From the Tooting Commons Management Advisory Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bedside 11 12 03.Indd

Wandsworth SocietetyÈ ˘ ˘˘ ˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ ˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘˘ The Bedside 1971 - FORTY YEARS ON - 2011 Mistletoe istletoe, forming as numerous illustrations show, it was remembered that a vile- evergreen clumps on the association of kissing and tasting tea, made from mistletoe apple and many other mistletoe was well established by which grew on hawthorn, was broad-leaved trees, Victorian times. used to treat measles. Other is a strange plant. It people have collected informa- Mabsorbs water and nutrients from tion on mistletoe being used to its host trees, but as it has chlo- treat hysteria in Herefordshire and rophyll it is able to make its own prevent strokes in Essex. food. If sufficiently mature seeds are Pliny the Elder in the first century used mistletoe can be easily A.D. described Druids in France grown on apple trees. Seeds cutting mistletoe from oak trees extracted from Christmas mistle- in a ritual which involved golden toe are not mature, so it’s neces- sickles, dressing in white cloaks, sary to collect berries in April, slaughtering white bulls. Because squeeze out the seeds and insert of this, mistletoe was considered them in a notch cut in the tree’s to be a pagan plant and banned bark. After a couple of months from churches. small plants emerge, but many of these seem to die within a Mistletoe was associated with year. Survivors grow rapidly and Christmas since the mid-17th live for many years. However, century. By the 19th century this mistletoe produces female and association was well established, male flowers on different plants, and people who had mistletoe- and although I’ve left a trail of bearing trees on their land were mistletoe plants behind me as I’ve bothered by people who raided The situation is complicated by moved around, I haven’t yet man- them. -

Statement of Consultation

Roehampton Supplementary Planning Document Statement of Consultation September 2015 Roehampton SPD Statement of Consultation - September 2015 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Consultation Undertaken 4 3 Overview of Responses 6 4 Representations and the Council’s Response 8 Comments on the Introduction and Background 8 Comments on Key Issues and Challenges 8 Comments on Vision and Strategic Objectives 9 Comments on Core Principle 1 - Housing 9 Comments on Core Principle 2 - Services and Local Centres 12 Comments on Core Principle 3 - Community Facilities 13 Comments on Core Principle 4 - Landscape and Recreation 14 Comments on Core Principle 5 - Heritage 14 Comments on Core Principle 6 - Urban Design 16 Comments on Core Principle 7 - Transport and Access 16 Comments on Core Principle 8 - Sustainability 17 Comments on Delivery 19 Other Comments 19 Appendices 21 1 Consultation Letters 21 2 List of Consultees 22 3 Consultation Web pages 34 4 SPD Summary Boards 37 5 Consultation Advertisement 38 6 E-News Advertisements 39 7 Social Media Advertising 40 8 Consultation Representations 41 2 Wandsworth Council Introduction Local planning authorities may prepare Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) to provide greater detail on Local Plan policies. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) supports the production of SPDs where they can help applicants to make successful applications. To support the implementation of the Council’s Core Strategy (October 2010, second submission version October 2014), Development Management Policies Document (DMPD) (February 2012, second submission version October 2014), Site Specific Allocations Document (SSAD) (February 2012, second submission version October 2014) and the current Local Plan Review, the council is committed to preparing a number of SPDs, which are detailed in the Local Development Scheme (LDS) (2014). -

