Pakistan Journal of Languages and Translation Studies Issue-IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in Society: a Cross-Cultural Study of Five Communities in Scotland

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in society: a cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3173/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ENGLISH LANGUAGE, COLLEGE OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Naming in Society A cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland Ellen Sage Bramwell September 2011 © Ellen S. Bramwell 2011 Abstract Personal names are a human universal, but systems of naming vary across cultures. While a person’s name identifies them immediately with a particular cultural background, this aspect of identity is rarely researched in a systematic way. This thesis examines naming patterns as a product of the society in which they are used. Personal names have been studied within separate disciplines, but to date there has been little intersection between them. This study marries approaches from anthropology and linguistic research to provide a more comprehensive approach to name-study. Specifically, this is a cross-cultural study of the naming practices of several diverse communities in Scotland, United Kingdom. -

Curriculum Vitae 1 Akbar Ahmed, Phd Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic

Akbar Ahmed - Curriculum Vitae Akbar Ahmed, PhD Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies School of International Service, American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington DC 20016 Office: (202) 885-1641/1961 Fax: (202) 885-2494 E-Mail: [email protected] Education 2007 Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. 1994 Master of Arts, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 1978 Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, London, UK. 1965 Diploma Education, Selwyn College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (2 Distinctions). 1964 Bachelor of Social Sciences, Honors, Birmingham University, Birmingham, UK (Economics and Sociology). 1961 Bachelor of Arts, Punjab University, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan (Gold Medal: First in History and English). 1957-59 Senior Cambridge (1st Division, 4 Distinctions)/Higher Senior Cambridge (4 'A' levels, 2 Distinctions), Burn Hall, Abbottabad. Professional Career 2012 Diane Middlebrook and Carl Djerassi Visiting Professor, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Michaelmas Term). 2009- Distinguished Visiting Affiliate, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 2008-2009 First Distinguished Chair for Middle East/Islamic Studies, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 2006- Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, Washington DC. 2005-2006 Visiting Fellow at Brookings Institution, Washington DC -- Principal Investigator for “Islam in the Age of Globalization”, a project supported by American University, The Brookings Institution, and The Pew Research Center. 2001- Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies and Professor of International Relations, School of International Service, American University, Washington DC. 1 Akbar Ahmed - Curriculum Vitae 2000-2001 Visiting Professor, Department of Anthropology, and Stewart Fellow of the Humanities Council at Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Pecuniary and Non-Pecuniary Motivations for Tax Compliance: Evidence from Pakistan

Pecuniary and Non-Pecuniary Motivations for Tax Compliance: Evidence from Pakistan Joel Slemrod, Obeid Ur Rehman & Mazhar Waseem UNU-WIDER, Helsinki October 2019 Introduction I Tax evasion is a pervasive problem, especially in developing economies I In the standard tax compliance model evasion is deterred by the threat of fine and penalty (Allingham & Sandmo, 1972) I But evasion may also be deterred by social and psychological factors. Individuals may I feel guilt or shame from evading (Andreoni et al., 1998) I value how they are seen by peers (Luttmer & Singhal, 2014) I have intrinsic motivation to pay taxes (Dwenger et al. 2016) 1 / 62 Introduction I The existence of such non-pecuniary motivations is increasingly being recognized I Yet, limited evidence on I how important they are, and I if governments can prime them for resource mobilization I This paper uses two Pakistani programs to study these questions 2 / 62 First Program – Public Disclosure I The government began revealing income tax liability reported by every taxpayer in the country from 2012 I Two tax directories are published each year; one for MPs and one for all taxpayers I The directories are available online in a searchable PDF format and can be downloaded by anyone I They list the name, tax identifier, and income tax liability of taxpayers I The MPs’ directory also lists their constituency number 3 / 62 First Program – Public Disclosure 4 / 62 Second Program – Privileges & Honor Cards (TPHC) I Acknowledges and honors the top-100 tax paying corporations, partnerships, employees and self-employed I Holders of the Honor Card receive automatic invitation to State Dinners. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing. -

