Carolina Mantis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Genus Metallyticus Reviewed (Insecta: Mantodea)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228623877 The genus Metallyticus reviewed (Insecta: Mantodea) Article · September 2008 CITATIONS READS 11 353 1 author: Frank Wieland Pfalzmuseum für Naturkunde - POLLICHIA-… 33 PUBLICATIONS 113 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Frank Wieland letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 24 October 2016 Species, Phylogeny and Evolution 1, 3 (30.9.2008): 147-170. The genus Metallyticus reviewed (Insecta: Mantodea) Frank Wieland Johann-Friedrich-Blumenbach-Institut für Zoologie & Anthropologie und Zoologisches Museum der Georg-August-Universität, Abteilung für Morphologie, Systematik und Evolutionsbiologie, Berliner Str. 28, 37073 Göttingen, Germany [[email protected]] Abstract Metallyticus Westwood, 1835 (Insecta: Dictyoptera: Mantodea) is one of the most fascinating praying mantids but little is known of its biology. Several morphological traits are plesiomorphic, such as the short prothorax, characters of the wing venation and possibly also the lack of discoidal spines on the fore femora. On the other hand, Metallyticus has autapomor- phies which are unique among extant Mantodea, such as the iridescent bluish-green body coloration and the enlargement of the first posteroventral spine of the fore femora. The present publication reviews our knowledge of Metallyticus thus providing a basis for further research. Data on 115 Metallyticus specimens are gathered and interpreted. The Latin original descriptions of the five Metallyticus species known to date, as well as additional descriptions and a key to species level that were originally published by Giglio-Tos (1927) in French, are translated into English. -

July 2020 Riverside Nature Notes

July 2020 Riverside Nature Notes Dear Members and Friends... by Becky Etzler, Executive Director If you stopped by in the past We are fortunate to have such a wonderful week or so, you will have noticed family of supporters. I have to give a shout out that the Riverside Nature Center to the staff, Riverside Guides, meadow tenders, is fully open and welcoming volunteers, Kerrville Chapter of the Native Plant visitors. There were no banners, Society, Hill Country Master Naturalists, the fireworks, bullhorns or grand Board of Directors and our RNC Members. Each opening celebrations announcing of you have made this difficult time much more our reopening. Let’s call it a “soft bearable, even if we haven’t been able to hug. opening”. Let’s all keep a positive attitude and follow the The staff and I wanted to quietly put to test our example of a wonderfully wise woman, Maggie plans and protocols. Can we control the number Tatum: of people inside? Is our cleaning and sanitizing methods sufficient? Are visitors amenable to our recommendations of mask wearing and physical FRIENDS by Maggie Tatum distancing? Are we aware of all the possible touch points and have we removed potentially Two green plastic chairs hazardous or hard to clean displays? Do we have Underneath the trees, adequate staff and volunteer coverage to keep Seen from my breakfast window. up with cleaning protocols and still provide an They are at ease, engaging experience for our visitors? Framed by soft grey fence. A tranquil composition. Many hours were spent discussing and formulating solutions to all of these questions. -

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument Top left: Melanoplus akinus Top right: Vanessa cardui Bottom left: Elodes sp. Bottom right: Wolf Spider (Family Lycosidae) by David Lightfoot Compiled by Theresa Murphy Nov 2012 In collaboration with Collin Haffey, Craig Allen, David Lightfoot, Sandra Brantley and Kay Beeley WHAT ARE ARTHROPODS? And why are they important? What’s the difference between Arthropods and Insects? Most of this guide is comprised of insects. These are animals that have three body segments- head, thorax, and abdomen, three pairs of legs, and usually have wings, although there are several wingless forms of insects. Insects are of the Class Insecta and they make up the largest class of the phylum called Arthropoda (arthropods). However, the phylum Arthopoda includes other groups as well including Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, shrimps, barnacles, etc.), Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, etc.) and Arachnida (scorpions, king crabs, spiders, mites, ticks, etc.). Arthropods including insects and all other animals in this phylum are characterized as animals with a tough outer exoskeleton or body-shell and flexible jointed limbs that allow the animal to move. Although this guide is comprised mostly of insects, some members of the Myriapoda and Arachnida can also be found here. Remember they are all arthropods but only some of them are true ‘insects’. Entomologist - A scientist who focuses on the study of insects! What’s bugging entomologists? Although we tend to call all insects ‘bugs’ according to entomology a ‘true bug’ must be of the Order Hemiptera. So what exactly makes an insect a bug? Insects in the order Hemiptera have sucking, beak-like mouthparts, which are tucked under their “chin” when Metallic Green Bee (Agapostemon sp.) not in use. -

