0221-01 Bk.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2 Shape and Space

Volume 2 Shape and Space Colin Foster Introduction Teachers are busy people, so I’ll be brief. Let me tell you what this book isn’t. • It isn’t a book you have to make time to read; it’s a book that will save you time. Take it into the classroom and use ideas from it straight away. Anything requiring preparation or equipment (e.g., photocopies, scissors, an overhead projector, etc.) begins with the word “NEED” in bold followed by the details. • It isn’t a scheme of work, and it isn’t even arranged by age or pupil “level”. Many of the ideas can be used equally well with pupils at different ages and stages. Instead the items are simply arranged by topic. (There is, however, an index at the back linking the “key objectives” from the Key Stage 3 Framework to the sections in these three volumes.) The three volumes cover Number and Algebra (1), Shape and Space (2) and Probability, Statistics, Numeracy and ICT (3). • It isn’t a book of exercises or worksheets. Although you’re welcome to photocopy anything you wish, photocopying is expensive and very little here needs to be photocopied for pupils. Most of the material is intended to be presented by the teacher orally or on the board. Answers and comments are given on the right side of most of the pages or sometimes on separate pages as explained. This is a book to make notes in. Cross out anything you don’t like or would never use. Add in your own ideas or references to other resources. -

Polygons Introduction

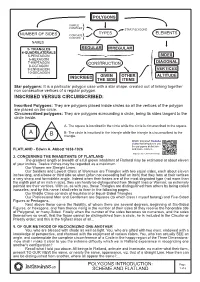

POLYGONS SIMPLE COMPLEX STAR POLYGONS TYPES ELEMENTS NUMBER OF SIDES CONCAVE CONVEX NAMES 3- TRIANGLES REGULAR IRREGULAR 4-QUADRILATERALS 5-PENTAGON SIDES 6-HEXAGON 7-HEPTAGON CONSTRUCTION DIAGONAL 8-OCTAGON 9-ENNEAGON VERTICES 10-DECAGON .... INSCRIBED GIVEN OTHER ALTITUDE THE SIDE ITEMS Star polygons: It is a particular polygon case with a star shape, created out of linking together non consecutive vertices of a regular polygon. INSCRIBED VERSUS CIRCUMSCRIBED: Inscribed Polygons: They are polygons placed inside circles so all the vertices of the polygon are placed on the circle. Circumscribed polygons: They are polygons surrounding a circle, being its sides tangent to the circle inside. A- The square is inscribed in the circle while the circle is circunscribed to the square. A B B- The circle is inscribed in the triangle while the triangle is circumscribed to the triangle. Watch this short Youtube video that introduces you the polygons definition FLATLAND - Edwin A. Abbott 1838-1926 and some names http://youtu.be/LfPDFGvGbqk 3. CONCERNING THE INHABITANTS OF FLATLAND The greatest length or breadth of a full grown inhabitant of Flatland may be estimated at about eleven of your inches. Twelve inches may be regarded as a maximum. Our Women are Straight Lines. Our Soldiers and Lowest Class of Workmen are Triangles with two equal sides, each about eleven inches long, and a base or third side so short (often not exceeding half an inch) that they form at their vertices a very sharp and formidable angle. Indeed when their bases are of the most degraded type (not more than the eighth part of an inch in size), they can hardly be distinguished from Straight lines or Women; so extremely pointed are their vertices. -

Geometry in Design Geometrical Construction in 3D Forms by Prof

D’source 1 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Course Geometry in Design Geometrical Construction in 3D Forms by Prof. Ravi Mokashi Punekar and Prof. Avinash Shide DoD, IIT Guwahati Source: http://www.dsource.in/course/geometry-design 1. Introduction 2. Golden Ratio 3. Polygon - Classification - 2D 4. Concepts - 3 Dimensional 5. Family of 3 Dimensional 6. References 7. Contact Details D’source 2 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Course Introduction Geometry in Design Geometrical Construction in 3D Forms Geometry is a science that deals with the study of inherent properties of form and space through examining and by understanding relationships of lines, surfaces and solids. These relationships are of several kinds and are seen in Prof. Ravi Mokashi Punekar and forms both natural and man-made. The relationships amongst pure geometric forms possess special properties Prof. Avinash Shide or a certain geometric order by virtue of the inherent configuration of elements that results in various forms DoD, IIT Guwahati of symmetry, proportional systems etc. These configurations have properties that hold irrespective of scale or medium used to express them and can also be arranged in a hierarchy from the totally regular to the amorphous where formal characteristics are lost. The objectives of this course are to study these inherent properties of form and space through understanding relationships of lines, surfaces and solids. This course will enable understanding basic geometric relationships, Source: both 2D and 3D, through a process of exploration and analysis. Concepts are supported with 3Dim visualization http://www.dsource.in/course/geometry-design/in- of models to understand the construction of the family of geometric forms and space interrelationships. -

