Requirements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

THE TRIANGLE ARTS NETWORK – Contemporary Art and Transnational Production

THE TRIANGLE ARTS NETWORK – Contemporary Art and Transnational Production by Miriam Aronowicz A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Miriam Aronowicz 2016 The Triangle Arts Network: Contemporary Art and Transnational Production Miriam Aronowicz Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation presents a historical overview and contemporary analysis of the Triangle Arts Network, an international network of artists and arts organizations that promotes the exchange of ideas and innovation within the contemporary arts. It was established in 1982 through a workshop held in Pine Plains, New York and quickly grew into an international network of artist led workshops around the world. More than twenty years later the network continues to grow and includes a roster of ongoing workshops as well as artist led organizations and centres. This dissertation situates Triangle as a major global phenomenon, yet one that operates outside the mainstream artscapes. My research follows the network’s historical links from Saskatchewan, Canada, to New York and onto South Africa. This web-like evolution demonstrates the complexity of global art networks and the fluidity of boundaries needed for contemporary art discourse. This research explores how the movement of ideas, artists and infrastructures complicate our understanding of clearly defined boundaries within contemporary ii art and globalization. Using Actor-Network Theory (ANT) as a metaphor for the Triangle Network, I attempt to unpack the complexities of an art system without objects, a process without product and the entangled relationships between artists, workshops and grassroots models of production. -

The Numinous Land: Examples of Sacred Geometry and Geopiety in Formalist and Landscape Paintings of the Prairies a Thesis Submit

The Numinous Land: Examples of Sacred Geometry and Geopiety in Formalist and Landscape Paintings of the Prairies A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art and Art History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kim Ennis © Copyright Kim Ennis, April 2012. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Art and Art History University of Saskatchewan 3 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A4 Canada i Abstract Landscape painting and formalist painting, both terms taken in their broadest possible sense, have been the predominant forms of painting on the prairie, particularly in Saskatchewan, for several decades. -

Dorothy Knowles's Rural Landscape Painting

DOROTHY KNOWLES'S RURAL LANDSCAPE PAINTING: MODERNITY AND TRADITION IN URBAN SASKATCHEWAN By COLLEEN MARIE SKIDMORE B.A., The University of Saskatchewan, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1989 © Colleen Marie Skidmore, 1989 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, 1 agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date 21 April 1989 DE-6f3/81) ii ABSTRACT Between 1955 and 1965, Saskatchewan painter Dorothy Knowles established her main category and style of production as "painterly" representation of rural landscape. The literature to date attributes the emergence of this practice to Knowles's encounter with Clement Greenberg, the patriarch of formalist criticism, at the 1962 Emma Lake Artists' Workshop. In fact, critic Andrew Hudson has called Knowles's work "the most important art to emerge out of Greenberg's workshop." Herein lies the problem central to this thesis: how did a woman artist negotiate (with critical and market success) the gender constraints of her artistic context while addressing additional social and artistic issues by means of rural landscape painting? Previous examinations have constructed Knowles's landscape work as an autonomous, "feminine" and artist- centred activity. -

Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975

Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975 Rebecca Peabody, editor 1 Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975 Edited by Rebecca Peabody THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM LOS ANGELES Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975 (Getty, 2011) PROOF 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 © 2011 J. Paul Getty Trust Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum on www.gettypublications.org Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.gettypublications.org Marina Belozerskaya, Editor Elizabeth Zozom, Production Coordinator Gary Hespenheide, Designer ISBN: 978-1-60606-069-8 Front cover: Barbara Hepworth, Figure for Landscape, 1960. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum. Gift of Fran and Ray Stark. © Bowness, Hepworth Estate Illustration credits Every effort has been made to contact the owners and photographers of objects reproduced here whose names do not appear in the captions or in the illustration credits. Anyone having further infor- mation concerning copyright holders is asked to contact Getty Publications so this information can be included in future printings. This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for noncommercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors and artists. For any other uses, please refer to the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Terms of Use. Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975 (Getty, 2011) PROOF 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 Contents 4 Foreword Antonia Boström, Penelope Curtis, Andrew Perchuk, Jon Wood 6 Introduction: Trajectories in Sculpture Rebecca Peabody 9 Object Relations: Transatlantic Exchanges on Sculpture and Culture, 1945–1975 John C. -

