The Benefit of Foresight: Project 2020 in Review 4 of 30 Expert Opinion Was Canvassed at Two Points in the Scenario Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

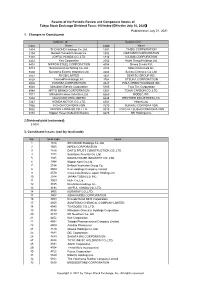

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

Turn for More Solutions

Audio Solutions Installation & Design Services Servers Carts Kiosks Small Form Factor Computers Desktops Lighting Software PRODUCTS Disaster Recovery Products Notebooks & Tablets Telehealth Solutions Interactive Solutions Rugged Telemedicine Kits Temperature Sensing Kiosks Interactive Touchscreen LCDs Sanitizable Technology Wall-Mounted Arms & Cabinets A | COMPUTING SOLUTIONS D | VIRTUALIZATION 1. ACCESSORIES: Belkin, C2G, Case Logic, Kensington, Targus 1. BACKUP & DR: Arcserve, Barracuda, Nakivo, Veeam, Zerto 2. ANTIVIRUS: AVG, BitDefender, Malware Bytes, McAfee, Panda 2. CLOUD: Arcserve, Greencloud, Microsoft Security, Sophos, Symantec, Total Defense, Trend Micro 3. DESKTOP VIRTUALIZATION: Citrix, HVE, NComputing, VMWare 3. DESKTOPS: Howard, Dell, HP, Lenovo, Tangent 4. SERVER VIRTUALIZATION: Hyper-V, VMWare, XenServer 4. MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS: Symantec 5. SERVERS: Howard, Dell, HPE, HVE, Lenovo, Microsoft, Nutanix 5. MOBILE PRESENTATION & CHARGING STATIONS: Aver, Bretford, 6. SOFTWARE-DEFINED STORAGE: Datacore Kwikboost, LocknCharge 7. STORAGE: Dell EMC, HPE, HVE, Lenovo, QNAP, Synology 6. NOTEBOOKS & TABLETS: Howard, Acer, Asus, Cybernet, Dell, Getac, HP, 8. VIRTUAL DESKTOP INFRASTRUCTURE: Citrix, Dell, HVE, Inuvika, LG, Lenovo, Microsoft, Panasonic, Samsung, Tangent, Toshiba, Xplore NComputing, VMWare 7. PRINTERS (2D & 3D): Brother, Canon, Dell, DYMO, Epson, HP, Lexmark, Panasonic, Samsung, Xerox 8. VIRTUAL REALITY: Epson, HP, Oculus Rift, Samsung E | PHYSICAL SECURITY 1. ACCESS CONTROL: 3xlogic, Avue Technologies, Axis, Bosch, B | AUDIOVISUAL SOLUTIONS GeoVision, Isonas, Openpath, MotorCast 2. CLOUD: Brivo, Openpath 1. AUDIO SOLUTIONS: Howard, AMX, Harman, Panasonic 3. DISPLAYS: LG, NEC, Panasonic, Planar, Samsung, Sharp, Sony, ViewSonic 2. BROADCASTING: Panasonic, Sony, Tri-Caster 4. ENCODERS: Axis, Bosch, Hikvision, Panasonic 3. CABLES: C2G, Comprehensive, Crestron, Peerless 5. MASS NOTIFICATION: Singlewire 4. FURNITURE: Middle Atlantic, Spectrum Industries, Worthington Direct 6. MOUNTING & ACCESSORIES: Advidia, Altronix, Avue Technologies, 5. -

Certified by Trend Micro Platforms Independent Hardware Platforms Supporting Trend Micro Software Appliance Deployments

