Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICHARD III SOCIETY Patron: HRH Prince Richard, the Duke of Gloucester KG GCVO

RICHARD III SOCIETY Patron: HRH Prince Richard, The Duke of Gloucester KG GCVO APPENDIX 2 Founder: Dr S Saxon Barton Communications Manager Amanda Geary 22 Camelot Avenue Sherwood Nottingham NG5 1DW Tel: 0115 9706878/07769 800622 Email: [email protected] Website www.richardiii.net PRESS RELEASE An open letter to the Planning Committee of Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council The battle of Bosworth was one of the most significant events in English history. It is remarkable for the fact that it featured the final cavalry charge of the last English king to die in battle. This event led to the end of over three hundred years of Plantagenet rule, and the beginning of the Tudor era. Despite being a Society with a research focus firmly on events of the past, we are in no way opposed to technological progress. It was indeed more recent advances in genetics and DNA fingerprinting which allowed King Richard himself to be identified once his remains were located beneath the Social Services car park in Leicester in 2012. However, we are concerned that something as historically and culturally important as the battlefield, which has a direct relevance to the king now buried in Leicester Cathedral, will be adversely impacted by this development. We appreciate the need to test this new technology but by its nature, and bearing in mind the speed of future technological advances, it is likely to become quickly obsolete, whereas the damage done to the battlefield will be irreparable. We are therefore concerned that the battlefield will be lost for a project which may be important in the short term, but is unlikely to have a significant lasting value across centuries to come. -

Ricardian Bulletin

Ricardian Bulletin Contents Summer 2007 2 From the Chairman 3 Strategy Update 9 Society News and Notices 12 Media Retrospective 14 News and Reviews 17 The Man Himself: by Tony Goodman 20 Medieval Migration: by Peter W. Lee 22 A Proclamation Against Henry Tudor, 23 June 1485: by David Candlin 25 Hastings and the Meeting at St Paul’s: by Gordon Smith 27 Chedworth Parish Church: by Gwen & Brian Waters 29 A ‘Lost’ Medieval Document: by Lynda Pidgeon 30 Logge Notes and Queries: Helen Barker’s Miracles by Lesley Boatwright 33 Correspondence 36 Guidelines for Contributors to the Bulletin 37 The Barton Library 40 New Members 41 Australasian Convention 2007 44 Report on Society Events 52 Future Society Events 55 Branch and Group Contacts - Update 55 Branches and Groups 58 Obituaries and Recently Deceased Members 60 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to the Technical Editor, Lynda Pidgeon. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of the The Ricardian and Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. For contact details see back inside cover of the Bulletin The Ricardian Bulletin is produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee Printed by St Edmundsbury Press. © Richard III Society, 2007 1 From the Chairman ime for another issue of the Bulletin, and, all being well, you should have the 2007 edition T of The Ricardian too. -

Ricardian Bulletin Edited by Elizabeth Nokes and Printed by St Edmundsbury Press

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 Winter 2003 Richard III Society Founded 1924 In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to this period and of the role in English history of this monarch Patron HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG, GCVO Vice Presidents Isolde Wigram, Carolyn Hammond, Peter Hammond, John Audsley, Morris McGee Executive Committee John Ashdown-Hill, Bill Featherstone, Wendy Moorhen, Elizabeth Nokes, John Saunders, Phil Stone, Anne Sutton, Jane Trump, Neil Trump, Rosemary Waxman, Geoffrey Wheeler, Lesley Wynne-Davies Contacts Chairman & Fotheringhay Co-ordinator: Phil Stone Research Events Adminstrator: Jacqui Emerson 8 Mansel Drive, Borstal, Rochester, Kent ME1 3HX 5 Ripon Drive, Wistaston, Crewe, Cheshire CW2 6SJ 01634 817152; e-mail: [email protected] Editor of the Ricardian: Anne Sutton Ricardian & Bulletin Back Issues: Pat Ruffle 44 Guildhall Street, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk IP33 1QF 11 De Lucy Avenue, Alresford, Hants SO24 9EU e-mail: [email protected] Editor of Bulletin Articles: Peter Hammond Sales Department: Time Travellers Ltd. 3 Campden Terrace, Linden Gardens, London W4 2EP PO Box 7253, Tamworth, Staffs B79 9BF e-mail: [email protected] 01455 212272; email: [email protected] Librarian -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

