Spracklen, K and Henderson, S (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Do Morris Dancers Wear White? Chloe Metcalfe Pp

THE HISTORIES OF THE MORRIS IN BRITAIN Papers from a conference held at Cecil Sharp House, London, 25 - 26 March 2017, organized in partnership by Historical Dance Society with English Folk Dance and Song Society and The Morris Ring, The Morris Federation and Open Morris. Edited by Michael Heaney Why do Morris Dancers Wear White? Chloe Metcalfe pp. 315-329 English Folk Dance and Song Society & Historical Dance Society London 2018 ii English Folk Dance and Song Society Cecil Sharp House 2 Regent's Park Road London NW1 7AY Historical Dance Society 3 & 5 King Street Brighouse West Yorkshire HD6 1NX Copyright © 2018 the contributors and the publishers ISBN 978-0-85418-218-3 (EFDSS) ISBN 978-0-9540988-3-4 (HDS) Website for this book: www.vwml.org/hom Cover picture: Smith, W.A., ca. 1908. The Ilmington morris dancers [photograph]. Photograph collection, acc. 465. London: Vaughan Wil- liams Memorial Library. iii Contents Introduction 1 The History of History John Forrest How to Read The History of Morris Dancing 7 Morris at Court Anne Daye Morris and Masque at the Jacobean Court 19 Jennifer Thorp Rank Outsider or Outsider of Rank: Mr Isaac’s Dance ‘The Morris’ 33 The Morris Dark Ages Jameson Wooders ‘Time to Ring some Changes’: Bell Ringing and the Decline of 47 Morris Dancing in the Earlier Eighteenth Century Michael Heaney Morris Dancers in the Political and Civic Process 73 Peter Bearon Coconut Dances in Lancashire, Mallorca, Provence and on the 87 Nineteenth-century Stage iv The Early Revival Katie Palmer Heathman ‘I Ring for the General -

Playing Music for Morris Dancing

Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Last updated: June 28, 2009 This document was featured in the December 2008 issue of the American Morris Newsletter. Copyright c 2008–2009 Jeff Bigler. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. This document may be downloaded via the internet from the address: http://www.jeffbigler.org/morris-music.pdf Contents Morris Music: A Brief History 1 Stepping into the Role of Morris Musician 2 Instruments 2 Percussion....................................... 3 What the Dancers Need 4 How the Dancers Respond 4 Tempo 5 StayingWiththeDancers .............................. 6 CuesthatAffectTempo ............................... 7 WhentheDancersareRushing . .. .. 7 WhentheDancersareDragging. 8 Transitions 9 Sticking 10 Style 10 Border......................................... 10 Cotswold ....................................... 11 Capers......................................... 11 Accents ........................................ 12 Modifying Tunes 12 Simplifications 13 Practices 14 Performances 15 Etiquette 16 Conclusions 17 Acknowledgements 17 Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Morris Music: A Brief History Morris dancing is a form of English street performance folk dance. Morris dancing is always (or almost always) performed with live music. This means that musicians are an essential part of any morris team. If you are reading this document, it is probably because you are a musician (or potential musician) for a morris dance team. Good morris musicians are not always easy to find. In the words of Jinky Wells (1868– 1953), the great Bampton dancer and fiddler: . [My grandfather, George Wells] never had no trouble to get the dancers but the trouble was sixty, seventy years ago to get the piper or the fiddler—the musician. -

