Special Collections Library Henry Madden Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plan Director De Desarrollo Urbano Del

PLAN DIRECTOR DE DESARROLLO URBANO DEL PUERTO DE TOPOLOBAMPO PLAN DIRECTOR URBANO DEL PUERTO DE TOPOLOBAMPO PAGINA 1 Paginas PRESENTACION 04 I. ANTECEDENTES…………………………………………………………….………………….….…………. 05 a. Introducción………………………………………………………………………………………..…... b. Fundamentación jurídica…………………………………………………………………..…..... 05 c. Congruencia con los niveles de planeación……………………………………..……….. 06 d. Delimitación del área de estudio……………………………………………………………... 08 e. Diagnóstico-pronóstico………………………………………………………………………....… 12 i. El ámbito subregional 14 ii. El medio físico natural iii. El medio físico transformado 1. Suelo 2. Infraestructura 3. Vivienda 4. Vialidad 5. Transporte 6. Equipamiento urbano 7. Industria 8. Turismo 9. Imagen urbana 10. Medio ambiente 11. Riesgos y vulnerabilidad iv. Los aspectos socio económicos v. La administración y gestión del desarrollo urbano vi. Análisis FODA vii. Diagnóstico-pronóstico integrado viii. Imagen objetivo II. NORMAS PARA EL CONTROL Y ADMINISTRACION DEL DESARROLLO URBANO.. a. Objetivos y metas…………………………………………………………………………….….….. 69 i. Objetivos generales y específicos 69 ii. Metas (situaciones a alcanzar en un determinado plazo) b. Dosificación del desarrollo urbano……………………………………………………..…... 78 III. POLITICAS Y ESTRATEGIAS................................................................................... a. Políticas de desarrollo urbano…………………………………………………………….…... i. Políticas de Crecimiento 81 ii. Políticas de Conservación 81 iii. Políticas de Mejoramiento PLAN DIRECTOR URBANO DEL PUERTO DE TOPOLOBAMPO PAGINA -

Sinaloa Ahome LOS MOCHIS 1085949 254737 Sinaloa Ahome

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Sinaloa Ahome LOS MOCHIS 1085949 254737 Sinaloa Ahome EL AGUAJITO 1091943 255732 Sinaloa Ahome AGUA NUEVA 1090535 255305 Sinaloa Ahome AHOME 1091020 255508 Sinaloa Ahome LOS ALGODONES 1091658 255817 Sinaloa Ahome EL AÑIL 1090445 255647 Sinaloa Ahome BACAPOROBAMPO 1090059 255429 Sinaloa Ahome BACOREHUIS 1090511 261908 Sinaloa Ahome BACHOMOBAMPO NÚMERO UNO 1091124 254532 Sinaloa Ahome BAGOJO COLECTIVO 1090704 255227 Sinaloa Ahome BENITO JUÁREZ 1090158 254625 Sinaloa Ahome SAN ISIDRO 1091504 255838 Sinaloa Ahome EL BULE 1091727 255302 Sinaloa Ahome LAS LILAS 1091133 255004 Sinaloa Ahome CERRILLOS (CAMPO 35) 1085405 255241 Sinaloa Ahome COHUIBAMPO 1090934 255631 Sinaloa Ahome EL COLORADO 1091858 254530 Sinaloa Ahome COMPUERTAS 1090109 255033 Sinaloa Ahome CUCHILLA DE CACHOANA 1090638 255239 Sinaloa Ahome CHIHUAHUITA 1090318 260917 Sinaloa Ahome LA DESPENSA 1091623 255935 Sinaloa Ahome DIECIOCHO DE MARZO 1090505 255136 Sinaloa Ahome DOLORES HIDALGO 1090106 262044 Sinaloa Ahome EMIGDIO RUIZ 1090036 262230 Sinaloa Ahome EL ESTERO (JUAN JOSÉ RÍOS) 1085012 254547 Sinaloa Ahome FELIPE ÁNGELES 1090225 255207 Sinaloa Ahome FLOR AZUL 1090030 255212 Sinaloa Ahome GABRIEL LEYVA SOLANO (ZAPOTILLO DOS) 1090033 255259 Sinaloa Ahome GUILLERMO CHÁVEZ TALAMANTES 1090143 262000 Sinaloa Ahome GOROS NÚMERO DOS 1090239 255237 Sinaloa Ahome GOROS PUEBLO 1090442 255716 Sinaloa Ahome LAS GRULLAS MARGEN DERECHA 1092015 255242 Sinaloa Ahome LAS GRULLAS MARGEN IZQUIERDA 1091940 255115 Sinaloa Ahome HUACAPORITO 1091445 260343 Sinaloa -

