Luca Von Felten Final Report from Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 27, 2005 for Immediate Release New City Residence Investment

July 27, 2005 For Immediate Release New City Residence Investment Corporation 1-10-6 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo Tetsuya Fujita, Executive Officer (Securities Code: 8965) Inquiries: CBRE Residential Management K.K. Yoetsu Takizawa, General Manager Planning & Administration TEL: +81-3-6229-3860 Notice Concerning the Proposed Acquisition of Investment Asset New City Residence Investment Corporation (“NCRI” or “the Investment Corporation”) today announced its plan to acquire the following investment asset. 1. Acquisition Details (1) Trust Beneficiary Interest in Real Estate Property Trust Asset (Millions of yen) Projected Acquisition Price Property Name (Note 1) 1 New City Residence Shinjyuku Gyoen I 3,140 2 New City Residence Sasazuka 3,050 3 New City Residence Takanawadai 1,180 4 New City Residence Nihonbashi Ningyocho IV 842 5 New City Residence Shinjyuku Gyoen II 580 6 New City Residence Ginza East IV 510 7 New City Residence Jiyugaoka 1,470 8 New City Residence Mejiro East 1,080 9 New City Residence Iriya 675 10 Park Terrace Ichikawa 620 11 Park Terrace Shioyaki 310 12 Park Terrace Horie 193 Total 13,650 Notes: 1. The projected acquisition price is exclusive of property tax, urban planning tax, consumption tax, and local consumption tax. Figures less than million yen are rounded. 2. The current names of properties 1 through 9 identified in the table above are Duo Scala Shinjuku Gyoen, Duo Scala Sasazuka II, Duo Scala Takanawadai, Dynafort Nihonbashi II, Park Terrace Shinjuku, Duo Scala Irifune, Duo Scala Jiyugaoka, Land Stage Mejiro, and Iriya Amflat III, respectively. The Investment Corporation intends to change the names of each building to those identified in the above table shortly after acquisition. -

WID Hanakoganei 2 WID Shimoigusa WID Tokorozawa

【 Waseda University Waseda University Student Dormitories Affiliated Dormitories】 Waseda University Operated by Kyoritsu Maintenance Co., Ltd. International Dormitories (WID) Waseda Toyama Nishi-Waseda Tokorozawa WID Built in 2008 & Large Public Bath! To HonkawagoeSeibu Shinjuku Line Tokorozawa Campus Lions Viale Hanakoganei 02 Becanse of the various held in our dormitory, our Mitsubishi Electric Tokyo Metro Building Techno Service Rezon Houmei Kodaira City Office, East Area Branch Time required to Takadanobaba Education Center Tamako Cycling Road SEIYU WID Tokorozawa Fukutoshin Line Hanakoganei 2 residents interact a great deal. Circle K (Recreation trail) Post Office 00 Miyagiya Nishi- WID Hanakoganei 2 HanakoganeiNorth Exit Sta. Police box Tokorozawa Kotake- Time required to Kotesashi Three-f 00 RA, Mr. N Higashi-Takano Road Sumitomo Mitsui Tokorozawa Nerima Mukaihara South Exit Banking Corporation Seibu Ikebukuro Line Kodaira-Daisan Nakajimaya Iyoya ※Estimated Time Junior High School Food shop Harada Seibu-dori 40 39 33 Musashikoganei To Anshin Insurance Clinic Service Seven-Eleven 0 2 5 Male Fresh Vegetable shop Jonathan’s SoftBank shop Kotesashi Curtain Park Aoyama Air-conditioner WID Hanakoganei WID Nishi- Higashi-Fushimi Campus Clothing Store Tokorozawa JR Yamanote Line Ikebukuro Higashi- 29 Desk WID Tanashi Chair ■ Murayama 10 Overview WID Tanashi 2 Bed Location/7-2-14 Hanakoganei, Kodaira City, Tokyo 187-0004 Book shelf Hanakoganei Shimoigusa Mejiro Nishi-Waseda Campus Transportation/12-min. walk from Hanakoganei Station on Seibu -

