Carrying a Torch for Dust in Binary Star Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathématiques Et Espace

Atelier disciplinaire AD 5 Mathématiques et Espace Anne-Cécile DHERS, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Peggy THILLET, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Yann BARSAMIAN, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Olivier BONNETON, Sciences - U (mathématiques) Cahier d'activités Activité 1 : L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL Activité 2 : DENOMBREMENT D'ETOILES DANS LE CIEL ET L'UNIVERS Activité 3 : D'HIPPARCOS A BENFORD Activité 4 : OBSERVATION STATISTIQUE DES CRATERES LUNAIRES Activité 5 : DIAMETRE DES CRATERES D'IMPACT Activité 6 : LOI DE TITIUS-BODE Activité 7 : MODELISER UNE CONSTELLATION EN 3D Crédits photo : NASA / CNES L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL (3 ème / 2 nde ) __________________________________________________ OBJECTIF : Détermination de la ligne d'horizon à une altitude donnée. COMPETENCES : ● Utilisation du théorème de Pythagore ● Utilisation de Google Earth pour évaluer des distances à vol d'oiseau ● Recherche personnelle de données REALISATION : Il s'agit ici de mettre en application le théorème de Pythagore mais avec une vision terrestre dans un premier temps suite à un questionnement de l'élève puis dans un second temps de réutiliser la même démarche dans le cadre spatial de la visibilité d'un satellite. Fiche élève ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Victor Hugo a écrit dans Les Châtiments : "Les horizons aux horizons succèdent […] : on avance toujours, on n’arrive jamais ". Face à la mer, vous voyez l'horizon à perte de vue. Mais "est-ce loin, l'horizon ?". D'après toi, jusqu'à quelle distance peux-tu voir si le temps est clair ? Réponse 1 : " Sans instrument, je peux voir jusqu'à .................. km " Réponse 2 : " Avec une paire de jumelles, je peux voir jusqu'à ............... km " 2. Nous allons maintenant calculer à l'aide du théorème de Pythagore la ligne d'horizon pour une hauteur H donnée. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

GTO Keypad Manual, V5.001

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v5.xxx Please read the manual even if you are familiar with previous keypad versions Flash RAM Updates Keypad Java updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com/software-updates/ November 11, 2020 ASTRO-PHYSICS KEYPAD MANUAL FOR MACH2GTO Version 5.xxx November 11, 2020 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 4 REQUIREMENTS 5 What Mount Control Box Do I Need? 5 Can I Upgrade My Present Keypad? 5 GTO KEYPAD 6 Layout and Buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent Display 6 N-S-E-W Directional Buttons 6 STOP Button 6 <PREV and NEXT> Buttons 7 Number Buttons 7 GOTO Button 7 ± Button 7 MENU / ESC Button 7 RECAL and NEXT> Buttons Pressed Simultaneously 7 ENT Button 7 Retractable Hanger 7 Keypad Protector 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad Battery for 512K Memory Boards 8 Cleaning Red Keypad Display 8 Temperature Ratings 8 Environmental Recommendation 8 GETTING STARTED – DO THIS AT HOME, IF POSSIBLE 9 Set Up your Mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather Basic Information 9 Enter Your Location, Time and Date 9 Set Up Your Mount in the Field 10 Polar Alignment 10 Mach2GTO Daytime Alignment Routine 10 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR NEW SETUPS OR SETUP IN NEW LOCATION 11 Assemble Your Mount 11 Startup Sequence 11 Location 11 Select Existing Location 11 Set Up New Location 11 Date and Time 12 Additional Information 12 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR MOUNTS USED AT THE SAME LOCATION WITHOUT A COMPUTER 13 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR COMPUTER CONTROLLED MOUNTS 14 1 OBJECTS MENU – HAVE SOME FUN! -

Chemodynamical History of the Galactic Bulge Arxiv:1805.01142V1

Chemodynamical history of the Galactic Bulge Beatriz Barbuy1, Cristina Chiappini2, Ortwin Gerhard3 1Department of Astronomy, Universidade de S~aoPaulo, S~aoPaulo 05508-090, Brazil; e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2Leibniz-Institut f¨urAstrophysik Potsdam (AIP), An der Sternwarte 16, 14482, Potsdam, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] 3Max-Planck-Institut f¨urextraterrestrische Physik P.O. Box 1312. D-85741 Garching, Germany; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2018. Keywords 56:1{55 Copyright c 2018 by Annual Reviews. bulge, bar, stellar populations, chemical composition, dynamical All rights reserved evolution, chemical evolution, chemodynamical evolution Abstract The Galactic Bulge can uniquely be studied from large samples of in- dividual stars, and is therefore of prime importance for understanding the stellar population structure of bulges in general. Here the observa- tional evidence on the kinematics, chemical composition, and ages of Bulge stellar populations based on photometric and spectroscopic data is reviewed. The bulk of Bulge stars are old and span a metallicity range −1.5∼<[Fe/H]∼<+0.5. Stellar populations and chemical properties suggest a star formation timescale below ∼2 Gyr. The overall Bulge is barred and follows cylindrical rotation, and the more metal-rich stars trace a Box/Peanut (B/P) structure. Dynamical models demonstrate the different spatial and orbital distributions of metal-rich and metal- arXiv:1805.01142v1 [astro-ph.GA] 3 May 2018 poor stars. We discuss current Bulge formation scenarios based on dy- namical, chemical, chemodynamical and cosmological models. Despite impressive progress we do not yet have a successful fully self-consistent chemodynamical Bulge model in the cosmological framework, and we will also need more extensive chrono-chemical-kinematic 3D map of stars to better constrain such models. -

Cycle 12 Abstract Catalog

Cycle 12 Abstract Catalog Generated April 04, 2003 ================================================================================ Proposal Category: GO Scientific Category: ISM AND CIRCUMSTELLAR MATTER ID: 9718 Title: SMC Extinction Curve Towards a Quiescent Molecular Cloud PI: Francois Boulanger PI Institution: Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale The lack of 2175 A bump in the SMC extinction curve is interpreted as an absence of small carbon grains. ISO Mid-IR observations support this interpretation by showing that PAH features are absent in the spectra of SMC and LMC massive star forming regions. However, the only ISO observation of an SMC quiescent molecular cloud shows all PAH features, indicating a PAH abundance relative to large dust grains similar to that of Milky Way clouds. We identified a reddened B2III star associated with this cloud. We propose to observe it with STIS. This observation will provide the first measure of the extinction properties of SMC dust away from star forming regions. It will allow us to disentangle the effects of metallicity and massive stars on the SMC extinction curve and dust composition and to assess the relevance of the SMC bump-free extinction curve to low metallicity and/or starburst galaxies in general. ================================================================================ Proposal Category: GO Scientific Category: STELLAR POPULATIONS ID: 9719 Title: Search For Metallicity Spreads in M31 Globular Clusters PI: Terry Bridges PI Institution: Anglo-Australian Observatory Our recent deep HST photometry of the M31 halo globular cluster (GC) Mayall~II, also called G1, has revealed a red-giant branch with a clear spread that we attribute to an intrinsic metallicity dispersion of at least 0.4 dex in [Fe/H]. -

Jun 2017 Newsletter

Volume22, Issue 10 NWASNEWS June 2017 Newsletter for the Wiltshire, Swindon, Beckington AGM and ISS slides past the Moon! Astronomical Societies and Salisbury Plain Observing Group Firstly some very sad news to pass on. Paul Barrett, a long serving member who southern Wiltshire. Wiltshire Society Page 2 used to come to all meetings and many The time will be 10:30:22 seconds at Ave- Swindon Stargazers 3 observing sessions, lost his long, and a bury, it will miss Devizes, Calne, Swindon, fear painful battle with cancer just over a Salisbury and Marlborough (see map on Beckington and Astronomy 4 week ago. page 2. course at York His funeral will be at the Semington Crem- To catch this we need to leave at 9:45, no Space Place Fizzing Seas of 5 atorium on 16th June. Donations to Doro- later. I am asking that the AGM be moved Titan thy House. to September, as we have done in the past. It may be necessary, as I am also Space news. Space X success 6-19 Very sorry to here this and condolences to 5th June, Star v Black Hole, his family. aware of three committee members who will be unable to make the meeting. We Jupiter images from Jove, Lu- nar Orbiter camera hit by mete- can run through the accounts, but need orite, Hard Rock rain hits the Tonight’s meeting should be our AGM, and detailed discussions on officers, web site, Moon, New Zealand rocket we have a speaker Mark Radice, a local a and constitution so the new chair can run launch, Low(ish) mass star occasional speaker to the society, this time with a clean sheet and positive bank bal- goes to black hole not nebula, he will be telling us about his experiences ance. -

GTO KEYPAD Version V4.19.3

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v4.19.3 Flash RAM Updates Keypad flash RAM updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com periodically for further information. July 29, 2016 Contents About this mAnuAl 5 GTO KeypAd ContRolleR 6 layout and buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent display 6 n-s-e-W directional buttons 6 RA/deC ReV button: 6 STOP button 7 number buttons 7 <pReV and neXt> buttons 7 Goto button 7 ± button 7 menu button 7 FoC button 7 Retractable hanger 7 Keypad protector 7 installation: 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad battery for 256K memory boards 8 Keypad battery for 512K memory boards 8 Cleaning Keypad display 8 temperature Ratings 8 GettinG stARted – do this At home, iF possible 9 setup your mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather basic information 9 enter your location, date and time 9 practice using your Keypad 11 youR FiRst obseRVinG session & FoR poRtAble mounts 12 normal startup sequence for mounts that are in the field 12 Assemble your mount 12 startup sequence 12 star sync 12 Resume last position 13 new setup → new setup start From park position (press 1, 2, 3, or 4) 13 helpful hints 13 AUTO-ConneCt seQuenCe – FoR peRmAnent, polAR-AliGned mounts 14 important points 14 eXteRnAl stARtup seQuenCe – FoR ComputeR ContRolled mounts 15 important points 15 polAR AliGnment – WhiCh method to Choose? 16 n polar Calibrate - Calibrating with polaris 16 two-star Calibration 17 polar Aligning in the daytime – northern hemisphere 20 polar Aligning in the daytime – southern -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

December 1997

No. 90 – December 1997 T E L E S C O P E S A N D I N S T R U M E N T A T I O N A Deep Field with the Upgraded NTT S. D’ODORICO, ESO This colour deep image has been prepared from 4 deep images through the filters B, V, r and i obtained with the SUSI CCD imager at the ESO NTT. The image covers a 2.2 × 2.2 arcmin “emp- ty” field centred about 2 arcminutes south of the z = 4.7 QSO BR 1202- 0725. The four images result from the co-addition of dithered short integra- tions for a total of 52,800, 23,400, 23,400 and 16,200 seconds in the four bands, and the co-added images have average FWHMs of 0.84, 0.80, 0.80 and 0.68 arcsec respectively. The data were obtained for a scientif- ic programme approved for the ESO Period 58 and aimed at the study of the photometric redshift distribution of the faint galaxies and of gravitational lens- ing effects in the field. The P.I. of the proposal is Sandro D’Odorico and the Co-P.I. are J. Bergeron, H.M. Adorf, S. Charlot, D. Clements, S. Cristiani, L. da Costa, E. Egami, A. Fontana, B. Fort, L. Gautret, E. Giallongo, R. Gilmozzi, R.N. Hook, B. Leibundgut, Y. Mellier, P. Petitjean, A. Renzini, S. Savaglio, P. Shaver, S. Seitz and L. Yan. The pro- gramme was executed in service mode by the NTT team in February through April 1997 in photometric nights with seeing better than 1 arcsec. -

Lists and Charts of Autostar Named Stars

APPENDIX A Lists and Charts of Autostar Named Stars Table A.I provides a list of named stars that are stored in the Autostar database. Following the list, there are constellation charts which show where the stars are located. The names are in alphabetical orderalong with their Latin designation (see Appendix B for complete list ofconstellations). Names in brackets 0 in the table denote a different spelling to one that is known in the list. The star's co-ordinates are set to the same as accuracy as the Autostar co-ordinates i.e. the RA or Dec 'sec' values are omitted. Autostar option: Select Item: Object --+ Star --+ Named 215 216 Appendix A Table A.1. Autostar Named Star List RA Dec Named Star Fig. Ref. latin Designation Hr Min Deg Min Mag Acamar A5 Theta Eridanus 2 58 .2 - 40 18 3.2 Achernar A5 Alpha Eridanus 1 37.6 - 57 14 0.4 Acrux A4 Alpha Crucis 12 26.5 - 63 05 1.3 Adara A2 EpsilonCanis Majoris 6 58.6 - 28 58 1.5 Albireo A4 BetaCygni 19 30.6 ++27 57 3.0 Alcor Al0 80 Ursae Majoris 13 25.2 + 54 59 4.0 Alcyone A9 EtaTauri 3 47.4 + 24 06 2.8 Aldebaran A9 Alpha Tauri 4 35.8 + 16 30 0.8 Alderamin A3 Alpha Cephei 21 18.5 + 62 35 2.4 Algenib A7 Gamma Pegasi 0 13.2 + 15 11 2.8 Algieba (Algeiba) A6 Gamma leonis 10 19.9 + 19 50 2.6 Algol A8 Beta Persei 3 8.1 + 40 57 2.1 Alhena A5 Gamma Geminorum 6 37.6 + 16 23 1.9 Alioth Al0 EpsilonUrsae Majoris 12 54.0 + 55 57 1.7 Alkaid Al0 Eta Ursae Majoris 13 47.5 + 49 18 1.8 Almaak (Almach) Al Gamma Andromedae 2 3.8 + 42 19 2.2 Alnair A6 Alpha Gruis 22 8.2 - 46 57 1.7 Alnath (Elnath) A9 BetaTauri 5 26.2 -

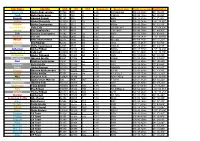

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral Class Right Ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral class Right ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B8IVpMnHg 00h 08,388m 29° 05,433' Caph Beta Cassiopeiae 21133 432 2 2,27 F2III-IV 00h 09,178m 59° 08,983' Algenib Gamma Pegasi 91781 886 7 2,83 B2IV 00h 13,237m 15° 11,017' Ankaa Alpha Phoenicis 215093 2261 12 2,39 K0III 00h 26,283m - 42° 18,367' Schedar Alpha Cassiopeiae 21609 3712 21 2,23 K0IIIa 00h 40,508m 56° 32,233' Deneb Kaitos Beta Ceti 147420 4128 22 2,04 G9.5IIICH-1 00h 43,590m - 17° 59,200' Achird Eta Cassiopeiae 21732 4614 3,44 F9V+dM0 00h 49,100m 57° 48,950' Tsih Gamma Cassiopeiae 11482 5394 32 2,47 B0IVe 00h 56,708m 60° 43,000' Haratan Eta ceti 147632 6805 40 3,45 K1 01h 08,583m - 10° 10,933' Mirach Beta Andromedae 54471 6860 42 2,06 M0+IIIa 01h 09,732m 35° 37,233' Alpherg Eta Piscium 92484 9270 50 3,62 G8III 01h 13,483m 15° 20,750' Rukbah Delta Cassiopeiae 22268 8538 48 2,66 A5III-IV 01h 25,817m 60° 14,117' Achernar Alpha Eridani 232481 10144 54 0,46 B3Vpe 01h 37,715m - 57° 14,200' Baten Kaitos Zeta Ceti 148059 11353 62 3,74 K0IIIBa0.1 01h 51,460m - 10° 20,100' Mothallah Alpha Trianguli 74996 11443 64 3,41 F6IV 01h 53,082m 29° 34,733' Mesarthim Gamma Arietis 92681 11502 3,88 A1pSi 01h 53,530m 19° 17,617' Navi Epsilon Cassiopeiae 12031 11415 63 3,38 B3III 01h 54,395m 63° 40,200' Sheratan Beta Arietis 75012 11636 66 2,64 A5V 01h 54,640m 20° 48,483' Risha Alpha Piscium 110291 12447 3,79 A0pSiSr 02h 02,047m 02° 45,817' Almach Gamma Andromedae 37734 12533 73 2,26 K3-IIb 02h 03,900m 42° 19,783' Hamal Alpha -

A Data Viewer for R

Paul Murrell A Data Viewer for R A Data Viewer for R Paul Murrell The University of Auckland July 30 2009 Paul Murrell A Data Viewer for R Overview Motivation: STATS 220 Problem statement: Students do not understand what they cannot see. What doesn’t work: View() A solution: The rdataviewer package and the tcltkViewer() function. What else?: Novel navigation interface, zooming, extensible for other data sources. Paul Murrell A Data Viewer for R STATS 220 Data Technologies HTML (and CSS), XML (and DTDs), SQL (and databases), and R (and regular expressions) Online text book that nobody reads Computer lab each week (worth 0.5%) + three Assignments 5 labs + one assignment on R Emphasis on creating and modifying data structures Attempt to use real data Paul Murrell A Data Viewer for R Example Lab Question Read the file lab10.txt into R as a character vector. You should end up with a symbol habitats that prints like this (this shows just the first 10 values; there are 192 values in total): > head(habitats, 10) [1] "upwd1201" "upwd0502" "upwd0702" [4] "upwd1002" "upwd1102" "upwd0203" [7] "upwd0503" "upwd0803" "upwd0104" [10] "upwd0704" Paul Murrell A Data Viewer for R The file lab10.txt upwd1201 upwd0502 upwd0702 upwd1002 upwd1102 upwd0203 upwd0503 upwd0803 upwd0104 upwd0704 upwd0804 upwd1204 upwd0805 upwd1005 upwd0106 dnwd1201 dnwd0502 dnwd0702 dnwd1002 dnwd1102 dnwd1202 dnwd0103 dnwd0203 dnwd0303 dnwd0403 dnwd0503 dnwd0803 dnwd0104 dnwd0704 dnwd0804 dnwd1204 dnwd0805 dnwd1005 dnwd0106 uppl0502 uppl0702 uppl1002 uppl1102 uppl0203 uppl0503