Myth and Patriarchy in Deepa Mehta's Heaven on Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Feminine Eye: Lecture 5: WATER: 2006: 117M

1 The Feminine Eye: lecture 5: WATER: 2006: 117m: May 2: Women Directors from India: week #5 Mira Nair / Deepa Mehta Screening: WATER (Deepa Mehta, 2005) class business: last class: next week: 1. format 2. BEACHES OF AGNES 3. Fran Claggett 2 Women Directors from India: Mira Nair: [Ni-ar = liar] b. 1957: India: education: Delhi [Delly] University: India Harvard: US began film career as actor: then: directed docs 1988: debut feature: SALAAM BOMBAY! kids living on streets of Bombay: real homeless kids used won Camera d’Or: Cannes Film Festival: Best 1st Feature clip: SALAAM BOMBAY!: ch 2: 3m Nair’s stories: re marginalized people: films: focus on class / cultural differences 1991: MISSISSIPPI MASALA: interracial love story: set in US South: black man / Indian woman: Denzel Washington / Sarita Choudhury 2001: MONSOON WEDDING: India: preparations for arranged marriage: groom: Indian who’s relocated to US: Texas: comes back to India for wedding won Golden Lion: Venice FF 2004: VANITY FAIR: Thackeray novel: early 19th C England: woman’s story: Becky Sharp: Witherspoon 2006: THE NAMESAKE: story: couple emigrates from India to US 2 kids: born in US: problems of assimilation: old culture / new culture plot: interweaving old & new Nair: latest film: 2009: AMELIA story of strong pioneering female pilot: Swank 3 Deepa Mehta: b. 1950: Amritsar, India: father: film distributor: India: degree in philosophy: U of New Delhi 1973: immigrated to Canada: embarked on professional career in films: scriptwriter for kids’ movies Mehta: known for rich, complex -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : Promila Mehta, M.Sc, Ph.D. Designation : Professor Department : Human Genetics Date of Birth : 8th December 1953 Present work address : Professor, Department of Human Genetics, Punjabi University, Patiala Phones : 0175-3046277, 0175-3046278 Mobile : 09478258900 Email : [email protected] Area of specialization : Human Biochemical Genetics Academic Qualifications : M.Sc., M.Phil., Ph.D. Examination Board/University/ Year %age of Division Subjects Taken (Degree Institute Marks held) B.Sc. Punjabi University, 1972 57.4 IInd Botany, Zoology, Patiala Chemistry M.Sc. Punjabi University, 1974 55.4 IInd Human Biology Patiala M.Phil. Punjabi University, 1982 - Through Human Biology Patiala Research Ph.D. Punjabi University, 1985 A Study of Biological Markers in various Patiala Malignancies Any Other : B.Ed. Punjabi University, 1975 Patiala M.Ed. Punjabi University, 1977 Patiala Certificate course in Russian Language Brief Information Particulars/Events Numbers Research papers published 75 Books 3 Ph.D.'s guided and under guidance, respectively 5, 7 Research projects undertaken 1,2 Organized national conferences and refresher courses 10 Research and teaching experience in years, respectively 31 years 8 months Organized, participated and presented papers in National and 50 International Conferences Popular articles published in Punjabi 5 Attended Refresher Courses 4 Membership of academic and professional associations/bodies 9 Fellowships: Junior and Senior Research Fellow of ICMR, New Delhi (1981-85) Administrative -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