born circa 673, was much venerated in his own time, and even more so not long after his death in 714. He ‘ enjoyed heavenly visions but also had to combat demonic temptations.’2 His whip (almost needless to say,sent in answer to a prayer to his patron saint) was used to flog the Devil. According to Fox- Davies3 the only essential difl'erence in the mitres of abbots and bishops is in the absence or presence of what we call the ribbons (infulae). JOHN RUSSELL: Bishop of Lincoln, died 1494 1449-62 Winchester, New College, etc. 1466 Archdeacon of Berkshire 1474—83 Keeper of the Privy Seal Negotiated marriage between Cicely, daughter of King Edward IV, and the future James IV of Scotland, which did not take place 1476—80 Bishop of Rochester 1480-94 Bishop of Lincoln 1483—85 Chancellor of England 1483-94 Chancellor of Oxford University It seems that the arms of the Sec of Lincoln were not used before 1495 (and then only as a seal),4 so Russell must have his mitre, but his shield cannot impale the arms of the Bishopric. His personal arms were: Blue, two golden chevronels between three silver roses.s He was evidently not of the same family as the later earls and dukes of Bedford. It could be said that the most important thing about Russell is his possible connection with the Second Continuation of the Croyland Chronicle (covering 1483—5), and it seems that one can now again agree with Kendall when he said ‘ There is considerable evidence to suggest that the materials, if not the actual writing, of most of this narrative is the work of John Russell, Bishop of Lincoln, one of Edward’s most intimate advisers and Richard’s Chancellor.“ NOTES AND REFERENCES l. -

Ricardian Register

Ricardian Register Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 45 No. 2 June, 2014 Richard III Forever Printed with permission l Mary Kelly l Copyright © 2012 In this issue: Crosby Place: A Ricardian Residence Essay: Shakespeare's Hollywood vs. History Ricardian Review 2014 AGM Inside cover (not printed) Contents Crosby Place: A Ricardian Residence 2 Essay: Shakespeare's Hollywood vs. History 5 Ricardian Review 7 From the Editor 13 2014 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 14 AGM REGISTRATION FORM 15 Member Challenge: 16 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts 18 Membership Application/Renewal Dues 19 Thomas Stanley at Bosworth 20 v v v ©2014 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical, electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval—without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions for the Register only are available at $25 annually. In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch. The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Dues are $60 annually for U.S. -

Richard III: the Self-Made King

2020 VII Richard III: The Self-Made King Michael Hicks New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019 Review by: Marina Gerzic Review: Richard III: The Self-Made King Richard III: The Self-Made King. By Michael Hicks. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019. ISBN 978-0-300-21429-1. xvi + 388 pp. $35.00. ichard III: The Self-Made King provides a thoroughly researched biography of one of England’s most infamous kings, Richard III, at a time when interest in the historical Richard is at its R zenith. Michael Hicks provides the reader with a detailed study of the world that Richard III was born into and lived in, and the political backdrop of a late medieval England dominated by the dynastic struggles of the Wars of the Roses. Hicks’s work opens with an introduction that attempts to debunk the myths surrounding Richard’s life and to tell his story as historical research reveals it to the reader. The spectres of Thomas More and Shakespeare emerge, and while Hicks attempts to dispel Tudor myths about Richard, he also finds some value in these Tudor sources and returns to them throughout his work. For example, he notes of More: “More’s characterisation therefore cannot be accepted as it stands, but neither can it be rejected out of hand. It is not purely Tudor propaganda” (6). Hicks’s introduction also looks at the more modern Ricardian reception and defence of Richard, highlighting the role of the Richard III Society in publishing sources critical to the study of Richard’s life, and also funding the archaeological dig in a Leicester carpark where remains, which have since been identified as Richard III, were discovered. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

