PADAM and JAVALI MODULE 1 Padam, Atreasure Trove for Abhinaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

New Technology in Multi-Sensory Public

MULTI-SENSORY SITES OF EXPERIENCE: PUBLIC ART PRACTICE IN A SECULAR SOCIETY SUBMITTED IN FULL FULFILLMENT REQUIRED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF THE CONSTRUCTED ENVIRONMENT SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN RMIT UNIVERSITY Anton Glenn Hasell B. Ec, Dip. Ed, B.F.A, P-G Dip F.A, M.F.A September 2002 1 Abstract Western secular societies have come to celebrate the individual within his or her community. Secular society has been shaped to fit the maximum freedoms and rights that are compatible within the compromise that communal life impose upon its members. Earlier communities in both Europe and Asia were bounded by religious practices that privileged the communal perspective over that of the individual. Rituals brought people together and the places in which these rituals were enacted, the temples and cathedrals so central to communal life, were places of complex and powerful multi-sensory experience. It is within such stimulating experience that people recognize themselves as vibrant parts to a greater whole. Artists who work in public-space commissioned works, such as myself, are repeatedly invited to create works of art that signify and celebrate the forms and images that bring the community together. Such communal-building work attempts to countervail the drive to ever greater individual freedoms in secular society. Artists are placed in a difficult position. The most recent developments in computer technology have been used to re-invent the bell. The reinvented bell has become a fundamental element in new bell-sculpture installation works. This thesis develops a context for the use of bells in contemporary public-space design. -

Quoted from Wikipedia.Com, November 2010

Quoted from Wikipedia.com, November 2010 Singing bowls (also known as Himalayan bowls, rin gongs, medicine bowls, Tibetan bowls or suzu gongs in Japan) are a type of bell, specifically classified as a standing bell. Rather than hanging inverted or attached to a handle, standing bells sit with the bottom surface resting. The sides and rim of singing bowls vibrate to produce sound. Singing bowls were traditionally used throughout Asia as part of Bön and Tantric Buddhist sadhana. Today they are employed worldwide both within and without these spiritual traditions, for meditation, trance-induction, relaxation, healthcare, personal well-being and religious practice. Singing bowls were historically made in Tibet, Nepal, India,[1] Bhutan, China, Japan and Korea.[citation needed] Today they are made in Nepal, India, Japan and Korea. The best known type are from the Himalayan region and are often termed Tibetan singing bowls. Origins, history and usage In Buddhist practice, singing bowls are used as a support for meditation,[2] trance induction and prayer. For example, Chinese Buddhists use the singing bowl to accompany the wooden fish during chanting, striking it when a particular phrase in a sutra, mantra or hymn is sung. In Japan and Vietnam, singing bowls are similarly used during chanting and may also mark the passage of time or signal a change in activity. As Perry[3] (1996) and Jansen[4] (1992) state, little is known in western scholarship regarding Himalayan singing bowls. It is likely they were used in rituals, having a specific function like other instruments (such as the ghanta, tingsha, and shang). -

Prapatti an Article by Sri Karalappakam Anantha Padhmanabhan

Page 1 of 10 Prapatti An article by Sri Karalappakam Anantha Padhmanabhan Sriman nArAyaNA out of His great compassion towards the baddha jIvAtmAs propagates vedAs and allied sAstrAs, which are the only way through which they can possibly know about Him & the ways to reach Him. The ultimate and final essence of sAstrAs is that Sriman NArAyaNA is the sarIrI and, all chit & achit are His sarIrA. This eternal sarIra sarIrI bhAvA is composed of the following three things: 1. AdheyatvA (i.e. being supported by a sarIrI): Existence of the sarIrA(body) is due to the sarIrI i.e. sarIrI supports the sarIrA. In other words, if sarIrI ceases to exist, sarIrA also ceases to exist. 2. niyamyatvA (i.e. being controlled by a sarIrI): Not only that sarIrA derives its existence from a sarIrI, it is also being controlled by the sarIrI. So, sarIrA acts as per the will/desires of sarIrI. 3. seshatvA (i.e. existing for the pleasure of sarIrI): Not only that sarIrA is supported & controlled by sarIrI, it exists only for the pleasure of sarIrI, i.e. sarIrI is sarIrA's Master. It is to be noted that the "sarIrI" needn't be physically present inside a "sarIrA". This is not a condition to be met out for the sarIra-sarIrI bhAvA to hold good. Thus Sriman NArAyaNA supports and controls all jIvAtmAs, and all the jIvAtmAs exist purely for His enjoyment. Thus, the very essential nature (svaroopam) of a jIvAtmA is to perform kainkaryam to Sriman NArAyaNA for His pleasure and performance of any other activity doesn't conform to its nature. -