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No. Of Students : 474 SL. No. Roll No. Name of the Student Father's Name Mother's Name 1 19002 AJAY ORAON NIRMAL ORAON PATI DEVI 2 19003 PUJA KUMARI BINOD PARSAD SAHU SUNITA DEVI 3 19004 JYOTSANA KUMARI BINOD KUMAR NAMITA DEVI 4 19005 GAZAL SRIVASTVA BABY SANTOSH KUMAR SRIVASTAVA ASHA SRIVASTVA 5 19006 ANURADHA KUMARI PAPPU KUMAR SAH SANGEETA DEVI 6 19007 SUPRIYA KUMARI DINESH PARSAD GEETA DEVI 7 19008 SUPRIYA KUMARI RANJIT SHINGH KIRAN DEVI 8 19009 JYOTI KUMARI SHANKAR DUBEY RIMA DEVI 9 19010 NIDHI KUMARI PREM KUMAR SAW BABY DEVI 10 19011 SIMA KUMARI PARMOD KUMAR GUPTA SANGEETA DEVI 11 19012 SHREYA SRIVASTAV PRADEEP SHRIVASTAV ANIMA DEVI 12 19013 PIYUSH KUMAR DHANANJAY MEHTA SANGEETA DEVI 13 19014 ANUJ KUMAR UPENDRA VISHWAKARMA SHIMLA DEVI 14 19015 MILAN KUMAR SATYENDRA PRASAD YADAV SHEELA DEVI 15 19016 ABHISHEK KUMAR GUPTA SANT KUMAR GUPTA RINA DEVI 16 19017 PANKAJ KUMAR MUKESH KUMAR SUNITA DEVI 17 19018 AMAN KUMAR LATE. HARISHAKAR SHARMA RINKI KUMARI 18 19019 ATUL RAJ RAJESH KUMAR SATYA RUPA DEVI 19 19020 HARSH KUMAR SHAILENDRA KR. TIWARY SNEHLATA DEVI 20 19021 MUNNA THAKUR HIRA THAKUR BAIJANTI DEVI 21 19022 MD.FARID ANSARI JARAD HUSSAIN ANSARI HUSNE ARA 22 19023 MD. JILANI ANSARI MD.TAUFIQUE ANSARI FARZANA BIBI 23 19024 RISHIKESH KUNAL DAMODAR CHODHARY KAMLA DEVI 24 19025 VISHAL KR. DUBEY RAJEEV KUMAR DUBEY KIRAN DEVI 25 19026 AYUSH RANJAN ANUJ KUMAR DWIVEDI ANJU DWIVEDI 26 19027 AMARTYA PANDEY SATISH KUMAR PANDEY REENA DEVI 27 19028 SHIWANI CHOUHAN JAYPAL SINGH MAMTA DEVI 28 19029 SANDEEP KUMAR MEHTA -

Why Do Skilled Immigrants Struggle in the Labor Market? a Field Experiment with Six Thousand Resumes

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES WHY DO SKILLED IMMIGRANTS STRUGGLE IN THE LABOR MARKET? A FIELD EXPERIMENT WITH SIX THOUSAND RESUMES Philip Oreopoulos Working Paper 15036 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15036 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2009 This research was carried out with support from Metropolis British Columbia. It could not have been completed without the awesome research assistance from Amit Dhand, Wei Gong, Adam Kowalczewski, Chris-Ann Monteiro, Monica Pu, and Ayaz Warraich. I also thank Joana Lahey for providing her program to randomize resume characteristics, and Rishi Aurora for computing service support. I am grateful to Marianne Bertrand Tarek Hussain, Dan-olof Rooth, Katherine Laird, and Joanna Lahey for detailed suggestions, and to seminar participants at the ‘Comings and Goings’ conference at the Ottawa Research Data Center, the 2008 Symposium on Findings from Small Scale Experiments in Ottawa, Simon Fraser University, and the University of British Columbia. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by Philip Oreopoulos. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Why Do Skilled Immigrants Struggle in the Labor Market? A Field Experiment with Six Thousand Resumes Philip Oreopoulos NBER Working Paper No. -

Do Terrorist Attacks Affect Ethnic Discrimination in the Labour Market? Evidence from Two Randomised Field Experiments

Do Terrorist Attacks Affect Ethnic Discrimination in the Labour Market? Evidence from Two Randomised Field Experiments Gunn Elisabeth Birkelund Elisabeth Ugreninov Tak Wing Chan Arnfinn Midtbøen Jon Rogstad Department of Quantitative Social Science Working Paper No. 17-02 January 2017 Disclaimer Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the UCL Institute of Education. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. DoQSS Workings Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. Department of Quantitative Social Science, UCL Institute of Education, University College London, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL, UK Do Terrorist Attacks Affect Ethnic Discrimination in the Labour Market? Evidence from Two Randomised Field Experiments Gunn Elisabeth Birkelund1, Elisabeth Ugreninov2, Tak Wing Chan3, Arnfinn Midtbøen4 and Jon Rogstad5 Abstract Terrorist attacks are known to influence public opinion. But do they also change behaviour? We address this question by comparing the results of two identical randomised field experiments on ethnic discrimination in hiring that we conducted in Oslo. The first experiment was conducted before the 2011 terrorist attacks in Norway; the second experiment was conducted after the attacks. In both experiments, applicants with a typical Pakistani name were significantly less likely to get a job interview compared to those with a typical Norwegian name. But the ethnic gap in call-back rates were very similar in the two experiments. -