Wandsworth Local Development Framework

Wandsworth Local Development Framework DMPD & SSAD Proposed Submission Statement of Consultation (Committee version) April 2011 DMPD & SSAD Proposed Submission Statement of Consultation DMPD & SSAD Proposed Submission Consultation Report 1 Introduction 3 2 Consultation Undertaken – who was invited to comment and how they were invited to comment 4 3 Representations and Council's response 7 Development Management Policies Document 7 General comments on DMPD as a whole 7 Chapter 2 – Sustainable Development Principles 9 Chapter 3 – Housing 22 Chapter 4 – Town Centres and Shopping 32 Chapter 5 – Industry, Employment and Waste 41 Chapter 6 – Open Space, the Natural Environment and the Riverside 46 Chapter 7 – Community Facilities 50 Chapter 8 – Transport 51 Appendices 54 Site Specific Allocations Document 56 General Comments on the SSAD as a whole 56 Introduction 58 Chapter 2 - Nine Elms 59 Chapter 3 - Central Wandsworth and the Wandle Delta 75 Chapter 4 - Clapham Junction 83 Chapter 5 - Tooting 87 Chapter 6 - Putney 88 Chapter 7 - Balham 99 Chapter 8 - Roehampton 99 Chapter 9 - Other sites 101 DMPD & SSAD Proposed Submission Statement of Consultation Chapter 10 - Other Thames Riverside sites 102 Appendices 104 4 Next steps 106 DMPD & SSAD Proposed Submission Statement of Consultation 1 Introduction 1.1 The Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 introduced a new system of development plans, requiring the Council’s Unitary Development Plan (2003) to be replaced by a series of documents within the new Local Development Framework (LDF). The first stage is the production of the Core Strategy which sets out the Council's spatial vision, strategic objectives and spatial strategy on how the borough should develop over the next fifteen years along with core policies and information on monitoring and implementation. -

Commons, Heaths and Greens in Greater London Report (2005)

RESEARCH REPORT SERIES no. 50-2014 COMMONS, Heaths AND GREENS IN greater LONDON Report (2005) David Lambert and Sally Williams, The Parks Agency 1 Research Report Series 50- 2014 COMMONS HEATHS AND GREENS IN GREATER LONDON REPORT (2005) David Lambert and Sally Williams, The Parks Agency © English Heritage ISSN 2046-9802 (Online) The Research Report Series incorporates reports by the expert teams within the Investigation & Analysis Division of the Heritage Protection Department of English Heritage, alongside contributions from other parts of the organisation. It replaces the former Centre for Archaeology Reports Series, the Archaeological Investigation Report Series, the Architectural Investigation Report Series, and the Research Department Report Series. Many of the Research Reports are of an interim nature and serve to make available the results of specialist investigations in advance of full publication. They are not usually subject to external refereeing, and their conclusions may sometimes have to be modified in the light of information not available at the time of the investigation. Where no final project report is available, readers must consult the author before citing these reports in any publication. Opinions expressed in Research Reports are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of English Heritage. Requests for further hard copies, after the initial print run, can be made by emailing: [email protected] or by writing to: English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Fort Cumberland Road, Eastney, Portsmouth PO4 9LD Please note that a charge will be made to cover printing and postage. Front Cover: Tooting Common, 1920-1925. Nigel Temple postcard collection. -

A History of Tooting Common the Common Story a History of Tooting Common

The Common Story A History of Tooting Common The Common Story A History of Tooting Common Edited by Katy Layton-Jones Acknowledgements This book has only been made possible due to the many hours contributed by volunteers from the Tooting area over a period of more than four years. A large proportion of the historical research that underpins this book was carried out by these volunteers and special thanks are due to the Tooting History Group for also engaging the local community in the historical research project through guided walks, talks and special events. Particular thanks are extended to Janet Smith for her commitment to the project throughout. Thanks are also extended to: Jim Ballinger Victoria Carroll Pamela Greenwood Deborah Ballinger-Mills Grace Etherington Tessa Holubowicz Anna Blair Paul Gander Susanna Kryuchenkova Philip Bradley Graham Gower Kevin Pinto John Brown Clare Graham Cynthia Pullin List of abbreviations BDANHS Balham & District Antiquarian & Natural History Society HLF Heritage Lottery Fund LA Lambeth Archives LBSCR London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company LCC London County Council LMA London Metropolitan Archive MA Morning Advertiser MBW Metropolitan Board of Works MERL Museum of English Rural Life MPGA Metropolitan Public Gardens Association MOLA Museum of London Archaeology PCOSC Parks, Commons, and Open Spaces Committee of the Metropolitan Board of Works POSC Parks and Open Spaces Committee of London County Council SN The Streatham News and Tooting, Balham, Tulse Hill Advertiser TNA The National Archives WBC Wandsworth Borough Council (formerly Wandsworth Metropolitan Borough Council, WMBC) WBN Wandsworth Borough News WECPR West End and Crystal Palace Railway Company WHS Wandsworth Heritage Service Preface ‘The Common Story’ is part of the Tooting Common Heritage Project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. -