X- Banco De Proyectos Residencia Profesional

X- BANCO DE PROYECTOS RESIDENCIA PROFESIONAL BIOLOGÍA BANCO DE PROYECTOS PARA RESIDENCIA PROFESIONAL BIOLOGÍA Tipo de proyecto No. de No. Institución/Empresa Nombre del proyecto interno/externo estudiantes Biología floral del mangle rojo Rhizophora mangle y el mangle blanco Laguncularia racemosa). 1 TECNM-ITLM INTERNO 1 2 TECNM-ITLM Elaboración y evaluación de una composta de residuos de hortalizas de uso doméstico. INTERNO 1 3 TECNM-ITLM Elaboración y evaluación de una composta a partir de follaje de leguminosas. INTERNO 1 4 TECNM-ITLM El cultivo de arándano en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 5 TECNM-ITLM El cultivo de mango e el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 6 TECNM-ITLM Buenas prácticas agrícolas en campo y empaques de hortalizas y frutas en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 7 TECNM-ITLM El tizón tardio de la papa y el tomate en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 8 TECNM-ITLM La mosquita blanca en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 9 TECNM-ITLM Malezas perennes en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 10 TECNM-ITLM Roedores de importancia agricola en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 Tipo de proyecto No. de No. Institución/Empresa Nombre del proyecto interno/externo estudiantes 11 TECNM-ITLM Plantas medicinales en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 12 TECNM-ITLM El gusano cogollero del maizen el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 13 TECNM-ITLM Áfidos de importancia económica en el norte de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 14 TECNM-ITLM Elaboración de un manual de mamíferos terrestres del estado de Sinaloa. INTERNO 1 Diversidad de almejas de la familia Veneridae en las islas del norte de Sinaloa. -

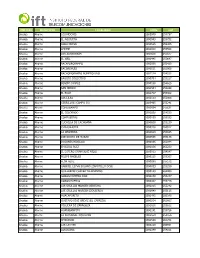

Horarios De Servicios a Industrias

Horarios de Servicios a Industrias Estación ZVP Cliente Capacidad Tren Salida desde Hora de Hora Límite de Salida Documentación Hora Local Sinaloa 1 T1076 La Cruz 01-833-94 Asociación De Agricultores Del Río Elota, AC 6 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 2 T1076 La Cruz 01-710-94 Comercializadora de Granos Patrón, SA CV 50 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 3 T1076 La Cruz 01-720-94 Graneros Unidos, SA CV (Jova) 12 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 4 T1076 La Cruz 01-702-94 Productores Agrícolas de Elota 25 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 5 T10125 Obispo 01-831-94 Granos y Forrajes Marfil, SA CV (ASASA) 75 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 6 T1015 Oso 01-831-94 Comercializadora de Granos Patrón, SA CV 50 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 7 T1015 Oso 01-836-94 Bodegas Alfer, SA CV 14 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 8 T1008 Quila 01-801-94 Asociación de Agricultores del Río San Lorenzo, AC 12 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 9 T1008 Quila 01-706-94 ADM México, SA CV 8 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 10 T1008 Quila 01-701-94 Graneros Unidos, SA CV (Jova) Vía Público 25 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 11 T0992 Alhuate 01-835-94 Comercializadora de Granos Patrón, SA CV 22 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 12 T0992 Alhuate 01-833-94 Granero El Alhuate, SA CV 16 TMACU Mazatlán 23:20 18:00 13 T0976 San Rafael 01-702-94 Cargill de México, SA CV 75 YCU03 Culiacán 10:00 07:00 14 T0976 San Rafael 01-801-94 Agrícola Sijo, SA CV 75 YCU03 Culiacán 10:00 07:00 15 T0956 Culiacán 01-735-94 Almacenes Colhuacan, SA CV 8 YCU04 Culiacán 19:00 16:00 16 T0956 Culiacán 02-748-94 Unión Nacional de Productores y Exportadores de Garbanzo -

