World Economic Survey 1985-1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvin Leath

B A Y L O R U N I V E R S I T Y C o l l e c t i o n s o f P o l i t i c a l M a t e r i a l s P a p e r s o f M A R V I N L E A T H P R E L I M I N A R Y I N V E N T O R Y Boxes sent from Washington: 1-67; 116-160. Boxes 68-115 presumed lost in transit in early 1991. B O X D e s c r i p t i o n Y e a r 1 Corr. Numbered files 8300 - 9199 Dec. 1981 - Feb. 1982 2 Corr. Numbered files 9200 - 9999 Feb. 1982 – Mar. 1982 3 Corr. Numbered files 10000 – 10799 Mar. 1982 4 Corr. Numbered files 10800 – 11699 Mar. 1982 – Apr. 1982 5 Corr. Numbered files 11700 – 12299 Apr. 1982 - May 1982 6 Corr. Numbered files 12300 – 12999 May 1982 7 Corr. Numbered files 13000 – 13699 May 1982 – June 1982 8 Corr. Numbered files 13700 – 14399 June 1982 – July 1982 9 Corr. Numbered files 14400 – 15099 July 1982 – Aug. 1982 1 0 Corr. Numbered files 15100 – 15799 Aug. 1982 – Sept. 1982 1 1 Corr. Numbered files 15800 – 16399 Sept. 1982 – Nov. 1982 1 2 Corr. Numbered files 16400 – 17199 Nov. 1982 – Dec. 1982 1 3 Corr. Numbered files 17200 – 17462 Jan. 1983 1 4 Corr. Numbered files 14475 – 17690 + forms Jan. 1983 1 5 Corr. -

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Jan 1963 $17,200 (NA) Feb 1963 $17,700 (NA) Mar 1963 $18,200 (NA) Apr 1963 $18,200 (NA) May 1963 $17,500 (NA) Jun 1963 $18,000 (NA) Jul 1963 $18,400 (NA) Aug 1963 $17,800 (NA) Sep 1963 $17,900 (NA) Oct 1963 $17,600 (NA) Nov 1963 $18,400 (NA) Dec 1963 $18,700 (NA) Jan 1964 $17,800 (NA) Feb 1964 $18,000 (NA) Mar 1964 $19,000 (NA) Apr 1964 $18,800 (NA) May 1964 $19,300 (NA) Jun 1964 $18,800 (NA) Jul 1964 $19,100 (NA) Aug 1964 $18,900 (NA) Sep 1964 $18,900 (NA) Oct 1964 $18,900 (NA) Nov 1964 $19,300 (NA) Dec 1964 $21,000 (NA) Jan 1965 $20,700 (NA) Feb 1965 $20,400 (NA) Mar 1965 $19,800 (NA) Apr 1965 $19,900 (NA) May 1965 $19,600 (NA) Jun 1965 $19,800 (NA) Jul 1965 $21,000 (NA) Aug 1965 $20,200 (NA) Sep 1965 $19,600 (NA) Oct 1965 $19,900 (NA) Nov 1965 $20,600 (NA) Dec 1965 $20,300 (NA) Jan 1966 $21,200 (NA) Feb 1966 $20,900 (NA) Mar 1966 $20,800 (NA) Apr 1966 $23,000 (NA) May 1966 $22,300 (NA) Jun 1966 $21,200 (NA) Jul 1966 $21,800 (NA) Aug 1966 $20,700 (NA) Sep 1966 $22,200 (NA) Oct 1966 $20,800 (NA) Nov 1966 $21,700 (NA) Dec 1966 $21,700 (NA) Jan 1967 $22,200 (NA) Page 1 of 13 Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Feb 1967 $22,400 (NA) Mar 1967 $22,400 (NA) Apr 1967 $22,300 (NA) May 1967 $23,700 (NA) Jun 1967 $23,900 (NA) Jul 1967 $23,300 (NA) Aug 1967 $21,700 (NA) Sep 1967 $22,800 (NA) Oct 1967 $22,300 (NA) Nov 1967 $23,100 (NA) Dec 1967 $22,200 (NA) Jan 1968 $23,400 (NA) Feb 1968 $23,500 (NA) Mar 1968 -