Esoteric Buddhist Ritual Objects of the Koryŏ Dynasty (936-1392): Vajra

Esoteric BuddhistRitual Objectsof the KoryŏDynasty(936-1392): VajraSceptersand VajraBells NellyGeorgieva-Russ,AcademyofKoreanStudies The EsotericBuddhist tradition,knowninKoreaas milgyo ,or secretteaching,has playedimportant role in the history of KoreanBuddhism.Esoteric cults andpractices relatedtoMahayana Buddhism were supposedly present on the Korean peninsula since the introduction of Buddhism in 372 CE. Sutras with esoteric content, such as the Bhaisajyaguru Sutra, the Saddharmapundarika Sutra, Suvarnaprabhasa Sutra etc.,as well as dharani sutras were widely spreadduring the Three Kingdoms period(300-668CE) 1.Esoteric Buddhism was supportedby the royal court bothinthe UnifiedSilla (668-935) and Kory ŏ (918-1392) periods in connection with hoguk pulgyo (Buddhism as National Protector), its rites called to miraculously protect the nation against foreign invaders. Esoteric Buddhism, more than any other Buddhist school, is concernedwith worldly needs thus establishing a link between Buddhist spirituality and secular powers. Nevertheless, the absence of an established esoteric school paralleling the ZhenyaninChina andShingonin Japan andthe unarticulatedpresence of Esoteric beliefs and practices within such all-pervadingly influential sects as S ŏn or Pure Land Buddhism inKorea has leadtothe marginal positionof this fieldinBuddhist studies,bothinKorea andthe West.At the same time,eventhe scarce data onearly KoreanBuddhism reveals its profound influenceduringtheSillaandKory ŏdynasties. Animportantfactor in the practice ofesoteric Buddhism during the Koryŏis the probable existence of two esoteric sects: the Sinin (Mudra) school and the Ch’ongji (Dhārani) school. Both denominations are first encountered in Samguk Yusa ,according to whichthe founding of the Ch’ongji school is associated with the Silla monk Hyet’ŏng. 2 Nevertheless, the main reliable historical data about this school is a number of records in Koryŏ-sa referring tothe twelve century and later,about temples belonging to the Ch’ongji sect where esoteric rituals were conducted. -

Handicraft Survey Report Bell-Metal Products, Part-XD, Series-16, Orissa

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 16 ORISSA PART-XD HANDICRAFT SURVEY REPORT BELL - METAL PRODUCTS S. K. SWAIN Deputy Director of Census Operations, Orissa. CONTENTS Pages FOREWORD V PREFACE VII ACKNOWLEDGEMENT IX CHAPTER - I History of origin and development of the craft - introduction - antiquity 1 - 11 of non-ferrous metals - myths and legends associated with the craft - rise and fall in the growth of the craft during different periods - history of origin and development of metal craft in Orissa - importance of non - ferrous metals - versatility of alloys: brass and bellmetal - names of important craft centres in the state - names of important craft centres outside the state - particulars of community/caste/tribe associated with the craft - number of households engaged in the craft in the state - different handicraft objects produced at different centres - different agencies associated in the development of the craft - bell-metal artisans and Co-operative societies - Kantilo - Nilamadhab Bell-metal and Brass workers Co-operative Society - Mahabir Brass and Bell-metal Co-operative Society - Bapuji Utensils Industrial Co-operative Society - Village Bhatimunda - Jadua non-ferrous Metal Industrial Co-operative Society Pratap Sasan (Balakati) Training-cum-Production Centres associated with the Craft - Brass and Bell-metal Training-cum-Production Centre, Balakati - Brass and Bell-metal Training-cum-common service facilities centre, Kantilo. CHAPTER - II Craftsmen in their rural setting- general particulars of town/villages 13 - 41 selected for -

