The World's Best Poetry, Volume 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

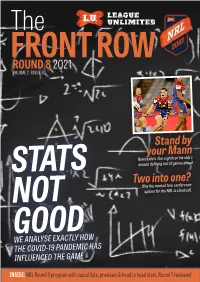

Round 8 2021 Row Volume 2 · Issue 8

The FRONT ROW ROUND 82021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 8 Stand by your Mann Newcastle's five-eighth on his side's STATS season defining run of games ahead Two into one? Why the mooted two-conference NOT system for the NRL is a bad call. GOOD WE ANALYSE EXACTLY HOW THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS INFLUENCED THE GAME INSIDE: NRL Round 8 program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats, Round 7 reviewed LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 8 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 8 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Last week, long-serving former player and referee Henry Feature What's (with) the point(s)? 4-5 Perenara was forced into medical retirement from on-field Feature Kurt Mann 6-7 duties. While former player-turned-official will remain as part of the NRL Bunker operations, a heart condition means he'll be Opinion Why the conference idea is bad 8-9 doing so without a whistle or flag. All of us at LeagueUnlimited. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders. Player Birthdays 10 com wish Henry all the best - see Pg 33 for more from the PRLMO. GAME DAY · NRL Round 8 11-27 Meanwhile - the game rolls on. We no longer have a winless team LU Team Tips 11 with Canterbury getting up over Cronulla on Saturday, while THU Canberra v South Sydney 12-13 Penrith remain the high-flyers, unbeaten through seven rounds. -

Tarsha Gale, Harrold Matthews and SG Ball 2021 Jersey Presentations Marata Niukore and Maika Sivo

Tarsha Gale, Harrold Matthews and SG Ball 2021 Jersey Presentations Marata Niukore and Maika Sivo On the eve of the Parramatta Eels juniors first game, Eels players Maika Sivo and Marata Niukore presented future stars with their game day jerseys. Sivo presented the 2021 Tarsha Gale team their jerseys in an intimate presentation held at Eels HQ, Kellyville Park. While Niukore presented the Harrold Matthews and SG Ball squad their jerseys. Both players shared some insight into the sacrifices they made to become a professional athlete as well as shared some encouragement and words of wisdom. Eels Coaching director, Joe Grima said that “its great for the young boys and girls to be presented their jerseys by the stars of our game. Its exciting for them and reinforces that we are one club and a development club”. Junior League ‘Come Try’ David Hollis, Waqa Blake and Charbel Tasipale On Thursday 11TH Feb, 3 Eels players attended the Kellyville Park ‘come try’ clinic. With over 30 kids present at the clinic, Charbel, David and Waqa participated in the clinic by assisting the organiser’s in skills and drills. The aim of the 3 week clinic is to allow for your males and females to try Rugby League and encourage them to participate in their local competition. Eels Blitz local Schools 2021 NRL squad The Parramatta Eels held their annual School Blitz on Tuesday 16th February with the Blue & Gold venturing out to over 25 schools in the local Parramatta region spreading some important messages around belonging, respect, inclusiveness, nutrition and how to get involved in rugby league. -

Round 252021

FRONTTHE ROW ROUND 25 2021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 26 Finals bound A Newcastle duo celebrates clearing a path to September footy GAME CHANGERS 'CONTESTED' BOMBS, DOUBLE MOVEMENTS, DROP BALLS... THE RULES THAT REALLY SHOULD CHANGE INSIDE: ROUND 25 PROGRAM - SQUAD LISTS, PREVIEWS & HEAD TO HEAD STATS, R24 REVIEWED LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 26 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 26 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Something always happens when the Roosters and Rabbitohs face off. Just a law of physics really. Plenty of controversy Feature Rule changes 4-5 this week which saw Latrell Mitchell slammed with a 6 week suspension for a reckless high shot on opposing centre Joey News NRL statements 6 Manu. With Mitchell not sent off and the subsequent unravelling of the contest, Roosters coach Trent Robinson unloaded on Feature Knights celebration 7 the officials involved in the match, and himself then hit with a breach notice from the NRL for his post-match comments. QRL Teamlists - ISC R16, Colts R13 8 Henry Perenara was also stood down from Bunker duties for the weekend and subsequently won't be manning the screens this QRL results 9 round either. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders 10 This week we've changed tack a little bit - we've got Rick Edgerton tossing up some ideas for discussion, given the NRL's GAME DAY · NRL Round 25 11-27 recent propensity for controversial rule changes.His ideas are designed to clear up grey areas around aerial contests, double LU Team Tips 11 movements and knock-ons - check them out and let us know THU Canberra v Sydney Roosters 12-13 what you think! FRI Cronulla v Melbourne 14-15 Meanwhile we surge into the final round with plenty still on the line for most clubs. -