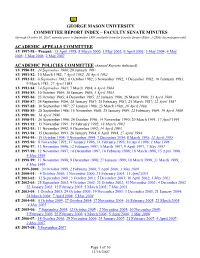

George Mason University Committee Report Index – Faculty Senate Minutes

GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY COMMITTEE REPORT INDEX – FACULTY SENATE MINUTES (through October 10, 2007; minutes prior to September 1994 available from the Faculty Senate Office, 3-2990; [email protected]) ACADEMIC APPEALS COMMITTEE AY 1997-98 – Present: 15 April 1998; 8 March 2000; 1 May 2002; 9 April 2003; 5 May 2004; 4 May 2005; 3 May 2006: 2 May 2007 ACADEMIC POLICIES COMMITTEE (Annual Reports italicized) AY 1980-81: 24 September 1980; 28 January 1981 AY 1981-82: 10 March 1982; 7 April 1982; 28 April 1982 AY 1982-83: 8 September 1982; 6 October 1982; 3 November 1982; 1 December 1982; 16 February 1983; 9 March 1983; 27 April 1983 AY 1983-84: 14 September 1983; 7 March 1984; 4 April 1984 AY 1984-85: 10 October 1984; 30 January 1985; 3 April 1985 AY 1985-86: 23 October 1985; 4 December 1985; 22 January 1986; 26 March 1986; 23 April 1986 AY 1986-87: 24 September 1986; 28 January 1987; 25 February 1987; 25 March 1987; 22 April 1987 AY 1987-88: 30 September 1987; 27 January 1988; 23 March 1988; 20 April 1988 AY 1988-89: 28 September 1988; 16 November 1988; 25 January 1989; 22 February 1989; 19 April 1989 AY 1989-90: 18 April 1990 AY 1990-91: 26 September 1990; 24 October 1990; 14 November 1990; 20 March 1991; 17 April 1991 AY 1991-92: 13 November 1991; 19 February 1992; 18 March 1992 AY 1992-93: 11 November 1992; 9 December 1992; 14 April 1993 AY 1993-94: 15 December 1993; 26 January 1994; 6 April 1994; 27 April 1994 AY 1994-95: 19 October 1994; 9 November 1994; 7 December 1994; 8 March 1995; 12 April 1995 AY 1995-96: 8 November 1995; 17 January -

The U.S. Automobile Industry: Monthly Report on Selected Economic Indicators

THE U.S. AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY: MONTHLY REPORT ON SELECTED ECONOMIC INDICATORS Report to the Subcommittee on Trade, Committee on Ways and Means, on Investigation No. 3 3 2-2 0 7 Under Section 3 3 2 of the Tariff Act of 1930 USITC PUBLICATION 185 3 MAY 1986 United States International Trade Commission I Washington, DC 20436 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Paula Stern, Chairwoman Susan W. Llebeler, Vice Chairman . Alfred E. Eckes Seeley G. Lodwick David B. Rohr Anne E. Brunsdale This report was prepared principally by Jim McElroy and Dennis Rapkins Machinery and Transportation Equipment Branch Machinery and Equipment Division · Off ice of Industries Erland Heginbotham, Director Address all communications to . Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary to the Com.mission United States International Trade Com.mission Washington, D.C 20436 C 0 N T E N T S Tables 1. New passenger automobiles: U.S. retail sales of domestic production, production, inventory, days' supply, and employment, by specified periods , May 19 8 4-Apri 1 19 86--·· .. ···:·-·--··-.. ·--·--·-·-----··-·-·-·---------·-··-'-·-.- .. ·--··-·-·------ 1 2. New passenger a1itomobiles: U.S. imports for consumption, by principal sources and by specified periods, April 1984- Ma re h 19 8 6 ... ·--····---.......... --... ·----···--···· .. -----··-·--.. ····-·---·-···· .. ··--·····-··-··· .. ·····-···-· .. ·-·---·-·· .. ·--............ -............ -.......... --····----· .. ·· ... ____ 2 3. Lightweight automobile trucks and bodies and cab/chassis for light weight automobile -

