The Decade in Architecture: Strutting Structures Soaring in Triumph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “International” Skyscraper: Observations 2. Journal Paper

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The “International” Skyscraper: Observations Author: Georges Binder, Managing Director, Buildings & Data SA Subject: Urban Design Keywords: Density Mixed-Use Urban Design Verticality Publication Date: 2008 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2008 Issue I Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Georges Binder The “International” Skyscraper: Observations While using tall buildings data, the following paper aims to show trends and shifts relating to building use and new locations accommodating high-rise buildings. After decades of the American office building being dominate, in the last twelve years we have observed a gradual but major shift from office use to residential and mixed-use for Tall Buildings, and from North America to Asia. The turn of the millennium has also seen major changes in the use of buildings in cities having the longest experience with Tall Buildings. Chicago is witnessing a series of office buildings being transformed into residential or mixed-use buildings, a phenomenon also occurring on a large scale in New York. In midtown Manhattan of New York City we note the transformation of major hotels into residential projects. The transformation of landmark projects in midtown New York City is making an impact, but it is not at all comparable to the number of new projects being built in Asia. When conceiving new projects, we should perhaps bear in mind that, in due time, these will also experience major shifts in uses and we should plan for this in advance. -

CTBUH Technical Paper

CTBUH Technical Paper http://technicalpapers.ctbuh.org Subject: Other Paper Title: Talking Tall: The Global Impact of 9/11 Author(s): Klerks, J. Affiliation(s): CTBUH Publication Date: 2011 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal 2011 Issue III Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat/Author(s) CTBUH Journal International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat Tall buildings: design, construction and operation | 2011 Issue III Special Edition World Trade Center: Ten Years On Inside Case Study: One World Trade Center, New York News and Events 36 Challenging Attitudes on 14 “While, in an era of supertall buildings, big of new development. The new World Trade Bridging over the tracks was certainly an Center Transportation Hub alone will occupy engineering challenge. “We used state-of-the- numbers are the norm, the numbers at One 74,300 square meters (800,000 square feet) to art methods of analysis in order to design one Codes and Safety serve 250,000 pedestrians every day. Broad of the primary shear walls that extends all the World Trade are truly staggering. But the real concourses (see Figure 2) will connect Tower way up the tower and is being transferred at One to the hub’s PATH services, 12 subway its base to clear the PATH train lines that are 02 This Issue story of One World Trade Center is the lines, the new Fulton Street Transit Center, the crossing it,” explains Yoram Eilon, vice Kenneth Lewis Nicholas Holt World Financial Center and Winter Garden, a president at WSP Cantor Seinuk, the structural innovative solutions sought for the ferry terminal, underground parking, and retail engineers for the project. -

True to the City's Teeming Nature, a New Breed of Multi-Family High Rises

BY MEI ANNE FOO MAY 14, 2016 True to the city’s teeming nature, a new breed of multi-family high rises is fast cropping up around New York – changing the face of this famous urban jungle forever. New York will always be known as the land of many towers. From early iconic Art Deco splendours such as the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, to the newest symbol of resilience found in the One World Trade Center, there is no other city that can top the Big Apple’s supreme skyline. Except itself. Tall projects have been proposed and built in sizeable numbers over recent years. The unprecedented boom has been mostly marked by a rise in tall luxury residential constructions, where prior to the completion of One57 in 2014, there were less than a handful of super-tall skyscrapers in New York. Now, there are four being developed along the same street as One57 alone. Billionaire.com picks the city’s most outstanding multi-family high rises on the concrete horizon. 111 Murray Street This luxury residential tower developed by Fisher Brothers and Witkoff will soon soar some 800ft above Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood. Renderings of the condominium showcase a curved rectangular silhouette that looks almost round, slightly unfolding at the highest floors like a flared glass. The modern design is from Kohn Pedersen Fox. An A-team of visionaries has also been roped in for the project, including David Mann for it residence interiors; David Rockwell for amenities and public spaces and Edmund Hollander for landscape architecture. -