Extremal Axioms

Extremal axioms Jerzy Pogonowski Extremal axioms Logical, mathematical and cognitive aspects Poznań 2019 scientific committee Jerzy Brzeziński, Agnieszka Cybal-Michalska, Zbigniew Drozdowicz (chair of the committee), Rafał Drozdowski, Piotr Orlik, Jacek Sójka reviewer Prof. dr hab. Jan Woleński First edition cover design Robert Domurat cover photo Przemysław Filipowiak english supervision Jonathan Weber editors Jerzy Pogonowski, Michał Staniszewski c Copyright by the Social Science and Humanities Publishers AMU 2019 c Copyright by Jerzy Pogonowski 2019 Publication supported by the National Science Center research grant 2015/17/B/HS1/02232 ISBN 978-83-64902-78-9 ISBN 978-83-7589-084-6 social science and humanities publishers adam mickiewicz university in poznań 60-568 Poznań, ul. Szamarzewskiego 89c www.wnsh.amu.edu.pl, [email protected], tel. (61) 829 22 54 wydawnictwo fundacji humaniora 60-682 Poznań, ul. Biegańskiego 30A www.funhum.home.amu.edu.pl, [email protected], tel. 519 340 555 printed by: Drukarnia Scriptor Gniezno Contents Preface 9 Part I Logical aspects 13 Chapter 1 Mathematical theories and their models 15 1.1 Theories in polymathematics and monomathematics . 16 1.2 Types of models and their comparison . 20 1.3 Classification and representation theorems . 32 1.4 Which mathematical objects are standard? . 35 Chapter 2 Historical remarks concerning extremal axioms 43 2.1 Origin of the notion of isomorphism . 43 2.2 The notions of completeness . 46 2.3 Extremal axioms: first formulations . 49 2.4 The work of Carnap and Bachmann . 63 2.5 Further developments . 71 Chapter 3 The expressive power of logic and limitative theorems 73 3.1 Expressive versus deductive power of logic . -

TOPIC 11 Triangles and Polygons

TOPIC 11 Triangles and polygons We can proceed directly from the results we learned about parallel lines and their associated angles to the ideas concerning triangles. An essential question is a question whose answer is not obvious, but it is a vitally important question that we continue to ponder. Essential question: Why are triangles so important in the study of geometry? We will spend more time studying triangles than any other single topic. Why? Let’s review the definitions: 1. What is a triangle? 2. What is an isosceles triangle? 3. What is an equilateral triangle? 4. What is a scalene triangle? 5. What is a scalene triangle? 6. What is an acute triangle? 7. What is an obtuse triangle? 8. What is a right triangle? Topic 11 (Triangles and Polygons) page 2 What can we discover that is true about a triangle? One well-known result concerns the sum of the angles of a triangle. We will do this with a paper triangle in class … a sort of kinesthetic proof. In a more formal way, we will work through a written proof. Given: Δ ABC Prove: m< 1 + m< 2 + m< 3 = 180 Proof: 1. Draw ECD || AB 1. 2. < 2 ______ 2. 3. < 3 ______ 3. 4. < ____ is supp to < ACD 4. 5. m < ____ + m < ACD = 180 5. Def supp 6. m< 1 +m < ____ = m < ACD 6. angle addition postulate 7. m < 1 + m < ____ + m < ____= 180 7 . 8. m< 1 + m < 2 + m < 3 = 180 8. QED Is the parallel postulate necessary in this proof? (We use this as the parallel postulate: If corresponding angles are congruent, then lines are parallel.) As an implication of this fact, we accept as true the fact that there is only one line through a point which is parallel to a given line. -

Global Insight from Crown Chakra Dynamics in 3D? Strategic Viability Through Interrelating 1,000 Perspectives in Virtual Reality - /