Trend Micro Certified by Trend Micro Platforms Independent Hardware Platforms supporting Trend Micro Software Appliance Deployments TREND MICRO SOFTWARE APPLIANCE SUPPORT What Trend Micro solutions support Software Appliance deployments? The following solutions support the software appliance form factor using specified hardware platforms Abbreviation Solution IWSVA InterScan Web Security Virtual Appliance IMSVA InterScan Messaging Security Virtual Appliance ARM Advanced Reporting and Management (for InterScan Web Security v5.x) Bare Metal Server Platform Matrix Platform Trend Micro Solution IWSVA IMSVA ARM Version 6.5 6.0 5.6 8.x 7.x 1.6 Build 1200 1214 1364 1304 1170 1068 Dell R900 R730 R720 R710 R610 R430 R420 R410 R300 R220 R210 II R200 2950 Series II/III 1950 Series II/III 1850 Series II Hitachi BladeSymphony 1000 HP BL 460 C Generation 1 DL 360 G9 DL 360 G7 2019 Page 1 Trend Micro Certified by Trend Micro Platforms Independent Hardware Platforms supporting Trend Micro Software Appliance Deployments Platform Trend Micro Solution IWSVA IMSVA ARM Version 6.5 6.0 5.6 8.x 7.x 1.6 Build 1200 1214 1364 1304 1170 1068 DL 360 G6 DL 380 G9 DL 380 G7 DL 380 G6 DL 380 G5 DL 385 G6 DL 385 G2 DL 350 G5 DL 388p G8 DL 380p G8 IBM Systems x3550 Systems x3550 M5 NEC Express5800 R120a-1 Express5800 R120RH-1 Resilience ATL 1012 Sun Sunfire X4450 SuperMicro Superserver 1026T Superserver 5016T Bare Metal Server Specifications Platform Hardware Specifications CPU Memory Hard Drive HD Controller NIC Dell PowerEdge R900 2 x Intel X7460 32GB Memory, 300 GB -

GTC-ONE-Minute-Brief-92.Pdf

Equity | Currencies & Commodities | Corporate & Global Economic News & Economic Calendar 29 January 2019 Economic and political news Key indices Bosasa’s Ex-Chief Operating Officer, Angelo Agrizzi, in his testimony, As at 28 1 Day 1 D % WTD % MTD % Prev. month YTD % disclosed that the company agreed to pay ZAR300,000 a month to Jan 2019 Chg Chg Chg Chg % Chg Chg former President, Jacob Zuma’s charitable foundation to shield it from JSE All Share 53767.47 -282.76 -0.52 -0.52 1.95 4.09 1.95 prosecution. (ZAR) JSE Top 40 (ZAR) 47600.25 -292.16 -0.61 -0.61 1.87 4.63 1.87 South Africa’s Transport Minister, Blade Nzimande, stated that the government is keen to see South African Airways (SAA) debt restructured FTSE 100 (GBP) 6747.10 -62.12 -0.91 -0.91 0.28 -3.61 0.28 at the earliest. Meanwhile, SAA Chief Executive Officer, Vuyani Jarana, DAX 30 (EUR) 11210.31 -71.48 -0.63 -0.63 6.17 -6.20 6.17 stated that commercial banks have in principle approved ZAR3.5bn of CAC 40 (EUR) 4888.58 -37.24 -0.76 -0.76 3.34 -5.46 3.34 the funding SAA requires for operating expenses until April. S&P 500 (USD) 2643.85 -20.91 -0.78 -0.78 5.47 -9.18 5.47 Nasdaq Trade union, Solidarity, stated that former South African Broadcasting 7085.69 -79.18 -1.11 -1.11 6.79 -9.48 6.79 Corporation Chief Operating Officer, Hlaudi Motsoeneng, has made his Composite (USD) first payment of ZAR300,000 to the union. -

Partners... More Choices

MORE PARTNERS... MORE CHOICES... 3Dconnexion Alcatel Internetworking AT&T Best Data Products Chatsworth Products, 3M Alera Technologies Atek Electronics, Inc. Black Box Inc. 4XEM Alk Associates ATEN Technologies BlackBerry (RIM) Check Point Software Allied Telesis Atlas Sound Blue Coat Cherry Keyboards A Alsoft Software Attachmate BlueSocket Chief Manufacturing Absolute Software Altec Lansing ATTO Technology BMC Software Ciena Access Data Altova Australian Monitor Bogen Cisco Systems Accuscreen Aluratek Autodesk Box.com Citizen America ACD Systems Amazon Avaya Boxtone Corporation Acer America Ambir Technology AVer Information Brady Industries Citrix Systems Acronis AMD Avery Dennison Brenthaven ClearCube Technology Actiontec Electronics American Avnet Integrated Bretford Clearone ActivePDF Microsystems Avocent Brocade Clearswift Adaptec AMPHENOL Axiohm Brooktrout Clickfree ADC Andrea Products Axiom Brother CMS Peripherals Telecommunications Antec AXIS Communications Buffalo Technologies COBY Addonics APC BUSlink Code Scanners Adesso APG B Cognitive Receipt Adobe AppSense Balt, Inc. C Printers ADTRAN Apricorn Barco C2G Commscope Advanced Media APRIVA Bare Bones Software CA CommVault Services APW Products Barracuda Networks Caldera Component One Aec Software ARCHOS Barrister Global Canary Compsee AeroScout Arista Networks Services Canon CompuCover AirWatch Array Networks Battery Biz Capella Technologies Comtrol Aitech Artromick Battery Technology Case Logic Condusiv Aladdin Knowledge Aruba Networks Bay Dynamics Casio Contour Design Systems -

