Outside the Net: Intersectionality and Inequality in the Fisheries of Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Gayathri LOKUGE and Dorothea HILHOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Valvai Chapter - Seafaring Town of Valvai

History of Valvai Chapter - Seafaring Town of Valvai Reprinted from: Subject VVT boat arrived in USA Posted by Ranithevan Posted on Sun Oct 18 15:09:27 1998 Annapoorani built in Valvai by Valvettithurai Shipbuilding Experts On its way to USA renamed as Florence C Robinson VALVETTITHURAI's SEA FARERS -1 GLOUCESTER., Massachusetts USA. August 1, 1938. We have folk stories and mythologies. And then, we have a history most people have either forgotten or are not aware of. This is a real-life story about one of the last sailing vessels built in Valvettithurai, making a long journey to the Atlantic Coast of United States. But, closer to home, these vessels made their home ports at Valvettithurai and Parithithurai(Pt. Pedro). Most of them, while being built and operated by sailors from Valvettithurai, were owned by the wealthy Chetty families from Tamil Nadu. The rest were owned by the Chetty traders who had settled in Valvettithurai since the opening of secure sea lanes in Indian Ocean by the Porthuguese(from Arab & Far Eastern pirates). (They might have been there since before Chola's time.) Building and maintaining large ocean going vessels in those days required a larg sum of capital; it can be afforded by only few families who had already well established themselves as reputed trading families. These vessels, up to World War 2, plied the sea-routes the Tamils had used for centuries before. They made ports-of-call in South India, Vizhakapattinam to Cochin(occasionaly even Calcutta), Rangoon, Far Eastern destinations, ports in Middle East(such as Eden). -

The Government of the Democratic

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 DEPARTMENT OF STATE ACCOUNTS GENERAL TREASURY COLOMBO-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. Note to Readers 1 2. Statement of Responsibility 2 3. Statement of Financial Performance for the Year ended 31st December 2019 3 4. Statement of Financial Position as at 31st December 2019 4 5. Statement of Cash Flow for the Year ended 31st December 2019 5 6. Statement of Changes in Net Assets / Equity for the Year ended 31st December 2019 6 7. Current Year Actual vs Budget 7 8. Significant Accounting Policies 8-12 9. Time of Recording and Measurement for Presenting the Financial Statements of Republic 13-14 Notes 10. Note 1-10 - Notes to the Financial Statements 15-19 11. Note 11 - Foreign Borrowings 20-26 12. Note 12 - Foreign Grants 27-28 13. Note 13 - Domestic Non-Bank Borrowings 29 14. Note 14 - Domestic Debt Repayment 29 15. Note 15 - Recoveries from On-Lending 29 16. Note 16 - Statement of Non-Financial Assets 30-37 17. Note 17 - Advances to Public Officers 38 18. Note 18 - Advances to Government Departments 38 19. Note 19 - Membership Fees Paid 38 20. Note 20 - On-Lending 39-40 21. Note 21 (Note 21.1-21.5) - Capital Contribution/Shareholding in the Commercial Public Corporations/State Owned Companies/Plantation Companies/ Development Bank (8568/8548) 41-46 22. Note 22 - Rent and Work Advance Account 47-51 23. Note 23 - Consolidated Fund 52 24. Note 24 - Foreign Loan Revolving Funds 52 25. -

Municipal and Urban Councils of Sri Lanka

Type of Council Province District Municipality Area (km²) Population Municipal Western Colombo Colombo 37 693,596 Municipal Western Colombo Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia 21 233,290 Municipal Western Colombo Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte 17 125,270 Municipal Western Colombo Kaduwela 87 250,668 Municipal Western Colombo Moratuwa 23 191,634 Municipal Western Gampaha Negombo 31 141,520 Municipal Western Gampaha Gampaha 38 67,990 Municipal North Western Kurunegala Kurunegala 11 31,299 Municipal Central Kandy Kandy 27 125,182 Municipal Central Matale Matale 9 48,225 Municipal Central Matale Dambulla 54 26,000 Municipal Central Nuwara Eliya Nuwara Eliya 12 35,081 Municipal Uva Badulla Badulla 10 42,066 Municipal Uva Badulla Bandarawela 27 36,778 Municipal Southern Galle Galle 17 101,159 Municipal Southern Matara Matara 13 90,000 Municipal Southern Hambantota Hambantota 83 22,978 Municipal Sabaragamuwa Ratnapura Ratnapura 20 52,000 Municipal North Central Anuradhapura Anuradhapura 36 109,175 Municipal Northern Jaffna Jaffna 20 90,279 Municipal Eastern Batticaloa Batticaloa 75 92,120 Municipal Eastern Ampara Kalmunai 23 120,000 Municipal Eastern Ampara Akkaraipattu 7 39,223 Urban Southern Galle Ambalangoda Urban Eastern Ampara Ampara Urban Sabaragamuwa Ratnapura Balangoda Urban Western Kalutara Beruwala Urban Western Colombo Boralesgamuwa Urban Northern Jaffna Chavakachcheri Urban North Western Puttalam Chilaw Urban Sabaragamuwa Ratnapura Embilipitiya 58,371 Urban Eastern Batticaloa Eravur Urban Central Kandy Gampola Urban Uva Badulla Haputale Urban Central -

