Geotechnical Resistance Factors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineering Bulletin 07-009

To: New York State Department of EB Transportation ENGINEERING 07-009 BULLETIN Expires one year after issue unless replaced sooner Title: HIGHWAY DESIGN MANUAL (HDM) REVISION NO. 52 CHAPTER 9 - SOILS, WALLS, AND FOUNDATIONS CHAPTER 20.00 –CANTILEVER AND GRAVITY WALLS Distribution: Approved: Manufacturers (18) Surveyors (33) Local Govt. (31) Consultants (34) Agencies (32) Contractors (39) /s/Daniel D’Angelo________________ 3/2/07____ ____________( ) Daniel D’Angelo, P.E. Date Deputy Chief Engineer, Design ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION: Effective Date: This Engineering Bulletin (EB) is effective upon signature. Superseded Issuance(s): No Engineering Instructions or EBs are superseded by this EB. PURPOSE: To announce the availability of Revision No. 52 to the HDM and to rescind HDM Chapter 20.00 –Cantilever and Gravity Walls. TECHNICAL INFORMATION: Chapter 9. HDM users should replace their entire existing Chapter 9 dated June 7, 1995, and revised July 9, 2004, with the updated version dated March 2, 2007. Chapter 9 has been revised to clarify, update, and add material. Although the entire chapter is being issued, not all material has been revised. Noteworthy changes are as follows: . Section 9.3 “Soil and Foundation Considerations” was expanded to include the following: “Embankment Foundation.” This subsection combines previous subsections including “Unsuitable Material” and “Unstable Material.” “Water Quality.” This subsection replaces the previous “Erosion and Sedimentation” subsection. “Excavation Protection and Support.” This subsection replaces the previous “Trench, Culvert, and Structure Excavation” subsection. “Controlled Low-Strength Material (CLSM).” This is a new subsection. “Contract Information” was moved from Section 9.4 to Section 9.7 and Section 9.4 is retitled “Retaining Walls and Reinforced Soil Slopes and Walls.” This section incorporates the former HDM Chapter 20.00 “Cantilever and Gravity Walls.” . -

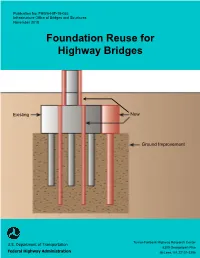

Foundation Reuse for Highway Bridges

Publication No. FHWA-HIF-18-055 Infrastructure Office of Bridges and Structures November 2018 Foundation Reuse for Highway Bridges Existing New Ground Improvement Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center U.S. Department of Transportation 6300 Georgetown Pike Federal Highway Administration McLean, VA 22101-2296 FOREWORD Given the high percentage of deteriorated or obsolete bridges in the national bridge inventory, the reuse of bridge foundations may be a viable option that can present a significant cost savings in bridge replacement and rehabilitation efforts. The potential time savings associated with foundation reuse can, in turn, reduce mobility impacts and increase the economic viability and sustainability of a project. However, existing foundations may have uncertain material properties, geometry, or details that impact the risks associated with reuse. Unlike a new foundation, an existing foundation may have been damaged, may not have sufficient capacity, and may have limited remaining service life due to deterioration. Assessment of these issues as well as foundation strengthening and repair measures and innovative approaches to optimize loading are discussed in this report. To better demonstrate the engineering assessment of key integrity, durability and load carrying capacity issues, the report contains fifteen (15) case examples where foundation was reused by the owner agencies. On new construction, the report looks ahead and includes discussions on foundation design with consideration for reuse. Cheryl Allen Richter, P.E., Ph.D. Director, Office of Infrastructure Research and Development Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. -

