Cams Tide Mill, Fareham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Lady Betty Delme and Children.—By Sir Joshua Reynolds

LADY BETTY DELME AND CHILDREN.—BY SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS. From the Picture formerly at Cams Hall, Fareham. 99 ON A PORTRAIT OF LADY BETTY DELME, BY . SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS, FORMERLY AT CAMS HALL, FAREHAM, WITH NOTES ON THE FAMILY OF DELME\ BY REV. G. W. MINNS, LL.B..F.S.A. A remarkable picture, perhaps one of the finest works of Reynolds, which for more than a century had adorned the mansion of a family in Hampshire, was, on the death of its owner, the last of his line, put up to auction in London, during the past year, when it realized the unprecedented sum of eleven thousand guineas. Previous to the sale, few persons knew of the existence of this valuable art treasure within the borders of our county, and fewer are perhaps aware that the great artist, and prince of portrait painters, was associated with Hampshire by- family and other personal relations; that he received his baptismal name from his uncle and godfather, the Rev. Joshua Reynolds, a Hampshire clergyman and rector of Stoke Charity, in the churchyard of which parish may still be seen a gravestone with this simple inscription :— J. REYNOLDS, , RECTOR,, . OB. M'DEC, 1734. AET. 66. The memorial consists of a flat stone lying on the ground, between two high tombs, a few yards from the path leading from the gate to the church porch. The parish furnishes no other record of this rector or his family except the entry of his burial on the 27th of December, 1734, five days after his death. -

£ Zr PLAN of HTCHFIELD ABBEY

HANT8 FIELD CLUB, 1896. PLAN OF HTCHFIELD ABBEY £ \t \J,\.J zr THchfidd Abbey 1231 -1S58 A A Ne»& 15 Choir e.. SKur-e> f™, IfiTFloor UmMfercte T3"eaby*I£ry j» DoovWtgr cDJD. TVrmsepK winrChcrode <f BuildindK Exietfho* 1761 - 82 <*~ c« E Cloiater Kh. Cetrder?>*U1 ^ F S»criotfy Cr CJ-tetnfer House H CdilEMUcIor^ (Canon. DanMywfr t.C,H) I Reredarler(?) R.rf«dotry, Tbmbft «y ATobrife SiulSry C?) lOAIlar of S^PfeJer M KaKheavC?) n Allar I?) N Gdlarere? Building Adeem 12 PoeaTian, of Udamay John. dyidonarilcarve 1ft dlebr from DorTer "Rodter a* Ceovdevfer 14 Early dowtvfcy 16 HkABCk^s. «Jcfvn. de CcmJoe 15' Doarwtjy IS" T^rjpervdicuba* Refectory Tiler de. >Vyrilan. William de*lVti]lop Tnnf nf T r T ' ¥ f T x r BT. •.'.•' " •••" . '.« •' •« • •;*.-. .- •- ••: . • - „, • 317 TITCHFIELD ABBEY AND PLACE HOUSE. BY THE REV. G. W. MINNS, LL.B., F.S.A. Titchfield lies between Southampton and Portsmouth, about two'miles from the shores of the Solent, and is the largest civil parish in Hampshire, 17,500 acres in extent. 'Few country towns have a history more varied or of greater interest. The Meonwara occupied the valley which extends from the mouth of the Meon or Titchfield River, two miles below the town, northward as far as East Meon. The discovery of flint weapons and implements shows that the site of Titchfield was occupied long before the Roman invasion, and its river served as a means of, com- munication with the inhabitants of the valley. In Domesday Book Ticefelle, i.e., the manor of Titchfield, is described as a berewick or village belonging to Meonstoke and held by the King, as it had been in the time of Edward the Confessor. -

Hawkins Jillian

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES The significance of the place-name element *funta in the early middle ages. JILLIAN PATRICIA HAWKINS Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2011 UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The significance of the place-name element *funta in the early middle ages. Jillian Patricia Hawkins The Old English place-name element *funta derives from Late Latin fontāna, “spring”, and is found today in 21 place-names in England. It is one of a small group of such Latin-derived elements, which testify to a strand of linguistic continuity between Roman Britain and early Anglo- Saxon England. *funta has never previously been the subject of this type of detailed study. The continued use of the element indicates that it had a special significance in the interaction, during the fifth and sixth centuries, between speakers of British Latin and speakers of Old English, and this study sets out to assess this significance by examining the composition of each name and the area around each *funta site. Any combined element is always Old English. The distribution of the element is in the central part of the south- east lowland region of England. It does not occur in East Anglia, East Kent, west of Warwickshire or mid-Wiltshire or north of Peterborough. Seven of the places whose names contain the element occur singly, the remaining fourteen appearing to lie in groups. The areas where *funta names occur may also have other pre-English names close by. -

