Organic Farmers and Farms in Gujarat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Website Upload

ADVANCED ENZYME TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED Statement or information of unclaimed and unpaid dividend amounts of the Company separately for each of the previous seven financial years as on March 31, 2019 pursuant to the provisions of the Companies Act 2013 read with the Investor Education and Protection Fund Authority (Accounting, Audit, Transfer and Refund) Rules, 2016 (as amended effective from August 20, 2019) Pursuant to the provisions of Section 125(2) and other applicable provisions of the Companies Act, 2013 read with Investor Education and Protection Fund Authority (Accounting, Audit, Transfer and Refund) Rules, 2016 (as amended effective from August 20, 2019) dividend which remains unpaid or unclaimed for a period of seven years from the date of its transfer to unpaid dividend account is required to be transferred by the Company to Investor Education and Protection Fund (IEPF), established by the Central Government under the provisions of Section 125 of the Companies Act, 2013. Further the said details of unpaid/unclaimed dividend amounts as on the date of closure of financial year the account of which are to be adopted in the Annual General Meeting have to be identified by the Company and uploaded on the website of the Company. The said details of unpaid/unclaimed dividend accounts for seven year period identified by the Company as on March 31, 2019 is provided hereinafter. The shareholders who have not received and/or encashed their dividend warrants for the said financial years are requested to claim their respective unpaid/unclaimed dividend, if any, on or before the Proposed Date of transfer to IEPF, as mentioned herein after, unless you have already received the credit in your Bank account or have already encashed the dividend warrants. -

Pression from a William Shakespeare Play Used to Convey That Even the Meekest Or Most Docile of Creatures Will Retaliate Or Get Revenge If Pushed Too Far

THE WORM IS TURNING A documentary film by Hilary Bain and Åsa Mark Total run time 103 min • Aspect ratio: widescreen • DVD video Website and Trailer: thewormisturning.com Publicity contact: [email protected] + 1510-408-9892 [USA] + 612-8006-1705 [Australia] THE WORM IS TURNING starts in Punjab, India. After 40 years of chemical agriculture introduced as the Green Revolution, we see a dying, poisoned land: there are fields as far as the eye can see of dead soil, no trees, no birds, no insects, and polluted water and air. “Chemical farming is a system of killing all other life, to aid the growth of one single plant.” 2 Dr Amar Singh Azad, a pediatrician and community health specialist says; ”The toxins have penetrated so deep that they are affecting every aspect of life. We are already in the very active process of slow death. And this phenomenon is happening in other parts of the world also but in Punjab particularly, it’s very intense, very intense!” A train that leaves every evening from Bathinda nick-named the “cancer train". It carries patients to Bikaner Rajasthan as there is no free treatment in Punjab. 3 PUSHING PEOPLE OFF THE LAND The plan is to continue the corporatization of agriculture in India by eliminating most of India's farmers, there are 600 million still on the land, by making them corporate farm labor, or pushing them into cities, as was done America after World War 2. 4 THE EFFICIENCY MYTH “Our agricultural systems have developed in ways that have increased, very significantly the dependency of farming on fossil energy.” says Olivier De Schutter, former Special UN Rapporteur on the Right to Food. -

Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Limited Name Designation Department Email-Id Contact No Mr

Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Limited Name Designation Department email-id Contact No Mr. Rajesh Manjhu,IAS Managing Director Corporate Office [email protected] 0265-2356824 Mr. K R Shah Sr. Chief General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200651 Mr. THAKORPRASAD CHANDULAL CHOKSHI Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879202415 Mr. K N Parikh Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200737 Mr. Mayank G Pandya General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200689 Mr. KETAN M ANTANI Company Secretary Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200693 Mr. H R Shah Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208253 Mr. M T Sanghada Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208277 Mr. P R RANPARA Additional General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9825083901 Mr. V B Gandhi Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208141 Mr. BHARAT J UPADHYAY Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208224 Mr. S J Shukla Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200911 Mr. M M Acharya Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208282 Mr. Chandrakant N Pendor Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208799 Mr. Jatin Jayantilal Parikh Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200639 Mr. BIHAG C MAJMUDAR Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925209512 Mr. Paresh Narendraray Shah Chief Finance Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9825603164 Mr. Harsad Maganbhai Patel Controller of Accounts Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208189 Mr. H. I. PATEL Deputy General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200749 Mr. -