A Qljarter Century of Geotechnical Researcll

A QlJarter Century of Geotechnical Researcll PUBLICATION NO. FHWA-RD-98-139 FEBRUARY 1999 1111111111111111111111111111111 PB99-147365 \c-c.J/t).:.. L~.i' . u.s. D~~~~~~~Co~~~~~erce~ Natronal_Tec~nical Information Service u.s. DepartillCi"li of Transportation Spnngfleld, Virginia 22161 Research, Development & Technology Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center 6300 Georgetown Pike McLean, VA 22101-2296 FOREWORD This report summarizes Federal Highway Administration (FHW!\) geotechnical research and development activities during the past 25 years. The report incl!Jde~: significant accomplishments in the areas of bridge foundations, ground improvenl::::nt, and soil and rock behavior. A fourth category included important miscellaneous efrorts tl'12t did not fit the areas mentioned. The report vlill be useful to re~earchers and praGtitior,c:;rs in geotechnology. --------:"--; /~ /1 I~t(./l- /-~~:r\ .. T. Paul Teng (j Director, Office of Infrastructure Research, Development. and Technologv NOTiCE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States G~)\fernm8nt assumes no liahillty for its contt?!nts or use thereof. Thir. report dor~s not constiil)tl":: a standard, specification, or regu!p,tion. The; United States Government does not endorse products or n18;1ufaGturers, Traderrlc,rks or nianufacturers' narl1es appear in thi;-, report only bec:8'I)Se they arc considered essential to tile object of the document. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-RD-98-139 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date A Quarter Century of Geotechnical Research February 1999 6. Performing Organization Code ). -

LOADTEST Dynamic Load Testing (DLT)

LOADTEST Dynamic Load Testing (DLT) INTRODUCTION RESULTS Dynamic load testing can be an attractive cost The measured pile head signals are analysed in effective alternative to traditional full scale static real time to provide: load testing. Instead of costly, time consuming • an estimate of the soil resistance proof loading using kentledge or anchor piles, mobilised during the test. the technique uses a heavy falling weight such • determination of maximum stresses in as a piling hammer to impart a short duration the pile and shaft integrity. impact to the pile head, whilst monitoring the • measurement of the overall operating pile response using attached transducers. The efficiency of the hammer and its test generates data required by the foundation coupling to the pile head. designer to provide assurance on the relative Additional analysis of each set of dynamic test capacity of the foundation and can usually data can be performed using the CAPWAP or provide additional information that can be DLTWAVE pile driving simulation computer difficult to obtain via static load testing. programs. These programs uses an iterative solution technique to optimise the parameters DESCRIPTION defining the soil resistance supporting the pile. The test is performed by striking the pile head This is done by matching forces at the pile head with a piling hammer or other suitable drop computed using stress wave theory with those weight whilst monitoring pile soil response in actually measured during the test. The terms of pile head force and velocity using programs output many parameters valuable to specially developed bolt-on reusable the experienced piling engineer. -

Evaluating the Capacity of Helical Piles in Clay Tills Using Pile Load Tests

Evaluating the Capacity of Helical Piles in Clay Tills Using Pile Load Tests Ivanna Montani Stantec Consulting Ltd, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes seven static load tests conducted on helical piles installed in clay till at a site in Northern Manitoba, Canada. Four methods, the Davisson Offset Limit, the Hansen Ultimate Load, the Chin-Kondner Extrapolation, and the Decourt Extrapolation are used to determine the ultimate capacity using the pile load test results. The ultimate capacities obtained were then used to determine the empirical parameter Kt for helical piles in clay tills, this parameter relates the pile capacity of helical piles to the installation torque of the pile. The Davisson Offset Limit and the Hansen Ultimate Load provided consistent and conservative ultimate capacities based on the pile load test results and showed lesser variability in results compared with the Chin-Kondner Extrapolation and Decourt Extrapolation methods. The ultimate loads based from the Hansen and Davisson methods were used to calculate a Kt value. It was determined that a Kt value ranging from 9 m-1 to 11 m-1 is appropriate for evaluating the capacity of a helical pile in clay tills using the installation torque of the pile. RÉSUMÉ Cette thèse fait l’analyse de sept essais de mise en charge statique effectués sur des pieux vissés installés dans une formation de moraine (till) argileuse dans le nord du Manitoba, au Canada. Quatre méthodes ont été utilisées pour la détermination de la capacité ultime utilisant les résultats des essais de mise en charge : la méthode de la charge limite décalée (Davisson), la méthode de la charge ultime (Hansen), ainsi que les méthodes d’extrapolation de Chin-Kondner et de Decourt. -

Downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE)