Symbol and Mood in Tennyson's Nature Poetry Margery Moore Taylor

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1971 Symbol and mood in Tennyson's nature poetry Margery Moore Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Margery Moore, "Symbol and mood in Tennyson's nature poetry" (1971). Master's Theses. 1335. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1335 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYJYIBOL AND MOOD IN TENNYSON•S NATURE POETRY BY MA1"1GERY MOORE TAYLOR A THESIS SUBI.'IITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS JUNE, 1971 Approved for the Department of English and the Graduate School by: Cha rman of the Department of English c:;Dean ofJ'.� the (JG�e . � School CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I: NATURE AND SYMBOLISM CHAPTER II: NATURE AND MOOD CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to show Tennyson's preoccupation with nature in his poetry, his use of her as a projector of moods and s.ymbolism, the interrelation of landscape with depth of feeling and narrative or even simple picturesqueness. Widely celebrated as the supreme English poet and often called the Victorian Oracle,1 Tenny son may well be considered the best exemplar of the nine teenth century. -

The Scientific Age As Reflected in Tennyson

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1945 The Scientific Age as Reflected inennyson T Rose Francis Joyce Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Joyce, Rose Francis, "The Scientific Age as Reflected inennyson T " (1945). Master's Theses. 232. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/232 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1945 Rose Francis Joyce THE SCIENTIFIC AGE AS REFLECTED IN TENNYSON BY SISTER ROSE FRANCIS JOYCE 0. P. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS F'OR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF' ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY JUNE 1945 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. TENNYSON REFLECTS HIS AGE •••••••• • • • • • 1 II. TEJ:rnYSON AND THE NEW SCIENTIF'IC MOVE:MENT • • • • • 15 III. THE SPIRIT OF MODERN SCIENCE IN TENNYSON • • • • • 43 IV. CONFJ.. ICT OF FAITH AND DOUBT IN TENNYSON • • • • • 65 v. TENNYSON THE MAN • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 93 CF...APTER I TENNYSON REFLECTS HIS AGE This poet of beauty and of a certain magnificent idleness, lived at a time when all men had to wrestle and to decide. Tennyson walked through the lowlands of life, and in them met the common man, took.him by the hand, and showed him the unsuspected loveliness of many a common thing. -

Tennyson As a Representative Victorian Poet

Tennyson as a representative Victorian poet Course: B.A. English Hons. Part I Paper: I (sub-section I), Group A Title of e-content: - Tennyson as a representative Victorian poet e-Content by Dr Rohini Department of English, P.U. Email id: [email protected] Mob: 9708723599 Alfred Lord Tennyson was one of the Early Victorian poets along with Mathew Arnold and Robert Browning. Most of us have heard his famous lines: The old order changeth, yielding place to new And God fulfils himself in many ways, Lest one good custom should corrupt the world (The Passing of Arthur) Life: Tennyson was born at Somersby, Lincolnshire. Tennyson met Arthur Henry Hallam whose death he lamented in the poem ‘In Memoriam’(1850). Hallam was engaged to Tennyson’s sister. When Tennyson’s father died, he left the university without a degree and published Poems, chiefly Lyrical. His poetry is a record of the intellectual and spiritual life of the time. Tennyson was made poet Laureate in 1850. Tennyson’s early work is Mariana. Tennyson’s selected works: Poems, Chiefly Lyrical (1830) The Lady of Shalott and other poems (1832) The Princess : A Medly( 1847) In memoriam A.H.H. (1850) Maud, and Other Poems (1855) The idylls of the king (1842-88) Enoch Arden (1864) Tiresias and other poems(1855) Locksley Hall Sixty Years After (1886) The Lotus- Eaters was inspired by his trip to Spain with his close friend Arthur Hallam. The story of The Lotus- Eaters comes from Homer’s ‘The Odyssey.’ In memoriam A.H.H. is a poem by Tennyson. -

Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Dial

EMPORIA STATE r-i 'ESEARCH -GhL WATE PUBLICATION OF THE KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE, EMPORIA Ralph Waldo Emerson and The Dial: A Study in Literary Criticism Doris Morton 7hetjnporia State Re~earchStudie~ KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE EMPORIA, KANSAS 66801 J A Ralph Waldo Emerson and The Dial: A Study in Literary Criticism Doris Morton *- I- I- VOLUME XVIII DECEMBER, 1969 NUMBER 2 THE EMPORIA STATE RESEARCH STUDIES is published in September, December, March, and June of each year by the Graduate Division of the Kansas State Teachers College, 1200 Commercial St., Emporia, Kansas, 66801. Entered as second-class matter September 16, 1952, at the post office at Em- poria, Kansas, under the act of August 24, 1912. Postage paid at Emporia, Kansas. S)+s, ,-/ / J. r d Ll,! - f> - 2 KANSAS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE EMPORIA, KANSAS JOHN E. VISSER President of the College THE GRADUATE DIVISION TRUMANHAYES, Acting Dean EDITORIAL BOARD WILLIAMH. SEILER,Professor of Social Sciencesand Chairmunof Divisfon CHARLESE. WALTON,Professor of English and Head of Department GREEND. WYRICK,Professor of English Editor of thh Issue: GREEND, WYRICK Papers published in the periodical are written by faculty members of the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia and by either undergraduate or graduate students whose studies are conducted in residence under the supervision of a faculty member of the college. ,,qtcm @a"1* a**@ 432039 2 3 ?9fl2 ytp, "Stabement required by the Act of October, 1962; Section 4389, Title a, United Mates Code, showing Ownership, Management and Circulation." The bporh, Sate Ittseuch Studies is pubLished in September, December, March and June of each year. -

Studies in Tennyson Poems of Tennyson

1920. COPTBIGHT, 1889. 1891. 1892. 1897, 1898. BY CHARLES SCRIBNEB's SONS Published February, 1920 PR. 558% V4 THE 8CRBNER PRESS BY HENRY VAN DYKE The Valley of Vision Fighting for Peace The Unknown Quantity The Ruling Passion The Blue Flower Out-of-Doors in the Holy Land Days Off Little Rivers Fisherman's Luck Poems, Collection in one volume Golden Stars The Red Flower The Grand Canyon, and Other Poems The White Bees, and Other Poems The Builders, and Other Poems Music, and Other Poems The Toiling of Felix, and Other Poems The House of Rimmon Studies in Tennyson Poems of Tennyson CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS STUDIES IN TENNYSON <J / A YOUNG WOMAN OF AN OLD FASHION WHO LOVES ABT NOT ONLY FOE ITS OWN SAKE BUT BECAUSE IT ENNOBLES LIFE WHO READS POETRY NOT TO KILL TIME BUT TO FILL IT WITH BEAUTIFUL THOUGHTS AND WHO STILL BELIEVES IN GOD AND DUTY AND IMMORTAL LOVE I DEDICATE THIS BOOK PREFACE 1 HIS volume is intended to be a companion to my Select Poems of Tennyson. I have put it second in the pair because that is its right place. Criticisms, com^ ments, interpretations, are of comparatively little use until you have read the poetry of which they treat. Like photographs of places that one has not seen, they lack the reviving, realizing touch of remembrance. The book contains a series of essays, written at dif- ferent times, printed separately in different places, and collected, substantially, in a book called The Poetry of Tennyson, which was fortunate enough to find many friends, and has now, I believe, gone out of print. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Raiders Win in NRL Carnage RACING PENRITH Pair Viliame Kikau Already Without Jordan Ra- the Way Into the Season