Proposed Orders

Wandsworth Council Consultation on the Introduction or Renewal of Borough-wide Public Space Protection Orders PROPOSED ORDERS Anti-social Behaviour Caused by Drinking Alcohol in a Public Space Order 2020 Proposed legal definition for this order: a) It shall be an offence for any person to refuse to stop drinking alcohol or hand over any containers (sealed or unsealed) which are believed to contain alcohol, when required to do so by a police officer or authorised officer in order to prevent public nuisance or disorder, unless: b) He/She has a reasonable excuse for failing to do so. Offence and Penalty Any person who, without reasonable excuse, fails to comply with the requirements of this Order commits an offence and shall be liable, on summary conviction, to a fine not exceeding level 2 on the standard scale. Use of Novel Psychoactive Substances in a Public Space Order 2020 1. Legal definition for this order: (a) Person(s) within the Restricted Area will not: • Ingest, inhale, inject, smoke, possess or otherwise use intoxicating substances. • Sell or supply intoxicating substances. 2. Intoxicating Substances is given the following definition (does not include alcohol): • Substances with the capacity to stimulate or depress the central nervous system. 3. Exemptions shall apply in cases where the substances are used for a valid and demonstrable medicinal use, given to an animal as a medicinal remedy, are cigarettes (tobacco) or vaporisers or are food stuffs regulated by food health and safety legislation. 4. Persons within this area who breach this prohibition shall surrender intoxicating substances in his/her possession to an authorised person. -

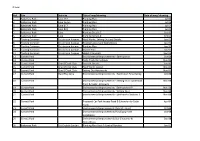

Ref Site Sub-Site Title of Map/Drawing Date of Map/ Drawing 1 Battersea

Official# Ref Site Sub-site Title of map/drawing Date of map/ drawing 1 Battersea Park Lake 1+2 Planting Plan Jul-94 2 Battersea Park Lake 3+4+5 Planting Plan Jul-94 3 Battersea Park Lake 6+7 Planting Plan Jul-94 4 Battersea Park Lake 8+9 Planting Plan Jul-94 5 Battersea Park Lake Planting Details 7 Oct-93 6 Battersea Park Lake Planting Details 8 Oct-93 7 Tooting Common Dr Johnson Avenue Hard Works, Setting Out and Details Jan-91 8 Tooting Common Dr Johnson Avenue Existing Layout and Demolitions Jan-91 9 Tooting Common Dr Johnson Avenue Planting Plan Jan-91 10 Tooting Common Dr Johnson Avenue Master Plan Jan-91 11 Tooting Common Dr Johnson Avenue Sketch Proposals Dec-90 12 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements - Earthworks I Oct-88 13 Garratt Park Cycle Track Demolitions Nov-89 14 Garratt Park One O'Clock Club Sand Pit Details Jan-90 15 Garratt Park One O'Clock Club Hard Works Layout Nov-89 16 Garratt Park One O'Clock Club Setting Out Hardworks Nov-89 17 Garratt Park Hard Play Area Environmental Improvements - Hard Court Resurfacing Oct-88 18 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements - Setting Out II Basketball Nov-88 Pitch & Posts : All Courts 19 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements - Earthworks II P Nov-88 20 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements - Setting Out I Nov-88 21 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements - Earthworks Sections II Nov-88 22 Garratt Park Proposed Car Park Access Road & Extension to Cycle Apr-84 Track 23 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements Overall Layout Oct-88 24 Garratt Park Environmental Improvements Play -