WINSTER MORRIS DANCERS Printed |

Winster Morris dance in the Derbyshire villages. But we also visit other Morris teams all over England. This is us, dancing the Winster Reel, at Thaxted in Essex WINSTER MORRIS DANCERS Printed | www.figcreative.co.uk In 2012 we danced at the Pentecost Festival in And we were guests of Monterubbiano, our twin village in Italy Abingdon Morris at their ‘Mayor of Ock Street’ We also have links with celebrations Ungstein, a wine-making village near Frankfurt in Germany - this is Eva and Wolfgang And with Onzain, a Lords of Misrule: Frank (the Witch) and John (the King) French village on the banks of the Loire We’ve also danced in Poland, Lithuania, Romania and Denmark “This is it and that is it CONTACT US And this is Morris Dancing, If you like the idea of beer and The piper fell and broke his neck foreign travel and want to dance And said it was a chancer. with us - get in touch with: You don’t know and I don’t know Chris Gillott What fun we had at Brampton, Here we are in front of our home crowd, processing through Call: 01629 650404 With a roasted pig and a cuddled duck Winster on Wakes Day 2013 Email: [email protected] And a pudding in a lantern” WHAT ON EARTH IS MORRIS DANCING? Winster Morris dance No one can be sure of its origins. The earliest references, dating with four traditional from around 1500, are to Royal entertainments. But we know characters - a King, that by 1700 it had become a firmly established part of English Queen, Jester and a life. -

COUNTRY DANCE and SONG 21 March 1991

COUNTRY DANCE AND SONG 21 March 1991 , <2./ I Country Dance and Song Editor: David E. E. Sloane, Ph.D. Managing Editor: Henry Farkas Associate Editor: Nancy Hanssen Assistant Editor: Ellen Cohn Editorial Board Anthony G. Barrand, Ph.D. Fred Breunig Marshall Barron Paul Brown Dillon Bustin Michael Cooney Robert Dalsemer Elizabeth Dreisbach Emily Friedman Jerome Epstein, Ph.D. Kate Van Winkle Keller Christine Helwig Louis Killen David Lindsay Margaret MacArthur Jim Morrison John Ramsay John Pearse Richard Powers Sue A Salmons Ted Sannella Jay Ungar Jeff Warner COUNTRY DANCE AND SONG is published annually; subscription is by membership in the Country Dance and Song Society of America, 17 New South Street, Northampton, Massachusetts, 01060. Articles relating to traditonal dance, song, and music in England and America are welcome. Send three copies, typed, double-spaced, to David Sloane, Editor CD&S, 4 Edgehill Terrace, Hamden, CT 06517. Thanks to the University of New Haven for editorial support of this issue. co COUNTRY DANCE AND SONG, March 1991, Copyright Country Dance and Song Society of America. Cover: Figure 1 for "Morris Dancing and America": frontispiece for 1878 sheet music, reprinted courtesy of the Library of Congress. Country Dance and Song Volume 21 March 1991 CONTENTS Morris Dancing and America Prior to 1913 by Rhett Krause . 1 Dancing on the Eve of Battle: Some Views about Dance during the American Civil War by Allison Thompson . 19 Homemade Entertainment through the Generations by Margaret C. MacArthur ........................... 26 Seymour's Humorous Sketches by Alfred Crowquill .......................... ..... 40 Treasured Gifts, Joyous Times: Genny Shimer Remembered by Christine Helwig . -

Morris Dance)

Practice and Theory in Systems of Education, Volume 8 Number 1 2013 ETHNOGRAPHIC AND MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS ON THE ‘CALUS’ (MORRIS DANCE) © Angela JIREGHIE (University V. Goldis Arad, Arad, Romania) [email protected] © Viorica BANCIU (University of Oradea, Oradea, Romania) © Rodica Teodora BIRI Ş (University V. Goldis Arad, Arad, Romania) Received: 13.06.2012; Accepted: 24.04.2013; Published online: 29.05.2013 A very ancient custom formerly spread on the whole Romanian folkloric area, the ‘Calus’ is practiced today in the Danube plane of Oltenia and Muntenia and sporadically in the west and south-west of Transylvania. The ‘Calus’ is a part of the Whitsuntide customs. It is practiced by an esoteric group of 7-9 men, group is constituted in the ‘Saturday of the Whitsuntide’, at half time between Easter and Whitsuntide and which takes a vow. Beginning from this date until Whitsuntide they practice the dances belonging to this custom and become accustomed with their dancing. From Whitsuntide till the Thursday 8 days after it, the group goes from one house to another in its own village or in the neighboring ones and dances the ‘Calus’ dances. The dances which are practiced in our time have some spurs of initiation acts of phallic dances for fecundity and fertility. But their meaning is now blotted in the conscience of the ‘Calusari’ and in that of collectivity where the ‘Calus’ is danced. Not very long ago, were cured by this dance those who were ‘taken from Calus’, from the ’iele’ ( malevolent spirits ) , as they violated the interdiction of not working on some days between the ‘Saturday of the Whitsuntide’ and the Whitsuntide. -