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR SOIL MECHANICS AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING This paper was downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE). The library is available here: https://www.issmge.org/publications/online-library This is an open-access database that archives thousands of papers published under the Auspices of the ISSMGE and maintained by the Innovation and Development Committee of ISSMGE. Reliability of statnamic load testing of rock socketed end bearing bored piles Fiabilité d’un essai de charge Statnamic sur un pieu résistant à la pointe foré dans de la roche H. S. Thilakasiri Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. ABSTRACT The pile load testing methods could be broadly classified into three categories: static, rapid and dynamic depending on the rate of loading. In this paper, the rapid load testing method referred to as the Statnamic test is discussed. The commonly used analysis method of the statnamic testing referred to as the Unloading Point (UP) method is used successfully for the floating piles but validity of some of the assumptions of the unloading point method to end bearing bored piles is questionable. Due to this problem, other analytical methods such as: Modified Unloading Point (MUP) method, Segmental Unloading Point (SUP) method and other signal matching techniques are introduced by some researches. Therefore, the validity of the unloading point method to rock socketed end bearing bored piles in Sri Lanka is investigated in this paper. This investigation is carried out using the commonly used wave number. Furthermore, the wave equation method, commonly used numerical procedure to model dynamic behavior of piles, is used by the author to investigate the validity of the assumptions associated with the unloading point method to rock socketed end bearing bored piles. -

Analysis of the Pile Load Tests at the Us 68/Ky 80 Bridge Over Kentucky Lake

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Civil Engineering Civil Engineering 2019 ANALYSIS OF THE PILE LOAD TESTS AT THE US 68/KY 80 BRIDGE OVER KENTUCKY LAKE Edward Lawson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.248 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lawson, Edward, "ANALYSIS OF THE PILE LOAD TESTS AT THE US 68/KY 80 BRIDGE OVER KENTUCKY LAKE" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Civil Engineering. 86. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ce_etds/86 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil Engineering at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Civil Engineering by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Dynamic and Static Tests of Prestressed Concrete Girder Bridges in Florida

DYNAMIC AND STATIC TESTS OF PRESTRESSED CONCRETE GIRDER BRIDGES IN FLORIDA BY MOUSSA A. ISSA MOHSEN A. SHAHAWY STRUCTURAL ANALYST CHIEF STRUCTURAL ANALYST STRUCTURAL RESEARCH CENTER, MS 80 FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA 32310 MAY 1993 DYNAMIC AND STATIC TESTS OF PRESTRESSED CONCRETE GIRDER BRIDGES IN FLORIDA by Moussa A. Issa, Ph.D., P.E. Mohsen A. Shahawy, Ph.D., P.E. Structural Analyst Chief Structural Analyst Structural Research Center, MS 80 Florida Department of Transportation, Tallahassee SYNOPSIS The paper presents the results of full scale static and dynamic tests on two prestressed concrete bridges. Both bridges contain a variety of AASHTO type girders and were designed to carry two lanes of HS20 loading. The critical spans were instrumented at quarter span (L/4) and midspan (L/2) with accelerometers, strain gages and deflection transducers. The bridge load testing apparatus consists of a mobile data acquisition system and two load testing vehicles, designed to deliver the ultimate live l o a d specified by the AASHTO Code. For static testing, the bridge w a s incrementally loaded u p to the full ultimate design live load. The test vehicles were loaded to be equivalent to HS-20 truck loads. At each load step the instruments were monitored and the results were compared to the analytical model before proceeding w i t h the next load step. The dynamic load tests were performed with the two testing vehicles traveling at 55 MPH, 45 MPH, and 35 MPH. The results indicated an increase in the strain and deflection amplitudes, with an increase of vehicle speed. -

Soils and Foundations Handbook 2016

Soils and Foundations Handbook 2016 State Materials Office Gainesville, Florida This page is intentionally blank. i Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................ xii List of Tables ............................................................................................................. xiv Chapter 1 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Geotechnical Tasks in Typical Highway Projects.................................................. 1 1.1.1 Planning, Development, and Engineering Phase ...................................... 1 1.1.2 Project Design Phase ................................................................................. 2 1.1.3 Construction Phase .................................................................................... 2 1.1.4 Post-Construction Phase ............................................................................ 2 Chapter 2 2 Subsurface Investigation Procedures ........................................................................ 4 2.1 Review of Project Requirements ..................................................................... 4 2.2 Review of Available Data................................................................................ 4 2.2.1 Topographic Maps.................................................................................... -