Modern City Centre Offices 185.80 to 3202 Sq M (2000 to 33572 Sq Ft to Let

Preliminary Details The Connect Centre Kingston Crescent Portsmouthhughesellard.com Hampshire PO2 8QL Modern City Centre Offices 185.80 to 3202 sq m (2000 to 33572 sq ft To Let Location The Connect Centre is a landmark building located at the foot of the M275 on the northern fringe of Portsmouth City Centre and 1.5 miles from the M27, making the building easily identifiable and • Landmark building accessible to visitors. • 14 car spaces per wing Kingston Crescent provides a polarisation of commerce owing to its excellent accessibility by both • New leases available public and private transport, combined with it being situated equidistant from the motorway and prime shopping area. Transport links and retail facilities nearby provide a strong attraction to a work force. Portsmouth Railway Station is within 1.5 miles by car and the Continental Ferryport is approximately 100 yards away. Commercial Road and Cascades Shopping Precinct are approximately 1 mile to the south. www.hughesellard.com Description The property is 9 storeys with stunning views across Portsmouth. There is a manned reception area with 3 Tenure Leasehold high speed lifts. Terms The office accommodation benefits from comfort cooling and suspended ceilings with recessed lighting. Flexible lease terms available. Accommodation Rent The property has been measured in accordance with the RICS Code of Measuring Practice 6th Edition and £12.00 per sq ft per annum exclusive. has the following net internal floor areas: Legal Costs Both parties to pay their own legal costs. Floor East West Area (Sq Ft) 1st LET TO BDML 2nd LET TO BDML 3rd Let to BDML 4,796 4,796 4th Let to BDML 4,796 4,796 5th LET 4,796 4,796 6th N/A 4,796 4,796 7th N/A 4,796 4,796 8th N/A 4,796 4,796 9th N/A 4,796 4,796 TOTAL 33,572 AVAILABLE Fareham Office 01329 220033 Viewing strictly by prior appointment. -

Hampshire Genealogical Society

The Hampshire Family Now in Historian our 41st year September 2014 Volume 41 No.2 Group of snipers, France, c1916 (page 84) Inside this Issue Local WW1 commemorations • Marriages Legislation & Registration • 30-year-old mystery solved PLUS: Around the groups • Book Reviews • Your Letters • Members Interests • Research Room Journal of the Hampshire Genealogical Society Hampshire Genealogical Society Registered Charity 284744 HGS OFFICE , 52 Northern Road, Cosham, Portsmouth PO6 3DP Telephone: 023 9238 7000 Email: [email protected] Websites: www.hgs-online.org.uk or http://www.hgs-familyhistory.com PRESIDENT Miss Judy Kimber CHAIRMAN PROJECTS Dolina Clarke Eileen Davies, 22 Portobello Grove, Email: [email protected] Portchester, Fareham, Hants PO16 8HU BOOKSTALL Tel: (023) 9237 3925 Chris Pavey Email: Email: [email protected] [email protected] MEMBERS’ INTERESTS SECRETARY Email: [email protected] Mrs Sheila Brine 25 Willowside, Lovedean, WEBMASTER Waterlooville, Hants PO8 9AQ John Collyer, Tel: ( 023) 9257 0642 Email: [email protected] Email: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AND TRUSTEES: [email protected] Sheila Brine TREASURER Dolina Clarke Ann-Marie Shearer Eileen Davies 64 Sovereign Crescent Gwen Newland Fareham, Chris Pavey Hants PO14 4LU Lin Penny Email: Paul Pinhorne [email protected] Ann-Marie Shearer Ken Smallbone MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Keith Turner Gwen Newland Angela Winteridge 52 Northern Road, Cosham, GROUP ORGANISERS – See Group Reports Pages Portsmouth PO6 3DP Tel: (023) 9238 7000 Email: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATES: ALL MEMBERS £15 EDITOR Members may now pay by Credit Card Ken Smallbone at our website. -