Disclosure Information

Disclosure of Financial Relationships with Commercial Interests Disclosure Policy Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education (CME) for physicians. BCM is committed to sponsoring CME activities that are scientifically based, accurate, current, and objectively presented. In accordance with the ACCME Standards for Commercial Support, BCM has implemented a mechanism requiring everyone in a position to control the content of an educational activity (i.e., directors, planning committee members, faculty) to disclose any relevant financial relationships with commercial interests (drug/device companies) and manage/resolve any conflicts of interest prior to the activity. Individuals must disclose to participants the existence or non-existence of financial relationships: 1) at the time of the activity or within 12 months prior; and 2) of their spouses/partners. In addition, BCM has requested activity faculty/presenters to disclose to participants any unlabeled use or investigational use of pharmaceutical/device products; to use scientific or generic names (not trade names) in referring to products; and, if necessary to use a trade name, to use the names of similar products or those within a class. Faculty/presenters have also been requested to adhere to the ACCME’s validation of clinical content statements. BCM does not view the existence of financial relationships with commercial interests as implying bias or decreasing the value of a presentation. It is up to participants to determine whether the relationships influence the activity faculty with regard to exposition or conclusions. If at any time during this activity you feel that there has been commercial/promotional bias, notify the Activity Director or Activity Coordinator. -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

XIX WORLD CARILLON CONGRESS Congress: Barcelona, 1 - 5 July Post-Congress: Tarragona, Lleida’S Lands and Montserrat, 6 - 8 July

XIX WORLD CARILLON CONGRESS Congress: Barcelona, 1 - 5 July Post-Congress: Tarragona, Lleida’s Lands and Montserrat, 6 - 8 July As president of Catalonia, it is my pleasure to welcome you to the XIX World Carillon Congress 2017 held in Barcelona at the Palau de la Generalitat, the seat of the Catalan government that I preside. I am convinced that the historical background of the Palau de la Generalitat and its magnificent carillon will give an excellent platform to this congress for enjoying the incomparable sound of the carillon and to delve into the music and the culture that surrounds the carillon in general. We are a small country of only seven and a half million people, but with great strengths in fields such as culture, research and innovation, knowledge, talent, entrepreneurship and economic development. We believe to have a potential equal to that of the advanced countries of Europe, which makes us attractive in the eyes of the world. We are also a country open and welcoming. And we want to share with you our values, our virtues, our desires, our way of life and our understanding to the world. I wish you a very good congress and hope you enjoy our country. We will do our best to make you feel at home! Carles Puigdemont i Casamajó President of the Generalitat de Catalunya The Confraria de Campaners i Carillonistes de Catalunya welcomes you to this congress, that we have prepared with great enthusiasm, in the hope that you will all enjoy the variety of the congress program. From July 1 to July 5, Barcelona will host the congress and from July 6 to July 8 the post-congress will take us for a discovery of the city of Tarragona, the region of Lleida and the monastery of Montserrat. -

Music and the Child

Music and the Child Natalie Sarrazin Open SUNY Textbooks 2016 © 2016 Natalie Sarrazin ISBN: 978-1-942341-20-8 Unless otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. • ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must dis- tribute your contributions under the same license as the original. This publication was made possible by a SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG). IITG is a competitive grants program open to SUNY faculty and support staff across all disciplines. IITG encourages development of innovations that meet the Power of SUNY’s transformative vision. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library (IITG PI) State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 About the Book Children are inherently musical. They respond to music and learn through music. Music expresses children’s identity and heritage, teaches them to belong to a culture, and develops their cognitive well-being and inner self worth. As professional instructors, childcare workers, or students looking forward to a career working with children, we should con- tinuously search for ways to tap into children’s natural reservoir of enthusiasm for singing, moving and experimenting with instruments. -

