Editor. “Alec Soth's Guide to Photography.” I-D. October 24, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Parr, Eric Poitevin and Viviane Sassen Unveil New Commission That Echo the Spirit of the Venue

From 14 May to 20 Octobe r 2019 For its twelfth contemporary art event, the Palace of Versailles invites 5 photographers from around the world to the Estate of Trianon, from 14 May 2019 to 20 October 2019. The next contemporary art exhibition at Versailles will be held in the intimate setting of Trianon. For the 2019 event, Dove Allouche, Nan Goldin, Martin Parr, Eric Poitevin and Viviane Sassen unveil new commission that echo the spirit of the venue. Their works, which combines creation and heritage, reveal a new Versailles. Curatorship Jean de Loisy, director of the Ecole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris Alfred Pacquement, Contemporary Art Curator at Versailles Architect scenographer Hala Wardé & her studio HW architecture PRESS CONTACTS CHÂTEAU DE VERSAILLES Hélène Dalifard, Aurélie Gevrey, Violaine Solari, Élodie Vincent [email protected] / +33 (0)1 30 83 75 21 OPUS 64 Valérie Samuel, Arnaud Pain et Fédelm Cheguillaume [email protected] [email protected] + 33 (0)1 40 26 77 94 FOREWORD The twelfth season of the Versailles contemporary art exhibition leads us as if through the antique darkroom of five photographers – Dove Allouche, Nan Goldin, Martin Parr, Eric Poitevin and Viviane Sassen – through their memories and dreams, and ways of seeing, revealing their visions of Versailles, another Versailles. For the first time, the Château of Versailles has commissioned artists to produce new works. In this instance, images that condense and pare down their thoughts on this elusive place. Nearly two hundred years after its invention, photography and its new techniques make Versailles itself as “new” a subject now as it was at the turn of the 20th century. -

Alec Soth's Journey: Materiality and Time Emily Elizabeth Greer

Alec Soth’s Journey: Materiality and Time Emily Elizabeth Greer Introduction The photographer Alec Soth is known for series of images and publications that encapsulate his travels through time and place within the American landscape. Each grouping of photographs uses a specific medium and geographical orientation in order to explore unique journeys and themes, such as the loneliness and banality of strangers in a public park, religion and debauchery in the Mississippi Delta, and the isolation of hermits in the valleys of rural Montana. Yet how are we to understand the place of these smaller journeys within Soth’s larger artistic career? How are these publications and series connected to one another, and how do they evolve and change? Here, I will consider these questions as they relate to the specific materials within Soth’s work. Using material properties as a framework illuminates the way in which each series illustrates these specific themes, and also how each grouping of images holds a significant place within the artist’s larger photographic oeuvre. Throughout Alec Soth’s career, his movement between mediums has evolved in a manner that mirrors the progression of themes and subject matter within his larger body of work as a whole. From his earliest photographic forays in black and white film to his most recent digital video projects, Soth creates images that depict a meandering passage through time and place.1 His portraits, still lifes, and landscapes work together to suggest what one might call a stream of conscious wandering. The chronological progression of materiality in his works, from early black and white photography to large format 8x10 color images to more recent explorations in digital photography and film, illuminates the way in which each medium is used to tell a story of temporality and loneliness within the American landscape. -

BBC Four Winter/Spring 2007

bbc_four_Autmun_2006.qxd:Layout 1 16/1/07 10:42 Page 1 Winter/Spring Highlights 2007 bbc.co.uk/bbcfour bbc_four_Autmun_2006.qxd:Layout 1 16/1/07 10:42 Page 3 The Edwardians – People Like Us? In just a few years at the start of the 20th century, Britain changed in unimaginable ways. From the first foray into aviation, to the invention of labour-saving devices for the home, to the rise of “the brand”, and the birth of not only “the High Street”, but also of the “commuter class”, mass consumerism and tabloid journalism, the Edwardians lived lives not too distant from our own. This new BBC Four season investigates, interrogates and celebrates the richness and excitement of this pioneering and world-changing time. 01 bbc_four_Autmun_2006.qxd:Layout 1 16/1/07 10:42 Page 5 The season includes some of the era’s best-known names, from literary giants such as George and Weedon Grossmith and Saki, to the doyenne of the music hall, Marie Lloyd. Along the way, it also uncovers lesser-known figures. It hears about trailblazers in the fields of social reform, journalism, photography, entrepreneurship and technical invention, uncovering what it really felt like to be Edwardian. Dramas The season launches with Andrew Davies’s brilliant, two-part adaptation of the classic comedy novel The Diary Of A In a compelling drama about the life of one of the biggest stars Nobody, starring Hugh Bonneville as the wonderfully of the time, Marie Lloyd – starring Jessie Wallace as Marie – pompous diarist Mr Charles Pooter – the Victor Meldrew of the season exposes the seedy underbelly of this peculiarly his day – Edwardian entertainment. -