Istanbul Fragment in 'Phags-Pa and Old Uyghur Script Revisited1

ISTANBUL FRAGMENT IN ’PHAGS-PA AND OLD UYGHUR SCRIPT REVISITED1 MEHMET ÖLMEZ – ALEXANDER VOVIN İSTANBUL ÜNIVERSITESI – EHESS/CRLAO Abstract This article represents a joint effort of a Turcologist and a Mongolist to present a new interpretation of a bilingual fragment kept in the museum section of the library of the Istanbul University and probably dating from the fifteenth century. This is likely the latest text written in ’Phags-pa Mongolian script and one of the earliest samples of pre-Chagatay Turkic in Old Uyghur script. Résumé Cette article est le fruit de la recherche conjointe d’un turcologue et d’un mongolisant. Elle présente une interprétation nouvelle d’un fragment bilingue conservé au musée de l’Université d’Istanbul et datant probablement du XVe siècle. Ce texte, peut-être le dernier qui fut écrit en alphabet mongol ’Phags-pa, un alphabet mongol, est aussi l’un des premiers exemples de turc pré-Chagatay en écriture vieux ouïghour. An interesting bilingual fragment is kept in the spite of the comprehensive nature of the research by Tuna museum section of the library of the Istanbul University and Bosson (1962), the further improvement of the (F 1423). It is found in the fifteenth century compendium description of the ’Phags-pa script used in the fragment Mecmacu’l-cacāyib ‘Collection of curiosities’ that deals and its reading, as well as of the linguistic analysis, and with various books, samples of calligraphy, and other the translation of the Middle Mongolian text are possible. curiosities (see Plate III for its cover page). This fragment In particular, we believe that obscure places in the Middle is in Middle Mongolian written in the ’Phags-pa script Mongolian text can be clarified on the basis of the pre- and in pre-Chaghatay in Old Uyghur script. -

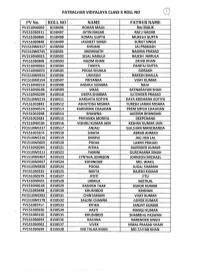

Pvno. ROLL NO NAME FATHER NAME

PATRACHAR VIDYALAYA CLASS X ROLL NO _. PVNo. ROLL NO NAME FATHER... NAME PV1510NOO02 8158496 ROHAN MALIK RAJ MALIK PV151050911 8158497 JATIN NAGAR RAJ:J NAGAR PV1510S0860 8158498 KOMAlGUPTA MUKEStl GUPTA PV1510E0848 8158499 JASI'JlEETSINGH SURJITSINGH PV1510W0317 8158500 SHIVANI JAIPRAKASH PV1510W0745 8158501 SHESHNATH NAGINA PRASAD PV1510N0023 . 8158502 SEJAl NARULA RAJESH NARULA PV1510S0868 81S8503 NA2IM KHAN ZAHID KHAN PV1510N0024 8158504 TANIYA PANHJ GUPTA PV1510N0070 8158505 PooJA SHUKLA GORAKH PV1510W0924 8158506 URVASHI RAKESHBHAlLA PV1510W0194 8158507 PRIYANKA VIJAY KUMAR PV1510N0218 8158508 ANSHUl SUNGRA RAJU PV1510N0106 8158509 VIKAS SATNARAYAN SHAH PV1510N0209 8158510 DEEPASHARMA 5ATENOER- PRASAD PV1510W0219 . 8158511 HARSHITA KOTIYA [lAVA KRISHANA KOTIYA PV1510C0842 8158512 A5HUTD5H MI5HRA ~URE5H SARAN MI5HRA PV1510N0574 8158513 KARISHMA CHAUHAN PREM SIIIIGH- CHAUHAN PV1510C0208 8158514 BHAWNA JAGDISH BHANDARI PV1510C0381 8158515 PRIYANKA MORIYA DEEPCHAND PV1510N0104 8158516 VISHNU KUMAR JAIN KESHAV KUMAR JAIN PV1S10W0237 8158517 ANJALI GULSHAN MANCHAN DA PV1510C03C>8 8158518 SHAFIA ABRARAHMAD PV1510WG216 8158519 DIMPLE JA(o,IISH LAl PV1510W0605· 8158520 POOJA LAXMI PRASAD PV1510N0284 8158521 RITIKA RAJENDERKUMAR PV1510W0211 8158522 YAMINI GURCHARNA SINGH PV1510W0407 8158523 CYNTHIA JOHNSON JOHNSor~ MICHAEL PV1510W0667 8158524 KOHINOOR MD. WAKll PV1510W0858 8158524 POOJA JUGAL SHARMA PV1510S0235 8158525 NIKITA RAJESHKUMAR PV151OS0578 8158527 JYOTI JITU PV1510N0451 8158528 URMILA MOTILAl PV151ON0146 8158529 KA5HI5H TAAK ASHOK -