Fine Chinese Art ᷕ 喅埻普䍵

AUCTION DECEMBER 8TH 2018 Fine Chinese Art ᷕ⚳喅埻普䍵 Japanese and Buddhist Art 㖍㛔⍲ἃ㔁喅埻 FRONT COVER LOT 153 A PORCELAIN FIGURE OF LI TIEGUAI BY ZENG LONGSHENG BACK COVER LOT 223 AN IMPORTANT MUROMACHI PERIOD WOOD FIGURE OF AIZEN MYO-O AUCTION Fine Chinese Art ᷕ⚳喅埻普䍵 Japanese and Buddhist Art 㖍㛔⍲ἃ㔁喅埻 Saturday December 8th 2018 at 1pm CET CATALOG CA1218 VIEWING www.zacke.at IN OUR GALLERY December 3rd – December 8th Monday – Friday 10 AM – 6 PM Saturday December 8th 10 AM – 12.30 PM and by appointment GALERIE ZACKE MARIAHILFERSTRASSE 112 LOT 71 A LARGE AND IMPORTANT 1070 VIENNA AUSTRIA 14TH CENTURY LIMESTONE STELE OF A DEVI Tel +43 1 532 04 52 Fax +20 E-mail offi[email protected] 1 IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABSENTEE BIDDING FORM (According to the general terms and conditions of business Gallery Zacke Vienna) FOR THE AUCTION FINE CHINESE ART JAPANESE AND BUDDHIST ART - CA1218 ON DATE Saturday December 8th 2018 at 1pm CET NO. TITLE BID IN EURO Endangered Species / CITES Information Some items in this catalogue may consist of material such as for example ivory, rhinoceros horn, tortoise shell, coral or any rare types of tropical wood, and are therefore subject to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora [CITES]. Such items may only be exported outside the European Union after an export permit in accordance with CITES has been granted by the Austrian authorities. Zacke Gallery cannot and does not guarantee that such export permit may or will be obtained, but will by order of the winning bidder, once and exclusively after the item in question has been paid in full, apply to obtain such a permit at a fixed administrative fee of euro 500, - per application. -

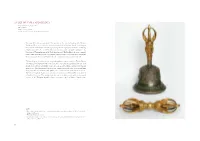

28. Set of Vajra and Ghanta

28. SET OF VAJRA AND GHANTA Copper and mercury gilt copper alloy Tibeto-Chinese Ming, ca. mid-15th century Length (vajra): 17.8 cm (7 in.), height (bell): 23 cm (9.05 in.) The vajra (Tib. rDo rje) and ghanta (Tib. dril bu) are the essential implements of Tantric Buddhism. When a vajra is used in conjunction with a bell (of which the handle is a half-vajra) the pair symbolizes duality: the vajra representing the active principle, the means of attaining enlightenment (thus the actual Buddha manifestation), while the ghanta symbolizes the Perfection of Wisdom, known as the Void (Skt. shunyata).1 For Buddhists the active principle is male, while wisdom is regarded as feminine.2 On depictions of Vajrayana deities displaying these implements, the vajra is usually held in the right hand and the ghanta in the left. This matching set of a vajra with its corresponding ghanta is a good example of Tibeto-Chinese ritual objects that display the style of the early 15th century, but were probably produced a few decades later. There is considerable wear to most areas of the gilding resulting from long and intensive use. The iconography of the five-pointed vajra corresponds to that seen on early Ming examples and the basic structure of the ghanta can be compared to other bells of that same period.3 The body of this ghanta displays a more schematic decoration such as Dharma Wheels, the symbols of Buddha Vairochana. The handle shows the face of this deity, which resides in the central position of the Tathagata mandala, shown wearing an eight-leaf diadem-shaped crown.