Centro De Integracion Juvenil A.C

SECRETARÍA DE ADMINISTRACIÓN Y FINANZAS DEL GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE SINALOA UNIDAD DE INVERSIONES PROYECTO DE CARTERA DE INVERSIONES Inversión de proyectos registrados en la UI de la SHCP $ 46,837 mdp N° de proyectos Inversión de proyectos registrados en la UI del Estado $ 3,990 mdp N° de proyectos Total $ 50,827 mdp NO. NOMBRE DEL PROYECTO MUNICIPIO TIPO DE PROYECTO MONTO CONSECUTIVO CENTRO DE INTEGRACION JUVENIL A.C. LOS EDUCACIÓN 1 AHOME $ 844,615.08 MOCHIS(CONSTRUCCION DE TECHUMBRE METALICA) PÚBLICA REMODELACIÓN DEL ESTADIO DR. JUAN NAVARRO ESCOTO EN LA 2 AHOME DEPORTE $ 12,000,000.00 CIUDAD DE LOS MOCHIS CONSTRUCCIÓN DE DRENAJE PLUVIAL NUEVO SIGLO EN EL 3 AHOME URBANIZACIÓN $ 11,000,000.00 MUNICIPIO DE AHOME SINALOA PAVIMENTACIÓN CON CONCRETO HIDRÁULICO DE LAS CALLES: "SALVADOR ALVARADO" ENTRE CARRETERA A ENTRONQUE CON CARRETERA CULIACÁN-EL DORADO Y CALLE ARBACO, CALLE "ARBACO" ENTRE CALLE SALVADOR ALVARADO Y CALLE COSTA 4 AHOME URBANIZACIÓN $ 26,011,720.67 RICA, Y CALLE "COSTA RICA" ENTRE CALLE ARBACO Y CARRETERA A ENTRONQUE CON CARRETERA CULIACÁN-EL DORADO, CON LONGITUD DE 2508.19 MTS. UBICADO EN LA SINDICATURA DE COSTA RICA, CULIACÁN, SINALOA. AMPLIACIÓN DE BIBLIOTECA PÚBLICA “HUMBERTO RODRIGO 5 SÁNCHEZ”, UBICADA EN HIGUERA DE ZARAGOZA, MUNICIPIO DE AHOME CULTURA $ 590,000.00 AHOME, SINALOA PAVIMENTACION CON CONCRETO ASFALTICO DEL LIBRAMIENTO INFRAESTRUCTURA 6 AHOME $ 4,653,196.28 DE LUISIANA CARRETERA MODERNIZACIÓN Y AMPLIACIÓN DEL CAMINO SECTOR JURICAHUI PAVIMENTACIÓN DE 7 AHOME SAN MIGUEL ZAPOTITLÁN, DEL KM 0+000 AL KM 2+920, Y DEL KM CAMINOS $ 15,312,101.25 0+700 AL KM 0+915, EN EL MUNICIPIO DE AHOME CARRETERA EL CARDAL-CAMPO AGRÍCOLA Y PUENTE VEHICULAR 8 PARA E.C. -

La Secretaria De Comunicaciones Y Transportes Informa Que El Objetivo

CENTRO SCT SINALOA COMUNICADO No. 002 Modernizará SCT Diversos Caminos Rurales y Carreteras Alimentadoras Las obras beneficiarán a los municipios de Guasave, Salvador Alvarado, El Fuerte, Choix, Mocorito, Navolato y Culiacán. La Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes a través de su Centro SCT en Sinaloa, invertirá 132.8 millones de pesos para modernización de ocho caminos rurales y carreteras alimentadoras, ubicados en los municipios de Guasave, Salvador Alvarado, El Fuerte, Choix, Mocorito, Navolato y Culiacán. Estas obras corresponden a diversas licitaciones públicas nacionales emitidas en días pasados, y mediante las cuales se renovarán 24.6 kilómetros de caminos rurales y 5 kilómetros de carreteras alimentadoras, distribuidos en los siguientes proyectos: Calle 10, Tramo México 15 - Canal Alto Valle de Huyaqui-La Compuerta, del municipio de Guasave Cruz Segunda-Guadalupe Victoria, del municipio de Culiacán México 15-Comunidad 15 de Septiembre, Vía 27 de Noviembre, del municipio Salvador Alvarado La Despensa-Jitzamuri, tramo San Pablo-Jitzamuri, del Municipio de Ahome Eje Carretero Topolobampo-Ojinaga, tramo El Fuerte-Choix, del municipio de Mocorito Mocorito-San Benito, del municipio de Mocorito Rosa Morada-Agua Pepito, tramo Iraguato–Aguapepito del municipio de Navolato Los fallos se dieron una vez hecha la evaluación de las propuestas técnicas y económicas presentadas por las empresas participantes, de conformidad con los artículos 39 de la Ley de Obra Públicas y Servicios relacionados con las mismas, y se adjudicó el contrato a quien presentó la propuesta económicamente más conveniente. Consulte nuestra página: www.sct.gob.mx // email: [email protected] // 01 6671 67 19 64 CENTRO SCT SINALOA COMUNICADO No. -