1 Professor Prageeta Sharma Film 381: Wednesday/Friday 10:40 Am-‐1:00Pm JRH

Professor Prageeta Sharma Film 381: Wednesday/Friday 10:40 am-1:00pm JRH 205 Office Hours: Thursday: 10am-12:30pm, LA 211 e-mail: [email protected] SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA AND TELEVISION: FROM THE APU TRILOGY TO SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE AND THE MINDY PROJECT. “When I Was groWing up in the nineties, no one on my favorite shoWs ever looked like me.” -- Manori Ravindran There's been a recent revolution in mainstream moviemaking and American and Canadian television (although, it has happened much earlier for BBC). Outside of Bollywood’s narrative formulas, more and more South Asians and South Asian descent actors are populating the film and television industry. In addition to acting, they are producing, directing, writing scripts, and creating their own television shoWs. Even so, it is still difficult to unpack the racial stereotypes of Indians from the subcontinent: Are they edgy characters or unsettling, exaggerated portraits inconsistent with reality? What are our narrative discourses around the subcontinent and South Asian immigrant culture? What has it looked like and What does the 21st century South Asian media culture outside of India Want to accomplish? This class Will explore the representations of South Asians in filmmaking and television from mid-twentieth century to the present day. We will Watch Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, several of Satyajit Ray's films and figure out hoW they differ from Merchant Ivory Productions. We Will discuss Peter Sellar’s character in The Party; We Will explore Hanif Kureishi's My Beautiful Laundrette, Jhumpa Lahiri & Mira Nair’s The Namesake, the Harold and Kumar trilogy and phenomenon, Gurinder Chadha’s Bend it Like Beckham, Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire, Salman Rushdie and Deepa Mehta’s Midnight Children, Umesh Shukla's Oh My God, and television shows and series like The Far Pavilions (1984), The Mindy Project, Parks and Recreation, Community, and The Good Wife to figure out the range in characters and over-arching themes for South-Asians today. -

Dinesh Mehta

DINESH MEHTA Professor Emeritus, School of Planning, 501 A, Shantanu Apartments CEPT University, University Road Azad Society, Ambawadi Ahmedabad, 380 009 AHMEDABAD 380 015 INDIA INDIA [email protected] , [email protected]; Tel: +91-79-26763175(h), cell +91-9898200148(m) Dinesh Mehta is a Professor Emeritus at CEPT University, Ahmedabad. He is currently engaged in a major research project on performance assessment of urban water and sanitation at CEPT University (see www.pas.org.in). Dr. Mehta has worked on urban policy, urban planning and management for over 40 years in Asia and Africa. He has been associated with CEPT since 1977, when he began his academic career as Assistant Professor at School of Planning, CEPT in 1977 and was the Director of the School of Planning during 1986- 1992. During 1992-97 Prof. Mehta was director of the National Institute of Urban Affairs, New Delhi, which is an autonomous undertaking of the Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. At NIUA he initiated many activities related to Urban Basic Services for the Poor (UBSP), the Indo-USAID Project (FIRE-D), and projects on environmental planning and urban governance. In 1997, Dr Mehta joined UN- HABITAT as the regional advisor for the Urban Management Programme and developed programme activities in South and East Asia. In 2000, Dr. Mehta moved to UN-HABITAT Nairobi, as the chief coordinator of the global Urban Management Programme which worked in over 50 countries in 150 cities in Asia, Africa, Arab states and Latin America. In 2007, Dr Mehta returned back to CEPT to pursue research and teaching activities. -

Bureaucrats and Movie Czars: Canada's Feature Film Policy Since

Media Industries 4.2 (2017) DOI: 10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.204 Bureaucrats and Movie Czars: Canada’s Feature Film Policy since 20001 Charles Tepperman2 UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY c.tepperman [AT] ucalgary.ca Abstract: This essay provides a case study of one nation’s efforts to defend its culture from the influx of Hollywood films through largely bureaucratic means and focused on the increasingly outdated metric of domestic box-office performance. Throughout the early 2000s, Canadian films accounted for only around 1 percent of Canada’s English-language market, and were seen by policy makers as a perpetual “problem” that needed to be fixed. Similar to challenges found in most film-producing countries, these issues were navigated very differently in Canada. This period saw the introduction of a new market-based but cultural “defense” oriented approach to Canadian film policy. Keywords: Film Policy, Production, Canada Introduction For over a century, nearly every film-producing nation has faced the challenge of competing with Hollywood for a share of its domestic box office. How to respond to the overwhelming flood of expensively produced and slickly marketed films that capture most of a nation’s eye- balls? One need not be a cultural elitist or anti-American to point out that the significant presence of Hollywood films (in most countries more than 80 percent) can severely restrict the range of films available and create barriers to the creation and dissemination of home- grown content.3 Diana Crane notes that even as individual nations employ cultural policies to develop their film industries, these efforts “do not provide the means for resisting American domination of the global film market.”4 In countries like Canada, where the government plays a significant role in supporting the domestic film industry, these challenges have political and Media Industries 4.2 (2017) policy implications. -

Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute Sponsored Multidisciplinary International Seminar Bollywood’S Soft Power

Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute sponsored Multidisciplinary International Seminar Bollywood’s Soft Power 13-15 December 2009 Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur West Bengal India 721 302 The Seminar is part of a two-year long collaborative project on Bollywood’s Role in Promoting India Canada Relations and is generously funded by the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute. Soft power, a term coined by the Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye in his book, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power(1990), which he developed a decade and a half later in Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics(2004) has entered the vocabulary of international relations over the years. By soft power Nye means “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than through coercion” and believes that soft power enables a nation "to achieve desired outcomes in international affairs through attraction rather than coercion." It was Nye who made the connection between Bollywood and soft power when he asserted that “Indian films with a sprawling audience across Asia, Middle East and Africa, are the cutting edge of the country's soft power” at the Davos Meet in January 2006. Two years later, author, peacekeeper and politician Shashi Tharoor seconded him by citing the international popularity of Bollywood films as an example of India’s rising soft power. But when the Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh recently told a group of IAS probationers that “cultural relations, India's film industry, Bollywood...I find wherever I go in the Middle East, in Africa, people talk about Indian films," and underlined the need to put soft power to use as an important instrument of foreign policy, Bollywood’s soft power received official recognition. -

57C42f93a2aaa-1295988-Sample.Pdf

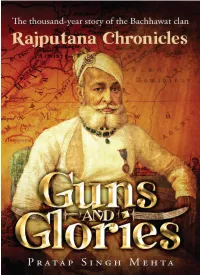

Notion Press Old No. 38, New No. 6 McNichols Road, Chetpet Chennai - 600 031 First Published by Notion Press 2016 Copyright © Pratap Singh Mehta 2016 All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-93-5206-600-1 This book has been published in good faith that the work of the author is original. All efforts have been taken to make the material error-free. However, the author and the publisher disclaim the responsibility. No part of this book may be used, reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The information regarding genealogy of Deora Chauhans and Bachhawat Mehtas, available from different books of history, internet, “Bhaats” (story tellers) and inscriptions, is full of contradictions and the names are at variance. The history of any person or place is also the perception and objective of the writer. However, care has been taken to present the paper factually and truly after due moderation. Therefore, the author and publisher of this book are not responsible for any objections or contradictions raised. Cover Credits: Painting of Mehta Rai Pannalal: Raja Ravi Varma (Travancore), 1901 Custodian of Painting: Ashok Mehta (New Delhi) Photo credit: Ravi Dhingra (New Delhi) Contents Foreword xi Preface xiii Acknowledgements xvii Introduction xix 1.1 Genealogy of Songara and Deora Chauhans in Mewar 4 1.2 History – Temple Town of Delwara (Mewar) 7 Chapter 1.3 Rulers of Delwara 10 12th–15th 1.4 Raja Bohitya Inspired by Jain Philosophy 11 Century -

Canadian Films: What Are We to Make of Them?

Canadian Films: What Are We to Make of Them? By Gerald Pratley Spring 1998 Issue of KINEMA This technically fine picture was shot in British Columbia, but care seems to have been taken toeradicate any sign of Canadian identity in the story’s setting, which is simply generic North American. Film critic Derek Elley in his review of Mina Shum’s Drive, She Said in Variety, Dec. 22, 1997. NO MATTER to what segment of society individuals may belong within the public at large most of those interested in the arts are contemplating what to make of Canadian cinema. Among indigent artists, out- of-work actors, struggling writers, publishers and bookshop proprietors, theatregoers and movie enthusiasts, the question being asked is, what do we expect from Canadian movies? The puzzle begins when audiences, after being subjected to a barrage of media publicity and a frenzy of flag waving, which would have us believe that Canadian movies and tv programmes are among the best in the world, discover they are mostly embarrassingly bad. Except that is, films made in Québec. Yet even here the decline into worthlessness over the past twoyears has become apparent. It is noticeable that, when the media in the provinces other than Québec talk about Canadian films, they are seldom thinking of those in French. This means that we are forced, whentalking about Canadian cinema, into a form of separation because Québec film making is so different from ”ours”, making it impossible to generalize over Canadian cinema as a whole. If we are to believe everything the media tells us then David Cronenberg, whose work is morbid, Atom Egoyan, whose dabblings leave much to be desired, Guy Maddin, who is lost in his own dreams, and Patricia Rozema, who seldom seems to know what she is doing, are among the world’s leading filmmakers. -