IFLA Publications

THE HISTORIES OF THE MORRIS IN BRITAIN Papers from a conference held at Cecil Sharp House, London, 25 - 26 March 2017, organized in partnership by Historical Dance Society with English Folk Dance and Song Society and The Morris Ring, The Morris Federation and Open Morris. Edited by Michael Heaney What to Dance? What to Wear? The Repertoire and Costume of Morris Women in the 1970s Sally Wearing pp. 267-277 English Folk Dance and Song Society & Historical Dance Society London 2018 ii English Folk Dance and Song Society Cecil Sharp House 2 Regent's Park Road London NW1 7AY Historical Dance Society 3 & 5 King Street Brighouse West Yorkshire HD6 1NX Copyright © 2018 the contributors and the publishers ISBN 978-0-85418-218-3 (EFDSS) ISBN 978-0-9540988-3-4 (HDS) Website for this book: www.vwml.org/hom Cover picture: Smith, W.A., ca. 1908. The Ilmington morris dancers [photograph]. Photograph collection, acc. 465. London: Vaughan Wil- liams Memorial Library. iii Contents Introduction 1 The History of History John Forrest How to Read The History of Morris Dancing 7 Morris at Court Anne Daye Morris and Masque at the Jacobean Court 19 Jennifer Thorp Rank Outsider or Outsider of Rank: Mr Isaac’s Dance ‘The Morris’ 33 The Morris Dark Ages Jameson Wooders ‘Time to Ring some Changes’: Bell Ringing and the Decline of 47 Morris Dancing in the Earlier Eighteenth Century Michael Heaney Morris Dancers in the Political and Civic Process 73 Peter Bearon Coconut Dances in Lancashire, Mallorca, Provence and on the 87 Nineteenth-century Stage iv The Early Revival -

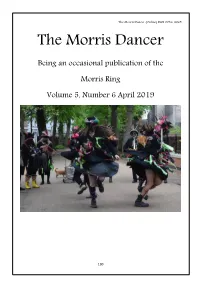

The Morris Dancer (Online) ISSN 2056-8045 the Morris Dancer

The Morris Dancer (Online) ISSN 2056-8045 The Morris Dancer Being an occasional publication of the Morris Ring Volume 5, Number 6 April 2019 130 THE MORRIS DANCER Edited, on behalf of the Morris Ring, by Mac McCoig MA 07939 084374 [email protected] Volume 5, No. 6 April 2019 Contents: Editorial Mac McCoig Page 132 Mumming in Europe, Frazer(ism) in Italy, and “Survivals” in Historical Anthropology: a response to Julian Whybra. Alessandro Testa, Ph.D. Page 134 Manchester Morris Men: The Early Years. Keith Ashman Page 143 The Cambridge Morris Men and traditional dancers. John Jenner Page 151 The Travelling Morrice and traditional dancers. John Jenner Page 154 Some thoughts on the origin of the Papa Stour sword dance. Brian Tasker Page 176 An Ahistory of Morris. Julian Whybra Page 179 Book Review: Discordant Comicals – The Hooden Horses of East Kent. George Frampton Page 188 Cover Picture: Beorma Morris. Photo: Birmingham Evening Mail At the 2014 Jigs Instructional, the three Editors agreed to remind readers what sort of material would be accepted for each Ring publication. In the case of The Morris Dancer, it is any article, paper or study which expands our knowledge of the Morris in all its forms. It is better that the text is referenced, so that other researchers may follow up if they wish to do so, but non-referenced writing will be considered. Text and pictures can be forwarded to: Mac McCoig, [email protected] 131 Editorial In January 2017 at the Jockey Morris Plough Tour, a group of outraged British Afro-Caribbean spectators interrupted a performance by Alvechurch Morris, a black-face Border side. -