Department of Samurdhi Development Associate Officer Service Category (MN-4) Applied for 1 (01) Efficiency Bar Examination for S

Department of Samurdhi Development Associate Officer Service Category (MN-4) applied for 1st (01) Efficiency Bar Examination for Samurdhi Managers List of Examination Candidates No Name Permanent address N.I.C. No. sex Medium T.P. No. 1 Abdul Gafoor Amanullah 14/1, Beach Road, Pottuvil 21. 198218301393 Male Tamil 0779067222 2 Alagarsamy Dhivyanisha 66, Laikka Gnanam Village, Parasankulam, Puliyankulam. 868634499V Female Tamil 0774262173 3 Alex Roche Josvin Regeevarani 32/6, Periyagamam, Eluthur, Mannar. 807511050V Female Tamil 0776450804 4 Alimuhamed Nihara Palliyadi Road, Eravur 02A 755013315V Female Tamil 0759160745 5 Anantharaja Kavitha Ariyanayagam Road, Thirukovil 02. 847804726V Female Tamil 0777218478 6 Anton Nesaratnam Bonavensor Fernando 4th Vaddaram, Pesalai, Mannar. 861992926V Male Tamil 0778737146 7 Antony Regi Lenil Revin Croos 4th Vaddaram, Pesalai, Mannar. 853061190V Male Tamil 0772363545 8 Antron Joseph Ligourius Thuram 8th Vaddaram, Pesalai, Mannar. 872141243V Male Tamil 0772243366 9 Anusha Kajandran 19, Thaalvupadu Road, Mannar. 855503271V Female Tamil 0779323631 10 Arunantha Sujathashini 295, Thirunagar North, Kilinochchi 766282091V Female Tamil 0772456918 11 Balasamy Davidson Elroy 472/33A, Makola South, Makola. 198328504387 Male Tamil 0763961042 12 Balasubramaniyam Puwaneshwary 461, Ampal Kulam, Killinochchi. 816144515V Female Tamil 0772588341 13 Ehamparanathan Mangaleswary Viji Road, Mulankavil, Poonagary. 828203258V Female Tamil 0777249234 14 Francis Josepien Golda 32, Periya Uppodai, Batticaloa. 837941962V Female -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Jaffna District – 2007

BASIC POPULATION INFORMATION ON JAFFNA DISTRICT – 2007 Preliminary Report Based on Special Enumeration – 2007 Department of Census and Statistics June 2008 Foreword The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), carried out a special enumeration in Eastern province and in Jaffna district in Northern province. The objective of this enumeration is to provide the necessary basic information needed to formulate development programmes and relief activities for the people. This preliminary publication for Jaffna district has been compiled from the reports obtained from the District based on summaries prepared by enumerators and supervisors. A final detailed publication will be disseminated after the computer processing of questionnaires. This preliminary release gives some basic information for Jaffna district, such as population by divisional secretary’s division, urban/rural population, sex, age (under 18 years and 18 years and over) and ethnicity. Data on displaced persons due to conflict or tsunami are also included. Some important information which is useful for regional level planning purposes are given by Grama Niladhari Divisions. This enumeration is based on the usual residents of households in the district. These figures should be regarded as provisional. I wish to express my sincere thanks to the staff of the department and all other government officials and others who worked with dedication and diligence for the successful completion of the enumeration. I am also grateful to the general public for extending their fullest co‐operation in this important undertaking. This publication has been prepared by Population Census Division of this Department. D.B.P. Suranjana Vidyaratne Director General of Census and Statistics 6th June 2008 Department of Census and Statistics, 15/12, Maitland Crescent, Colombo 7. -

A Study of Violent Tamil Insurrection in Sri Lanka, 1972-1987

SECESSIONIST GUERRILLAS: A STUDY OF VIOLENT TAMIL INSURRECTION IN SRI LANKA, 1972-1987 by SANTHANAM RAVINDRAN B.A., University Of Peradeniya, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1988 @ Santhanam Ravindran, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date February 29, 1988 DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT In Sri Lanka, the Tamils' demand for a federal state has turned within a quarter of a century into a demand for the independent state of Eelam. Forces of secession set in motion by emerging Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism and the resultant Tamil nationalism gathered momentum during the 1970s and 1980s which threatened the political integration of the island. Today Indian intervention has temporarily arrested the process of disintegration. But post-October 1987 developments illustrate that the secessionist war is far from over and secession still remains a real possibility. -

