Person Exhibitions 2020 Circus, Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR 2019 Stripes and Legs, Campoli Presti, London, UK Artists, Cops and Circus People, Campoli Presti, Paris France 2018 Superman Returns With Swimmers, Galerie Haverkampf, Berlin, GER Friends and Strangers, CANADA, New York, NY Magenta Nights, Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR Being like Water, with Jen DeNike, Anat Egbi, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Superman Responds, Galerie Haverkampf, Berlin, GER Focus: Katherine Bradford, The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, TX Katherine Bradford, Galleria Monica De Cardenas, Milan, ITL Sperone Westwater, New York, NY 2016 Fear of Waves, CANADA, New York, NY Divers and Dreamers, Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR 2015 Fred Giampietro Gallery, New Haven, CT Caldbeck Gallery, Rockland, ME 2014 Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR Arts & Leisure, New York, NY Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 2013 Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME Steven Harvey Fine Art, New York, NY 2012 Edward Thorp Gallery, New York, NY John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY 2011 Aucocisco Galleries, Portland ME 2010 John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY Samson Projects, Boston, MA 2008 University of Maine Museum, Bangor, ME Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH 2007 Edward Thorp Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Sarah Bowen Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2004 ICON Contemporary Art, Brunswick, ME 2002 Canaday Gallery, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA 1996 Katherine Bradford and Mark Wethli, Farnsworth Museum, Rockland, ME 1994 David Beitzel Gallery, New York, NY 1993 Bernard Toale Gallery, Boston, MA 1992 Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, IL 1991 Victoria Munroe Gallery, New York, NY Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Group Exhibitions 2020 (forthcoming) Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge Mass (forthcoming) A Wild Note of Longing: Albert Pinkham Ryder and a Century of American Art, New Bedford Museum, New Bedford, MA. -

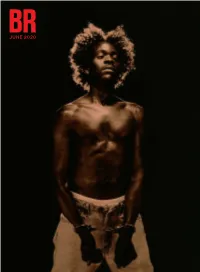

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

Shane Lutzk (American, B

Shane Lutzk (American, b. 1992) Large Black and White Vessel, 2019 Stoneware Collection Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, 2019.13 Acquired with funds provided by the Barton P. and Mary D. Cohen Art Acquisition Endowment of the JCCC Foundation Shane Lutzk develops his monumental ceramic vessels by integrating the precision and structural components found in diverse architecture. While traveling abroad, he was greatly influenced by the historical buildings in Kecskemet, Hungary. His sculptures create a spatial connection with the viewer in large works like Blue Dripped Vessel because of the undulating forms and anthropomorphic scale. In addition to the towering symmetrical sculptures that demonstrate the artist's wheel throwing capabilities, Lutzk builds wall installations and free-standing amorphous sculpture, and these smaller objects are also wheel thrown at first - they are created with cross sections of thrown clay. Whether they retain the wheel's geometry or they take on an elastic undulatin g character through manipulation, Lutzk's clay works convey a personal message: at the age of nine, Lutzk was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes, and much of his work depicts his struggle with this disease. He wants to bring both the ramifications and the positive outcomes that come from diabetes to the public's attention. In this work, the blue concentric circles signify the international symbol for diabetes awareness. Lutzk earned his MFA at Arizona State University in 2017 and his BFA in ceramics at the Kansas City Art Institute in 2014. Kent Monkman (Canadian First Nations, Cree, b. 1965) Sepia Study for The Deposition, 2014 Watercolor and gouache on paper Collection Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017 Kent Monkman’s glamorous, gender-fluid alter-ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, appears in much of his work, including in this study for his painting The Deposition. -