South Zone Drawing Section -- Date: 10-10-2018

TO AHMEDABAD TO TO GODHARA NATIONAL HIGHWAY NO. 8 DUMAL TO AHMEDABAD TO GUJARAT FARTILIZER TO SAVLI NORTH DUMAD CHOWKDI CHHANI VEMALI SARDAR CHOK. NATIONALDENA HIGHWAY NO. 8 "A" TO GODHARA START POINT OF RUT-5 REFINERY TOWNSHIP RAMAKAKA GOLDAN CHOWKDI DEARI N A R M A D A C A N A L PRAMUKH SQ. RAJESHWAR HARMONY AMBIKA SOC. SUNDER VAN MOTNATH MAHADEV NAVRACHNA SOC. RAJESHWAR GOLD AKAS GANGA AKAS START POINT:-RUT-6 VEGETABLE & GRAIN MARKET N.T.S Trimurti KARODIYA AVANTISOC. HARANI 10 HANUMAN NARMADA KAILAS MAHADEV. TEMP. TALAV VASAHAT CHANAKYA SAMA UNDERA Abhilasha Sainik sport 24.0 M. JALARAM TEMPLE MOTIBHAI chhatralay complex E.M.E CIRCLE HIGH WAY BY PASS 100.0 M. METRO ROAD 24.0M. Transportnagar 24.0 M. 18.0 M. NAVARACHNA NANUBHAI TOWER SCHOOL 30.0 M. 12 MAHESANA Panchavati DARJIPURA ROAD 24.0 M. CIRCLE Mehsana nagar MANGAL PANDEY RD. D-CABIN SAYAJIPURA AIRPORT TOWN HALL TO AJWA Delux KANHA RESI 18.0 M. 7 MUKHI NGR.TRAN RASTA MANEKPARK AJWA O.H.TANK CROSS RD. Amitnagar Soc. KALPANA NEW V.I.P. ROAD CANTONMENT V.I.P. ROAD SOCIETY 40.0 M. GORWA 40.0 M. S.R.Petrol Pump LAXMI STUDIO NIZAMPURA HANUMAN START POINT:-RUT-1 Ghelani Petrol Pump TEMP. LAXMIPURA KHODIYARNAGAR 18.0 M. "T" "C" VUDA END POINT:-RUT-6 WARD NO:2 20.0M. BHAVAN 36.0 M. 20.0 M. 30.0 M. 14 HARANI ROAD WARD:7 OFFICE 9 Nagar Anand END POINT OF RUT-5 SANGAM END POINT:-RUT-1 C.K PRAJAPATI SCHOOL Fateganj Circle 36.0 CROSS RD. -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Third International Conference in India-1102007

IDCA Conference on Sustainable Development in India, a Resounding Success New Delhi: On January 10, several dedicated social scientists and technologists, in the fields of sustainable livelihoods, healthcare, water and education came together to share and explore ways of helping lift India’s over 650,000 villages from their poverty. The conference entitled “Empowering Grassroots for Sustainable Development in India”, was held at Punjab Haryana Delhi (PHD) Chamber of Commerce House in New Delhi. It was organized by India Development Coalition of America (IDCA) and co-sponsored by Education Promotion Society of India (EPSI). More than 125 people representing various organizations from many parts of India and several NRIs participated in the 12- hour long program. Both IDCA and EPSI are setting historic precedents in bringing together the finest minds and the highest ideals from the Diaspora as well as from within India herself. Welcoming the conference participants from throughout India, the U.S., England and other countries was IDCA’s President, Dr. Mohan Jain. EPSI’s Secretary General, Shri Manohar Chellani, introduced the co-sponsoring organization which in only eighteen months of existence has made great strides in living up to it’s name. EPSI has implemented programs, cut through government red tape and connected resources to projects throughout the country. Ms. Anjali Makhija, Group leader at the Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon, served as master of ceremony for this session. The morning plenary session included four distinguished keynote speakers. Professor P. V. Indiresan, former director of IIT Madras was honored as chief guest of the session. He spoke about PURA projects and proposed for developing transformative approaches for rural development. -