Alternative view of segmented documents via Kairos 8 June 2020 | Draft Global Insight from Crown Chakra Dynamics in 3D? Strategic viability through interrelating 1,000 perspectives in virtual reality - / - Introduction Simpler crown chakra models Design options for a crown chakra with more complex dynamics Framing crown chakra dynamics in relation to symmetrical polyhedra Rendering crown chakra dynamics through interlocking tori Perspectives, projections and learning processes in 3D modelling Cognitive embodiment in the crown chakra? From helicopter to "psychopter": the role of anti-torque? Crown chakra understood as an axial turbofan -- an "attention breathing" jet engine? Balancing duality: objectivity vs subjectivity? Complementarity of pattern languages -- an all-encompassing meta-pattern? Dependence of viable global governance on pattern management? Meta-pattern, Meta-poesis and Music References Introduction The argument for imaginative exploration in 3D of the so-called "1,000-petalled lotus" -- the Crown Chakra or Sahasrara -- was developed in an earlier exercise (Satellite Constellation and Crown Chakra as Complementary Global Metaphors? Experimental representation of crown chakra in virtual reality, 2020). Various models were presented as animations in 3D, illustrated by video and accessible interactively according to the X3D protocol. Subsequent experiment has resulted in the direct presentation of a series of such 3D models in web pages, as indicated separately (Eliciting Insight from Mandala-style Logos in 3D: interactive engagement with mandalas and yantras in virtual reality, 2020). Distinct from the earlier approach, the models were directly interactive rather than requiring plugins or separate operations. The focus there on logos was inspired by the tendency of many organizations, and notably international institutions, to frame their identity through symbolic, mandala-like, imagery in 2D. -

Summary of Introductory Geometry Terminology

MAT104: Fundamentals of Mathematics II Introductory Geometry Terminology Summary Section 11-1: Basic Notions Undefined Terms: Point; Line; Plane Collinear Points: points that lie on the same line Between[-ness]: exactly what the term implies with regard to points [Line] Segment: part of a line consisting of (and named by) two endpoints and all points between them Closed Segment: segment with two included endpoints Half-Open Segment: segment with one included endpoint (also called Half-Closed Segment) Open Segment: segment with no included endpoints Ray: part of a line consisting of one endpoint, a second unique point on the line, all points between them, and all points that have the aforementioned second point between them and the endpoint Half-Line: part of a line on one side of a point on the line (does not include the point) Coplanar: lying on the same plane (points, lines, or parts of lines) Noncoplanar: not coplanar Intersecting Lines: lines with exactly one point in common Skew Lines: lines that cannot be contained in a single plane Concurrent Lines: three or more lines that intersect in the same point Coinciding Lines: identical lines; lines intersecting at every point Parallel Lines: either: a) nonintersecting coplanar lines; or b) two lines that are actually the same line (any line is parallel to itself; coinciding lines as defined above); symbol is Intersecting Planes: planes with exactly one line in common Coinciding Planes: identical planes; planes intersecting at every line Parallel Planes: either: a) nonintersecting planes; or b) two planes that are actually the same plane (any plane is parallel to itself; coinciding planes as defined above) Parallel Line and Plane: a line and plane that either: a) do not intersect in any point; or b) intersect in every point on the line Half-Plane: part of a plane on one side of a line in the plane (does not include the line) Prof. -

Basic Geometry Concepts and Definitions

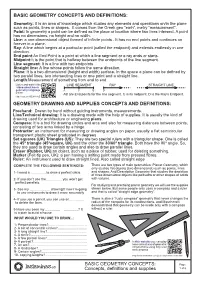

BASIC GEOMETRY CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS: Geometry: It is an area of knowledge which studies any elements and operations on/in the plane such as points, lines or shapes. It comes from the Greek geo “earh”, metry “measurement”. Point: In geometry a point can be defined as the place or location where two lines intersect. A point has no dimensions, no height and no width. Line: a one-dimensional object formed of infinite points . It has no end points and continues on forever in a plane. Ray: A line which begins at a particular point (called the endpoint) and extends endlessly in one direction. End point:An End Point is a point at which a line segment or a ray ends or starts. Midpoint:It is the point that is halfway between the endpoints of the line segment. Line segment: It is a line with two endpoints Straight line: A line whose points follow the same direction. Plane: It is a two-dimensional (height and width) surface. In the space a plane can be defined by two paralel lines, two intersecting lines or one point and a straight line. Length:Measurement of something from end to end Listen and watch this LINE SEGMENT RAY STRAIGHT LINE video about basic geometry language A C B D online AB are End points for the line segment, C is its midpoint. D is the Ray's Endpoint. http://youtu.be/il0EJrY64qE GEOMETRY DRAWING AND SUPPLIES CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS: Freehand: Drawn by hand without guiding instruments, measurements. Line/Technical drawing: It is a drawing made with the help of supplies. -