October, 2015 from Our Chair

From our ChairThe London Beekeepers' Association LBKA News, October 2015 LBKA News October, 2015 From our Chair Welcome to the October edition of the newsletter! Richard Glassborow Mark reports on our popular and informative stall at [email protected] the Harvest Stomp in the Olympic Park and Colin re- ports on the short course we ran last month We hear It is autumn and I am going to return to the theme from Esben’s encounter with from log hives whilst on started last month – honey analysis. holiday and Sally’s honey analysis results. Simon gives us a historical perspective on honey prices. And Emily’s This year I tried a little experiment at our teaching api- been finding out about bumble bees. ary in Clapham. We had two productive hives out of the four and I extracted them separately to see if there was From our Chair 1 any difference. The two hives are not much more than Announcements 2 one metre apart and one of them was harvested twice, September’s Monthly Meeting 5 three weeks apart. So we had 3 extractions from two A taste of Beekeeping 6 hives in the same apiary: all three extractions are un- mistakably different in flavour. In fact, the three of us Unexpected Encounter 8 carrying out the extraction thought there was more dif- Honey analysis in N16 9 ference between the two samples from the same colony Harvest Stomp 10 but three weeks apart than the two different colonies. October in the Apiary 12 This would seem to confirm the obvious – a difference October in the Forage Patch 12 in forage being behind the flavour. -

Final Evaluation & Completion Report

Final Evaluation & Completion Report January 2020 Abbreviations used in text AVC Activities and Volunteer Co-ordinator SLSC South London Swimming Club ELC Enable Leisure and Culture Ltd TCHP Tooting Common Heritage Project (’the scheme’) ESL Employment, Skills and Learning TCMAC Tooting Commons Management FoTC Friends of Tooting Common Advisory Committee GIGL Greenspace Information for Greater THG Tooting History Group London (Environmental Records Centre) TWP The Woodfield Project HF National Lottery Heritage Fund WHS Wandsworth Historical Society IE Independent Evaluator LBW London Borough of Wandsworth LWT London Wildlife Trust M&E Monitoring and evaluation Notes: MDR Mid-delivery Review/ Report 1) Prior to ‘rebranding ‘in February 2019 the National M&M/M&MP Management and maintenance/ Lottery Heritage Fund (HF) was known as the plan Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) and most materials relating to TCHP use this initialism. NEET Not in employment, education or 2) The area known as Tooting Common formally training consists of two commons – Tooting Bec Common and S1, S2 The Stage 1 (development) and Stage 2 Tooting Graveney Common. They are together (delivery) of TCHP referred to as the Commons in this report. SG The TCHP Steering Group Codes used to identify respondents to survey & interviews PL = Project lead or Partner representative; V = Volunteer; PA = Participant in one or more TCHP events or activities; NP = Aware of TCHP but not involved in activities; NA = Unaware of the TCHP scheme until approached as part of this evaluation. Richard -

WANDSWORTH HERITAGE FESTIVAL 2018 PROGRAMME of EVENTS 26Th May - 10Th June

WANDSWORTH HERITAGE FESTIVAL 2018 PROGRAMME OF EVENTS 26th May - 10th June In partnership with WANDSWORTH HERITAGE FESTIVAL 2018 PARKS AND OPEN SPACES OF THE BOROUGH Many of the events of this year’s festival celebrate Wandsworth’s open spaces enjoyed by everyone. Wandsworth Park bandstand, c.1910 This programme of events has been brought together by Heritage Wandsworth: the local history and historic environment partnership for the Borough of Wandsworth. WANDSWORTH HERITAGE SERVICE The archives and local history library for the Borough of Wandsworth are located on the first floor of Battersea Library. For more information including opening times please visit our website: www.better.org.uk/archives Historic Images Collection www.boroughphotos.org/wandsworth If you have any access requirements, due to the nature of some of the events and/or restrictions of the venues, please inform the relevant organisation before booking a place. For access requirements relating to events which do not require advance booking, please contact [email protected] or 020 7223 2334 Images in this programme are copyright protected and full details can be supplied on request. Most images are from the collection of Wandsworth Heritage Service. Front cover: Three Island Pond, Wandsworth Common, c.1900 Back cover: Advert for Battersea Park Easter Parade, 1974. Reproduced by kind permission of London Metropolitan Archives 2 Saturday 26th May – 10am-2pm Drop in session: Tooting Common Maps Organised by the Tooting Common Heritage Project View a collection of historical maps and drawings relating to parks and green open spaces in Wandsworth. The focus is Tooting Common but a selection of maps from other green open spaces in the borough will also be made available. -