TOBAM Maximum Diversification All World Developed Ex North America USD

TOBAM Maximum Diversification All World Developed ex North America USD 31/12/2019 Instrument Weight BP PLC 0.10% IDEMITSU KOSAN CO LTD 0.21% INPEX HOLDINGS INC 0.07% JX HOLDINGS INC 0.09% NESTE OIL OYJ 1.16% OMV AG 0.08% SANTOS LTD 0.02% SBM OFFSHORE NV 0.05% TGS NOPEC GEOPHYSICAL CO ASA 0.02% VOPAK 0.02% WOOD GROUP (JOHN) PLC 0.02% AIR LIQUIDE 0.23% AIR WATER INC 0.02% AKZO NOBEL 0.12% ALUMINA LTD 0.03% AMCOR PLC-CDI 0.08% AVON RESOURCES LTD 0.53% BORAL LTD 0.02% CHR HANSEN HOLDING A/S 0.08% DAICEL CHEMICAL INDUSTRIES 0.02% DOWA HOLDINGS CO LTD 0.01% EMS-CHEMIE HOLDING AG-REG 0.03% FLETCHER BUILDING LTD 0.02% FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LTD 0.60% GIVAUDAN-REG 0.16% HITACHI CHEMICAL CO LTD 0.03% HUHTAMAKI OYJ 0.03% ISRAEL CHEMICALS LTD 0.02% JAMES HARDIE INDUSTRIES-CDI 0.07% JFE HOLDINGS INC 0.02% KANSAI PAINT CO LTD 0.03% KURARAY CO LTD 0.03% MITSUBISHI MATERIALS CORP 0.02% NEWCREST MINING LTD 1.35% TOBAM Maximum Diversification All World Developed ex North America USD 31/12/2019 Instrument Weight NIPPON PAINT CO LTD 0.05% NIPPON PAPER INDUSTRIES CO L 0.04% NIPPON SHOKUBAI CO LTD 0.01% NISSAN CHEMICAL INDUSTRIES 0.04% NOF CORP 0.02% NORTHERN STAR RESOURCES LTD 0.66% NOVOZYMES A/S-B SHARES 0.07% OJI PAPER CO LTD 0.03% ORICA LTD 0.02% ORORA LTD 0.02% SARACEN MINERAL HOLDINGS LTD 0.32% SMURFIT KAPPA GROUP PLC 0.04% SYMRISE AG 0.04% TAIHEIYO CEMENT CORP 0.02% TAIYO NIPPON SANSO CORP 0.02% TEIJIN LTD 0.02% THYSSENKRUPP AG 0.04% TORAY INDUSTRIES INC 0.02% WIENERBERGER AG 0.02% ADP 0.04% AENA SA 0.09% ALFA LAVAL AB 0.04% ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS CO LTD -

MITSUI & CO., LTD. Annual Report 2012

MITSUI & CO., LTD. AnnualMITSUI & CO., LTD. Report 2012 MITSUI & CO., LTD. Annual Report 2012 Year ended March 2012 Printed in Japan Contents 002 Mitsui’s History 004 Overview of Results for the Year Ended March 31, 2012 006 Operations that Realize Synergies across Product Lines 008 Message from the CEO: To All of Our Stakeholders President and CEO Masami Iijima provides an overview and explains the goals of the new Medium-term Management Plan “Challenge and Innovation 2014,” as well as Mitsui’s commitment to “high-quality work” and “high-quality profit,” and discusses Mitsui’s spirit of challenge with the aim of being a leading global business enabler. 018 Message from the CFO Chief Financial Officer Joji Okada discusses the investment and loan plan contained in the new Medium-term Management Plan and Mitsui’s financial strategy in light of current financial conditions, as well as the introduction of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). 021 New Medium-term Management Plan Special Feature CHALLENGE AND INNOVATION 2014 We have compiled an overview of the new Medium-term Management Plan “Challenge and Innovation 2014” that was formulated to guide us on our quest to realize Mitsui’s “Long-term Management Vision—Dynamic Evolution as a 21st Century Global Business Enabler” announced in March 2009. Projects 026 01 Energy Segment 027 02 Lifestyle Segment 028 03 Chemicals Segment ©Anadarko Petroleum Corporation A Cautionary Note on Forward-Looking Statements This Annual Report contains statements (including figures) regarding Mitsui & Co., Ltd. (“Mitsui,” “Mitsui & Co.,” “Company” )’s corporate strategies, objectives and views of future developments that are forward-looking in nature and are not simply reiterations of historical facts. -