Attrrs Volume11 Number1 Morris Matters Volume 11, Number 1

I orr1s attrrs Volume11 Number1 Morris Matters Volume 11, Number 1 Editorial Welcome to volume 11 and 1992. A couple of items you may be interested in. The EFDSS commissioned a report on the future of the society in the '90s; it was released in August 1991. Contact Brenda Goodrich at the Society for details. Also published in 1991 were Cecil Sharp's Morris books, all five in one volume, plus an index! I've been asked to publicise the Vaughan Wil Iiams Memorial Library lectures at Cecil Sharp House on Friday evenings at 7.30 (admission free) as follows: 24/1/92 The Ploughboy and the Plough play, by Alun Howkins 14/2/92 Michael Coleman, the legendary Irish Fiddler , by Henry Bradshaw 13/3/92 Social systems of traditional music making (Irish music in the 1950's), by Reg Hall 10/4/92 Darwinism and the Clog dance team, by Chris Metherell Changing topics slightly, as a morris side treasurer, I ' ve had problems recently with the bank deciding, after all these years, to charge commission on our account. How do other teams manage their relatively low-budget finances? Thinking ahead, as I must, copy date for the next issue is the end of April 1992. Enjoy the dancing season! List of c::ori.teri.ts Page The Abram Morris dance (part 2) by Geoff Hughes 2 Thoughts on Morris Jigs by Fiz Markham 6 Humour in the Morris (part 2) by Roy Dommett 10 Morris dancing and Ballet (1) by Jenepher Parry 12 ( 2) by Alan Dilly 13 Creating new dances by Jonathan Hooton 14 Incomplete set; dances for threes by Roy Dommett 17 No such thing as clog Morris by Chas Marshal l 19 Morris Matters is produced by Beth Neil 1, 36 Foxbury Road, Bromley, Kent , BRl 4DQ, with welcome help from Steve Poole, Jill Griffiths and Catrin Hughes . -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} History and the Morris Dance: a Look

HISTORY AND THE MORRIS DANCE: A LOOK AT MORRIS DANCING FROM ITS EARLIEST DAYS UNTIL 1850 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dr. John Cutting | 204 pages | 31 Jan 2010 | Dance Books Ltd | 9781852731083 | English | Hampshire, United Kingdom Modern dance | Britannica Cunningham, who would have turned this year, would sometimes flip a coin to decide the next move, giving his work a nonlinear, collagelike quality. These were ideas simultaneously being explored in visual art, which was engaged in a similar resetting of boundaries as Pop, Minimalism and conceptual art replaced Abstract Expressionism, with which modern dance was closely aligned; for one, both were preoccupied with working on the floor, as in the paintings of Jackson Pollock and the dances of Martha Graham. Postmodernists remained keen on gravity, however. Certain choreographers would come to treat the floor as a dance partner, just as multidisciplinary artists like Ana Mendieta and Bruce Nauman used it in their performance pieces as a site for symbolic regeneration or heady writhing. Forti considered her work as much dance as sculpture, its human performers art objects like any other — but it hardly mattered, since, for this brief and exceptional window, art, dance and music were almost synonymous. The s New York art scene was famously small, and disciplines blended together as a result. In time, though, the moment of equilibrium passed and the community collapsed, reality itself acting as a sort of score. After the last Judson dance concert in , Childs taught elementary school for five years to support herself before returning to the field. Forti lived for a time in Rome, crossing paths with the Arte Povera movement, and Deborah Hay eventually landed in Austin, where she hosted group workshops. -