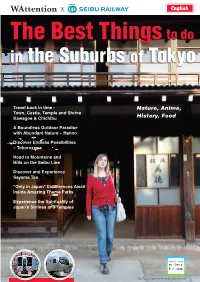

In the Suburbs of Tokyo

English The Best Things to do in the Suburbs of Tokyo Travel back in time - Nature, Anime, Town, Castle, Temple and Shrine Kawagoe & Chichibu History, Food A Boundless Outdoor Paradise with Abundant Nature -- Hanno Discover Endless Possibilities -- Tokorozawa Head to Mountains and Hills on the Seibu Line Discover and Experience Sayama Tea "Only in Japan" Experiences Await Inside Amazing Theme Parks Experience the Spirituality of Japan’s Shrines and Temples Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum SEIBU_EN_2020.indd 1 2020/12/03 11:07 Get around the Seibu Line with the All-you-can-ride Pass With the SEIBU 1Day Pass and other discount tickets, issued by Seibu Railway, you can hop on and off the SEIBU Line as often as you want to experience rich Japanese culture and visit sightseeing gems hidden in the suburbs. The Seibu Lines connect directly to the sacred and traditional places of Kawagoe and Chichibu, where you can enjoy the charm of the Edo period to the fullest. These tickets are the best partner for foreign tourists visiting Japan! Ticket Information Price and Type MOOMINVALLEY PARK Ticket & Travel Pass 3,700 yen SEIBU SEIBU * Only valid for the boarding date. Includes a SEIBU 1Day Pass, 1Day Pass 1Day Pass + Nagatoro ZKLFKDOORZVXQOLPLWHGULGHVRQDOO6(Ζ%85DLOZD\OLQHV H[FHSW 1,000 yen 1,500 yen IRUWKH7DPDJDZD/LQH DEXVWLFNHWWRPHWV¦IURP+DQQď 6WDWLRQRU+LJDVKL+DQQď6WDWLRQDQGDSDUNDGPLVVLRQWLFNHW * Some attractions in the park are charged separately. * SEIBU 2Day Pass and SEIBU 2Day Pass + Nagatoro tickets are also available. * Tickets are only valid on the day of use. Valid on the SEIBU KAWAGOE PASS Seibu Line or the Seibu Line + Chichibu Railway Line 700 yen within the stated area including free use between 1RJDPL6WDWLRQDQG0LWVXPLQHJXFKL6WDWLRQb 7LFNHWV * Tickets are valid for only one day of use for are not valid for the Tamagawa Line) arrival or departure from Seibu-Shinjuku Station, * Additional limited express charge is required. -

Confirmation Notice/ 6 July 2019/ Tokyo-Takadanobaba Thank You So Much for Your Registration for IELTS Test

Confirmation Notice/ 6 July 2019/ Tokyo-Takadanobaba Thank you so much for your registration for IELTS test. This is to inform you of the details for IELTS test. You will receive the speaking confirmation notice via e-mail by 2 days before the test. You can also confirm your speaking test time on Booking Summary Page of your account after receiving the e-mail. Please do not forget to bring your valid passport on the test day. (Please also refer to the information below.) (Written Tests) (Speaking Test) Your venue (1 or 2) will be informed by e-mail. ◆ Test Date: 6 July 2019 (AM) ◆ Test Date: 6 July 2019 (PM) ◆ Venue: Tokyo Fuji University, Main Building 1F (3-8-1 ◆ Venue 1: Japan Study Abroad Foundation 3F (Taiju Takadanobaba, Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 169-0075 Japan) Seimei Bldg. 3F, 1-4-15, Takadanobaba, Shinjuku-ku ◆ Access: From Takadanobaba Station (JR Line, Seibu Shinjuku Tokyo 169-0075 Japan) Line, Tokyo Metro Tozai Line): About 5minute walk/ From Shimo ◆ Access: From JR/Seibu Takadanobaba Station: About 6 Ochiai Station (Seibu Shinjuku Line): About 5minute walk minute walk/ From Tokyo Metro Tozai Line Takadanobaba http://www.fuji.ac.jp/access/ Station: About 3 minute walk/ From Tokyo Metro http://www.fuji.ac.jp/guidance/facility/ (Campus Map) Fukutoshin-line Nishi-Waseda Station : About 4 minute ◆ Arrival Time: 8:30am walk ◆ ID Check: 8:30am-8:55am http://www.japanstudyabroad.org/?page_id=6636 ◆ Test Start: 9:00am ◆ Venue 2: Tokyo Fuji University, Main Building 5F (3-8-1 ◆ Test Finish: 12:20pm (approx.) Takadanobaba, Shinjuku-ku Tokyo 169-007 Japan) ※Same place as where Written parts will be taken place. -