A Study of the Deobandi Understanding and Practice of Taøawwuf

SHARÔÑAT AND ÙARÔQAT: A STUDY OF THE DEOBANDI UNDERSTANDING AND PRACTICE OF TAØAWWUF BY AAMIR BASHIR INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA 2010 SHARÔÑAT AND ÙARÔQAT: A STUDY OF THE DEOBANDI UNDERSTANDING AND PRACTICE OF TAØAWWUF BY AAMIR BASHIR A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization International Islamic University Malaysia DECEMBER 2010 ABSTRACT DeobandÊs are a reformist Sunni group from South Asia. They are a loosely connected group that shares similar attitudes towards Islam and SharÊÑah (Islamic law). The early DeobandÊ masters who flourished at the end of nineteenth and the beginning of twentieth century combined in themselves high spiritual achievements with scholarly erudition. Since then, DeobandÊ attitudes towards taÎawwuf have evolved and diversified. Various scholars have studied different dimensions of the DeobandÊ movement. However, to date there has been no comprehensive study of the DeobandÊ understanding and practice of taÎawwuf. Through analysis of DeobandÊ works about taÎawwuf, biographies of DeobandÊ masters, and field work amongst contemporary DeobandÊ Sufis, this study investigates DeobandÊ understanding and practice of taÎawwuf, and its relationship with SharÊÑah. This thesis argues that two NaqshbandÊ scholar Sufis, AÍmad SirhindÊ (d. 1624) and ShÉh WalÊ AllÉh (d. 1762), have been most instrumental in shaping DeobandÊ attitudes towards Islam as whole. This NaqshbandÊ scholarship combined with DeobandÊs’ ChishtÊ ØÉbirÊ heritage to create the DeobandÊ school of thought. The two main planks of DeobandÊ Sufi doctrine are tawÍÊd and following the Sunnah. Furthermore, there are two main characteristics of the DeobandÊ approach to taÎawwuf. One, they were keen to avoid those traditional practices, which invited criticism from externalist scholars. -

A Publication of the Institute of Communication and Cultural Studies University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan

Journal of Communication and Cultural Trends (JCCT) Volume No. 1, Issue No. 1, Spring 2019 ISSN(P): 2706-9141 ISSN(E):2706-915X Journal DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jcct Issue DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jcct.11 Homepage: https://journals.umt.edu.pk/index.php/jcct/Home Journal QR Code: Gender Discourse of ‘Equal Opportunity’ for Male and Female in Article: Pakistani English Textbooks: A Critical Discourse Analysis Study Amina Khalid Author(s): Arshad Ali Khan Sayyed Rashid Ali Shah Online Published: Spring 2019 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jcct.11.05 Article QR Code: Khalid, A., Khan, A. A., & Shah, S. R. A. (2019). Gender discourse of ‘Equal opportunity’ for male and female in Pakistani English To Cite Article: textbooks: A critical discourse analysis study. Journal of Communication and Cultural Trends, 1(1), 77–98. Crossref A publication of the Institute of Communication and Cultural Studies University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan. Gender Discourse of ‘Equal Opportunity’ for Male and Female in Pakistani English Textbooks: A Critical Discourse Analysis Study Amina Khalid1* Arshad Ali Khan2 Sayyed Rashid Ali Shah3 Abstract The aim of the present article is to investigate the representation of male and female within the gender discourse of ‘equal opportunity’ in Pakistani English textbooks. The present study has focused on if the gender discourse of ‘equal opportunity’ resisted or supported in Pakistani English textbooks at varied educational levels and in what ways such discourse manifests gender notions in Pakistani society. The paradigm of this research is descriptive and qualitative. The corpus of the study is collected from the English textbooks of 5th, 6th and 8th classes of the Punjab Textbook Board Lahore through purposive sampling.