2021 Anjuman Final Ahewal

786/92 :YF5GF o 1997 ;BFJT o OZDFG GAJL C{ ;BFJT ACL:T SF V[S NZbT C[4 _;SL XFB[ HDLG 5Z h]SL C]. C{4 _; G[ >; SL SL;L XFB SF[ YFD ,LIF4 JF[ >;[ HgGT D[\ ,[ HFI[\U[[P V\H]DG[ lZOF> R[ZL8[A, 8=:8 AL,LDF[ZFP Z_:80” 8=:8 G\AZ o JSOí))!í!((( GJ;FZL UF{Q[ VFhD V[HI]S[XG, V[g0 NLGL TF,LD tYF bJFhF UZLA GJFh D[0LS, ZL,LO O\0 JFlQ”S VC[JF, VG[ lZ5F[8” JQ” o Z)Z) < Z)Z! Our Website : www.Anjuman-e-Refai.org. <o 5|l;wW STF” o< CF_ VaN],CDLN _P D]ÿ,F\ CF_ ;],[DFGEF> V[;P 58[, CF_ VÿTFOC]X[G >A|FCLD Z[\8LIF CF_ DF[C\DN >SAF, V[P SF[,LIF DF[>GAFAF D]:TFS RZLJF,F ANJUMAN-E- REFAI CHERITABLE TRUST-BILIMORA Trustee Board No. Name Address Photo 1 Haji Abdul Hamid Haji GulamMohammed Mulla Station Road, Near by Station Masjid, Trustee Bilimora - 396 321 PhonePhone : 285444 Mo. : 9904278692 2 Haji Suleman Saleh Patel Sanket Appartment, Trustee M. G. Road, Bilimora - 396 321 Phone : 286344 Mo. : 9426889300 3 Haji Mohammed Iqbal Jawahar Road, Haji Ahmedbhai Koliya Again Post Office Trustee Bilimora - 396 321 Phone : 279786 Mo. : 9925555780 4 Haji AltafHusain Ibrahim 1072, Bangia Faliya, Rentia Bilimora - 396 321 Trustee Phone : 286137 Mo. : 9825119213 5 Moinbaba Mustak Chariwala 1072, Bangia Faliya, Trustee Bilimora - 396 321 Mo. : 9725586863 &*^Í(Z 8=:8GL :YF5GF !((& V\H]DG[ lZOF> R[ZL8[A, 8=:84 AL,LDF[ZF D[G[_\U 8=:8LGL S,D[YL V:;,FDF[ V,IS]D4 JPJP VÿCdN]l,ÿ,FCL ZaAL, VF,DLG J:;,FT] J:;,FD] V,F ;liINL, D]Z;,LGP ;J[” TFZLOG[ 5FShFT DF8[ K[4 H[6[ ;DU| ;’lq8G]\ ;H”G SI©] VG[ ,FBF[ SZF[0F[ N]~NF[< ;,FD < ;ZSFZ[<NF[<VF,D ;ÿ,FCF[ V,IC[ J:;,D 5Z H[DG[ Vÿ,FC TVF,FV[ -

ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 About the Organization This Logo Symbolizes the Objectives of the Organization