Organisation Website Or Contact

Organisations represented in the Wildlife Gardening Forum Membership September 2013 Organisation Website or contact C.W Groves and Son Ltd www.grovesnurseries.co.uk Abbey Wood Wildlife Group www.lacv.btck.co.uk/Site%20Information Abingdon Carbon Cutters www.abingdoncarboncutters.org.uk/ Amateur Entomologists' Society www.amentsoc.org/ Amphibian and Reptile Conservation www.arc-trust.org/ Anglian Parks and Wildlife www.anglianparksandwildlife.co.uk/ Anne Harrap Garden Design [email protected] Amphibian and Reptile Group UK www.arguk.org Association of Local Government www.alge.org.uk Ecologists Avon Wildlife Trust www.avonwildlifetrust.org.uk Bat Conservation Trust www.bats.org.uk BBC Gardeners World Mag www.gardenersworld.com/ BBC Two Gardeners World www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006mw1h BBC Nature www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b006sr7c BBC Wildlife www.discoverwildlife.com Bees's Knees Gardens [email protected] Bere Architects www.bere.co.uk Berks, Bucks & Oxon Wildlife Trust www.bbowt.org.uk Biodiversity Unit, N.Ireland Environment Agency Bourne Conservation Group www.bourneconservation.org.uk Brighton & Hove City Council www.brighton-hove.gov.uk Bristol Natural History Consortium www.bnhc.org.uk British Dragonfly Society www.british-dragonflies.org.uk/ British Trust for Ornithology www.bto.org Buglife www.buglife.org.uk Bumblebee Conservation Trust www.bumblebeeconservation.org/ Butterfly Conservation www.butterfly-conservation.org/ Buzzing Gardens www.ywt.org.uk/tags/buzzing-gardens Capel Manor College www.capel.ac.uk/ -

Tooting Common M a N a G E M E N T P L a N

TOOTING COMMON M A N A G E M E N T P L A N Picnickers on Tooling Common c.1900. CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 SURVEY 2 2.1 Introduction 2 2.2 Flora and Fauna 2 2.3 Landscape Features 2 2.4 Circulation 3 2.5 Recreational Use 3 2.6 Underground Services 3 2.7 Artifacts 3 2.8 Microclimate 3 2.9 Geology Soils Topography 3 2.10 History 4 2.11 Consultation 5 2.12 Planning Considerations 5 3.0 ANALYSIS OF PROBLEMS 3.1 Introduction 6 3.2 Movement Patterns/pathways 6 3.2.2 Vehicles 6 3.2.12 Cycling 8 3.2.15 Pathways 8 3.2.21 Horseriding 10 3.2.23 Illegal Access 10 3.2.24 Lighting 11 3.2.27 carparking 11 J.•2.29 Furniture and signs 12 3.2.20 The disabled 13 3.2.31 staff facilities 13 3.3 Recreation 3.3.l Analysis active recreation 14 3.3.2 Football Pitches 14 3.3.10 Tennis 15 3.3.11 Cricket 15 3.3.12 Athletics track 15 3.3.16 The Lido 16 3.3.26 Childrens Play 18 3.3.21 Horseriding 21 3.3.52 Putting Green 23 3.3.53 Trim Trail 23 3.3.54 Cycling 23 3.3.55 Passive Recreation 23 3.3.56 Dogs 23 3.3.57 Fishing 23 3.3.59 The Yachting Pond 24 3.3.62 Events 24 3.3.68 Refreshments 25 3.3.69 Other facilities 25 3.3.76 The Nature Trail 26 3.3.77 Historical Trail 26 3.3.78 Historical features 26 3.3.84 Sculpture 27 3.4 Flora and Fauna/Landscape 28 3.45 Woodlands, trees 29 3.4.11 Recommended species list 31 3.4.23 Wetlands 34 3.4.26 Damp/West Grassland 34 3.4.27 Improved, semi improved grasslands 35 3.4.28 Scrub 35 3.5 Nature conservation education and interpretation 36 3.6 Management Demands and User Restrictions 37 3.7 Surrounding Areas 39 3.8 Buildings