THE D.A.P. CATALOG Spring 2019 LATAM

LATAM THE D.A.P. CATALOG SPRING 2019 artbook.com I Phyllis Galembo: Mexico, Masks & Rituals Text by Víctor M. Espinosa, George Otis. Since 1985, photographer Phyllis Galembo has traveled extensively to photograph sites of ritual dress in Africa and the Caribbean. In her latest body of work, collected in this new publication, Galembo turns to Mexico, where she captures cultural performances with a subterranean political edge. Using a direct, unaffected portrait style, Galembo captures her subjects informally posed but often strikingly attired in traditional or ritualistic dress. Masking is a complex tradition in which the participants transcend the physical world and enter the spiritual realm. Masks, costumes and body paint transform the human body and encode a rich range of political, artistic, theatrical, social and religious meanings on the body. In her vibrant color photographs, Galembo highlights the artistry of the performers, how they use materials from their immediate environment to morph into a fantastical representation of themselves and an idealized vision of a mythical figure. In a gorgeous, fascinating photographic survey of Mexico’s masking practices, Galembo captures her subjects suspended between past, present and future, with their religious, political and cultural affiliations—their personal and collective identifications—displayed on their bodies. Photographer Phyllis Galembo (born 1952) received her MFA from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1977, and was Professor in the Fine Arts Department of SUNY Albany from 1978 to 2018. A 2014 Guggenheim Fellow, Galembo has photographs in numerous public and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Public Library. -

Educational Guide

Educational Guide NOT FOR RESALE Walnut Creek | California | bedfordgallery.org Table of Contents Curator’s Statement…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………..……….1 Artist Statements Mike Alcantara…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….3 Katherine Bradford……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………3 Robert Burden……..………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………4 Enrique Chagoya….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………5 Sandra Chevrier…..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………5 Bill Concannon…….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Marcos D’Alfonso..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……7 Andreas Englund……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………7 Jeremy Fisher……..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Justin Hager………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………8 Cheong-ah Hwang…………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………..……9 Ole Marius Joergensen……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…9 Graham Kirk……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……10 Dave Laro…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………..………10 Adam Lister………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….11 Jannis Markopoulos…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….11 Foto Marvellini…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….12 Simon Monk……..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………12 Mark Newport………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….….13 Aaron Noble…….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….……14 -

![THE D.A.P. CATALOG MID-SUMMER 2019 Pipilotti Rist, Die Geduld [The Patience], 2016](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2519/the-d-a-p-catalog-mid-summer-2019-pipilotti-rist-die-geduld-the-patience-2016-8082519.webp)

THE D.A.P. CATALOG MID-SUMMER 2019 Pipilotti Rist, Die Geduld [The Patience], 2016

THE D.A.P. CATALOG MID-SUMMER 2019 Pipilotti Rist, Die Geduld [The Patience], 2016. Installation view from Kunsthaus Zürich. Photo: Lena Huber. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine. From Pipilotti Rist: Open My Glade, published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See page 20. Mid-Summer 2019 New Releases 2 CATALOG EDITOR Back in Stock 9 Thomas Evans DESIGNER Lower-Priced Books 10 Martha Ormiston PHOTOGRAPHY Books for Summer 12 Justin Lubliner, Carter Seddon COPY WRITING More New Books 14 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia, Arthur Cañedo, Jack Patterson Recently Published by Steidl 26 FRONT COVER IMAGE Stefan Draschan. from Coincidences at Museums, published by Hatje Cantz. See page 5. SPRING/SUMMER ■ 2019 SPRING/SUMMER ■ 2019 Basquiat's "Defacement": The Untold Story Text by Chaédria LaBouvier, Nancy Spector, J. Faith Almiron. Police brutality, racism, graffiti and Jean-Michel Basquiat painted Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) on the wall of Keith the art world of the early-1980s Haring’s studio in 1983 to commemorate the death of a young black artist, who died from injuries sustained while in police custody after being arrested for allegedly tagging a New York City subway Lower East Side converge in one station. Defacement is the starting point for the present volume, which focuses on Basquiat’s response to anti-black racism and police brutality. Basquiat’s “Defacement” explores this chapter painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat in the artist’s career through both the lens of his identity and the Lower East Side as a nexus of activism in the early 1980s, an era marked by the rise of the art market, the AIDS crisis and ongoing racial tensions in the city. -