Technological Advances and Trends in Modern High-Rise Buildings

buildings Article Technological Advances and Trends in Modern High-Rise Buildings Jerzy Szolomicki 1,* and Hanna Golasz-Szolomicka 2 1 Faculty of Civil Engineering, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, 50-370 Wroclaw, Poland 2 Faculty of Architecture, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, 50-370 Wroclaw, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-505-995-008 Received: 29 July 2019; Accepted: 22 August 2019; Published: 26 August 2019 Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to provide structural and architectural technological solutions applied in the construction of high-rise buildings, and present the possibilities of technological evolution in this field. Tall buildings always have relied on technological innovations in engineering and scientific progress. New technological developments have been continuously taking place in the world. It is closely linked to the search for efficient construction materials that enable buildings to be constructed higher, faster and safer. This paper presents a survey of the main technological advancements on the example of selected tall buildings erected in the last decade, with an emphasis on geometrical form, the structural system, sophisticated damping systems, sustainability, etc. The famous architectural studios (e.g., for Skidmore, Owings and Merill, Nikhen Sekkei, RMJM, Atkins and WOHA) that specialize, among others, in the designing of skyscrapers have played a major role in the development of technological ideas and architectural forms for such extraordinary engineering structures. Among their completed projects, there are examples of high-rise buildings that set a precedent for future development. Keywords: high-rise buildings; development; geometrical forms; structural system; advanced materials; damping systems; sustainability 1. -

P21 Layout 1

EU investigates German current account surplus Page 22 Business Risk appetite subdued on US Fed uncertainty THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2013 Page 24 The Rolls-Royce Arab Spring economies hit by uncertainty Phantom SeriesII Page 23 Page 25 CHICAGO: In this file photo, the 110-storey, 1,450-foot Willis Tower rises above the Chicago skyline. According to the nonprofitCouncil on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, Willis Tower, formerly known as the Sears Tower, will be the tenth tallest completed building in the world, with a height measured at 1,451 feet, once New York’s 1 World Trade Center, with a height of 1,776 feet, is completed. — AP One World Trade Center named US tallest building 1,451-foot Willis Tower dethroned NEW YORK: They set out to build the tallest skyscraper in the near Central Park. Speaking at his office in New York, council chair- world - a giant that would rise a symbolic 1,776 feet from the ash- man Timothy Johnson, an architect at the global design firm NBBJ, es of ground zero. Those aspirations of global supremacy fell by said the decision by the 25-member height committee had more the wayside long ago, but New York won a consolation prize “tense moments” than usual, given the skyscraper’s importance as Tuesday when an international architectural panel said it would a patriotic symbol. recognize One World Trade Center - at 541 meters high - as the “I was here on 9/11. I saw the buildings come down,” he said. tallest skyscraper in the United States. Over the past few months, the council had hinted that it might be The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, considered a open to changing its standards for measuring ultra-tall buildings, world authority on supersized skyscrapers, announced its decision given a trend toward developers adding “vanity height” to towers at simultaneous news conferences in New York and Chicago, with huge, decorative spires. -

Breaking New Ground 2017 Annual Report

BREAKING NEW GROUND 2017 Annual Report Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2017. Our Mission Meet the critical transportation infrastructure needs of the bi-state region’s people, businesses, and visitors by providing the highest-quality and most efficient transportation and port commerce facilities and services to move people and goods within the region, provide access to the nation and the world, and promote the region’s economic development. Our mission is simple: to keep the region moving. 2 THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NY & NJ TABLE OF CONTENTS I ntroductory Section 2 Origins of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 3 Letter of Transmittal to the Governors 4 Board of Commissioners 5 Leadership of the Port Authority Our Core Business Imperatives 9 Investment 10 Safety and Security 11 Integrity 12 Diversity and Inclusion 13 Sustainability and Resiliency Major Milestones By Business Line 15 2017 at a Glance 16 Aviation 20 Tunnels, Bridges & Terminals 24 Port of New York and New Jersey 28 Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corporation (PATH) 30 World Trade Center Financial Section 32 Chief Financial Officer’s Letter of Transmittal to the Board of Commissioners 35 Index to Financial Section Corporate Information Section 126 Selected Statistical, Demographic, and Economic Data 127 Top 20 Salaried Staff as of December 31, 2017 The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Prepared by the Marketing and Comptroller’s departments of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 4 World Trade Center, 150 Greenwich Street, 23rd Floor, New York, NY 10007 www.panynj.gov BREAKING NEW GrounD 1 The Port District includes the cities of New York and Yonkers in New York State; the cities of Newark, Jersey City, Bayonne, Hoboken, and Elizabeth in the State of New Jersey; and more than 200 other municipalities, including all or part of 17 counties, in the two states. -