Plan Estratégico De Turismo Del Estado De Sinaloa Informe Ejecutivo

PLAN ESTRATÉGICO DE TURISMO DEL ESTADO DE SINALOA INFORME EJECUTIVO INTRODUCCIÓN EL TURISMO, UNA VISIÓN DE ESTADO En el proceso VISIÓN COMÚN coordinada por el Gobierno de Sinaloa y CODESÍN durante 2006, en el que participaron centenares de sinaloenses de las más diversas profesiones, se define unánimemente al turismo como una oportunidad básica de desarrollo, y como vocación natural del Estado. 2 EL PLAN AVANTE, UN CONJUNTO DE PLANES INTEGRADOS A partir de la decisión del Gobierno del Estado de Sinaloa de considerar el turismo como un sector prioritario para el desarrollo económico y social, se han puesto en marcha una serie de iniciativas, dirigidas todas ellas al logro de este gran objetivo, por la vía técnica de la preparación de planes y programas de largo plazo que establezcan las estrategias de futuro y los programas y acciones para alcanzarlas. Asimismo, se ha trabajado en un proceso de integración que se refleja en el esquema siguiente: El Plan Avante, Plan Estratégico de Turismo de Sinaloa, se configura así como el elemento integrador de los diferentes Programas especializados realizados por Fonatur, Sectur y el Consejo de Promoción de México. Asimismo, integra otros planes y programas de carácter local y también los del sector privado, con el objetivo de ser el referente del futuro turístico de Sinaloa. Cabe, por lo tanto, entender el Plan Avante como un elemento que integra todas las propuestas e iniciativas existentes, incorporando, además, otras no consideradas en los diferentes estudios específicos. 3 El PLAN AVANTE se llevó a cabo durante diez meses del año 2006, con una metodología internacional y con la participación de más de dos mil actores del sector turístico (público y privado): 1. -

Mexico's National Guard: When Police Are Not Enough

Mexico’s National Guard: When Police are Not Enough By Iñigo Guevara Moyano January 2020 GLOSSARY OF TERMS AND ACRONYMS AFI Federal Investigations Agency, 2001-2012 AMLO Andres Manuel Lópes Obrador, President of Mexico 2018-2024 CNS National Commission of Security, SSP reorganized under SEGOB by EPN CUMAR Unified Center for Maritime and Port Protection, a Navy-led organization established to provide law enforcement functions in a Mexican port EPN Enrique Peña Nieto, President of Mexico 2012-2018 Gendarmeria a military-trained/civilian-led paramilitary force, part of the PF, est 2014 PF Federal Police, est 2009 PFP Federal Preventive Police (1999-2009) PGR Attorney General’s Office (Federal) PAN National Action Party, right-wing political party est. 1939 PM Military Police, deployed in support of law enforcement PN Naval Police – originally similar to Military Police, but in its recent form a Marine infantry force deployed in support of law enforcement PRD Democratic Revolution Party, left wing political party est. 1989 PRI Institutional Revolutionary Party, center-left wing political part est. 1929 SCT Secretariat of Communications and Transports SEDENA Secretariat of National Defense, comprising Army and Air Force SEGOB Secretariat of Governance, similar to a Ministry of Interior SEMAR Secretariat of the Navy SSP Secretariat of Public Security (2000-2012) SSPC Secretariat of Security and Citizen Protection est.2018 UIN Naval Intelligence Unit, est. 2009 UNOPES Naval Special Operations Unit UAV Unmanned Aerial Vehicle 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 1. The Origins of the National Guard ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Enter the democratic era of competitive elections and out goes the PRI ...................................... -