Graciela Iturbide Merlin James Imi Knoebel Susan Bee Craig Kalpakjian Norma Cole

APRIL 2020 GRACIELA ITURBIDE MERLIN JAMES IMI KNOEBEL SUSAN BEE CRAIG KALPAKJIAN NORMA COLE APRIL 2020 GRACIELA ITURBIDE CRAIG KALPAKJIAN MERLIN JAMES SUSAN BEE IMI KNOEBEL GUEST CRITIC NORMA COLE CARL ANDRE JULIAN LETHBRIDGE TAUBA AUERBACH SOL LEWITT JENNIFER BARTLETT CHRISTIAN MARCLAY BERND AND HILLA BECHER JUSTIN MATHERLY CÉLESTE BOURSIER-MOUGENOT PETER MOORE CECILY BROWN DAVID NOVROS CLAES OLDENBURG & SOPHIE CALLE COOSJE VAN BRUGGEN BEATRICE CARACCIOLO PAUL PFEIFFER SARAH CHARLESWORTH WALID RAAD BRUCE CONNER VERONICA RYAN MARK DI SUVERO JOEL SHAPIRO SAM DURANT RUDOLF STINGEL MATIAS FALDBAKKEN KELLEY WALKER JA'TOVIA GARY DAN WALSH LIZ GLYNN MEG WEBSTER ROBERT GROSVENOR ROBERT WILSON HANS HAACKE JACKIE WINSOR DOUGLAS HUEBLER CAREY YOUNG MICHAEL HURSON BING WRIGHT PAULA COOPER GALLERY 524 W 26TH STREET / 521 W 21ST STREET NEW YORK 212 255 1105 WWW.PAULACOOPERGALLERY.COM Yi Yunyi A Son Older Than His Father April 30 – June 6, 2020 DOOSAN Gallery New York The Deborah Buck Foundation in partnership with the Brooklyn Rail proudly announces the first annual Stepping Up to the Plate Award to: THE BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART for their 2020 Vision initiative to provide greater recognition for female-identifying artists and leaders The award will be given annually to an institution that is working at the forefront of reversing the marginalization of women in the arts About 2020 Vision at The Baltimore Museum of Art “The BMA’s 2020 Vision initiative serves 2020 Vision is a year of exhibitions and programs dedicated to the presentation of to recognize the voices, narratives, the achievements of female identifying artists. The initiative encompasses 16 solo exhibitions and creative innovations of a range of and seven thematic shows. -

Katherine Bradford

Katherine Bradford Richard Levy Gallery [email protected] 505.766.9888 www.levygallery.com @levygallery Katherine Bradford, Storm Tossed Liner, 2013, oil and acrylic on canvas, 21 x 24 inches/ 53.3 x 61 cm: canvas, 22.5 x 25.5/ 57.2 x 64.8 cm: frame, $19,500 Selected Awards 2012 Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant 2011 Guggenheim Fellowship 2005 American Academy of Arts and Letters 2000 Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant Award Selected Solo Exhibitions 2018 Galerie Haverkampf, Berlin, Germany CANADA, New York, NY When I’m actively painting, I try to get in a kind of zone where Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR my rational brain doesn’t take over. 2017 Galerie Haverkampf, Berlin, Germany Katherine Bradford (b. 1942) is an intuitive painter and Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX object maker, best known for her luminous, tactile paintings of Sperone Westwater, New York, NY ships, swimmers, superheros, and divers. Her paintings hover Monica De Cardenas, Milano, ITL in the realm between the real and the imagined. She 2016 CANADA, New York, NY subversively imitates abstract art, reinterpreting it in her own Adams and Ollman, Portland, OR figurative idiom. 2015 Fred Giampietro Gallery, New Haven, CT 2014 Freight & Volume, New York, NY Bradford’s work has received favorable reviews from many Adams & Ollman, Portland, OR publications including the New York Times, Artforum, Art in Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, Tuscaloosa, AL America, and Hyperallergic. She was recently named in the 2013 Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME Huffington Post’s 15 Artists to Watch in 2015 and she is the Steven Harvey Fine Art, New York, NY recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, a 2012 Edward Thorp Gallery, New York, NY Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Pollock-Krasner Foundation John Davis Gallery, Hudson, NY Grant Award. -