The Prancing Pony

The Prancing Pony The Official Newsletter of White Horse Morris Issue #17 http://www.whitehorsemorris.org.uk/home/4594741622 16 July 2020 No Prancing for White Horse this week This week White Horse Morris did not dance at The Benett Arms in Semley. BUT the cricket season did start at last. In this, the seventeenth edition of The Prancing Pony, John Wippell gives as clear an answer to the question of “What is Morris Dancing” as anyone could hope for, but came to no serious conclusion. Graham Lever asks a “Was it him?” question about another member of the side who was unavailable for comment as the PP went to press. Depending on circumstances we may be doing some more dancing, possibly in a field or outside a cricket pavilion. It could be our new normal – everyone else has got one!” We won’t be in Shrewton on 22nd either unless we dance on the field illegally. On this day “Moorish dance”. The term entered English via Flemish 1439 Henry VI bans kissing in England in an attempt to mooriske danse. Comparable terms in other languages are stop the spread of The Black Death German Moriskentanz (also from the 15th century), 1661 The first banknotes in Europe were issued by the French morisques, Croatian moreška, and moresco, Bank of Stockholm moresca or morisca in Italy and Spain. The modern 1965 The Mont Blanc Road Tunnel between Italy and spelling Morris-dance first appears in the 17th century. France opened 1969 Apollo 11 was launched from Cape Kennedy, It is unclear why the dance was so named, “unless in Florida bound for the Moon reference to fantastic dancing or costumes”, i.e. -

A History of Cotswold Morris Dancing in the Twentieth Century

“It’s street theatre really!” A history of Cotswold Morris Dancing in the twentieth century. A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of History, University of Essex. M.A.Garland June 2017 ABSTRACT. This study investigates the history of Morris Dancing in the twentieth century through written sources detailing the development of the dance, but more importantly, through the oral testimony of some of those dancers who began their dancing careers after the second world war. Three particular questions were identified, firstly concerning the way in which ancient dance forms are generally linked, perhaps incorrectly, with place; secondly, the way in which the part that women played in the development of the dance has been written out of the popular modern view of the Morris; and finally, the part that Morris Dancing has played in the production of an invented myth of English history and English tradition. These, and further questions raised during the interviews, forced the study to take a wider view of the history of the dance. Looking back towards the earliest records became important because of the apparent changes that have affected Morris Dancing throughout the centuries, a dance form that is assumed to have been firmly established as an unchanging ritual, but in fact, it would seem, has always been prepared to follow whatever alterations have been demanded by society. Looking forward also became important, because as the dance has clearly changed dramatically during its history, interviewees were keen to explore the ways in which the dance could continue to develop. To follow this final area interviews were conducted with a few of those young dancers who are taking the dance forward. -

Dec., Vol. 17 No. 3

M... CD .Q E ::l ~ z I' ~ .- ...., CD I ~ I c: E ...., ::l 0 ta > u ~ 0 /PJa-1 M .- en <n ~ en • .-... CD ~ '- .Q '- E CD ~ (J CD E 0 ~ Q ...I CD -c( .Q ~ Z E CD > z0 /,~I The American Morris Newsletter Page 1 Amerlcan lAo"ls Newsletter is published three times a year in March/April, A SHORT NOTE FROM SALLY AND LOUISE July/August, and November/December. Supplements include the Annua/ Directory ofMorris Sides in North America and the AMN Reprint Series. Subscription rates are $10.00/year or We are looking forward to this new adventure in our lives - getting to $17.00Itwo-year subscription for an individual, or a bulk rate of $8.50/year each for a better know Morris teams the world round, and continuing this fine vehicle for minimum of six copies mailed to the same address. Overseas subscribers add $4 .00. All people interested in English ritual-dance traditions. We want to thank Jim checks should be in USA currency, made payable to, and mailed to: American Morris Brickwedde, Kay Lara Schoenwetter, Steve Parker, and Lori Levin for their vision News/eNer, clo Sally lackman, 10408 Inwood Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20902-3846; and hard work over the last twelve years. 301/649-7144. The newsletter will remain in the same format for now, with articles on Editors of the Newsletter are Sally Lackman and Louise A. Neu. Curt Harpold is current events and history relevant to English ritual-dance traditions in North the Executive Computer Guru. Team News will be coordinated by Martha Hayes.