Censo General De Habitantes 30 De Noviembre De 1921 Estado De

ESTADOS UNIDOS MEXIOANOS O[PARTAM[NTO U[ lA ESTADISTICA NACIONAl CENSO GENERAL DE HABI1~ANTES 30 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 1921 ESTADO DE SIN ALOA_ ]Y.[ El:X:: I e o TALLERES GRA.FIOOS DE LA. NA,eIaN :1928 ESTADO DE SINALOA IN""DIOE PRIMERA PARTE TERCERA PARTE Págs. Datos Geográfico~ ............................... : ....... .. 3 SEGUNDA PARTE División Territorial Cuadros del Censo de Habitantes Lista alfabética de localidades ......... (( lübul y Sexo»... ........ .............. ...... ...... ......... 1 9 Listas de localidades de los siguientes Municipios: ((Grupos de eda.des y tanto por ciento que tGpresen- Ahome ................................................ .. U8 ta cada grupo sobre el total de habitantes»........ 20 Angostura ............................................. lüH ((Bazas» ...... " ........ " ................................. 20 Badiraguato ...... " ................................... 70 (( Defl'ctos Físicos y ~lentalesl) ............... .... ...... 21 Concordia ............................................. .. 74 «Población Extranjera». ........ ....... ............ ...... 22 Cosalá .................................................. .. 77 «Nacionalidad Actual» ...... ......... ..................... 23 Culiacán .............................................. 79 «Nacionalidad Actual, adquirida por naturaliza- Choix .................................................... 83 ciÓn))... ........ ......... .......... ........ ........ ......... 23 inaloa Elota., .................................................. 87 «ldiorna Nativo»........ -

Sinaloa Textile Sector

Sinaloa Textile Sector SINALOA OBJECTIVE Sustainable growth and diversification of our economy in line with global market trends. INTRODUCTION THE STRATEGIC LOCATION OF THE STATE, THE AVAILABILITY OF NATURAL AND HUMAN RESOURCES, AND A FAVORABLE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT PROVIDE AN EXCELLENT OPPORTUNITY FOR INVESTMENT PROJECTS, IN PARTICULAR THOSE AIMED AT THE NORTH AMERICAN MARKET (NAFTA). LOCATED ON THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST OF MEXICO, SINALOA HAS DIRECT ACCESS TO PACIFIC RHIM COUNTRIES THROUGH ITS TWO PORTS. SINALOA HAS OTHER UNIQUE ADVANTAGES; ITS COMMUNICATIONS NETWORK VIA HIGHWAY, RAIL, SEA, AND AIR AND THE ABUNDANCE OF KEY RESOURCES; WATER AND LABOR. THESE TWO KEY RESOURCES WERE DETERMINING FACTORS IN DEFINING OUR OBJECTIVE; TO CONVERT SINALOA INTO AN IMPORTANT TEXTILE CENTER FOLLOWING A COMPREHENSIVE PLAN TO DEVELOP THE VERTICAL INTEGRATION OF THE INDUSTRY, WHILE COMPLYING WITH ENVIRONMENTAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS CRITERIA. Page 01 Sinaloa Textile Sector State Profile SINALOA is located on the northwest part of Mexico, 500 miles south from the U.S. border. Its strategic location provides an advantage for distribution from U.S. to Asia and Central American countries. The State has a total area of 23 thousand sq.mi. 3% of the country's total. On the west it is bordered by the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Cortez with 400 miles of coastline. During 8 months of the year temperatures averages 74°F, the remaining 4 months, temperature average 84.2°F. Annual average temperature is 77°F with 68% average humidity. Infraestructure CHIHUAHUA TEXAS SONORA ARIZONA CHIHUAHUA TEXAS SONORA ARIZONA LOS MOCHIS GUASAVE LOS MOCHIS CULIACAN GUASAVE Our highway TOPOLOBAMPO system provides MONTERREY easy accessibility DURANGO to the U.S. -