Research Notes and Queries Bosworth 1862 0. D. Harris writes: On 6 August 1862 the annual excursion of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society took place, to Bosworth Field. Also invited were the members of the British Archaeological Association, the architectural societies of Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire, and the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society. The day' 5 events are recounted in the Associated Architectural Societies Reports and Papers. vol. 6 (1862),p p.p 243- 74; the Transactions of the LAAS, vol. 2 (1870), pp. [12-47; and the Leicester Journal and Leicester Chronicle of 8 and 9 August respectively. The convoy of fifteen or so carriages which left Leicester some time after 10.00 am. (late, because of the many last minute ticket applications) was led by the bugler of the Leicestershire Rifle Volunteers; while the supplier of most of the vehicles rode ahead to pay turnpike tolls. The first halt was Kirby Muxloe Castle, followed by Market Boswonh, to visit the church and hall. Lunch was served at the Dixie Arms Hotel, but there were not enough waiters to cope with more than two hundred excursionists, ‘whose appetites by the long drive from Leicester had been not a little sharpened‘, and some resentment seems to have been aroused. At 3.00, however, the bugle sounded, and the tourists set off for the battlefield itself. There they found waiting a crowd of three thousand, great flags to mark significant points on the field, and, on top of Ambion Hill, a large platform decorated with banners and evergreens at their disposal. -

Ricardian Bulletin Sept 2020 Text Layout 1

ARTICLES THE MISSING PRINCES PROJECT – a case study The first part of this case study suggested the possibility particularly where materials might suggest the need for a that the key to the mystery surrounding the disappearance number of enquiries to run concurrently. of the sons of Edward IV may lie with a person or persons In Part 1 (Ricardian Bulletin, March 2020, pp 42–7) we outside Richard’s government (and/or royal progress). In highlighted Henry Tudor’s post‐Bosworth delay in this regard, The Missing Princes Project is undertaking a securing London. In this final part Philippa Langley number of significant persons‐of‐interest enquiries. discusses Henry’s hesitation in relation to Robert However, as part of the wider‐ranging investigation it is Willoughby’s mission and considers the possibility that of the utmost importance that no potential avenues of the sons of Edward IV were sent north during the reign of investigation are ignored, or given undue weight, Richard III. Part 4. The fate of the sons of King Edward IV: THE AFTERMATH OF BOSWORTH 22 August to 3 September 1485 PHILIPPA LANGLEY The wider-ranging investigation (22 August–3 heir was present in the capital at the time of Richard’s September 1485) defeat. As a cold‐case police enquiry, an important part of The Post-Bosworth events under the microscope Missing Princes Project is to attempt to recreate events Let us now examine in greater detail the key post‐ without the potential contamination of hindsight. As part Bosworth period. It is important to note that Henry VII’s of its investigations there are a number of significant historian, Polydore Vergil, devoted only two lines of text events that require forensic examination. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

Résearch Notes and Queries Further Reflections on Lady Eleanor Talbot John Ashdown-Hill writes:— I am grateful to HA. Kelly for correcting my misinterpretation of the term ‘precontract'.' The word does indeed refer to any previous marriage, alleged as a challenge to a subsequent marriage, and not, as I implied in my previous article on Lady Eleanor, to a preliminary contract of marriage, similar to a betrothal. I suspect that I am not alone in having, for a time, laboured ungier a misapprehension regarding the meaning of ‘precomiact', and it is well to have the facts now clearly established. ' There is always scope for differences of opinion when one moves from the area . of facts to the realm of interpretation. Muriel' Smith2 has questioned my interpretation of Lady Eleanor as a sad,deserted wife, on the grounds that had she wished to maintain her rights as Edward IV's wife, she could have sought the powerful backing of her uncle, the Earl of Warwick. Eleanor’s kinship with Warwick was, of course, well known in the 1460s, and was well remembered at least into the early years of the following century. Both Mancini and Vergil, while not mentioning Eleanor by name, refer to Edward IV’s involvement with a member of Wani'ick’s family, and Mancini speaks specifically of a promise of marriage. Warwick himself may .have known the nature of Eleanor’s relationship with thé king, and I am convinced that his protége’ and son-in-law, the Duke of Clarence, was later well aware of it and that this fact explains both some of Clarence’s behaviour and his execution'. -

The King in the Car Park: the Discovery and Identification of Richard III Transcript