Mantis Study Group Newsletter, 10 (November 1998)

ISSN 1364-3193 Mantis Study Group Newsletter 10 November 1998 Newsletter Editor Membership Secretary Phil Bragg Paul Taylor 8 The Lane 24 Forge Road Awsworth Shustoke Nottingham Coleshill NG162QP Birmingham B46 2AD Editorial I apologise for the late publication of this newsletter. This is due largely to moving house - the last newsletter was not really affected since it was more or less done before I moved - and starting a new job, and a large number of exhibitions to attend at weekends have caused a backlog of correspondence. Thanks to those of you that have sent in contributions for the newsletter, and apologies to the two people whose articles are still waiting to be typed up, they will appear in the next issue. On the subject of typing up articles, it is helpful if you can submit your articles on disk. However, if you send articles on disk please send them in WordPerfect 5.1 if possible (Users of Word can save files in Wordperfect 5.1 by using the "save as" option under the "File" menu). If this is not possible please send a copy in ASCII (DOS-text). Please note that I cannot read Word files and with my current job I only have access to a machine which can convert the files about once every ten weeks, and that cannot read versions as recent as Word 97. Membership renewals - Paul Taylor. Members will find attached to this Newsletter membership renewal forms for 1999. Members will be pleased to note that there is no increase in membership fees for this coming year. -

Insects on Real Christmas Trees

Insects on Real Christmas Trees Most real Christmas trees are free of insects and other arthropods. However, it is possible that some trees may harbor one or more species. Christmas trees have been a tradition for hundreds of years and bring the beauty and amazing scents of the outdoors into our homes for the holidays. They are also an environmentally friendly choice, as Christmas trees are a renewable resource and can be easily recycled, unlike artificial trees. Real Christmas trees are living trees grown outdoors and, like other living outdoor trees, they can harbor overwintering insects and other arthropods. Some of these arthropods can remain on a tree when it is brought indoors and can become active when exposed to warm indoor temperatures. Depending on the species, the arthropods may remain on the tree or may be attracted to nearby light sources such as windows (during the day) or lamps and other artificial lights (at night). However, because they are associated with living coniferous trees, none of the species that might be introduced into a home via a real Christmas tree are dangerous to the home, its contents, or occupants. Arthropods found in Christmas trees generally overwinter as eggs or adults. Mechanical tree shakers, which are available at some retail lots, or vigorously shaking a tree can dislodge some arthropods, particularly adults. Insect egg masses, such as those laid by mantises, gypsy moths, and spotted lanternfly, can be scraped off the tree trunk or branches. Additionally, bird nests, which are considered decorative and good luck by some people, may contain bird parasites such as mites, and should be removed. -

South Carolina Our Amazing Coast

South Carolina Our Amazing Coast SO0TB CARO LINA REGIONS o ..-- -·--C..,..~.1.ulrt..l• t -·- N O o.u. (South Carolina Map, South Carolina Aquarium’s Standards-based Curriculum, http://scaquarium.org) Teacher Resources and Lesson Plans Grades 3-5 Revised for South Carolina Teachers By Carmelina Livingston, M.Ed. Adapted from GA Amazing Coast by Becci Curry *Lesson plans are generated to use the resources of Georgia’s Amazing Coast and the COASTeam Aquatic Curriculum. Lessons are aligned to the SOUTH CAROLINA SCIENCE CURRICULUM STANDARDS and are written in the “Learning Focused” format. South Carolina Our Amazing Coast Table of Contents Grade 3 Curriculum…………………………………………………………….................1 – 27 Grade 4 Curriculum……………………………………………………………………...28 – 64 Grade 5 Curriculum……………………………………………………………………...65 – 91 SC Background………………...…………………………………………….…………92 – 111 Fast Facts of SC………………...……………………………………………………..112 – 122 Web Resources………………...……………………….……………………………...123 - 124 South Carolina: Our Amazing Coast Grade 3 Big Idea – Habitats & Adaptations 3rd Grade Enduring understanding: Students will understand that there is a relationship between habitats and the organisms within those habitats in South Carolina. South Carolina Science Academic Standards Scientific Inquiry 3-1.1 Classify objects by two of their properties (attributes). 3-1.4 Predict the outcome of a simple investigation and compare the result with the prediction. Life Science: Habitats and Adaptations 3-2.3 Recall the characteristics of an organism’s habitat that allow the organism to survive there. 3-2.4 Explain how changes in the habitats of plants and animals affect their survival. Earth Science: Earth’s Materials and Changes 3-3.5 Illustrate Earth’s saltwater and freshwater features (including oceans, seas, rivers, lakes, ponds, streams, and glaciers). -