Shinjuku Rules of Play

Shinjuku Rules of Play Gary Kacmarcik Version 2 r8 Tokyo is a city of trains and Shinjuku is the busiest In Shinjuku, you manage one of these con- train station in the world. glomerates. You need to build Stores for the Customers to visit while also constructing the rail Unlike most passenger rail systems, Tokyo has lines to get them there. dozens of companies that run competing rail lines rather than having a single entity that manages rail Every turn, new Customers arrive looking to for the entire city. Many of these companies are purchase a specific good. If you have a path to a large conglomerates that own not only the rail, but Store that sells the goods they want, then you also the major Department Stores at the rail might be able to move those new Customers to stations. your Store and work toward acquiring the most diverse collection of Customers. Shinjuku station (in Shinjuku Ward) expands down into Yoyogi station in Shibuya Ward. A direct rail connection exists between these 2 stations that can be used by any player. Only Stores opened in stations with this Sakura icon may be upgraded to a Department Store. Department Store Upgrade Bonus tokens are placed here. The numbers indicate the total number of customers in the Queue (initially: 2). Customer Queue New Customers will arrive on the map from here. Stations are connected by lines showing potential Components future connections. These lines cannot be used until a player uses theE XPAND action to place track Summary on them, turning them into a rail connection. -

Survey on Multicultural Living in Shinjuku City

No. 13 Publishing Date: June 25, 2008 Published by: Culture, Tourism and International Affairs Division, Region- al and Cultural Affairs Department, Shinjuku City Tel: 03-5273-3504 Fax: 03-3209-1500 1-4-1 Kabukicho, Shinjuku City, Tokyo 160-8484 Please make your inquiries in Japanese when calling the coordinating division. PromotingPromoting HealthHealth withwith SportsSports Shinjuku City has facilities where everyone, from small children to adults, can exercise while having fun. Shinjuku Sports Center Shinjuku Cosmic Sports Center This issue will introduce facilities that you can use to Waseda University Faculty of Science and play sports and improve your health. It is a good idea to Engineering exercise properly and regularly to maintain your health. Meiji-dori Ave. Shinjuku Sports Center Suwa-dori Ave. (3-5-1 Okubo) Ave. Waseda-dori The center is surrounded Toyama Park by the rich greenery of Okubo Sports Plaza To y a m a P a r k a n d h a s Okubo-dori Ave. such facilities as a jogging course, training room, a n d h e a t e d s w i m m i n g Seibu-Shinjuku Line pool as well as a large Takadanobaba Sta. gymnasium where you can Shin-Okubo Sta. enjoy playing basketball or JR Yamanote Line badminton with your friends. Small children are allowed to use the heated swimming pool. Shinjuku Cosmic Sports Center The center offers various classes, such as “ball exercise,” (3-1-2 Okubo) yoga, aqua aerobics, and hula. (Fees are charged.) At each Various facilities are class, professional instructors provide specific advice available, such as a large according to the skill and physical level of each participant. -

Tokyo Subway Ticket

17-100 October 11, 2017 Tokyo Metro will expand the number of locations where its “Tokyo Subway Ticket” special passenger tickets for foreign visitors to Japan can be purchased! Also available for purchase at certain Tokyo Metro commuter pass sales counters starting Monday, October 16, 2017 Starting Monday, October 16, 2017, Tokyo Metro Co., Ltd. (Head Office in: Taito Ward, Tokyo; President: Akiyoshi Yamamura; “Tokyo Metro” below) will make its “Tokyo Subway Tickets,” which allow foreign visitors to Japan to take unlimited rides on all nine Tokyo Metro lines and all four Toei Subway Lines for a total of thirteen lines, available for purchase at certain Tokyo Metro commuter pass sales counters in addition to preexisting sales locations. Until now, these special passenger tickets were only available for purchase at the likes of locally-based travel agencies overseas, airports, hotels and certain traveler information centers. Based on the results of a questionnaire administered to foreign visitors to Japan in which many of them cited their desire to purchase Tokyo Subway Tickets in stations, Tokyo Metro has elected to offer the tickets for purchase at certain commuter pass sales counters Going forward, Tokyo Metro will continue endeavoring to make its railway services more convenient to use for foreign visitors to Japan. For details, please see the below. 1. Commuter Pass Sales Counters Where Tokyo Subway Tickets Are Available for Purchase (15 Locations Across 14 Stations) Ueno Station, Nihombashi Station, Ikebukuro Station, Ginza Station, Shimbashi Station, Shinjuku Station, Ebisu Station, Iidabashi Station, Takadanobaba Station, Akasaka-mitsuke Station, Meiji-jingumae Station <Harajuku>, Shin-ochanomizu Station, Otemachi Station and Tokyo Station *At Ikebukuro Station, Tokyo Subway Tickets can be purchased at the commuter pass sales corners for both the Marunouchi Line and the Yurakucho Line. -