MANUEL IZQUIERDO Myth, Nature, and Renewal

MANUEL IZQUIERDO Myth, Nature, and Renewal ROGER HULL HALLIE FORD MUSEUM OF ART Willamette University Salem, Oregon distributed by university of washington press seattle and london This book was published in connection with an exhibition arranged by the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University entitled Manuel Izquierdo: Myth, Nature, and Renewal. The dates for the exhibition were January 19 to March 24, 2013, with companion exhibitions entitled Manuel Izquierdo: Maquettes and Small Sculptures and Manuel Izquierdo: Works on Paper, presented from November 17, 2012, to February 10, 2013. Designed by Phil Kovacevich Editorial review by Sigrid Asmus Printed and bound in Canada CONTENTS Front cover and Fig. 2, page 15: Manuel Izquierdo. Cleopatra. 1982. Welded sheet bronze. 23 x 16 x 30 inches. Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon. The Bill Rhoades Collection, a gift in memory of Murna and Vay Rhoades. 2008.023.020 Frontispiece: Manuel Izquierdo in his studio, 1967. Photograph by Alfred A. Monner, courtesy of the Manuel Izquierdo Trust. Back cover and Fig. 93, page 96. Manuel Izquierdo. Center Ring. 1982. Woodcut. 30 x 22 inches. Hallie Ford PREFACE Museum of Art, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon. The Bill Rhoades Collection, a gift in memory of Murna 7 and Vay Rhoades. 2012.003.013 Photo credits: Arbona Fotografo, Figure 4; Bridgeman Art Library, Figure 74; Karen Engstrom, page 132; Paul Foster, Figures 22, 24, 27, 50, 54, 79, 81, 82; Richard Gehrke, Figure 62; Carl Gohs, Figure 68; Aaron Johanson, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Figures 20, 21, 23, 35, 37, 38, 41, 45, 46, 47, 59, 60, 67, 73, 75, 76, 80, 83, 86, 95, 97, 99, 100, 101, 102, 108, and page 119; Manson Kennedy, page 6; Felipe Llerandi, Figure 11; Jim Lommasson, Figure 78; Kevin Longueil, Figure 103; 9 Frank Miller, front cover and Figures 2, 3, 7, 26, 36, 39, 40, 43, 44, 58, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 69, 70, 71, 72, 84, 92, 96, 107; Alfred A. -

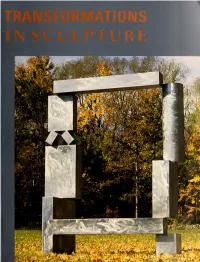

Transformations in Sculpture : Four Decades of American And

H* ,; mSJa t, - '&*JfV. ^HlgrfCV Transformations in Sculpture: Four 1 )ecades oi American and I uropean Art Guggenheim International Exhibition VII TRANSFORMATIONS IN SCULPTURE Four Decades of American and European Art by Diane Waldman I'h is exhibition is suppoi ted by grants from tin Owen Cheatham Foundation and the National I ndowment for the Arts Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Waldman, Diane. Transformations in sculpture. Catalog accompanying the seventh in the Guggenheim interna- tional exhibition series. Bibliography: pp. 251-252 Includes index. 1. Sculpture, American — Exhibitions. 2. Sculpture, Modern — 20th century — United States — Exhibitions. 3. Sculpture, Euro- pean — Exhibitions. 4. Sculpture, Modern — 20th century — Eu- rope — Exhibitions. I. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. II. Title. NB212.W24 1985 735'. 23 85-19584 ISBN: 0-89207-052-8 Published by The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1985 © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1985 Cover: David Smith, Cubi XXVII. March 1965 (cat. no. 15) The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation HONORARY rRUSTEESIN PI RPI II in Solomon R Guggenheim, Justin K fhannhauser, P< ;enheim pri sidi m Petei I awson-Johnston vi( i pri sidi m rhe Right Honorable 1 arl Castle Stewart IKl sills Elaine Dannheisser, Michel David-Weill, Carlo De Benedetti, Joseph W Donner, Robin i handler i Duke, Robert M Gardiner, John S Hilson, Harold W McGraw li Winds I McNeil, Thon Messer, Bonnie Ward Simon, Seymour Sine Stephen C Swid, Rawlcigh Warner, Ji . Michael I Wettach, William I Ylvisaker \l>\ ISOKV BOARD Donald M Blinken, Barrie M Damson, Donald M Feuerstein, Linda LeRoy Janklow, Seyn Klein, Denise Saul, Hannelore Schulhol secretary-treasurer Theodore G Dunker '. -