Antemninae, Mantidae): a New Lineage of Mantises Exhibiting an Ontogenetic Change in Cryptic Strategy Rodrigues, H., Rivera, J., Reid, N., & Svenson, G

An elusive Neotropical giant, Hondurantemna chespiritoi gen. n. & sp. n. (Antemninae, Mantidae): a new lineage of mantises exhibiting an ontogenetic change in cryptic strategy Rodrigues, H., Rivera, J., Reid, N., & Svenson, G. (2017). An elusive Neotropical giant, Hondurantemna chespiritoi gen. n. & sp. n. (Antemninae, Mantidae): a new lineage of mantises exhibiting an ontogenetic change in cryptic strategy. ZooKeys, 680, 73-104. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.680.11162 Published in: ZooKeys Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright Henrique M. Rodrigues et al. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:06. -

Garden Mastery Tips July 2003 from Clark County Master Gardeners

Garden Mastery Tips July 2003 from Clark County Master Gardeners Praying Mantis Look for this strange-looking humongous bug in the yard late summer. There are over 1800 species, mostly tropical. Three are native in North America: the Chinese mantis, Tenodera sinensis, the Carolina mantis, Stagmomantis carolina and the European mantis, Mantis religiosa. The mantis, also known as mantid is most closely related to grasshoppers and cockroaches. The common name comes from the manner in which they hold up the forepart of their body, with the front legs folded as if in prayer. They range from 2 to 6 inches in length and are varying shades of brown and green. It is uncanny how they camouflage themselves in the surrounding foliage. They can resemble leaves, sticks and even flowers. This helps hide them from their potential prey, as well as their enemies. Mantids move rather slowly, swaying back and forth, mimicking foliage in the breeze. They can fly, but not long distances, preferring to move from one perch to another. Mantids tend to fly more at night which brings them to the attention of bats who see them as a source of food. Some mantids have actually learned to hear the sonar used by the bats to navigate and are able to stall their flight literally dropping out of sight of the bats’ perception, thus escaping the meal they were intended to be. Other than bats, birds and spiders are their main predators. The praying mantis is strictly a meat eater who enjoys moths, beetles, horseflies, leaf hoppers, aphids, and other mantises, even animals larger than themselves, such as frogs, lizards, and young snakes. -

Species List for Garey Park-Inverts

Species List for Garey Park-Inverts Category Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Abundance Category Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Abundance Arachnid Araneae Agelenidae Funnel Weaver Common Arachnid Araneae Thomisidae Misumena vatia Goldenrod Crab Spider Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Araneus miniatus Black-Spotted Orbweaver Rare Arachnid Araneae Thomisidae Misumessus oblongus American Green Crab Spider Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Argiope aurantia Yellow Garden Spider Common Arachnid Araneae Uloboridae Uloborus glomosus Featherlegged Orbweaver Uncommon Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Argiope trifasciata Banded Garden Spider Uncommon Arachnid Endeostigmata Eriophyidae Aceria theospyri Persimmon Leaf Blister Gall Rare Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Gasteracantha cancriformis Spinybacked Orbweaver Common Arachnid Endeostigmata Eriophyidae Aculops rhois Poison Ivy Leaf Mite Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Gea heptagon Heptagonal Orbweaver Rare Arachnid Ixodida Ixodidae Amblyomma americanum Lone Star Tick Rare Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Larinioides cornutus Furrow Orbweaver Common Arachnid Ixodida Ixodidae Dermacentor variabilis American Dog Tick Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Mangora gibberosa Lined Orbweaver Uncommon Arachnid Opiliones Sclerosomatidae Leiobunum vittatum Eastern Harvestman Uncommon Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Mangora placida Tuft-legged Orbweaver Uncommon Arachnid Trombidiformes Anystidae Whirligig Mite Rare Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Mecynogea lemniscata Basilica Orbweaver Rare Arachnid Eumesosoma roeweri -