Diapositiva 1

TTOOPPOOLLOOBBAAMMPPOO AA NNeeww PPoorrtt IInn tthhee PPaacciiffiicc OOcceeaann LOCATION Topolobampo is located in the north of Sinaloa, on the Pacific Ocean in Mexico. LOCATION 19ë04'002º NORTH 104ë19'005º WEST TOPOLOBAMPO STATES OF HINTERLAND ·SINALOA ·BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR ·SONORA ·CHIHUAHUA LIMITS OF THE PORT PLANTA TERMOELECTRICA C.F.E. HIS OC M OS A L DARSENA ESCUELA TÉ CNICA No. 9 CLUB NAUTICO TRANSBORDADORES ZONA (SEMATUR) SECRETARIA HABITACIONAL DE MARINA TOPOLOBAMPO CERRO DEL CHIVERO CERRO DEL RODADERO BASCULA CERRO CERRO DE GALLINAS DEL VIGIA TOPOLOBAMPO BAY L IM IT E D E R E C CFE IN TO I P O R T U X A E R M FeI deral Government granted in concession to API an area of E O P 301 hectares; 191 zone of water, and 110 zone of land. LIMITE DE RECINTO PORTUARIO CERRO SAN CARLOS AREAS OF THE PORT OF TOPOLOBAMPO 1. Propetopo Dock no.1 2. Propetopo Dock no. 2 3. General Cargo Dock 4. Ferry Dock 5. Fishing Dock (Cooperative Society) 6. Standard Dock 7. Repair Dock (Bercovich) 8. Pemex Dock 9. Nautical Club Dock 10. Food Processing Dock (Batamote) 11. East Fishing Dock 12. North Fishing Dock 13. Maritime Gas Station Dock 14. Container Dock 15. Transoceanic Dock 16. General Cargo Yard 17. Transit Warehouse No.1 18. Main Warehouse No. 2 19. Shed 20. Topolob ampo Transoceanic Terminal 21. Administrative Building of API 22. Sematur Yard 23. Reserve Zone 24. Propetopo Terminal 25. API’s Ferry Dock 26. Container Dock 27. Custom house 28. Cemex Dock and Installations ZONE OF EXTENSION PLANTA TERMOELECTRICA C.F.E. -

Sinaloa : Datos Por Ejido Y Comunidad Agraria

DIRECTORIO DE EJIDOS Y COMUNIDADES AGRARIAS DE SINALOA (por municipio) EJIDO POLIGONO EJIDAL LOCALIDAD MUNICIPIO AHOME EJIDO 18 DE MARZO DOT. 18 DE MARZO 18 DE MARZO AHOME 1RA. AMPL. 1B DE MARZO AHOME EJIDO 20 DE NOVIEMBRE DOT. 20 DE NOVIEMBRE 1/3 DOT. 20 DE NOVIEMBRE 2/3 AHOME DOT. 20 DE NOVIEMBRE 3/3 AHOME EJIDO 20 DE NOVIEMBRE NO. 2 DOT. 20 DE NOVIEMBRE NO. 2 AHOME E J ID O 5 D E M A Y O DOT. 5 DE MAYO EJIDO CINCO DE MAYO AHOME EJIDO AGUA NUEVA DOT. AGUA NUEVA 1/2 AHOME DOT. AGUA NUEVA 2/2 A G U A N U E V A AHOME EJIDO AGUILA AZTECA DOT. AGUILA AZTECA 1/2 AHOME AHOME ESMERALDA, LA AHOME DOT. AGUILA AZTECA 2/2 SAN ANTONIO DE SALLAS AHOME EJIDO AHOME # 1 (INDIVIDUALISTA) DOT. AHOME # 1 (INDIVIDUALISTA) AHOME EJIDO AHOME COLECTIVISTA DOT. AHOME COLECTIVISTA 1/2 CAMPO DE FELIPE MORENO AHOME DOT. A H O M E C O L E C T IV IS T A 2/2 AHOME AHOME EJIDO AHOME INDIVIDUAL DOT. AHOME INDIVIDUAL 1/2 AHOME DOT. AHOME INDIVIDUAL 2/2 AHOME EJIDO AHOME INDIVIDUAL NO. 2 DOT. AHOME INDIVIDUAL NO. 2 1/2 AHOME DOT. AHOME INDIVIDUAL NO. 2 2/2 AHOME EJIDO ALFONSO G. CALDERON DOT. ALFONSO G. CALDERON CIMARRON. EL E J ID O B A C H O C O il DOT. B A C H O C O íl BACHOCO DOS (MACOCHIN) AHOME 1R A . A M P L B A C H O C O II C E R R O C A B E Z O N N O .