Artist's Notes the Rhubarb Triangle & Other Stories: Photographs by Martin Parr

ARTIST’S NOTES THE RHUBARB TRIANGLE & OTHER STORIES: PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARTIN PARR www.hepworthwakefield.org THE RHUBARB TRIANGLE & OTHER STORIES: PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARTIN PARR 4 February - 12 June 2016 INTRODUCTION and leisure events, or commenting on the consumerism of western culture in the documentation of everyday Martin Parr, the best-known British photographer objects and food in his series Common Sense (1995 – 9) of his generation, was born in Epsom, Surrey in exhibited in Gallery 10, themes of work and leisure can 1952. As a young boy, Parr’s interest in photography be traced throughout his work. was encouraged by his grandfather, George Parr, a Yorkshireman and keen amateur photographer. His Parr’s earlier work focussed on small social groups grandfather gave him his first camera and taught him within Britain, shown within series such as The Non- how to take photographs, process the film and make Conformists (1975 – 80) on display in Gallery 7. Over prints. Parr followed this interest and went on to study the past twenty years he has increasingly worked photography at Manchester Polytechnic from 1970 – 73. abroad, and his work has reflected this change, exploring themes of globalisation and the rise of Since studying in Manchester Parr has worked on international tourism, which can be seen within his work numerous photographic projects; he has developed exhibited in Gallery 10. an international reputation for approach to social documentary, and his input to photographic culture Changing photography and use of technology: within the UK and abroad. He also makes films, curates exhibitions and festivals, teaches, is president Parr’s first major series of work,The Non-Conformists, of the co-operative agency Magnum Photos, and was photographed in black and white, partially for collaborates with publishers to produce books on other its suitability to the subject and the nostalgic look at photographers. -

Our Choice of New and Emerging Photographers to Watch

OUR CHOICE OF NEW AND EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS TO WATCH TASNEEM ALSULTAN SASHA ARUTYUNOVA XYZA BACANI IAN BATES CLARE BENSON ADAM BIRKAN KAI CAEMMERER NICHOLAS CALCOTT SOUVID DATTA RONAN DONOVAN BENEDICT EVANS PETER GARRITANO SALWAN GEORGES JUAN GIRALDO ERIC HELGAS CHRISTINA HOLMES JUSTIN KANEPS YUYANG LIU YAEL MARTINEZ PETER MATHER JAKE NAUGHTON ADRIANE OHANESIAN CAIT OPPERMANN KATYA REZVAYA AMANDA RINGSTAD ANASTASIIA SAPON ANDY J. SCOTT VICTORIA STEVENS CAROLYN VAN HOUTEN DANIELLA ZALCMAN © JUSTIN KANEPS APRIL 2017 pdnonline.com 25 OUR CHOICE OF NEW AND EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHERS TO WATCH EZVAYA R © KATYA © KATYA EDITor’s NoTE Reading about the burgeoning careers of these 30 Interning helped Carolyn Van Houten learn about working photographers, a few themes emerge: Personal, self- as a photographer; the Missouri Photo Workshop helped assigned work remains vital for photographers; workshops, Ronan Donovan expand his storytelling skills; Souvid fellowships, competitions and other opportunities to engage Datta gained recognition through the IdeasTap/Magnum with peers and mentors in the photo community are often International Photography Award, and Daniella Zalcman’s pivotal in building knowledge and confidence; and demeanor grants from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting altered and creative problem solving ability keep clients calling back. the course of her career. Many of the 2017 PDN’s 30 gained recognition by In their assignment work, these photographers deliver pursuing projects that reflect their own experiences and for their clients without fuss. Benedict Evans, a client interests. Salwan Georges explored the Iraqi immigrant says, “set himself apart” because people like to work with community of which he’s a part. Xyza Bacani, a one- him. -

