Universidad De Crdoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Join Us Poquitos, Served with a Side Salad and Dessert

Dine with an Angel In January, we hosted our Dine with an Angel Program. Chef Angel taught us how to make a traditional Mexican dish called Join us poquitos, served with a side salad and dessert. Poquitos are a deep fried tortilla filled with bacon, avocado, and shredded cheese, served with salsa and sour cream. After watching our V!VAfit Balance chefs demo on poquitos Community Members enjoyed some February 2020 Your V!VA Community Newsletter fine dining in the Craft Kitchen. Thank you Angel for providing us Advance Class with this wonderful learning opportunity and a delicious meal! Join us on the second floor Christmas Brunch for a a full 20 minute standing During this year’s Christmas celebration, Community Members welcomed their class in which we focus on families and friends into the Community to balance, strengthening and core share laughter, memories, and good wishes We will be using hand rails for while enjoying a classic holiday meal. The this class to keep us steady. Get scrumptious holiday brunch featured roast ready to sweat with your Lifestyles beef and salmon with all of the trimmings. Team Members and pick up some After lunch, Santa Claus made a surprise new workout tips! visit and took pictures with participants as they requested their most-wanted gifts for the season. A wonderful performance by the Quartet followed, getting everyone into the festive spirit! It was a warm and joyous Christmas wishes with Santa. Welcome Aprile time for all. This month we’re welcoming Aprile to our Lifestyles Team. She started out as a singer and moved into the field of recreation, completing a Recreation Therapy Diploma at Canadore College. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Beannachtaí Na Nollaigh Christmas Blessings by Mary Mcsweeney (See Page 3) Page 2 December 2010 BOSTON IRISH Reporter Worldwide At

December 2010 VOL. 21 #12 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2010 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Beannachtaí na Nollaigh Christmas Blessings by Mary McSweeney (See Page 3) Page 2 December 2010 BOSTON IRISH RePORTeR Worldwide at www.bostonirish.com John and Diddy Cullinane, and Gerard and Marilyn Doherty, Event Co-chairs Solas Awards Dinner Friday, December 10, 2010 Seaport Hotel, Boston Cash bar reception 5:30pm Dinner 6:30pm Seats are $200 each 2010 Solas Awardees Congressman Richard Neal Robert Glassman This year, the IIC is also pleased to introduce the Humanitarian Leadership award, honoring two exceptional people, who have contributed significantly to the recovery work in Haiti, following the devastating earthquake there. Please join us in honoring Sabine St. Lot, State Street Bank Corporation, and Marie St. Fleur, Director of Intergovernmental Relations, City of Boston Sponsorship opportunities are available for this event. If you or your organization would like to make a tax-deductible contribution to the Irish Immigration Center by sponsoring the Solas Awards Dinner, or you would like to attend the event, please call Mary Kerr, Solas Awards Dinner coordinator, at 617-695-1554 or e-mail her at [email protected]. We wish to thank our generous sponsors: The Law Offices of Gerard Doherty, Eastern Bank and Insurance, Wainwright Bank, State Street Corporation, Arbella Insurance Company, Carolyn Mugar, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, Michael Buckley Worldwide at www.bostonirish.com December 2010 BOSTON IRISH RePORTeR Page 3 ON THE TOWN WITH THE BIR American Ireland Fund Honors Hospice Founder More than 1,000 guests gathered at the Westin Bos- ton Waterfront on Nov. -

HELENA from the WEDDING Directed by Joseph Infantolino

HELENA FROM THE WEDDING Directed by Joseph Infantolino “Absorbing...deftly written and acted!” -- Jonathan Rosenbaum USA | 2010 | Comedy-Drama | In English | 89 min. | 16x9 | Dolby Digital Film Movement Press Contact: Claire Weingarten | 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B | New York, NY 10001 tel: (212) 941-7744 x 208 | fax: (212) 941-7812 | [email protected] Film Movement Theatrical Contact: Rebeca Conget | 109 W. 27th Street, Suite 9B | New York, NY 10001 tel: (212) 941-7744 x 213 | fax: (212) 941-7812 | [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS Newlyweds Alex (Lee Tergesen) and Alice (Melanie Lynskey) Javal are hosting a weekend-long New Year’s Eve party for their closest friends at a remote cabin in the mountains. They expect Alex’s best friend Nick (Paul Fitzgerald), newly separated from his wife, to show up at the cabin with his girlfriend Lola. Alex and Nick’s childhood friend Don (Dominic Fumasa) is also set to arrive with his wife-of-many-years Lynn (Jessica Hecht), as are Alice’s pregnant friend Eve (Dagmara Dominczyk) and her husband Steven (Corey Stoll) Any thoughts of a perfect weekend are quickly thrown out the window as Nick arrives with only a cooler of meat and the news that he and Lola have recently called it quits. Don and Lynn show up a few minutes later deep in an argument. Finally, Eve and Steven make it to the cabin with a surprise guest in tow—Eve’s friend Helena, who was a bridesmaid with Alice at Eve’s wedding. With tensions running high at the cabin, Alex tries to approach the young and beautiful Helena. -