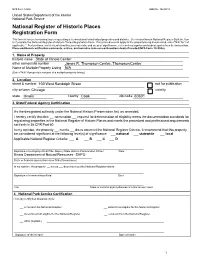

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

January 2016 the Future of NYC Real Estate

January 2016 http://therealdeal.com/issues_articles/the-future-of-nyc-real-estate-2/ The Future of NYC real estate Kinetic buildings and 2,000-foot skyscrapers are just around the corner By Kathryn Brenzel The Hudson Yards Culture Shed, a yet-to-be-built arts and performance space at 10 Hudson Yards, just might wind up being the Batmobile of buildings. Dormant, it’s a glassy fortress. Animated, it will be able to extend its wings so-to-speak by sliding out a retractable exterior as a canopy. The design is a window into the future of New York City construction — and the role technology will play. This isn’t to say that a fleet of moving buildings will invade New York anytime soon, but the projects of the future will be smarter, more adaptive and, of course, more awe-inspiring. “I think you’re going to start having more and more facades that are more kinetic, that react to the environment,” said Tom Scarangello, CEO of Thornton Tomasetti, a New York-based engineering firm that’s working on the Culture Shed. For example, Westfield’s Oculus, the World Trade Center’s new bird-like transit hub, features a retractable skylight whose function is more symbolic than practical: It opens only on Sept. 11. As a whole, developers are moving away from the shamelessly reflective glass boxes of the past, instead opting for transparent-yet-textured buildings as well as slender, soaring towers à la Billionaires’ Row. They are already beginning to experiment with different building materials, such as trading steel for wood in the city’s first “plyscraper,” which is being planned at 475 West 18th Street. -

Symbolism and the City: from Towers of Power to 'Ground Zero'

Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays (Vol: 15) Symbolism and the city: From towers of power to ‘Ground Zero’ Robert Patrick University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK Canada Amy MacDonald University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB Canada Abstract This paper explores the symbolism of New York City’s World Trade Center (WTC) before and after the devastating attack of September 11, 2001. The many metaphors captured in the built space of the WTC site are interrogated from ‘Ground Zero’ to the symbolic significance of the new ‘Freedom Tower’ now nearing completion (2014). In fulfilling the intended symbolism of American economic power, the WTC towers became pop-culture symbols of New York City, and the Unit- ed States. The WTC towers stood as twin icons of western economic dominance along with ‘Wall Street’ and ‘Dow Jones’ reflecting the American ethos of freedom and opportunity. However, the WTC also imbued negative, albeit unintended, symbolism such as the coldness of modernist architecture, social class disparities across urban America, and global domina- tion. Plans for redeveloping the WTC site predominantly highlight the intended positive symbolic connotations of the for- mer Twin Towers, including freedom and opportunity. This article points to the symbolic significance of urban built form and the potential negative consequences that are associated with iconic structures, including the new Freedom Tower. Keywords: symbolism, iconic architecture, New York City, World Trade Center Introduction tions leading to positive and negative actions of individuals and On September 11, 2001 a terrorist attack of horrific propor- groups. Indeed, there is a long fascination among geographers tions destroyed the New York World Trade Center and surround- and planners to the symbolic functions of ‘architectural gigan- ing structures. -