The Making of an American Sculptor: David Smith Criticism, 1938-1971

THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN SCULPTOR: DAVID SMITH CRITICISM, 1938-1971 MEGHAN LEIA BISSONNETTE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ART HISTORY AND VISUAL CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2014 © Meghan Leia Bissonnette, 2014 Abstract At the time of his death in 1965 at the age of 59, American sculptor David Smith was widely recognized as one of the greatest sculptors of his generation. By then, he had been honoured with a mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, and had represented the United States at Documenta and major biennales at Venice (on two occasions) and São Paolo. Countless studies have analyzed Smith’s career and artistic development, but very little has been written on the published criticism of his work or its larger impact on our understanding of this artist. In this dissertation I examine the historiographic reception of his sculpture from 1938, the year of his first solo exhibition, until 1971 when Rosalind Krauss published Terminal Iron Works, the first monograph on Smith. I trace this reception from the early focus on Smith’s biography and working methods (the biographical paradigm), to the later interest in formal analysis (the formalist paradigm). I further analyze this criticism in the context of artistic developments in the 1940s and 1950s, namely Abstract Expressionist painting and sculpture. In the process, I draw out common themes, tropes and narratives that appear in the criticism on Smith and the Abstract Expressionists. To do so, I engage in a close textual analysis of the exhibition reviews, magazine and newspaper articles, and catalogue essays published during this period. -

26727 Consignor Auction Catalogue Template

CONSIGNOR CANADIAN FINE ART AUCTIONEERS & APPRAISERS Auction of Important Canadian Art November 20, 2018 FALL AUCTION OF IMPORTANT CANADIAN ART LIVE AUCTION TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 20TH AT 7:00 PM GARDINER MUSEUM 111 Queen’s Park (Queen’s Park at Bloor Street) Toronto, Ontario Yorkville Anenue Bedford Rd. Bedford AVENUE RD. AVENUE Cumberland Street ST. GEORGE ST. ST. BLOOR STREET WEST ROYAL GARDINER ONTARIO MUSEUM MUSEUM QUEENS PARK Charles Street West ON VIEW CONSIGNOR GALLERY 326 Dundas Street West, Toronto, Ontario NOVEMBER 1ST TO 17TH Monday to Friday: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Saturdays: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm NOVEMBER 18TH TO 20TH Sunday, November 18th: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm Monday, November 19th: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Tuesday, November 20th: 9:00 am to 1:00 pm 326 Dundas Street West (across the street from the Art Gallery of Ontario) Toronto, Ontario M5T 1G5 416-479-9703 | 1-866-931-8415 (toll free) | [email protected] 4 CONSIGNOR CANADIAN FINE ART | Fall Auction 2018 Rob Cowley President Canadian Art Specialist 416-479-9703 [email protected] Consignor Canadian Fine Art presents an innovative partnership within the Canadian art industry. The venture acts to bridge the services of the retail gallery and auction businesses in Canada with a team of art industry professionals who not only specialize in Lydia Abbott consultation, valuation, and professional presentation of Canadian Vice President art, but who also have unparalleled reputations in providing Canadian Art Specialist exceptional service to the specialized clientele. Mayberry Fine Art 416-479-9703 partner Ryan Mayberry and auction industry veterans Rob Cowley [email protected] and Lydia Abbott act as the principals of Consignor Canadian Fine Art, a hybridized business born in response to the changing landscape of the Canadian art industry. -

Tactility Or Opticality, Henry Moore Or David Smith: Herbert Read and Clement Greenberg on the Art of Sculpture, 1956

105 Tactility or Opticality, Henry Moore or David Smith: Herbert Read and Clement Greenberg on The Art of Sculpture, 1956 David J. Getsy Writing for an American audience in THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK Review just before Thanksgiving in November 1956, the prominent critic Clement Greenberg lashed out at Herbert Read. The occasion for this attack was Read’s 1956 book The Art of Sculpture (fig. 1).1 Greenberg quipped: “Sir Herbert has already betrayed his discomfort with painting; now he betrays it with sculpture.”2 Late in 1953, Read had traveled to the United States to teach for seven months at Harvard University, and to give the Mellon lectures at the National Gallery of Art in the Spring of 1954.3 These lectures were published two years later as The Art of Sculpture. In them, Read put forth a wide-ranging history and theory of sculpture that spanned the gamut of human culture from the pre- historic era to contemporary art. Read had often concerned himself with sculp- ture,4 but in this book he set out to establish a systematic and prescriptive theory of the medium. That is, he argued for a core set of evaluative aesthetic criteria that would apply equally to world sculpture. It was, perhaps, this ambition that incited the wrath of Greenberg. His review was biting and at times petty, but its bile was a direct response to Read’s own aspirations with the book. Read did not let Greenberg’s review pass unre- marked, and the two luminaries would continue to slight each other throughout the next decade.