Olivia Wilde

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Olivia Wilde Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company RICHARD JEWELL Kathy Scruggs Clint Eastwood Warner Bros LIFE ITSELF Abbey Dan Fogelman Amazon Studios LOVE THE COOPERS Eleanor Jessie Nelson CBS Films MEADOWLAND Sarah Reed Morano Bron Studios THE LAZARUS EFFECT Zoe David Gelb Relativity Studios BLACK DOG, RED DOG Sunshine Various RabbitBandini Productions THE LONGEST WEEK Beatrice Fairbanks Peter Glanz Armian Pictures Geoff Moore/David Occupant Entertainment/Altus BETTER LIVING THROUGH CHEMISTRY Elizabeth Roberts Posamentier Productions THIRD PERSON Anna Paul Haggis Corsan/Hwy61 HER Blind Date Spike Jonze Warner Bros RUSH Suzy Miller Ron Howard Universal DRINKING BUDDIES Kate Joe Swanberg Burn Later Productions THE INCREDIBLE BURT WONDERSTONE Jane Don Scardino New Line Cinema Brian Klugman/Lee THE WORDS Danielle Serena Films Sterthal PEOPLE LIKE US Hannah Alex Kurtzman DreamWorks DEADFALL Liza Stefan Ruzowitzky Magnolia Pictures ON THE INSIDE Mia Conlon D. W. Brown Mike Wittlin Productions IN TIME Rachel Salas Andrew Niccol Regency Enterprises BUTTER Brooke Swinkowski Jim Field Smith Vandalia Films THE CHANGE-UP Sabrina McArdle David Dobkin Big Kid Pictures COWBOYS AND ALIENS Ella Jon Favreau DreamWorks TRON: LEGACY Quorra Joseph Kosinski Disney THE NEXT THREE DAYS Nicole Paul -

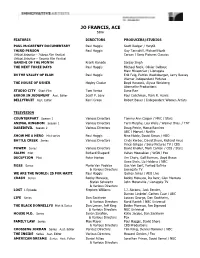

JO FRANCIS, ACE Editor

JO FRANCIS, ACE Editor FEATURES DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS PAUL McCARTNEY DOCUMENTARY Paul Haggis Scott Rodger / Hwy61 THIRD PERSON Paul Haggis Guy Tannahill, Michael Nozik Official Selection - Tribeca Film Festival Corsan / Sony Pictures Classics Official Selection – Toronto Film Festival GANDHI OF THE MONTH Kranti Kanade Sanjay Singh THE NEXT THREE DAYS Paul Haggis Michael Nozik, Olivier Delbosc Marc Missonnier / Lionsgate IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH Paul Haggis Erik Feig, Patrick Wachsberger, Larry Becsey Warner Independent Pictures THE HOUSE OF USHER Hayley Cloake Boyd Hancock, Alyssa Weisberg Abernathy Productions STUDIO CITY Short Film Tom Verica Dana Rae ERROR IN JUDGMENT Asst. Editor Scott P. Levy Paul Colichman, Mark R. Harris BELLYFRUIT Asst. Editor Kerri Green Robert Bauer / Independent Women Artists TELEVISION COUNTERPART Season 1 Various Directors Tammy Ann Casper / MRC / Starz ANIMAL KINGDOM Season 1 Various Directors Terri Murphy, Lou Wells / Warner Bros. / TNT DAREDEVIL Season 2 Various Directors Doug Petrie, Marco Ramirez ABC / Marvel / Netflix SHOW ME A HERO Mini-series Paul Haggis Nina Noble, David Simon / HBO BATTLE CREEK Series Various Directors Cindy Kerber, David Shore, Richard Heus Vince Gilligan / Sony Pictures TV / CBS POWER Series Various Directors David Knoller, Mark Canton / CBS / Starz SALEM Pilot Richard Shepard Vahan Moosekian / WGN / Fox DECEPTION Pilot Peter Horton Jim Chory, Gail Berman, Lloyd Braun Gene Stein, Liz Heldens / NBC BOSS Series Mario Van Peebles Gus Van Sant, Farhad Safinia & Various Directors Lionsgate TV WE ARE THE WORLD: 25 FOR HAITI Paul Haggis Quincy Jones / AEG Live CRASH Series Bobby Moresco, Bobby Moresco, Ira Behr, Glen Mazzara Stefan Schwartz John Moranville / Lionsgate TV & Various Directors LOST 1 Episode Stephen Williams J.J. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Libby Found Guilty on Four out of Five Counts, Hopes for Presidential Pardon

Today: Partly Cloudy THE TUFTS High 27 Low 16 Tufts’ Student Tomorrow: Newspaper Flurries Since 1980 High 28 Low 6 VOLUME LIII, NUMBER 28 DAILY WEDNESDAY, MARCH 7, 2007 Libby found guilty on four out of fi ve New WebCenter feature lets counts, hopes for presidential pardon students export calendars BY BENNETT KUHN sophomore Neil DiBiase Daily Editorial Board agreed that the new service will help students. “In terms Students can now export of time saving, it’s a huge their class schedules and the impact to be able to hit one university’s academic calen- button and have your entire dar from Tufts’ WebCenter schedule downloaded,” he to popular software like said. Microsoft Outlook, iCal, Uploading dates from Palm Desktop and Google WebCenter adds to previ- Calendar. ously existing setups without The new service, called requiring students to scrap “My Course Schedule dates already on their calen- Download,” was announced dars. yesterday and lets students Furthermore, students can export information on the opt to upload either their dates, times and locations of personal course schedules or their classes directly to their just the academic calendar, electronic calendars, PDAs so those who have manually or smartphones. entered their classes before It can also transfer uni- the new WebCenter feature versity-wide drop dates, reg- became operational can add istration periods, vacations the university’s important and other important dates dates without their course from the Tufts academic cal- schedules. endar. Tutorials with screenshots Tufts Community Union and instructions also appear (TCU) Senator Woon Young on WebCenter to help stu- MCT Jeong, a sophomore who was dents integrate the files they I. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

Tchando Biography

Tchando Biography The new album 2018: << BA >> Salvador Embalo ‘Tchando’ comes from a small country on the west coast of Africa, named Guinea- Bissau. He was born in Bafatá (east) on March 22nd. 1957. Belonging to the Fulani tribe, surrounded by the Mandinka traditions, Tchando expresses the fusion of these two great African cultures. As a child, Tchando learned to play several traditional Fulani instruments, such as the don-don or tama (a drum), molla and hóddo (lutes of 3, 7 or 9 strings respectively). He settled in Bissau in 1965, where he lived in the Mandinka and Biafada dominated district (2 Guinean-Bissau ethnic groups), having quickly learned to play percussion instruments such as “Cutil N'Dium” and “Cutil Ba”. Later on, he learned to play the six-string guitar that eventually became his favourite instrument. Tchando's interests are not limited to music alone. He was always a great supporter of justice. Always aware of the constant violations of human rights in his country, he decided to confront his government and the single ruling party. This positioning against social injustice and the then repressive politics was taken as a counter-revolutionary act. As a consequence, Tchando was imprisoned during two long and gloomy years, 1977-1979, accused of treason to the homeland. It required the intervention of the Amnesty International in order for the Bissau-Guinean authorities finally try his case in a High Military Court, along with other comrades in the same case, twenty months after the date of their arrest. From 1982 to 1988 Tchando worked as a session musician and arranger in both Portugal and France and participated in the building up of several bands & artists as ‘Issabary’ and ‘Kabá Mané’ (he produced 2 albums for this artist - Chefo Mae-Mae and Kunga). -

The Irish-Canadian; Image and Self-Image, 1847-1870

THE IRISH-CANADIAN; IMAGE AND SELF-IMAGE, 1847-1870 by DANIEL CONNER B.A. (Hon.), Oxon., 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA AUGUST, 1976 (c), Daniel Christopher Conner, 1976 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be al1 owed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date October 6. 1976. ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the Irish-Catholic popula• tion of Canada was perceived and described by the newspapers of mid- Victorian Toronto and Montreal. A study of the leading political and religious journals at mid-century demonstrates the prolonged existence in Canada of hostile feelings towards the immigrant community, based both on Protestant aversion to Catholicism and on stereotypes of Irish character in general. The thesis argues that these antagonisms and un• favourable images were identified by the Irish community as contributing to its lack of economic, social and political progress. In defence against the hostility which they detected at all levels of society, and which was especially apparent in the vocabulary of disparagement and abuse with which Irish affairs were reported in Canadian newspapers, Irish-Catholics maintained a distinct and self-conscious sense of national community.