Grand Prix Chiba 2015 Travel Guide

Grand Prix Chiba 2015 Travel Guide. Written by Alan Peng, Khanh Le Thien and Lyle Waldman with contributions from Yoshitoki Sakai and Makino Mitsunori Index. Introduction.............................................................................................................................2 What to prepare for your trip...................................................................................................2 Getting around Tokyo/Chiba.................................................................................................4 The Venue..............................................................................................................................5 How to get to the Venue.........................................................................................................6 How to get to the Staff Hotel...................................................................................................6 Speaking Japanese................................................................................................................6 Places to visit........................................................................................................................11 Things to Eat (Japanese Cuisine).........................................................................................16 Local Gaming Stores.............................................................................................................19 1 Introduction Welcome to Tokyo, Japan’s capital and the most populous metropolis in the -

ITIN Family with 11-Year-Old Daughter, Japan June 2019

ITIN Family with 11-year-old daughter, Japan June 2019 Jizo: protector of children, found in every neighborhood in Japan Client: An American mother and father and 11-year-old daughter. This trip was 90% self guided and almost entirely focused on the interests of the daughter. June 7 (Fri): Arrive Narita International Airport on NH5 (ANA) @ 16:30 (out of LAX) at T1, south wing; you will exit customs at roughly 17:30 and then take the 18:15 Narita Express to JR Shinjuku Station (as below; only a few Narita Express trains go to Shinjuku; this one does). From Shinjuku you can take a short taxi ride to Takadanobaba Station to meet your host or go there by train: the transfer document will provide for both options: platform numbers, etc.). Hotel: AirBnB in Takadanobaba, about 3 km Your Japan Private Tours Ltd. (since 1990) | Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan | Tel: +81-(0)50-5534-4372 | www.kyoto-tokyo-private-tours.com north of Shinjuku. Charges: Yen 5,000/2pax Digital A to B transfer from the airport to Takadanobaba Station. Time Route Fare Seat Fee UsefulLink • Map • Hotel NARITA AIRPORT TERMINAL 1 • Rent-a-car 18:15 Station timetable | Add to favorite Restaurant • LTD. EXP NARITA EXPRESS 44 • Reserved seat: ¥1,700 [89 Min] Train timetable | Interval timetable ¥1,490 SHINJUKU(JR) [ Arrival track No.6 ] 19:44 Add to favorite June 8 (Sat): 10:00-12:30: Nakano: this cathedral-like shotengai shopping arcade (2 km northwest of Shinjuku) is a popular haunt for Tokyo's otaku geek community. -

Owari Toyamasō

An Introduction to Hakoneyama today Birth and history of Toyamasō Toyamasō Garden e height of this articial hill today is . meters above sea Toyamasō was the shimoyashiki (suburban residence) of the e garden of Toyamasō occupied more than of the large level, making it the highest point within the Yamanote Line. Field Museum Guide Toyama Park Owari Tokugawa clan, ruler of Owari domain. Its construction grounds (about , square meters) of this shimoyashiki, began around , on , square meters of land given by the suburban residence of a daimyo (feudal lord). e garden Saishōji Temple in Ushigome. is was the temple of a originally had many eye-catching features built into it, such as a Buddhist nun named Soshin, who was the great-grandmother pond, rock gardens, hills, crop elds, gorges, waterfalls, tea of Chiyo-hime (Princess Chiyo), daughter of the third Shogun shops, shrines and temples. Particularly famous was Omachiya, Owari Tokugawa Iemitsu, and wife of Tokugawa Mitsutomo, the which was a life-size replica of a block of houses in the post-sta- second lord of Owari. e mansion was expanded aer a tion town of Odawarajuku. further , square meters of land was awarded by the Stylistically, the garden is classied as a daimyo garden in the shogunate in . With additional acquisitions of surrounding chisen kaiyu (pond stroll) style. It is atypical, however, in that Toyamasō land, the grounds of the mansion ultimately grew to . its large pond does not have a prominent central island, which hectares, nearly ten times the size of the Tokyo Dome stadium. was normally the focal point of such a pond. -