(DFAT) Country Information Report on Sri Lanka of 4 November 2019

July 2020 Comments on the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) Country Information Report on Sri Lanka of 4 November 2019 Contents About ARC ................................................................................................................................... 2 Introductory remarks on ARC’s COI methodology ......................................................................... 3 General methodological observations on the DFAT Country report on Sri Lanka ............................ 5 Section-specific observations on the DFAT Country report on Sri Lanka ....................................... 13 Economic Overview, Economic conditions in the north and east ........................................................ 13 Security situation, Security situation in the north and east ................................................................. 14 Race/Nationality; Tamils ....................................................................................................................... 16 Tamils .................................................................................................................................................... 20 Tamils: Monitoring, harassment, arrest and detention ........................................................................ 23 Political Opinion (Actual or Imputed): Political representation of minorities, including ethnic and religious minorities .............................................................................................................................. -

Humanitarian Operation Factual Analysis July 2006 – May 2009

HUMANITARIAN OPERATION FACTUAL ANALYSIS JULY 2006 – MAY 2009 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA HUMANITARIAN OPERATION FACTUAL ANALYSIS JULY 2006 – MAY 2009 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE JULY 2011 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA Humanitarian Operation—Factual Analysis TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 A. Overview of this Report 1 B. Overview of the Humanitarian Operation 1 PART ONE II. BACKGROUND 4 A. Overview of the LTTE 4 B. LTTE Atrocities against Civilians 6 C. Use of Child Soldiers by the LTTE 10 D. Ethnic Cleansing Carried out by the LTTE 10 E. Attacks on Democracy by the LTTE 11 F. The Global Threat posed by the LTTE 11 G. Proscription of the LTTE 12 III. SIZE AND SCOPE OF THE LTTE 13 A. Potency of the LTTE 13 B. Number of Cadres 14 C. Land Fighting Forces 14 D. The Sea Tiger Wing 17 E. The Air Tiger Wing 20 F. Black Tiger (Suicide) Wing 22 G. Intelligence Wing 22 H. Supply Network 23 I. International Support Mechanisms 25 J. International Criminal Network 27 – iii – Humanitarian Operation—Factual Analysis Page IV. GOVERNMENT EFFORTS FOR A NEGOTIATED SETTLEMENT 28 A. Overview 28 B. The Thimpu Talks – July to August 1985 29 C. The Indo-Lanka Accord – July 1987 30 D. Peace Talks – May 1989 to June 1990 32 E. Peace Talks – October 1994 to April 1995 33 F. Norwegian-Facilitated Peace Process – February 2002 to January 2008 35 G. LTTE Behaviour during 2002–2006 37 PART TWO V. RESUMPTION OF HOSTILITIES 43 VI. THE WANNI OPERATION 52 VII. -

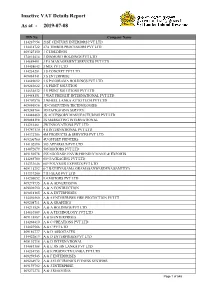

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

Medical Treatment and Healthcare

Country Policy and Information Note Sri Lanka: Medical treatment and healthcare Version 1.0 July 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) for decision makers handling cases where a person claims that to remove them from the UK would be a breach Articles 3 and / or 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) because of an ongoing health condition. It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of healthcare in Jamaica. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency and traceability. The structure and content of the country information section follows a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to this note. All information included in the note was published or made publicly available on or before the ‘cut-off’ date(s) in the country information section. Any event taking place or report/article published after these date(s) is not included. All information is publicly accessible or can be made publicly available, and is from generally reliable sources. Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include: • the motivation, purpose, knowledge and experience of the source • how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used • the currency and detail of information, and • whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources. -

Download 3.09 MB

Second Integrated Road Investment Program Tranche 3 (PFRR SRI 50301-004) Facility Administration Manual Project Numbers: 50301-002/003/004 MFF Number: 0102 Loan Numbers: 3579/3580/3851/xxxx April 2021 Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: Second Integrated Road Investment Program ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank COVID-19 – coronavirus disease CRC – conventional road contract DMF – design and monitoring framework EARF – environmental assessment and review framework EMP – environmental management plan ESDD – Environment and Social Development Division EWCD – elderly, women, children, and disabled FIDIC – International Federation of Consulting Engineers GAP – gender action plan ICB – international competitive bidding IEE – initial environmental examination IPP – indigenous peoples plan IPPF – indigenous peoples planning framework iRoad 2 – Second Integrated Road Investment Program LKR – Sri Lanka rupee MFF – multitranche financing facility MOHW – Ministry of Highways NCB – national competitive bidding PBM – performance-based maintenance PIC – project implementation consultant PIU – project implementation unit PMU – project management unit PPMS – project performance management system RDA – Road Development Authority RRP – report and recommendation of the President SLRs – Sri Lanka rupees CONTENTS I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. IMPLEMENTATION PLANS 1 A. Project Readiness Activities 1 B. Overall Project Implementation Plan 3 III. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 4 A. Project Implementation Organizations: Roles and Responsibilities 4 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 5 C. Project Organization Structure 6 IV. COSTS AND FINANCING 12 A. Cost Estimates Preparation and Revisions 13 B. Key Assumptions 14 C. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category and Financier – Facility 14 D. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds for Tranches 1, 2, and 3 18 E. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year 20 F.