Trend Micro Deep Discovery Advisor 2.95 Administrator's Guide

Trend Micro Incorporated reserves the right to make changes to this document and to the products described herein without notice. Before installing and using the software, please review the readme files, release notes, and the latest version of the applicable user documentation, which are available from the Trend Micro website at: http://docs.trendmicro.com/en-us/enterprise/deep-discovery-advisor.aspx Trend Micro, the Trend Micro t-ball logo, InterScan, and ScanMail are trademarks or registered trademarks of Trend Micro, Incorporated. All other product or company names may be trademarks or registered trademarks of their owners. Copyright © 2013 Trend Micro Incorporated. All rights reserved. Document Part No.: APEM25797/121119 Release Date: January 2013 Patents pending The user documentation for Trend Micro Deep Discovery Advisor introduces the main features of the software and installation instructions for your production environment. Read through it before installing or using the software. Detailed information about how to use specific features within the software are available in the online help file and the online Knowledge Base at Trend Micro’s website. Trend Micro always seeks to improve its documentation. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions about this or any Trend Micro document, please contact us at [email protected]. Please evaluate this documentation on the following site: http://www.trendmicro.com/download/documentation/rating.asp Table of Contents Preface Preface .............................................................................................................. -

SERVERPROTECT™ for STORAGE Secures Leading Network-Attached Storage Systems

DATASHEET Trend Micro™ SERVERPROTECT™ FOR STORAGE Secures leading network-attached storage systems A single piece of malware or ransomware, like WannaCry or Petya, can spread quickly in Software a networked environment because it is difficult to quarantine infected users. The more Protection Points users who share files by way of servers and storage systems, the greater the risk of • EMC Celerra, Isilon, and VNX/VNXe network damage caused by infected files and of intellectual property theft by data-stealing storage servers malware. Also, the continuous expansion of data capacity can make the completion of • NetApp ONTAP filers and IBM N Series scheduled scans a time-consuming task for administrators. To effectively protect file running Data ONTAP storage systems, enterprises need comprehensive, real-time scanning capabilities that • Hitachi Data Systems NAS take effect as users continuously access files from storage devices on the network. Threat Protection Trend Micro™ ServerProtect™ for Storage, powered by XGen™ security, leverages a • Ransomware blend of cross-generational threat protection techniques to safeguard a wide range of • Viruses network attached storage systems by detecting and removing viruses and spyware in real • Worms time. This comprehensive storage security uses the industry-standard ICAP protocol to • Spyware complement support for traditional RPC communication protocols. To simplify network • Trojans protection for EMC, NetApp, and Hitachi Data Systems storage systems, ServerProtect for Storage provides automatic, -

Anti-Bot Countermeasures in Japan

Joint Workshop on Security 2008, Tokyo Anti-Bot Countermeasures in Japan - Introducing Cyber Clean Center - 25 March 2008 Telecom-ISAC Japan Planning and Coordination Division K. Arimura Copyright©2004-2008 Telecom-ISAC Japan. All Rights Reserved. What is Telecom-ISAC Japan? https://www.telecom-isac.jp/ ● ●Japan’sJapan’s first first ISAC ISAC established established in in July July 2002. 2002. ● ●MembersMembers including including telecommunicati telecommunicationsons carriers carriers collect, collect, analyze analyze and and share share informat informationion and and take take timelytimely measures measures to to ensure ensure trouble trouble free free and and stable stable op operationserations of of services. services. Pres. : KDDI Corp. Members The companies in green are ISPs and carriers. VP’s : NTT Communications Corp., NIFTY Corp. Members : NEC Corp., SOFTBANK TELECOM Corp., Internet Initiative Japan Inc., Hitachi, Ltd., z Cooperative Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd., Oki Electric Industry Co., Ltd., activities and SOFTBANK BB Corp., Yokogawa Electric Corp., Matsushita Electric Works, Ltd., information NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE EAST Corp., sharing are NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE WEST Corp., NTT VISUAL centered on COMMUNICATIONS Corp., KDDI R&D Laboratories, NEC BIGLOBE, Ltd. working NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE Corp., FUJITSU LIMITED groups. Alliance members: Little eArth Corporation Co., Ltd., Intec NetCore Inc., Trend Micro Inc., z The color of T- ISAC-J IBM Japan Co., Ltd./ISS activities are Observers : Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, reflected in the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, etc. WGs. z Responses to DDoS attacks z Wide area monitoring Main z Monitoring of BGP routing information activities of z Measures to counter Antinny WGs 9 Research and Investigation of infection by botnets in Japan 1 9 Measures to counter bot programs / Operation of the website CCC etc. -