The U.S. Automobile Industry: Monthly Report on Selected Economic Indicators

THE U.S. AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY: MONTHLY REPORT ON SELECTED ECONOMIC INDICATORS Report to the Subcommittee on Trade, Committee on Ways and Means, on Investigation No.332-207 Under Section 332 of the Tariff. Act of 1930 USITC PUBLICATION 1739 AUGUST 1985 United States International Trade Commission / Washington, DC 20436 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Paula Stern, Chairwoman Susan W. Liebeler, Vice Chairman Alfred E. Eckes Seeley G. Lodwick David B. Rohr This report was prepared principally by Jim McElroy and John Creamer Machinery and Transportation Equipment Branch Machinery and Equipment Division Office of Industries Erland Heginbotham, Director Address all communications to Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 C ONTENTS Page Tables 1. New passenger automobiles: U.S. retail sales of domestic production, production, inventory, days' supply, and employment, by specified periods, August 1983—July 1985 1 2. New passenger automobiles: U.S. imports for consumption, by principal sources and by specified periods, July 1983—June 1985--•... 2 3. Lightweight automobile trucks and bodies and cab/chassis for light- weight automobile trucks: U.S. imports for consumption, by principal sources and by specified periods, July 1983—June 1985— . 3 4. New passenger automobiles: U.S. exports of domestic merchandise, by principal markets and by specified periods, July 1983— June 1985 4 5. Lightweight automobile trucks and bodies and cab/chassis for light- weight automobile trucks: U.S. exports of domestic merchandise, by principal markets and by specified periods, July 1983— June 1985 5 6. New passenger automobiles: Sales of domestic and imported passenger automobiles and sales of imported passenger automobiles as a percent of total U.S. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

Hickman County (Page 1 of 13) Office: Chancery Court

Hickman County (Page 1 of 13) Office: Chancery Court Type of Record Vol Dates Roll Format Notes Enrollments 1 Jun 1853 - May 1875 1 35mm Minutes A-C Sep 1854 - Mar 1873 2 35mm Minutes D Mar 1872 - Mar 1882 3 35mm Minutes F-G Sep 1882 - Mar 1893 4 35mm Minutes H Mar 1895 - Feb 1902 5 35mm Minutes I-J Feb 1902 - Apr 1919 A-247 35mm Minutes K-L Jul 1919 - Jul 1931 A-248 35mm Minutes M-N Jul 1931 - Jul 1942 A-249 35mm Minutes O-P Jul 1942 - Mar 1957 A-250 35mm Minutes Q-T Apr 1957 - Jan 1982 A-10,146 16mm Minutes U-Z Jan 1982 - Jan 1987 A-10,147 16mm Minutes A1-E1 Jan 1987 - Feb 1990 A-10,148 16mm Minutes F1-H1 Feb 1990 - Aug 1992 A-10,149 16mm Minutes I1-K1 Aug 1992 - Aug 1994 A-10,150 16mm Hickman County (Page 2 of 13) Office: Circuit Court Type of Record Vol Dates Roll Format Notes Minutes Nov 1841 - Mar 1853 A-252 35mm Minutes A Jan 1847 - Feb 1869 6 35mm Minutes C-D Sep 1874 - Jun 1887 7 35mm Minutes E-F Oct 1887 - Jun 1895 8 35mm Minutes 1-2 Oct 1895 - Mar 1905 A-253 35mm Minutes 3-4 Sep 1905 - Dec 1916 A-254 35mm Minutes 5-6 Dec 1916 - Aug 1926 A-255 35mm Minutes 7-8 Aug 1926 - Sep 1940 A-256 35mm Minutes 9-10 Nov 1940 - Nov 1954 A-257 35mm Minutes, Civil 11-15 Mar 1955 - Jun 1978 A-10,154 16mm Minutes, Civil 16-20 Jun 1978 - May 1983 A-10,155 16mm Minutes, Civil 21-25 May 1983 - Dec 1987 A-10,156 16mm Minutes, Civil 26-29 Dec 1987 - Jan 1994 A-10,157 16mm Minutes, Criminal Jan 1908 - May 1911 A-258 35mm Minutes, Criminal 1-5 Mar 1955 - Jul 1973 A-10,158 16mm Minutes, Criminal 6-10 Aug 1973 - Aug 1977 A-10,159 16mm Minutes, Criminal -