Repairs on the Verizon

GOTHAM GIGS FROM BOMBS TO BIKES Combat engineer puts the pieces back together CRAIN’S® NEW YORK BUSINESS PAGE 8 VOL. XXIX, NO. 2 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM JANUARY 14-20, 2013 PRICE: $3.00 Repairs on the CUOMO’S Verizon Telecom’s $1B worth of Sandy damage CASINO could offer silver lining for company FLIP BY MATTHEW FLAMM Nearly three months after Super- storm Sandy knocked out power in lower Manhattan, 160 Water St. is Governor does a ‘180,’ sending its own little ghost town, vacant since seawater filled its basement gambling lobbyists scrambling the night of Oct. 29. But the emptiness of the 24- story building means more than just BY CHRIS BRAGG the absence of tenants like the New York City Health and Hospitals A year ago, Gov. Andrew Cuomo made the centerpiece of his State of Corp. Sliced-off copper cables from the State address an ambitious plan to legalize casino gambling in New the Verizon phone system hang from the telecommunications York. A $4 billion convention center in Queens was to be built next to “frame room” walls, its floor still the Aqueduct racino, which seemed certain to become the city’s first puddled in water. When 160 Water full-fledged casino. In the 2013 iteration of the speech last week, the St. reopens next month, the frame governor reversed himself. He said casinos in the city would under- room will re- mine the goal of drawing Gotham’s 52 million tourists upstate. The main empty. first three gambling venues he eyes for the state now appear destined All the phone 300K for north of the metropolitan area. -

UK £40 USA $65 Simply Abu Dhabi Master Artwork Issue 18 Layout 1 03/05/2015 13:03 Page 126

Simply Abu Dhabi Master Artwork Issue 18_Layout 1 03/05/2015 08:21 Page 1 UK £40 USA $65 Simply Abu Dhabi Master Artwork Issue 18_Layout 1 03/05/2015 13:03 Page 126 oaring 1,005 feet into the skies above Manhattan, One57 has quickly Sbecome one of the most storeyed buildings in all of New York City, if not the world. Located in Manhattan’s bustling midtown epicentre, the allure and success of One57 has coined the term ‘Billionaire’s One57: Row’ as a moniker for the rise of luxury living along the 57th Street Corridor. The The New Standard for vision of prolific developer Gary Barnett, head of Extell Development, One57 exemplifies the very best of what New York has to offer. Aspirational, luxurious, Luxury Living in convenient, and bold, the building is now a recognisable pinnacle in the iconic Manhattan skyline on par with the likes of the Empire State Building, Chrysler New York City Building, and One World Trade Center. With its glistening glass exterior, unparalleled views of Central Park and the Manhattan skyline, expansive floorplans, and unmatched services and amenities, One57 has set the new standard for elevated living in New York. Residents at One57 enjoy around-the-clock access to the exclusive amenities and services of the flagship Park Hyatt New York Hotel located in the base of the building. In addition to preferred seating in the hotel’s acclaimed restaurant The Back Room, residents can arrange for at-home dining services, whether for a romantic dinner for two or a lavish dinner party. -

The Rise of One World Trade Center

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Rise of One World Trade Center Authors: Ahmad Rahimian, Director of Building Structures, WSP Group Yoram Eilon, Senior Vice President, WSP Group Subjects: Architectural/Design Building Case Study Construction Structural Engineering Wind Engineering Keywords: Construction Structural Engineering Wind Loads Publication Date: 2015 Original Publication: Global Interchanges: Resurgence of the Skyscraper City Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Ahmad Rahimian; Yoram Eilon The Rise of One World Trade Center Abstract Dr. Ahmad Rahimian Director of Building Structures One World Trade Center (1WTC) totaling 3.5 mil square feet of area is the tallest of the four WSP Group, buildings planned as part of the World Trade Center Reconstruction at Lower Manhattan in New New York City, USA York City. Currently it is the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere with an overall height of 1776 ft. (541m) to the top of the spire. Ahmad Rahimian, Ph.D., P.E., S.E. F.ASCE, is a Director of Building Structures at WSP. Ahmad’s thirty years of experience with the The 1WTC structural and life safety design set a new standard for design of tall buildings in the firm range from high-rise commercial and residential towers aftermath of the September 11 collapse. The unique site condition with existing infrastructure to major sports facilities. He recently completed the design of 1WTC and One57 W57th Street. His other notable structural also added additional challenges for the design and construction team.