SUNDAY MAY 5 2019 SPORT 59 Mitchell ROOSTERS 42 in a class TIGERS 12 Manly in ROOSTERS Tries: L Mitchell 3, D Tupou, L Keary, of his own N Butcher, B Cordner Goals: L Mitchell 7 STEVE ZEMEK TIGERS Tries: R Matterson, R Farah Goals: E Marsters 2 LATRELL Mitchell has shak- salute to en off uncertainty about his fu- ture to deliver one of the most- dominant individual performances of the year in the Sydney Roosters’ 42-12 thrashing of the Wests Tigers. All week, Mitchell was dog- Hasler ged by headlines that the club was worried about arch rivals South Sydney going all out for SCOTT BAILEY half, he really stepped up and his signature when he came off that’s what he needed to do.” contract at the end of 2020. DES Hasler hadn’t set out to Manly, close to wooden If he was fazed by the make a point in Manly’s 18-10 spoon favourites before the speculation about his future, win over his former NRL club season such was their form and he didn’t show it as he ran in Canterbury, but he might have roster, have won five of their three tries and set up another anyway. past six matches. two in the seven-tries-to-one In his first dealing with the They also lost five-eighth win last night at the SCG. Bulldogs since reaching an Lachlan Croker to a hamstring The Roosters scored their out-of-court settlement with injury in the win, while prop seventh win on the trot to stay the club, Hasler again showed Addin Fonua-Blake played on in top spot as they eyed off a why he was the perfect fit at with a knee injury but would showdown with Canberra dur- the Sea Eagles. -

Carlile and Tennyson: Relations

CARLILE AND TENNYSON: RELATIONS BETWEEN A PROPHET AND A POET by JOHANNES ALLGAIER B.A., University of British Columbia, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of. the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of . British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly - purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives,. It is understood that copying, or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. JOHANNES ALLGAIER Department of ENGLISH The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada. Date April ^0, 1966 CARLYLE AND TENNYSON: RELATIONS BETWEEN A PROPHET AND A POET ABSTRACT Carlyle was much, more popular and influential in the nineteenth century than he is in the twentieth. Many critics "believe that he exerted an influence over Tennyson, but there is very little direct evidence to support such an opinion. However, circumstantial evidence shows that Tennyson must have been interested in what Carlyle had to offer; that Carlyle and Tennyson were personal friends; and that there are many parallels between the works of Carlyle and Tennyson. Carlyle is essentially a romantic. His attitude toward art is ambivalent, a fact which is indicative of the conflict between Carlyle's longing for beauty, goodness, and truth on the one hand, and, on the other, his realization of the difficulty in reaffirming these absolutes within the spirit of his age. -

2020 Annual 1 What’S Inside Welcome

2020 Annual 1 What’s Inside Welcome. Welcome 2 Andrew Ferguson Rugby League & the ‘Spanish Flu’ 3 Nick Tedeschi Making the Trains Run on Time 4 Hello and welcome to the first ever Rugby League Suzie Ferguson Being a rugby league fan in lockdown 5 Project Annual. Yearbooks of the past have always Will Evans Let’s Gone Warriors 6-7 been a physical book detailing every minutiae of the RL Eye Test How the game changed statisically 8-10 particular season, packed full of great memories, Jason Oliver & Oscar Pannifex statistics and history. Take the Repeat Set: NRL Grand Final 11-13 Ben Darwin Governance vs Performance 14-15 This yearbook is a twist on the usual yearbook as it 2020 NRL Season & Grand Final 16-18 not only looks at the Rugby League season of 2020, 2020 State of Origin series 19-21 but most importantly, it celebrates the immensely NRL Club Reviews Brisbane 22-23 brilliant, far-reaching and diverse community of Canberra 24-25 Canterbury-Bankstown 26-27 independent Rugby League content creators, from Cronulla-Sutherland 28-29 Australia, New Zealand, England and even Canada! Gold Coast 30-31 Manly-Warringah 32-33 This is not about one individual website, writer Melbourne 34-35 or creator. This is about a community of fans who Newcastle 36-37 are uniquely skilled and talented and who all add North Queensland 38-39 to the match day experience for supporters of Parramatta 40-41 Rugby League around the world, in ways that the Penrith 42-43 mainstream media simply cannot.