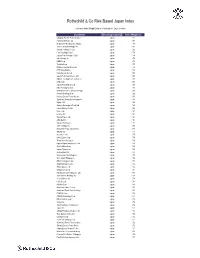

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index Indicative Index Weight Data as of January 31, 2020 on close Constituent Exchange Country Index Weight (%) Chugoku Electric Power Co Inc/ Japan 1.01 Yamada Denki Co Ltd Japan 0.91 McDonald's Holdings Co Japan L Japan 0.88 Sushiro Global Holdings Ltd Japan 0.82 Skylark Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.82 Fast Retailing Co Ltd Japan 0.78 Japan Post Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.78 Ain Holdings Inc Japan 0.78 KDDI Corp Japan 0.77 Toshiba Corp Japan 0.75 Mizuho Financial Group Inc Japan 0.74 NTT DOCOMO Inc Japan 0.73 Kobe Bussan Co Ltd Japan 0.72 Japan Post Insurance Co Ltd Japan 0.69 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Japan 0.69 LINE Corp Japan 0.69 Japan Post Bank Co Ltd Japan 0.68 Nitori Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.67 MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings Japan 0.66 Konami Holdings Corp Japan 0.66 Kyushu Electric Power Co Inc Japan 0.65 Sumitomo Realty & Development Japan 0.65 Fujitsu Ltd Japan 0.63 Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd Japan 0.63 Japan Airlines Co Ltd Japan 0.62 NEC Corp Japan 0.61 Lawson Inc Japan 0.60 Sekisui House Ltd Japan 0.60 ABC-Mart Inc Japan 0.60 Kyushu Railway Co Japan 0.60 ANA Holdings Inc Japan 0.59 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Lt Japan 0.58 ORIX Corp Japan 0.57 Secom Co Ltd Japan 0.57 Seiko Epson Corp Japan 0.56 Trend Micro Inc/Japan Japan 0.56 Nippon Paper Industries Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Suzuki Motor Corp Japan 0.56 Japan Tobacco Inc Japan 0.55 Aozora Bank Ltd Japan 0.55 Sony Financial Holdings Inc Japan 0.55 West Japan Railway Co Japan 0.54 MEIJI Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Sugi Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Tokyo -

Trend Micro Deep Discovery Email Inspector 3.0 Administrator's Guide

Trend Micro Incorporated reserves the right to make changes to this document and to the product described herein without notice. Before installing and using the product, review the readme files, release notes, and/or the latest version of the applicable documentation, which are available from the Trend Micro website at: http://docs.trendmicro.com/en-us/home.aspx/ Trend Micro, the Trend Micro t-ball logo, OfficeScan, Control Manager, and Deep Discovery are trademarks or registered trademarks of Trend Micro Incorporated. All other product or company names may be trademarks or registered trademarks of their owners. Copyright © 2017. Trend Micro Incorporated. All rights reserved. Document Part No.: APEM37857/170505 Release Date: October 2017 Protected by U.S. Patent No.: Patents pending. This documentation introduces the main features of the product and/or provides installation instructions for a production environment. Read through the documentation before installing or using the product. Detailed information about how to use specific features within the product may be available at the Trend Micro Online Help Center and/or the Trend Micro Knowledge Base. Trend Micro always seeks to improve its documentation. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions about this or any Trend Micro document, please contact us at [email protected]. Evaluate this documentation on the following site: http://www.trendmicro.com/download/documentation/rating.asp Table of Contents Preface Preface ................................................................................................................