19th ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 About the organization This logo symbolizes the objectives of the organization. The words in the outer circle are from the great Indian epic "Mahabharat", saying that "nothing is above a Human". This is also the motto of the organization. The triangle in the inner circle symbolizes the hands of three people and stands for community development through participation. The light from the lamp in the small hut in the centre symbolizes the development of the weakest and poorest person of the community. Founder trustees of the organization were inspired by Gandhian thinking and work of great men like Albert Schweitzer. They felt deeply the agony and hopelessness of poor villagers. They saw the plight of villagers and felt a need of medical services in these villages. Hence they brought like minded friends together and founded Gram Seva Trust, an organization dedicated to rural health and development. In 1994 the trust started a 30 bedded hospital with 5 staff members in an old dilapidated building, given by another trust. As the need arose the hospital was expanded to accomodate more patients and better services. Today after 19 years the hospital can accomodate 80 patients and has all basic facilities required in a rural hospital providing health services at affordable rates and sometimes free of charge to the needy from nearly 200 surrounding villages of Navsari and Dang districts. The organization also wanted to improve health of the surrounding villages hence as and when need was identified different community projects were started in the surrounding villages with main focus on health and development of women and children. -

DTSI, Rajpipla

GUJARAT COUNCIL OF VOCATIONAL TRAINING 3rd floor, Block No. 8, Dr. Jivraj Mehta Bhavan Ghandhinagar Name of Exam 901 - Course on Computer Concept (CCC) Page no : 1 Center Name : 801 - DTSI RAJPIPLA Date of Exam 19/11/2008 Candidate Name and Designation Practical / Seat No Result Department Theory Marks Training Period Direct Exam 1 TADVI NARANBHAI JESANGBHAI Sr.No 22 34 ARM HEAD CONSTABLE 80190122022 12 Fail OFFICE OF THE SUPDTOF POLICE 2 PATEL MAHENDRAKUMAR VITTHALBHAI Sr.No 28 40 PRINCIPAL 80190122041 12 Fail SHREE VALLABH VIDYA NIKETAN BHADAM 3 PATEL DIVYANGKUMAR JAYANTILAL Sr.No 30 59 SATHI SAHAYAK 80190122042 29 Pass SHREE VALLABH VIDYA NIKETAN BHADAM 4 VASAVA HARIYABHAI CHIMANBHAI Sr.No 29 57 PEON 80190122043 28 Pass SHREE VALLABH VIDYA NIKETAN BHADAM 5 PATEL MRUDULABEN DINUBHAI Sr.No 27 57 SHIKSHAN SAHAYAK 80190122045 30 Pass SHREE VALLABH VIDYA NIKETAN BHADAM 6 ZALA JITENDRASINH UMEDSINH Sr.No 27 53 ASSISTANT TEACHER 80190122046 26 Pass SHREE VALLABH VIDYA NIKETAN BHADAM 7 ATODARIYA NILAMKUMARI TAKHATSINH Sr.No Ab 0 PRIMARY TEACHER 80190122047 Ab Absent SHREE ADARSH KUMAR SHALA 8 ROHIT VIPULBHAI CHANDUBHAI Sr.No Ab 0 PRIMARY TEACHER 80190122048 Ab Absent PRATHMIK SHALA KAPAT 9 VASAVA ANANDBHAI BHANGABHAI Sr.No 26 53 CRC CO ORDINATOR 80190122049 27 Pass PRATHMIK SHALA CHKDA 10 PRAJAPATI ISHWARBHAI RAYAJIBHAI Sr.No 28 49 TEACHER 80190122050 21 Fail DANDIA BAZAR MISHRA SHALA 11 CHAUHAN DAKXABEN RANJITSINH Sr.No 25 50 CLERK 80190122051 25 Pass COLLECTOR OFFICE 12 VASAVA RAJANBHAI DHIRUBHAI Sr.No 25 52 CLERK 80190122052 27 Pass COLLECTOR OFFICE, GUJARAT COUNCIL OF VOCATIONAL TRAINING 3rd floor, Block No. -