Members' Directory 2019-2020

Directory Sponsor MEMBERS’ DIRECTORY RenewableUK 2019-2020 Members’ Directory 2019-2020 Members’ Directory Micro Grid Renewables Generation Solar Electricity Trading Transmission Distribution Demand-Side Centralised Power Response Generation Smart Storage Cities Wind Smart Homes User Demand EVs 25 EUR million Sales in more than Established 6 manufacturing State of the art average annual investments facilities (last 3 years) 50 countries 1950 plants in 3 countries Who we are Tracing its industrial roots back to 1950, Cablel® Hellenic Cables has evolved into a leading European provider of reliable and competitive cable solutions. With 6 manufacturing plants across 3 countries, Cablel® Hellenic Cables covers a wide range of cable products and solutions, from Land and Submarine Power cables to Fiber Optics, Telecommunication cables and Magnet Wires. Cablel® Hellenic Cables offers a wide range of integrated solutions, including design, manufacturing, planning, project management and installation. In-house R&D and testing facilities guarantee continuous product development and innovation. As the world’s need for sustainable and reliable flow of energy and information continues to increase, we remain focused on our mission to provide top-quality products and services meeting the highest technical and sustainability standards set by our customers. HEAD OFFICE: 33, Amaroussiou - Halandriou Str., 151 25 Maroussi, Athens, GREECE Tel.: +30 210 6787 416, +30 210 6787 900, Fax: +30 210 6787 406 [email protected] www.cablel.com 09-13-2019_KX_CABLEL_168x240mm_FINAL.indd -

For Sale Key Features

THE ORCHARD, CAMS HALL ESTATE, FAREHAM, HAMPSHIRE RARE OPPORTUNITY TO OWN A DEVELOPMENT SITE IN A UNIQUE SETTING WITH EXCELLENT ACCESS FOR SALE KEY FEATURES • Established business park • Unique new build • Tranquil setting • Excellent transport links • On site, café restaurant and golf course • Impressive views • Fareham Tech hub 1 acre development site suitable for offices/Hi-tech buildings T: 023 8082 0900 vailwilliams.com THE ORCHARD, CAMS HALL ESTATE, FAREHAM, HAMPSHIRE LOCATION The Orchard is located in the heart of the Cams Estate bordering the award winning golf course and the historic walled garden. The office campus is set in a tranquil setting with mature grounds of the former Cams Hall – now a business centre. Portsmouth Harbour and Fareham Creek wrap around the scheme providing pleasant waterside walks and impressing views close to the heart of Fareham. The scheme has a Café onsite serving hot and cold food. Other business located at Cams Hall Estate include Glanvilles Solicitors, Wilkins Kennedy Accountants, Dream Doors HQ. T: 023 8082 0900 vailwilliams.com THE ORCHARD, CAMS HALL ESTATE, FAREHAM, HAMPSHIRE DESCRIPTION The plot itself is a level serviced site surrounded by mature trees bordering the golf course, of approximately 1 acre. TERMS 125 year lease is available at a peppercorn rent. The lease permits B1 planning uses. PLANNING The property falls within the employment zone in the local plan but a full planning application will be required for any proposed development. PRICE Guide price £800,000 exclusive subject to planning. T: 023 8082 0900 vailwilliams.com THE ORCHARD, CAMS HALL ESTATE, FAREHAM, HAMPSHIRE SERVICES The client advises electrical and effluent services are available with water a short distance away, Vail Williams LLP has not checked and does not accept responsibility for any of the services within this property and would suggest that any in-going tenant or occupier satisfies themselves in this regard. -

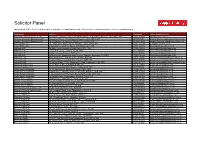

Solicitor Panel

Solicitor Panel Last updated 19/02/2021 (The active panel is available in our application portal. This list may not be representative of the current active panel.) Firm Name Address Telephone Office Email Address Advantage Property Lawyers Ltd Advantage Property Lawyers Ltd, Hurley House, 1 Dewsbury Road, Leeds, LS11 5DQ 0113 2207400 [email protected] Amphlett Lissimore Bagshaws LLP Greystoke House, 80-86 Westow Street, London, SE19 3AF 02087715254 [email protected] Amphlett Lissimore Bagshaws LLP 19-23 Masons Hill, Bromley, Bromley, Kent, BR2 9HD 020 8466 8998 [email protected] Angel Wilkins Llp The White Barn, Manor Road, Wantage, Oxon, OX12 8NE 01235 775 100 [email protected] Angel Wilkins Llp Angel Wilkins, 26 Wood Street, SWINDON, SN1 4AB 01793 427780 [email protected] Ashfords LLP Ashford House Grenadier Road, Exeter, EX1 3LH 01392 337000 [email protected] Ashfords LLP 1 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4A 1AN 0207 5442424 [email protected] Ashfords LLP Gotham House, Tiverton, EX16 6LT 01884 203002 [email protected] Ashfords LLP Ashford Court, Blackbrook Park Avenue, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 2PX 01823 232300 [email protected] Ashtons Legal Waterfront House, Wherry Quay, Ipswich, IP4 1AS 01473 232425 [email protected] Ashtons Legal Trafalgar House, Meridian Way, Norwich, NR7 0TA 01603 703070 [email protected] Ashtons Legal Chequers House, 77-81, Newmarket Road, Cambridge, CB5 8EU 01223 363111 [email protected] -