Resource Law Notes Newsletter, No. 5, May 1985

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Resource Law Notes: The Newsletter of the Natural Resources Law Center (1984-2002) Newsletters 5-1985 Resource Law Notes Newsletter, no. 5, May 1985 University of Colorado Boulder. Natural Resources Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/resource_law_notes Part of the Energy and Utilities Law Commons, Energy Policy Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons, Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons, Public Policy Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information Resource Law Notes: The Newsletter of the Natural Resources Law Center, no. 5, May 1985 (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law). RESOURCE LAW NOTES: THE NEWSLETTER OF THE NATURAL RESOURCES LAW CENTER, no. 5, May 1985 (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law). Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. Resource Law Notes The Newsletter of the Natural Resources Law Center University of Colorado, Boulder • School of Law Number 5, May 1985 Two Conferences 11:15 a.m. Lawrence J. MacDonnell, The Endangered Species Act and Western Water Scheduled for June Development As part of its sixth annual summer program, the Natural 12:00 noon David Getches, The Future of Western Resources Law Center is presenting two conferences. -

Quantitative Methods (Geography 441) Name: ______SPSS 9: Time Series Dr

Quantitative Methods (Geography 441) Name: ______________________________ SPSS 9: Time Series Dr. Paul Marr Please complete the following exercise using the data below and include a sheet showing your work and results. This sheet MUST be typed using the exercise answer format. Below are the dates and atmospheric CO2 readings from the Mona Loa observatory, Hawaii for the years 1981 - 1985. Please decompose these data into seasonal, trend, and error components using a span of 12. Using these decomposed data, please develop the following graphics: 1. A line graph of the original CO2 concentration over the 5-year period. 2. A line graph of the seasonal component over the 5-year period. 3. A line graph of the CO2 trend over the 5-year period. 4. A bar graph of the error over the 5-year period. Finally, determine if there is a significant trend in CO2 concentrations and predict the trend concentration in Dec 1990. Remember there are 3155760 seconds per year… Double points will be earned if you can add this value and produce a new line graph accurately showing your prediction within the trend series. Date CO2 Date CO2 Date CO2 Date CO2 Date CO2 Jan 1981 339.36 Jan 1982 340.92 Jan 1983 341.64 Jan 1984 344.05 Jan 1985 345.25 Feb 1981 340.51 Feb 1982 341.69 Feb 1983 342.87 Feb 1984 344.77 Feb 1985 346.06 Mar 1981 341.57 Mar 1982 342.85 Mar 1983 343.59 Mar 1984 345.46 Mar 1985 347.66 Apr 1981 342.56 Apr 1982 343.92 Apr 1983 345.25 Apr 1984 346.77 Apr 1985 348.20 May 1981 343.01 May 1982 344.67 May 1983 345.96 May 1984 347.55 May 1985 348.92 Jun -

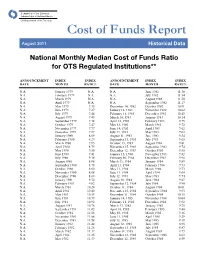

Historical Data

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report August 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A. -