Dr. Rajendra Mehta –Detailed C.V

Dr. Rajendra Mehta –detailed C.V. Title Dr. First Rajendra Last Mehta Photograph Name Name Designation Assistant professor-Gujarati Address Department of modern Indian languages and literary studies, tutorial building, University of Delhi, Delhi -110007. Phone No Office 011-27666626 Mobile 9718475928 Email darvesh18@yahoo. com , [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. (Modern Gujarati Drama) Bhavnagar University, 1999 Gujarat. PG MA (Gujarati Language and Literature), 1992 Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. UG BA (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar 1990 University, Gujarat. Career Profile 2008- till date: Assistant Professor (Gujarati), University of Delhi, Delhi. 1992- 2008: Lecturer (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. Teaching and research experience of 19 years Areas of Interest / Specialization 1 Indian Drama and Theatre, comparative Indian literature, translation studies, translations into Indian languages, postmodernism and post colonialism theories in Indian literature. Subjects Taught 1- Gujarati language courses 2-M.A (Comparative Indian Literature) Theory of literary influence, Modernism, Postmodernism and Post- colonialism in Indian Theatre 3-M.Phil (Comparative Indian Literature): Gandhi in Indian literature. Research Guidance M.Phil. student -4 Ph.D. student 5 Publications Profile Books authored Mehta, Rajendra. 2010. vachyopasana (Collection Of Critical Essays). Ahmedabad: rannade prakashan Mehta, Rajendra. 2009. Sootrabadhha (Collection Of Critical Essays). Ahmedabad: Parshv Publications. Mehta, Rajendra. 2009. Nandivak (Collection Of Critical Essays). Ahmedabad: Parshv Publications. Mehta, Rajendra. 2009. Brahmlipi (Collection Of Critical Essays). Ahmedabad: Parshv Publications. Mehta, Rajendra. 2008. Brahmpalash (Collection Of Critical Essays). Ahmedabad: Parshv Publications. Mehta, Rajendra. 2008. Brahmvakya (Collection Of Critical Essays). Ahmedabad: Parshv Publications. Mehta, Rajendra. 2004. Natyarag (Collection Of Critical Essays). -

Dr. Sridhar Rajeswaran's Report

Trust Registration Number E/2423/Kachchh _____________________________________________________________________________________ Report on Field Visit to CICS, University of the Fraser Valley May 2014 I was awarded the South Asian Diaspora Fund grant by the Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies, University of Mumbai and the Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies, University of the Fraser Valley, in 2013-14 for my research project on the works of the Indo-Canadian Film maker Deepa Mehta. My main objective for this project was to focus on the Re-Imaging of the Nation in Mehta’s Elements Trilogy, Earth, Fire and Water. The purpose of the field visit to the CICS at the University of the Fraser Valley was to - 1. Contextualize the film maker in her diasporic geopolitical space of Canada 2. To get viewer response from Indo-Canadians on the stance adopted by Mehta in her films 3. To meet Mehta and interview her on the main objectives and metaphors in her films related to re- imaging the nation 4. To share my work and findings on Mehta’s films with the faculty, students and Indo-Canadian community members at the UFV My visit to the CICS even though it was very brief enabled me to interact with the dynamic Director of the Centre, Dr. Satwinder Bains and her committed team of researchers. I was also able to speak on Mehta’s films at the symposium organized by Dr. Bains and interact with the audience after the talk. I was also happy to meet the President of the UFV and realize the extent of his involvement with the CICS and his commitment to research on the Indo-Canadian community. -

Longfellow-22Bollywoodtoronto22.Pdf

My study of the exhibition and consumption of Bollywood films in Toronto is inspired by two key theoretical objects. The first has to do with the desire to explore alternatives to thinking globalization as a single integrated or unified conceptual scheme, a particular danger in Canadian studies where the tendency has been to read globalization exclusively as an extension of American cultural and economic imperialism. A more productive line of inquiry has been suggested by Saskia Sassen, who shifts the focus from the conventional globallnational axis to a consideration of how globalization is actualized in concrete localized forms at the sub-national level of cities. Of great import to the Canadian experience, Sassen insists that the presence of large diasporic populations in major metropolitan cities attests to the living reality of postcoloniality and uneven development, both historic features of long term global economies. As such, she argues, immigration and ethnicity need to be taken out of the paradigm of "otherness" and situated, precisely, as a fundamental aspect of globalization, "a set of processes whereby global elements are localized, international labour markets are constituted, and cultures from all over the world are de- and reterritorialized."' Introducing sub-national groupings like cities into an analysis of globalization, not only adds concrete specificity but allows for a consideration of the way in which economic globalization impacts on the lives of marginal subjects, "women, immigrants, people of colour; as she puts