Cams Hall, Cams Hill, Fareham, Hampshire

Cams Hall, Cams Hill, Fareham, Hampshire View this office online at: https://www.newofficeeurope.com/details/serviced-offices-cams-hall-hill-fareh am-hampshire A selection of traditional offices are available within this delightful Georgian building that overlooks Portsmouth Harbour. The building benefits from ample on-site parking and is located adjacent to a very popular business park. The offices themselves are available on a fully furnished basis with access to meeting and conference rooms as required. Transport links Nearest road: Nearest airport: Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Administrative support AV equipment Car parking spaces Close to railway station Conference rooms Conference rooms High-speed internet High-speed internet (dedicated) Meeting rooms Period building Reception staff Security system Telephone answering service Unbranded offices Video conference facilities Location Set within an expanse of parkland, this business centre occupies a position in a quiet area that has excellent transport links and plenty of amenities nearby. There are a number of leisure facilities in the immediate vicinity, and Fareham town centre is not far away, where tenants can take advantage of an array of useful amenities. Junction 11 of the M27 is a few minutes' drive from the area, offering excellent connections to nearby towns and cities. Southampton Airport can be reached in less than 20 minutes by car. Points of interest within 1000 metres Cams Hall Estate Golf Course (golf course) - 300m from business centre Cams Hill -

All Approved Premises

All Approved Premises Local Authority Name District Name and Telephone Number Name Address Telephone BARKING AND DAGENHAM BARKING AND DAGENHAM 0208 227 3666 EASTBURY MANOR HOUSE EASTBURY SQUARE, BARKING, 1G11 9SN 0208 227 3666 THE CITY PAVILION COLLIER ROW ROAD, COLLIER ROW, ROMFORD, RM5 2BH 020 8924 4000 WOODLANDS WOODLAND HOUSE, RAINHAM ROAD NORTH, DAGENHAM 0208 270 4744 ESSEX, RM10 7ER BARNET BARNET 020 8346 7812 AVENUE HOUSE 17 EAST END ROAD, FINCHLEY, N3 3QP 020 8346 7812 CAVENDISH BANQUETING SUITE THE HYDE, EDGWARE ROAD, COLINDALE, NW9 5AE 0208 205 5012 CLAYTON CROWN HOTEL 142-152 CRICKLEWOOD BROADWAY, CRICKLEWOOD 020 8452 4175 LONDON, NW2 3ED FINCHLEY GOLF CLUB NETHER COURT, FRITH LANE, MILL HILL, NW7 1PU 020 8346 5086 HENDON HALL HOTEL ASHLEY LANE, HENDON, NW4 1HF 0208 203 3341 HENDON TOWN HALL THE BURROUGHS, HENDON, NW4 4BG 020 83592000 PALM HOTEL 64-76 HENDON WAY, LONDON, NW2 2NL 020 8455 5220 THE ADAM AND EVE THE RIDGEWAY, MILL HILL, LONDON, NW7 1RL 020 8959 1553 THE HAVEN BISTRO AND BAR 1363 HIGH ROAD, WHETSTONE, N20 9LN 020 8445 7419 THE MILL HILL COUNTRY CLUB BURTONHOLE LANE, NW7 1AS 02085889651 THE QUADRANGLE MIDDLESEX UNIVERSITY, HENDON CAMPUS, HENDON 020 8359 2000 NW4 4BT BARNSLEY BARNSLEY 01226 309955 ARDSLEY HOUSE HOTEL DONCASTER ROAD, ARDSLEY, BARNSLEY, S71 5EH 01226 309955 BARNSLEY FOOTBALL CLUB GROVE STREET, BARNSLEY, S71 1ET 01226 211 555 BOCCELLI`S 81 GRANGE LANE, BARNSLEY, S71 5QF 01226 891297 BURNTWOOD COURT HOTEL COMMON ROAD, BRIERLEY, BARNSLEY, S72 9ET 01226 711123 CANNON HALL MUSEUM BARKHOUSE LANE, CAWTHORNE,