Notable Photographers Updated 3/12/19

Arthur Fields Photography I Notable Photographers updated 3/12/19 Walker Evans Alec Soth Pieter Hugo Paul Graham Jason Lazarus John Divola Romuald Hazoume Julia Margaret Cameron Bas Jan Ader Diane Arbus Manuel Alvarez Bravo Miroslav Tichy Richard Prince Ansel Adams John Gossage Roger Ballen Lee Friedlander Naoya Hatakeyama Alejandra Laviada Roy deCarava William Greiner Torbjorn Rodland Sally Mann Bertrand Fleuret Roe Etheridge Mitch Epstein Tim Barber David Meisel JH Engstrom Kevin Bewersdorf Cindy Sherman Eikoh Hosoe Les Krims August Sander Richard Billingham Jan Banning Eve Arnold Zoe Strauss Berenice Abbot Eugene Atget James Welling Henri Cartier-Bresson Wolfgang Tillmans Bill Sullivan Weegee Carrie Mae Weems Geoff Winningham Man Ray Daido Moriyama Andre Kertesz Robert Mapplethorpe Dawoud Bey Dorothea Lange uergen Teller Jason Fulford Lorna Simpson Jorg Sasse Hee Jin Kang Doug Dubois Frank Stewart Anna Krachey Collier Schorr Jill Freedman William Christenberry David La Spina Eli Reed Robert Frank Yto Barrada Thomas Roma Thomas Struth Karl Blossfeldt Michael Schmelling Lee Miller Roger Fenton Brent Phelps Ralph Gibson Garry Winnogrand Jerry Uelsmann Luigi Ghirri Todd Hido Robert Doisneau Martin Parr Stephen Shore Jacques Henri Lartigue Simon Norfolk Lewis Baltz Edward Steichen Steven Meisel Candida Hofer Alexander Rodchenko Viviane Sassen Danny Lyon William Klein Dash Snow Stephen Gill Nathan Lyons Afred Stieglitz Brassaï Awol Erizku Robert Adams Taryn Simon Boris Mikhailov Lewis Baltz Susan Meiselas Harry Callahan Katy Grannan Demetrius -

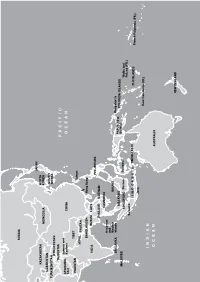

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

Asia and Oceania Jack Dentith, Emily Hong, Irwin Loy, Farah Mihlar, Daniel Openshaw, Jacqui Zalcberg Right: Uighurs in Kazakhstan Picking Fruit from Central a Tree

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville PAPUA NEW MALAYSIA SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Jack Dentith, Emily Hong, Irwin Loy, Farah Mihlar, Daniel Openshaw, Jacqui Zalcberg Right: Uighurs in Kazakhstan picking fruit from Central a tree. Carolyn Drake/Panos. which affects the health of the most vulnerable people living in the region. In March, the Asian Asia Development Bank (ADB) reported that the shrinking of the Aral Sea and drying up of two Daniel Openshaw major rivers, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, would particularly affect Karakalpakstan – an inority groups live in some of the autonomous region of Uzbekistan, home to the poorest regions of Central Asia; majority of the country’s Karakalpak population, M Pamiris in Gorno-Badakhshan as highlighted in MRG’s 2012 State of the World’s Autonomous Province in Tajikistan; Uzbeks Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. in South Kazakhstan province; Karakalpaks in In an already poor region, climate change Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan region; and high is especially significantly affecting the most numbers of Uzbeks and Tajiks in Kyrgyzstan’s vulnerable. Most people in Karakalpakstan Ferghana Valley. Poverty has a direct impact depend on agriculture, so water shortages have on their health. -

Martin Parr in Mexico: Does Photographic Style Translate?