An Elusive Neotropical Giant, Hondurantemna Chespiritoi Gen. N

An elusive Neotropical giant, Hondurantemna chespiritoi gen. n. & sp. n. (Antemninae, Mantidae): a new lineage of mantises exhibiting an ontogenetic change in cryptic strategy Rodrigues, H., Rivera, J., Reid, N., & Svenson, G. (2017). An elusive Neotropical giant, Hondurantemna chespiritoi gen. n. & sp. n. (Antemninae, Mantidae): a new lineage of mantises exhibiting an ontogenetic change in cryptic strategy. ZooKeys, 680, 73-104. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.680.11162 Published in: ZooKeys Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright Henrique M. Rodrigues et al. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Mantids of Colorado Fact Sheet No

Mantids of Colorado Fact Sheet No. 5.510 Insect Series|Home and Garden by W. Cranshaw* Mantids are some of the most distinctive Quick Facts and well-recognized of all the insect groups. All mantids are predators that feed on various • Mantids are large, distinctive insects, including some pest species. Seven insects that feed on other species of mantids are found in Colorado insects, including some pests. (Table 1), five of which are native to the state. Mantids are very distinctive insects. All • All mantids survive winter in have front legs which are large and well- the egg stage, within a large designed for grasping prey. The segment of egg case (ootheca). the body containing these legs (prothorax) • There are seven kinds is very elongated as is the overall body form. of mantids that occur in Mantids also have the ability to easily turn Colorado, five that are native their heads in order to see in all directions and have widely spaced eyes that give them to the state and two that are excellent binocular vision. introduced species. • The most commonly General Life History encountered mantid in much of the state is the European Mantids survive winter as eggs. The eggs are laid in a case, known as an ootheca, and mantid, which may be brown each contains several dozen to over a 100 or green. eggs. A foamy material covers the oothecal as • Egg cases of the Chinese it is being produced and this then hardens to mantid are commonly sold protect and insulate the eggs. These egg cases through nurseries and garden are attached to solid surfaces such as rocks, catalogs. -

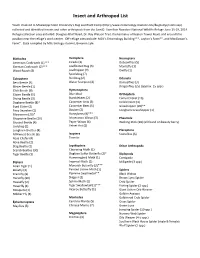

Insect and Arthropod List

Insect and Arthropod List Youth involved in Mississippi State University’s Bug and Plant Camp (http://www.entomology.msstate.edu/bugcamp/index.asp) collected and identified insects and other arthropods from the Sam D. Hamilton Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge June 15-19, 2014. Refuge collection sites included: Douglass Bluff Road, Dr. Ray Watson Trail, the terminus of Keaton Tower Road, and around the pavilion near the refuge’s work center. Off-refuge sites include: MSU’s Entomology Building***, Layton’s Farm**, and MacGowan’s Farm*. Data compiled by MSU biology student, Breanna Lyle. Blattodea Hemiptera Neuroptera American Cockroach (1)*** Cicada (1) Dobsonflies (5) German Cockroach (2)*** Leaffooted Bug (3) Mantisfly (1) Wood Roach (3) Leafhopper (9) Owlfly (1) Spittlebug (7) Coleoptera Stinkbug (2) Odonata Bess Beetle (4) Water Scorpion (4) Damselflies (3) Blister Beetle (1) Dragonflies (25) (approx. 15 spp.) Click Beetle (9) Hymenoptera Clown Beetle (5) Blue Mud Orthoptera Diving Beetle (3) Bumblebees (2) Camel Cricket (16) Dogbane Beetle (8)* Carpenter Ants (3) Field Cricket (3) Eyed Elater (2) Carpenter Bees (5) Grasshopper (20)** Fiery Searcher (1) Dauber (2) Longhorn Grasshopper (1) Glowworm (20)* Honeybees (9)*** Grapevine Beetle (10) Ichneumon Wasps (3) Phasmida Ground Beetle (4) Paper Wasps (4) Walking Stick (18) (all found on beauty berry) Ladybug (1) Velvet Ant (2) Longhorn Beetles (4) Plecoptera Milkweed Beetle (6) Isoptera Stoneflies (6) Rose Chafer (4) Termite Rove Beetle (2) Stag Beetle (2) Lepidoptera Other Arthropods: