Performance of Four Seed-Caching Corvid Species in the Radial-Arm Maze Analog" (1994)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications of Climate Change for Food-Caching Species

Demographic and Environmental Drivers of Canada Jay Population Dynamics in Algonquin Provincial Park, ON by Alex Odenbach Sutton A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Alex O. Sutton, April 2020 ABSTRACT Demographic and Environmental Drivers of Canada Jay Population Dynamics in Algonquin Provincial Park, ON Alex Sutton Advisor: University of Guelph, 2020 Ryan Norris Knowledge of the demographic and environmental drivers of population growth throughout the annual cycle is essential to understand ongoing population change and forecast future population trends. Resident species have developed a suite of behavioural and physiological adaptations that allow them to persist in seasonal environments. Food-caching is one widespread behavioural mechanism that involves the deferred consumption of a food item and special handling to conserve it for future use. However, once a food item is stored, it can be exposed to environmental conditions that can either degrade or preserve its quality. In this thesis, I combine a novel framework that identifies relevant environmental conditions that could cause cached food to degrade over time with detailed long-term demographic data collected for a food-caching passerine, the Canada jay (Perisoreus canadensis), in Algonquin Provincial Park, ON. In my first chapter, I develop a framework proposing that the degree of a caching species’ susceptibility to climate change depends primarily on the duration of storage and the perishability of food stored. I then summarize information from the field of food science to identify relevant climatic variables that could cause cached food to degrade. -

Camp Chiricahua July 16–28, 2019

CAMP CHIRICAHUA JULY 16–28, 2019 An adult Spotted Owl watched us as we admired it and its family in the Chiricahuas © Brian Gibbons LEADERS: BRIAN GIBBONS, WILLY HUTCHESON, & ZENA CASTEEL LIST COMPILED BY: BRIAN GIBBONS VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM By Brian Gibbons Gathering in the Sonoran Desert under the baking sun didn’t deter the campers from finding a few life birds in the parking lot at the Tucson Airport. Vermilion Flycatcher, Verdin, and a stunning male Broad-billed Hummingbird were some of the first birds tallied on Camp Chiricahua 2019 Session 2. This was more than thirty years after Willy and I had similar experiences at Camp Chiricahua as teenagers—our enthusiasm for birds and the natural world still vigorous and growing all these years later, as I hope yours will. The summer monsoon, which brings revitalizing rains to the deserts, mountains, and canyons of southeast Arizona, was tardy this year, but we would see it come to life later in our trip. Rufous-winged Sparrow at Arizona Sonora Desert Museum © Brian Gibbons On our first evening we were lucky that a shower passed and cooled down the city from a baking 104 to a tolerable 90 degrees for our outing to Sweetwater Wetlands, a reclaimed wastewater treatment area where birds abound. We found twittering Tropical Kingbirds and a few Abert’s Towhees in the bushes surrounding the ponds. Mexican Duck, Common Gallinule, and American Coot were some of the birds that we could find on the duckweed-choked ponds. -

The Perplexing Pinyon Jay

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 1998 The Ecology and Evolution of Spatial Memory in Corvids of the Southwestern USA: The Perplexing Pinyon Jay Russell P. Balda Northern Arizona University,, [email protected] Alan Kamil University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Balda, Russell P. and Kamil, Alan, "The Ecology and Evolution of Spatial Memory in Corvids of the Southwestern USA: The Perplexing Pinyon Jay" (1998). Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published (as Chapter 2) in Animal Cognition in Nature: The Convergence of Psychology and Biology in Laboratory and Field, edited by Russell P. Balda, Irene M. Pepperberg, and Alan C. Kamil, San Diego (Academic Press, 1998), pp. 29–64. Copyright © 1998 by Academic Press. Used by permission. The Ecology and Evolution of Spatial Memory in Corvids of the Southwestern USA: The Perplexing Pinyon Jay Russell P. Balda 1 and Alan C. Kamil 2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Northern -

A Fossil Scrub-Jay Supports a Recent Systematic Decision

THE CONDOR A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 98 Number 4 November 1996 .L The Condor 98~575-680 * +A. 0 The Cooper Omithological Society 1996 g ’ b.1 ;,. ’ ’ “I\), / *rs‘ A FOSSIL SCRUB-JAY SUPPORTS A”kECENT ’ js.< SYSTEMATIC DECISION’ . :. ” , ., f .. STEVEN D. EMSLIE : +, “, ., ! ’ Department of Sciences,Western State College,Gunnison, CO 81231, ._ e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nine fossil premaxillae and mandibles of the Florida Scrub-Jay(Aphelocoma coerulescens)are reported from a late Pliocene sinkhole deposit at Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Vertebrate biochronologyplaces the site within the latestPliocene (2.0 to 1.6 million yearsago, Ma) and more specificallyat 2.0 l-l .87 Ma. The fossilsare similar in morphology to living Florida Scrub-Jaysin showing a relatively shorter and broader bill compared to western species,a presumed derived characterfor the Florida species.The recent elevation of the Florida Scrub-Jayto speciesrank is supported by these fossils by documenting the antiquity of the speciesand its distinct bill morphology in Florida. Key words: Florida; Scrub-Jay;fossil; late Pliocene. INTRODUCTION represent the earliest fossil occurrenceof the ge- nus Aphelocomaand provide additional support Recently, the Florida Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma for the recognition ofA. coerulescensas a distinct, coerulescens) has been elevated to speciesrank endemic specieswith a long fossil history in Flor- with the Island Scrub-Jay(A. insularis) from Santa ida. This record also supports the hypothesis of Cruz Island, California, and the Western Scrub- Pitelka (195 1) that living speciesof Aphefocoma Jay (A. californica) in the western U. S. and Mex- arose in the Pliocene. ico (AOU 1995). -

Greenlee County

Birding Arizona BIRDING SOUTHERN GREENLEE COUNTY By Tommy Debardeleben INTRODUCTION Greenlee County is Arizona’s second smallest county, the least populated, and by far the most underbirded. The latter aspect fired Caleb Strand, Joshua Smith, and I to focus an entire weekend gathering data about the Flagsta birds of this county, as well as building our county lists. Starting Thursday Greenlee night, 16 February 2017, and ending Saturday night, 18 February 2017, County we covered a wide range of locations in the southern part of the county. Although small, Greenlee County has many habitats, with elevations Phoenix ranging from just over 3,000 ft in Chihuahuan desert scrub to over 9,000 ft in spruce-fir forest in the Hannagan Meadow area of the White Mountains. Tucson On this trip we didn’t go north to the White Mountains. DUNCAN We left the Phoenix area around 6 PM on Thursday night and arrived in Duncan after 10 PM. Duncan is situated at an elevation of 3655 ft and has a population of about 750 people, according to a 2013 census. We started owling immediately when we arrived. It wasn’t long before we had our first bird, a Great Horned Owl in town. We stayed at the Chaparral Hotel, which is a small hotel with good rates that is close to any Duncan or Franklin birding location. After getting situated at our motel, we drove a short distance to the Duncan Birding Trail, perhaps the county seat of birding hotspots in Greenlee County. We owled there for about an hour and were rewarded with a second Great Horned Owl, a pair of cooperative and up-close Western Screech-Owls, and a stunning Barn Owl calling and flying overhead several times. -

Connecting Mountain Islands and Desert Seas

Abundance of Birds in the Oak Savannas of the Southwestern United States Wendy D. Jones, Carlton M. Jones, and Peter F. Ffolliott School of Natural Resources, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Gerald J. Gottfried Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Phoenix, AZ Abstract—Oak ecosystems of the Southwestern United States are important habitats for a variety of wildlife species. Information is available on the abundance and habitat preferences of some species inhabiting the more densely structured oak woodlands, but little information is available on these topics for the comparatively open oak savannas. Studies are underway to alleviate this situation by determining the abundance of wildlife species commonly found in the oak savannas, identifying the habitat preferences of these species, and assessing the impacts of prescribed burn- ing on the wildlife species. Initial estimates of the abundance of birds in oak savannas obtained in the first year of a comprehensive investigation on the abundance and habitat preferences of a more complete representation of avifauna, mammals, and herpetofauna inhabiting oak savannas are presented in this paper. evaluate the impacts of prescribed burning on ecological and Introduction hydrologic characteristics of these watersheds (Gottfried and Abundance and habitat preferences of birds and some of the others 2000) are (collectively) the study area. The areal ag- other wildlife found in the densely structured oak woodlands gregation of these watersheds, called the Cascabel watersheds, of the Southwestern United States are known for some of the is about 450 acres. Baseline geological and physiological representative species, but little information on these topics characteristics of the Cascabel watersheds have been de- is available for the more open oak savannas of the region. -

Chiricahua Mountains Annotated Bird Checklist Scheduled for Publication Early This Year by Kathy L

Chiricahua Mountains Annotated Bird Checklist Scheduled for Publication Early This Year By Kathy L. Hiett, R. Roy Johnson, and Michael R. Kunzmann Southeastern Arizona may be the premiere inland During the avian and floristic studies conducted by Publication Components and bird watching locality for the United States, and is CPSU/UA scientists, the mountain island diversity the Information Management considered by many ornithologists and birders to be ory was examined as well as the biological diversity of Prominent ornithologists and others who have stud excelled by few other places in the world, but only in the range. The high avian species richness, and floral ied the Chiricahua Mountains were invited to submit recent years has the popularity of the area become and vegetative diversity is largely due to the ecotonal essays that provide the reader with a broader perspec apparent. Portal, a small community on the eastern nature of the region. Lowland diversity is derived from tive of the cultural and natural history of the area and fringe of the range caters to birding groups and dis the convergence of species from the Chihuahuan Des birds found here. Dr. Jerram Brown, SUN, the top penses information on local attractions. The U.S. For ert to the southeast and plains grasslands to the north authority on Gray-breasted Jays (formerly Mexican est Service provides local information, maps and a east, with those from the Sonoran Desert to the west. Jay), has authored an essay on the value of long-term checklist (1989) of birds in the Chiricahuas and oper Species richness for montane forest and woodland observations and the stability of the jay population ates recreational facilities throughout the range that diversity derives from Rocky Mountain vegetation to during his 20 year study in the Chiricahuas. -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a Field Checklist

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a field checklist Black-throated Sparrow by Kelly B. Bryan Birds of the Trans-Pecos: a field checklist the chihuahuan desert Traditionally thought of as a treeless desert wasteland, a land of nothing more than cacti, tumbleweeds, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes – West Texas is far from it. The Chihuahuan Desert region of the state, better known as the Trans-Pecos of Texas (Fig. 1), is arguably the most diverse region in Texas. A variety of habitats ranging from, but not limited to, sanddunes, desert-scrub, arid canyons, oak-juniper woodlands, lush riparian woodlands, plateau grasslands, cienegas (desert springs), pinyon-juniper woodlands, pine-oak woodlands and montane evergreen forests contribute to a diverse and complex avifauna. As much as any other factor, elevation influences and dictates habitat and thus, bird occurrence. Elevations range from the highest point in Texas at 8,749 ft. (Guadalupe Peak) to under 1,000 ft. (below Del Rio). Amazingly, 106 peaks in the region are over 7,000 ft. in elevation; 20 are over 8,000 ft. high. These montane islands contain some of the most unique components of Texas’ avifauna. As a rule, human population in the region is relatively low and habitat quality remains good to excellent; habitat types that have been altered the most in modern times include riparian corridors and cienegas. Figure 1: Coverage area is indicated by the shaded area. This checklist covers all of the area west of the Pecos River and a corridor to the east of the Pecos River that contains areas of Chihuahuan Desert habitat types. -

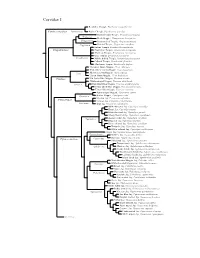

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

The White-Throated Magpie-Jay

THE WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE-JAY BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ORE than 15 years have passed since I was last in the haunts of the M White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa) . During the years when I travelled more widely through Central America I saw much of this bird, and learned enough of its habits to convince me that it would well repay a thorough study. Since it now appears unlikely that I shall make this study myself, I wish to put on record such information as I gleaned, in the hope that these fragmentary notes will stimulate some other bird- watcher to give this jay the attention it deserves. A big, long-tailed bird about 20 inches in length, with blue and white plumage and a high, loosely waving crest of recurved black feathers, the White-throated Magpie-Jay is a handsome species unlikely to be confused with any other member of the family. Its upper parts, including the wings and most of the tail, are blue or blue-gray with a tinge of lavender. The sides of the head and all the under plumage are white, and the outer feathers of the strongly graduated tail are white on the terminal half. A narrow black collar crosses the breast and extends half-way up each side of the neck, between the white and the blue. The stout bill and the legs and feet are black. The sexes are alike in appearance. The species extends from the Mexican states of Colima and Puebla to northwestern Costa Rica. A bird of the drier regions, it is found chiefly along the Pacific coast from Mexico southward as far as the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. -

Distribution Habitat and Social Organization of the Florida Scrub Jay

DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT, AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB JAY, WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATIVE BREEDING IN NEW WORLD JAYS BY JEFFREY A. COX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 To my wife, Cristy Ann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank, the following people who provided information on the distribution of Florida Scrub Jays or other forms of assistance: K, Alvarez, M. Allen, P. C. Anderson, T. H. Below, C. W. Biggs, B. B. Black, M. C. Bowman, R. J. Brady, D. R. Breininger, G. Bretz, D. Brigham, P. Brodkorb, J. Brooks, M. Brothers, R. Brown, M. R. Browning, S. Burr, B. S. Burton, P. Carrington, K. Cars tens, S. L. Cawley, Mrs. T. S. Christensen, E. S. Clark, J. L. Clutts, A. Conner, W. Courser, J. Cox, R. Crawford, H. Gruickshank, E, Cutlip, J. Cutlip, R. Delotelle, M. DeRonde, C. Dickard, W. and H. Dowling, T. Engstrom, S. B. Fickett, J. W. Fitzpatrick, K. Forrest, D. Freeman, D. D. Fulghura, K. L. Garrett, G. Geanangel, W. George, T. Gilbert, D. Goodwin, J. Greene, S. A. Grimes, W. Hale, F. Hames, J. Hanvey, F. W. Harden, J. W. Hardy, G. B. Hemingway, Jr., 0. Hewitt, B. Humphreys, A. D. Jacobberger, A. F. Johnson, J. B. Johnson, H. W. Kale II, L. Kiff, J. N. Layne, R. Lee, R. Loftin, F. E. Lohrer, J. Loughlin, the late C. R. Mason, J. McKinlay, J. R. Miller, R. R. Miller, B.