Foundation Manual Chapter 8, Static Pile Load Testing and Pile Dynamic

CHAPTER 8 OCTOBER 2015 CHAPTER Static Pile Load Testing and Pile 8 Dynamic Analysis 8-1 Introduction Chapter 1, Foundation Investigations, of this Manual explained how Geotechnical Services performs a foundation investigation for all new structures, widenings, strengthening, or seismic retrofits. Under normal circumstances, the Geoprofessional assigned to perform the investigation is able to gather enough information to recommend a pile type and tip elevation that is capable of supporting the required loads on the recommended pile foundation. However, there are situations where subsurface strata are variable, unproven, or of such poor quality that additional information is needed in order to make solid pile foundation recommendations. In these situations, Static Pile Load Testing and/or Pile Dynamic Analysis (PDA) will be recommended. Information obtained from the testing and/or PDA will be used to verify design assumptions or modify foundation recommendations. Personnel from Geotechnical Services, Foundation Testing Branch, perform Static Load Testing and PDA on Caltrans projects. Once the testing is completed, written reports summarizing the findings are transmitted to the Engineer. Ideally, these tests would be performed in the Design Phase; however, they are often done in the Construction Phase. 8-2 Reasons for Static Load Testing and Pile Dynamic Analysis Static Load Tests measure the response of a pile under an applied load and are the most accurate method for determining pile capacities. They can determine the ultimate failure load of a foundation pile and determine its capacity to support the load without excessive or continuous displacement. The purpose of such tests is to verify that the load capacity in the constructed pile is greater than the nominal resistance (Compression, Tension, Lateral, etc.) used in the design. -

BUILDING CONSTRUCTION 1 ARCH 205 | a Foundation Is a Structure That Transfers Loads to the Ground

BUILDING CONSTRUCTION 1 ARCH 205 | A foundation is a structure that transfers loads to the ground. Foundations are generally broken into two categories: 1. shallow foundations and 2. deep foundations. 2 3 Shallow foundations of a house versus the deep foundations of a Skyscraper 1- SHALLOW FOUNDATIONS Shallow foundations are usually dug a meter or so into suitable soils. One common type is the spread footing which consists of strips or pads of concrete (or other materials) which extend below the frost line and transfer the weight from walls and columns to the soil or bedrock. Another common type is the slab- on-grade foundation where the weight of the building is transferred to the soil through a concrete slab placed at the surface. 4 SHALLOW FOUNDATION 1. A shallow foundation is a type of foundation which transfers building loads to the earth very near the surface, rather than to a subsurface layer or a range of depths as does a deep foundation. 2. Shallow foundations include: 1. spread footing foundations, 2. mat-slab foundations, and 3. slab-on-grade foundations 5 1- SHALLOW FOUNDATIONS SPREAD FOOTING FOUNDATION | Spread footing foundations consists of strips or pads of concrete (or other materials) which transfer the loads from walls and columns to the soil or bedrock. Embedment of spread footings is controlled by several factors, including development of lateral capacity, penetration of soft near-surface layers, and penetration through near-surface layers likely to change volume due to frost heave or expansion and contraction. | These foundations are common in residential construction that includes a basement, and in many small commercial structures. -

High Strain Dynamic Load Testing of Drilled Shafts

Supplemental Technical Specification for High Strain Dynamic Load Testing of Drilled Shafts SCDOT Designation: SC-M-712-2 (07/19) 1.0 GENERAL 1.1 This work shall consist of performing high-strain dynamic testing using a drop weight loading system on a test drilled shaft for the purpose of determining and/or verifying the nominal bearing resistance that may be used in the design of production drilled shafts. In addition, the structural integrity of the test drilled shaft, the load-deflection and soil-load transfer relationships shall also be determined. Production drilled shaft lengths may be adjusted after results of the test drilled shaft have been analyzed. No materials shall be ordered until drilled shaft lengths are approved by the Department. The test shaft depth, diameter, and location shall be as specified in the plans. The testing specified in the project documents shall be conducted in general accordance with ASTM D4945 – Standard Test Method for High-Strain Dynamic Testing of Deep Foundations and this Supplemental Technical Specification. 1.2 The drop weight load testing equipment shall have sufficient capacity to fully mobilize the test shafts’ nominal bearing resistance shown in the plans. 1.3 The location of the test drilled shaft (non-production) shall be as indicated in the plans. The test drilled shaft shall maintain a minimum distance of 25 feet from any foundation element of any future bent. The Contractor shall submit the proposed location to the Department for approval. 1.4 Load testing of the test drilled shaft shall not begin until the concrete has attained a compressive strength (f’c) as indicated in the plans and had a curing time of no less than 7 days.