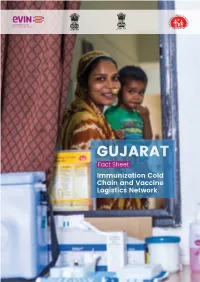

GUJARAT Fact Sheet Immunization Cold Chain and Vaccine Logistics Network

GUJARAT Fact Sheet Immunization Cold Chain and Vaccine Logistics Network 1 Gujarat Regional Vaccine 6 Stores District Vaccine 33 Stores The cold chain system in Gujarat consists of 4,083 working cold chain equipment. Corporation Vaccine 8 Stores 2 Walk-in Freezers Cold 9 Chain Walk-in 1,916 Points Coolers 2,142 Ice-Lined 51,602 Refrigerators Session Sites 1,930 Deep Freezers Sources of data: ॰ Live data from Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN), as accessed in July 2017. ॰ eVIN Preparatory Assessment Study, conducted by UNDP in year 2016, with updates provided by the state in 2017. 2 GUJARAT GujaratThe Universal Immunization Programme in Gujarat aims to immunize a target population of 13.2 lakh children and 14.5 lakh pregnant women, every year. The Electronic Vaccine Vaccine47 Cold1,916 Intelligence Network (eVIN) Store Chain Keepers Handlers has been implemented across all the vaccine stores The human resource network and cold chain points in to manage vaccine logistics in Gujarat. eVIN has facilitated Gujarat consists of 47 vaccine capacity-building of all store keepers and 1,916 cold vaccine store keepers and chain handlers, to manage the cold chain handlers in the vaccine logistics. They work state through 73 batches of under the guidance of the State training programmes on eVIN, Immunization Officer, District during the last two quarters of RCH Officers and Medical 2016. eVIN equipped them with Officers in-Charge. standardised stock registers and smartphones to digitise the vaccine stocks. The entire vaccine logistics data in Gujarat is now digitised and real-time data is available for informed decision-making. -

Population Structure and Genetic Bottleneck Analysis of Ankleshwar Poultry Breed by Microsatellite Markers

915 Population Structure and Genetic Bottleneck Analysis of Ankleshwar Poultry Breed by Microsatellite Markers A. K. Pandey*, Dinesh Kumar, Rekha Sharma, Uma Sharma, R. K. Vijh and S. P. S. Ahlawat National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, P. O. Box 129, Karnal-132 001, India ABSTRACT : Genetic variation at 25 microsatellite loci, population structure, and genetic bottleneck hypothesis were examined for Ankleshwar poultry population found in Gujrat, India. The estimates of genetic variability such as effective number of alleles and gene diversities revealed substantial genetic variation frequently displayed by microsatellite markers. The average polymorphism across the studied loci and the expected gene diversity in the population were 6.44 and 0.670±0.144, respectively. The population was observed to be significantly differentiated into different groups, and showed fairly high level of inbreeding (f = 0.240±0.052) and global heterozygote deficit. The bottleneck analysis indicated the absence of genetic bottleneck in the past. The study revealed that the Ankleshwar poultry breed needs appropriate genetic management for its conservation and improvement. The information generated in this study may further be utilized for studying differentiation and relationships among different Indian poultry breeds. (Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 2005. Vol 18, No. 7 : 915-921) Key Words : Ankleshwar, Bottleneck, Genetic Diversity, Microsatellites, Poultry INTRODUCTION these factors are operating, and present genetic information to be used in the conservation and improvement of this The ankleshwar poultry breed (Gallus gallus) is known unique poultry breed. to be a breed of Gujarat, India and its native tract is Of the many genetic markers now available, Bharuch (21.41 N latitude and 73.01 E longitude) and microsatellite loci are best suited for answering these Narmada districts (21.38 N latitude and 73.02 E longitude).