The King in the Car Park: The Discovery and Identification of Richard III Transcript Date: Tuesday, 3 November 2015 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 3 November 2015 The King in the Car Park: The Discovery and Identification of Richard III Professor Kevin Schürer Let us start by saying what this this talk is about and what it is not. Richard III is possibly one of the most famous and controversial of English kings, yet this talk is not intended to fan the flames of any controversy surrounding his reign. It will not comment on his character nor refer to how he came by the throne. Rather it will focus exclusively on the discovery of skeletal remains in Leicester in 2012 and their subsequent investigation leading to their identification as those of Richard III. It is set to make clear that what I report in this talk today is the result of a wide collaborative effort. Many experts from a range of discipline were involved and this talk draws together their work. In this regard reference must be made to colleagues at the University of Leicester: Dr Richard Buckley, Matthew Morris, Dr Jo Appleby, Prof Sarah Hainsworth, and Dr Turi King, with whom I worked most closely on the genetic aspects of the project. Others from outside of Leicester also made major contributions (see publications for details) but, with reference to this talk, thanks are due to Bob Woosnam-Savage of the Royal Armouries, Leeds, who provided expertise on the weapons which may have killed Richard. Special acknowledgement is due to Philippa Langley, without whom none of this would have happened, for it was she who chased and lobbied the City Council to grant permission for the dig to go ahead and persuaded Richard Buckley of the University of Leicester Archaeological Service that it was worth undertaking. -

Richard III: the Sources What Did We Know When?

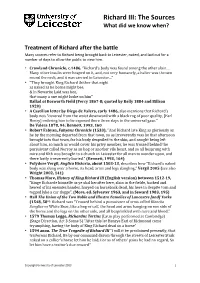

Richard III: The Sources What did we know when? Treatment of Richard after the battle Many sources refer to Richard being brought back to Leicester, naked, and laid out for a number of days to allow the public to view him. • Crowland Chronicle, c.1486, “Richard’s body was found among the other slain.... Many other insults were heaped on it, and, not very humanely, a halter was thrown round the neck, and it was carried to Leicester...” • ‘‘They brought King Richard thither that night as naked as he borne might bee. & in Newarke Laid was hee, that many a one might looke on him” Ballad of Bosworth Field (Percy 1867-8; quoted by Kelly 1884 and Billson 1920) • A Castilian letter by Diego de Valera, early 1486, also mentions that Richard’s body was “covered from the waist downward with a black rag of poor quality, [Earl Henry] ordering him to be exposed there three days to the universal gaze.” De Valera 1878, 94; Bennett, 1993, 160 • Robert Fabyan, Fabyans Chronicle (1533), “And Richard late King as gloriously as he by the morning departed from that town, so as irreverently was he that afternoon brought into that town, for his body despoiled to the skin, and nought being left about him, so much as would cover his privy member, he was trussed behind the pursuivant called Norroy as an hog or another vile beast, and so all besprung with mire and filth was brought to a church in Leicester for all men to wonder upon, and there lastly irreverently buried.” (Bennett, 1993, 164) • Polydore Vergil, Anglica Historia, about 1503-13, describes how “Richard’s naked body was slung over a horse, its head, arms and legs dangling,” Vergil 2005 (see also Wright 2002, 141) • Thomas More, History of King Richard III (English version) between 1512-19, “Kinge Richarde himselfe as ye shal herafter here, slain in the fielde, hacked and hewed of his enemies handes, haryed on horseback dead, his here in despite torn and togged lyke a cur dogge”. -

Ricardian Register

Ricardian Register Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 43 No. 2 June, 2012 Richard III and Francis, Viscount Lovel, riding through Oxford. Mary Kelly Printed with permission l White Boar l Copyright © Mary Kelly 2005 Articles: The College of Arms l Disinheritance l Thomas Stafford Inside cover (not printed) Contents The College of Arms 2 Disinheritance: 4 Thomas Stafford—16th Century Yorkist Rebel 7 Reviews 10 Behind the Scenes 18 In Memoriam: Judith M. Betten 20 2012 AGM Brochure 21 American Branch Elections 26 Bylaws 28 Sales Catalog–June, 2012 29 From the Editor 34 Errata 34 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts 35 v v v ©2012 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical, electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval—without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 annually. In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch. The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Dues are $50 annually for U.S.