Journal of International and Global Studies Volume 3 Number 1 Article 4 11-1-2011 Martin Parr in Mexico: Does Photographic Style Translate? Timothy R. Gleason Ph.D. University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs Part of the Anthropology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Gleason, Timothy R. Ph.D. (2011) "Martin Parr in Mexico: Does Photographic Style Translate?," Journal of International and Global Studies: Vol. 3 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs/vol3/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International and Global Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Martin Parr in Mexico: Does Photographic Style Translate? Timothy R. Gleason, Ph.D. University of Wisconsin Oshkosh [email protected] Abstract This study analyzes Martin Parr’s 2006 photobook, Mexico. Parr is a British documentary photographer best known for a direct photographic style that reflects upon “Englishness.” Mexico is his attempt to understand this foreign country via his camera. Mexico, as a research subject, is not a problem to solve but an opportunity to understand a photographer’s work. Parr’s Mexico photography (technique, photographic content, and interest in globalization, economics, and culture) is compared to his previous work to explain how Parr uses fashion and icons to represent a culture or class. -

BBC One Moves Away from Circles, Towards 'Oneness'

BBC One Moves Away From Circles, Towards 'Oneness' 01.30.2017 Whether it's hippos swimming in a loop, the top of a lighthouse, or children holding hands while playing "ring around the roses," British viewers have gotten very used to seeing circles on their screens. For a decade, anyone tuning into BBC One - the British broadcaster's original and still most popular channel - will have seen its iconic loops, hoops and rings in between shows. But inevitably the time has come for a change, and something of a re-brand. On New Year's Eve the ident was finally retired, to be replaced by something completely new. The brief: to update BBC One with the times and, says Charlotte Moore, director of BBC Content, to ensure that the channel is fit to "evolve creatively." Cue a major challenge to the BBC's in-house agency, BBC Creative, to come up with something bold and new to bring the BBC up with modern times. For BBC Creative, it was one of the first big tests since its inception in February 2016, after the corporation's outsourced contract with Red Bee Media had run its course and the decision was made to bring the work back in house. Under the leadership of director Justin Bairamian, the team set about finding the right creative vision - one which captured the diversity of modern Britain in an original way and promoted a sense of shared identity and of people coming together as one. It was out of this spirit that theme was found and a title for the new ident was born: "Oneness." The next and crucial step was getting the right creative mind on board. -

Darkhighway Textpluswork.Pdf

The Dark Highway Paul Wenham-Clarke Curated by Aaron Schuman Supporting essay by Paul Allen THE ARTIST'S SPACE “I started out as a commercial photographer working for corporate clients such as British Telecom, Hitachi and Hoover, and was one of the first practitioners to embrace the opportunities and potential of digital technologies. This activity generally involved me in being creative in response to the demands of others and producing short-lived outcomes with no social impact beyond generating sales. Throughout this time I was shooting small personal projects about other people’s lives, from documenting the last employees in a bus station before it was knocked down to make way for a shopping mall, to recording the fading charm of Weymouth’s seafront. The shift was realising that I wanted to undertake a more substantial piece of work about a subject of social importance; the result was When Lives Collide. Subsequent projects continued to explore ideas about the road that ultimately led to an aspect of it that was concerned with how I felt about the subject matter rather than it being documentary research. Sacrifice the Birdsong came from a compulsion to explore a lifelong interest in wildlife and mourn its loss on our roads through images that engage the public rather than the art community alone. The Dark Highway is a summary of these works and a record of my changing working processes.” Paul Wenham-Clarke, 2014 Megan on a cold minus 5 degree morning, from The Westway 3 STYLES, STRATEGIES AND SUBJECTS CURATOR'S VIEWPOINT n one sense, The Dark Highway is a somewhat misleading title, in that it implies that the photographic works included in this exhibition are situated in the middle Iof a road, albeit an ominous and metaphoric one. -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013

Focus on health minority rights group international State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013 Events of 2012 State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20131 Events of 2012 Front cover: A Dalit woman who works as a Community Public Health Promoter in Nepal. Jane Beesley/Oxfam GB. Inside front cover: Indigenous patient and doctor at Klinik Kalvary, a community health clinic in Papua, Indonesia. Klinik Kalvary. Inside back cover: Roma child at a community centre in Slovakia. Bjoern Steinz/Panos Acknowledgements Support our work Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate gratefully acknowledges the support of all organizations MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals who gave financial and other assistance and individuals to help us secure the rights of to this publication, including CAFOD, the European minorities and indigenous peoples around the Union and the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. world. All donations received contribute directly to our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. © Minority Rights Group International, September 2013. All rights reserved. Subscribe to our publications at www.minorityrights.org/publications Material from this publication may be reproduced Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe for teaching or for other non-commercial purposes. to our publications, which offer a compelling No part of it may be reproduced in any form for analysis of minority and indigenous issues and commercial purposes without the prior express original research. We also offer specialist training permission of the copyright holders. materials and guides on international human rights instruments and accessing international bodies.