Katherine Bradford and Sarah Gamble Adams and Ollman November 7–December 20, 2014 Opening Reception: Friday, November 7 from 6–8Pm

KATHERINE BRADFORD AND SARAH GAMBLE ADAMS AND OLLMAN NOVEMBER 7–DECEMBER 20, 2014 OPENING RECEPTION: FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7 FROM 6–8PM October 1, 2014, Portland, Oregon: Adams and Ollman is pleased to announce a two person exhibition with Katherine Bradford and Sarah Gamble on view November 7 through December 20, 2014. Bradford and Gamble make emotive and exuberant paintings that feature direct, immediate markmaking and brilliant color. Sharing an overlapping visual lexicon, both artists embrace an animistic and raw dream world. On view will be a selection of intimate paintings by Katherine Bradford, whose cast of characters–ships, swimmers, superheroes–are caught midmotion, floating, flying and drifting against bold brush strokes and luminous fields of color. Bradford conjures her symbolic imagery including red skies and archetypal figures from an economy of intuitive and primitive marks. Her lush, painterly surfaces merge abstraction with figuration in a highly personal way to describe, not form, but feeling. The paintings, all nightscapes, flicker and glow with a strange phosphorescent light that suggests deep, dark dreams and a hazy space between reality and imagination. In Red Reflection, a red rectangle becomes a bulky ocean liner adrift and alone in the blackness. In another work, a soaring superman is seen against a starry sky with loopy brush marks trailing behind that suggest that our hero is not on a mission, but on a joy ride. Consistent throughout the work is the suggestion of new frontiers and failed journeys. Humanistic and intense, Bradford's paintings explore the infinite through color, shape, and symbol and are, in turns, humorous, epic, emotional and vulnerable. -

Fourth Anniversary • Allan D'arcangelo • Marcus Rees Roberts

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas May – June 2015 Volume 5, Number 1 Fourth Anniversary • Allan D’Arcangelo • Marcus Rees Roberts • Jane Hyslop • Equestrian Prints of Wenceslaus Hollar In Memory of Michael Miller • Lucy Skaer • In Print / Imprint in the Bronx • Prix de Print • Directory 2015 • News MARLONMARLONMARLON WOBST WOBSTWOBST TGIFTGIF TGIF fromfrom a series a series of fourof four new new lithographs lithographs keystonekeystone editions editionsfinefine art printmakingart printmaking from a series of four new lithographs berlin,keystoneberlin, germany germany +49 editions +49(0)30 (0)30 8561 8561 2736 2736fine art printmaking Edition:Edition: 20 20 [email protected],[email protected] germany +49 (0)30 www.keystone-editions.net 8561 www.keystone-editions.net 2736 6-run6-run lithographs, lithographs, 17.75” 17.75”Edition: x 13” x 13”20 [email protected] www.keystone-editions.net 6-run lithographs, 17.75” x 13” May – June 2015 In This Issue Volume 5, Number 1 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Random Houses Associate Publisher Linda Konheim Kramer 3 Julie Bernatz The Prints of Allan D’Arcangelo Managing Editor Ben Thomas 7 Dana Johnson The Early Prints of Marcus Rees Roberts News Editor Isabella Kendrick Ruth Pelzer-Montada 12 Knowing One’s Place: Manuscript Editor Jane Hyslop’s Entangled Gardens Prudence Crowther Simon Turner 17 Online Columnist The Equestrian Portrait Prints Sarah Kirk Hanley of Wenceslaus Hollar Design Director Lenore Metrick-Chen 23 Skip Langer The Third Way: An Interview with Michael Miller Editor-at-Large Catherine Bindman Prix de Print, No.