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Council Distr. GENERAL E

UNITED E NATIONS Economic and Social Council Distr. GENERAL E/RES/1987/31 14th Plenary Meeting 26 May 1987 1987/31. Demand and supply of opiates for medical and scientific needs The Economic and Social Council, Recalling its resolutions 1979/8 of 9 May 1979, 1980/ 20 of 30 April 1980, 1981/8 of 6 May 1981, 1982/12 of 30 April 1982, 1983/3 of 24 May 1983, 1984/21 of 24 May 1984, 1985/16 of 28 May 1985 and 1986/9 of 21 May 1986, Bearing in mind the supplement to the report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 1980 on demand and supply of opiates for medical and scientific needs38/ and the recommendations contained therein, as well as the special report on the same subject prepared by the Board in 1985,39/ Having considered the report of the Board for 1986,36/ in particular paragraph 38 to 42 on the demand for and supply of opiates for medical and scientific purposes, as well as the report of the Board on statistics on narcotic drugs for 1985,40/ Noting that the Board again reports that supply and demand are in approximate balance, Noting with concern that the Board has been provided with insufficient resources, and that this affects the priority given to the implementation of the request of the Council contained in its resolution 1986/9, Bearing in mind the burden already borne by the traditional supplier countries faced with the question of excessive stocks of raw materials, Reaffirming the fundamental need for international cooperation and solidarity in the effort, consistent with the relevant provisions of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, to maintain a balance between legitimate supply and demand of opiates and in overcoming the problem of excessive stocks, 1. -

Fayette County (Page 1 of 22) Office: Chancery Court

Fayette County (Page 1 of 22) Office: Chancery Court Type of Record Vol Dates Roll Format Notes Minutes S-T May 1925 - Nov 1940 A-3090 35mm Minutes U-V Nov 1940 - May 1956 A-3091 35mm Minutes W-Z May 1956 - May 1976 A-11,625 16mm Minutes 1-3 May 1976 - May 1979 A-11,626 16mm Minutes 4-6 May 1979 - Oct 1980 A-11,627 16mm Minutes 7-9 Oct 1980 - Nov 1981 A-11,628 16mm Minutes 10-12 Nov 1981 - May 1983 A-11,629 16mm Minutes 13-15 May 1983 - May 1985 A-11,630 16mm Minutes 16-18 May 1985 - Jan 1987 A-11,631 16mm Minutes 19-21 Jan 1987 - Sep 1988 A-11,632 16mm Minutes 22-24 Sep 1988 - Feb 1990 A-11,633 16mm Minutes 25-27 Feb 1990 - Jun 1991 A-11,634 16mm Minutes 28-30 Jun 1991 - Jun 1992 A-11,635 16mm Minutes 31-33 Jun 1992 - Apr 1993 A-11,636 16mm Minutes 34-36 Apr 1993 - Jan 1994 A-11,637 16mm Minutes 37-39 Jan 1994 - Oct 1994 A-11,638 16mm Minutes 40-41 Oct 1994 - Jun 1995 A-11,639 16mm Fayette County (Page 2 of 22) Office: Circuit Court Type of Record Vol Dates Roll Format Notes Minutes Jun 1829 - Jun 1832 1 35mm Minutes Dec 1832 - May 1836 1A 35mm Minutes G-H Sep 1842 - Feb 1851 1 35mm Minutes Oct 1858 - Jun 1860 8 35mm Minutes I-J Jun 1859 - Nov 1867 2 35mm Minutes K-L Mar 1868 - Jul 1871 3 35mm Minutes M-N Oct 1871 - Nov 1874 4 35mm Minutes O-P Feb 1875 - Aug 1877 5 35mm Minutes Q-R Oct 1877 - Feb 1880 6 35mm Minutes S-T Jun 1880 - Jul 1882 7 35mm Minutes U-V Oct 1882 - Oct 1885 8 35mm Minutes W-X Feb 1886 - Sep 1891 9 35mm Minutes Y-Z Jan 1892 - Sep 1900 10 35mm Minutes 27-28 Jan 1901 - Apr 1910 A-3092 35mm Minutes 29-30 Jul 1910 - Mar