What to Eat See & Do

ENTERTAINMENT | EVENTS | GUIDES | RESTAURANTS | SHOPPING InTokyo Magazine Number 01 December 2015 東京 FREE Monthly Guide! WHAT TO EAT Bright SEE & Lights, DO Big City Roppongi Shibuya & Tokyo Sparkles Over Shinjuku The Holidays From the publisher of SHIBUYA’S TOP 5 SOUVENIR SHOPS INTOKYO Contents General Manager KIERON CASHELL Editor-in-Chief WHAT TO DO INTOKYO JEFF W. RICHARDS Editorial CHRIS BETROS Welcome to InTokyo, a new monthly guide to one of the world’s greatest cities. In each issue, InTokyo will highlight ALEXANDRA HOMMA popular areas so visitors can explore—without getting lost in translation. Also inside is a monthly calendar of the biggest concerts, exhibitions, plays, musicals and even underground film festivals taking place throughout the ANTHONY JOH month. From info on neighborhood matsuri (festivals) and all-night art events to the best spots to view the annual KELLY WETHERILLE hanami (cherry blossoms) and hanabi (fireworks) across the city, InTokyo will help you experience the city like a local. Art Director NIKLAS WENDT Contributors DAN GRUNEBAUM ALISA KERR KEVIN MCGUE JOANNA PEARCE NAYALAN MOODLEY JUN SATO Sales Director PETER LACKNER PHOTO Account Managers | KEVIN HOLDAWAY GOMAFUKU MOTSU-NABE RENA IWAMA XIAN JIE HIDEAKI KYO REINA OGAWA SEIYA HONGO Production SÉBASTIEN GALLET KEVIN O’NEIL MICHAEL VURCHIO EAT OUT IN ROPPONGI PAGE 16 & 17 Operations MASAHIRO YAGISHITA TAKUYA NOZAWA FIONNA RURI SHIRAI TAKUMI SAKA GIFTS FROM SHIBUYA Cover Photo (& Page 6) COURTESY OF T-ARTS The Area’s Top 5 Souvenir Shops COMPANY LTD. ©&™LUCASFILM LTD. Page 06 Contact EDITORIAL [email protected] RAMEN IN SHINJUKU ADVERTISING [email protected] CITY OF LIGHTS Tel: +81 (0)3 5403-7781 Slurp Up Some Noodles In Fax: +81 (0)3 5403-2775 Enjoy Tokyo’s Holiday Illuminations The Heart Of The City Page 04 Page 10 Published By InTokyo is a monthly guide to the city from GPlus Media, part of the Fuji Sankei Communications Group, the publisher of JapanToday, GaijinPot, Savvy Tokyo & Career Engine. -

Hakoneyama Area Shinjuku Chuo Park Minami-Motomachi Park

No. 9 Publishing Date: June 25, 2007 Published by: Cultural and International Division, Regional and Cultural Affairs Department, Shinjuku City Tel: 03-5273-4069 Fax: 03-3209-1500 1-4-1 Kabukicho, Shinjuku City, Tokyo 160-8472 Please make your inquiries in Japanese when calling the coordinating division. Because the summer is so humid in Japan, places by water or in the shade become especially inviting. Shinjuku may have an image of being an all high-rise building and downtown shopping area, but it also has a lot of places where you can relax next to refreshing waters and surrounded by natural greenery. Why not pack a lunch and head out with the entire family? Toyama Park – Hakoneyama Area (2 and 3 Toyama) Visitors can play to their hearts’ content in this spa- cious park with its rich natural greenery, Jabu- Jabu Splash Pond and at the Seseragi Plaza, and- outdoor play equipment. Hakoneyama, the highest mountain in Shinjuku City (44.6m), is also located in the park. Seseragi-no Sato (1-1 Kami-Ochiai) Hours: Jabu-Jabu Splash Pond – Late July (subject Even small children can safely play at the to change) through August 31 (Fri.), 11 a.m. stream (seseragi in Japanese) located here. to 3 p.m. (Closed on rainy days) Visitors are free to spread a picnic blanket or How to Get There: A 15-minute walk from Waseda Station on the leisure sheet in the spacious grassy area and Tokyo Metro Tozai Line. enjoy a picnic lunch. Also available are slides Seibu-Shinjuku Line and outdoor play equipment.