Polygon and Prism Formulas Shippensburg Area Math Circle Lance & Sarah Bryant, [email protected]

Polygon and Prism Formulas Shippensburg Area Math Circle Lance & Sarah Bryant, [email protected] Math Challenge: Figure out formulas for the construction of polygons and prisms. If you look at a triangle made with the Zome system from far away, it would look like three points and three lines. In fact, it is a good idea to pretend that a zomeball is a point and a strut is a line when we are building, just like they would be if we were drawing shapes on paper. The points and lines that make up polygons and other figures have special names. • A point of a polygon or other figure is called a vertex. The plural of vertex is vertices. • A line of a polygon or other figure is called an edge. Let's see if we can figure out formulas for the number of vertices and edges that polygons have, and then we will consider prisms. Here are some things to try: 1. Use the polygons you have built to fill in the table below. Triangle Square Pentagon Hexagon Decagon Number of Vertices Number of Edges 2. A chiliagon has 1,000 sides. How many vertices does it have? How many edges? 3. If an n-gon has n sides, then how many vertices does it have? How many edges? 4. Alright, the answers you got in #3 are called formulas. You can replace n with a number, for example 5, and then see how many edges a 5-gon (or pentagon) has. Try it! Does it match the answer in the table from #1? This document is based on material from Zome Geometry by Hart and Picciotto. -

Name: Date: WORKSHEET : Polygons a Polygon Is a Closed, Planar

Name: Date: WORKSHEET : Polygons A polygon is a closed, planar shape connected by straight lines. Polygons can be categorized as regular or irregular. Polygons can be categorized as convex or concave. Polygons can be categorized as simple or complex. WORKSHEET : Polygons Interior/Exterior Angles ANSWERS : Polygons Interior/Exterior Angles KEY CONCEPTS: Definition of polygons and interior/exterior angle measures. 1. A polygon is a closed, planar shape connected by straight lines. a. Not closed ≠ polygon b. Not all straight lines ≠ polygon c. Planar means it is 2 dimensional; on an x-y coordinate plane for example d. Definitions of terms i. Vertex = The point where two lines meet on the polygon ii. Interior Angle = The angle inside the polygon between adjacent sides iii. Exterior Angle = If a line is extended from one side of the polygon past the vertex then the exterior angle is the angle between that line and the next adjacent side. 2. Names of polygons depend on the number of sides or interior angles (the same value). The smallest number of sides for a two dimensional polygon is 3. As n approaches infinity the polygon approaches a circle, but a circle is not a polygon due to its curves. Number of Sides, (n) Polygon Name 3 Triangle 4 Quadrilateral 5 Pentagon 6 Hexagon 7 Septagon(or Heptagon) 8 Octagon 10 Decagon 12 Dodecagon 15 Pentadecagon 100 Hecatgon 1,000 Chiliagon 1,000,000 Megagon 10100 Googolgon 3. The sum of interior angles of any n-sided polygon is... Sum Interior Angles = 180(n - 2) expressed in degrees e.g. -

Polygon from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Polygon (Disambiguation)

Polygon From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Polygon (disambiguation). In elementary geometry, a polygon /ˈpɒlɪɡɒn/ is a plane figure that is bounded by a finite chain of straight line segments closing in a loop to form a closed chain or circuit. These segments are called its edges or sides, and the points where two edges meet are the polygon's vertices (singular: vertex) or corners. The interior of the polygon is sometimes called its body. An n-gon is a polygon with n sides. A polygon is a 2-dimensional example of the more general polytope in any number of dimensions. Some polygons of different kinds: open (excluding its The basic geometrical notion of a polygon has been adapted in various ways to suit particular purposes. boundary), bounding circuit only (ignoring its interior), Mathematicians are often concerned only with the bounding closed polygonal chain and with simple closed (both), and self-intersecting with varying polygons which do not self-intersect, and they often define a polygon accordingly. A polygonal boundary may densities of different regions. be allowed to intersect itself, creating star polygons. Geometrically two edges meeting at a corner are required to form an angle that is not straight (180°); otherwise, the line segments may be considered parts of a single edge; however mathematically, such corners may sometimes be allowed. These and other generalizations of polygons are described below. Contents 1 Etymology 2 Classification 2.1 Number of sides 2.2 Convexity and non-convexity 2.3 Equality -

Basic Geometry Concepts and Definitions

BASIC GEOMETRY CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS: Geometry: It is an area of knowledge which studies any elements and operations on/in the plane such as points, lines or shapes. It comes from the greek geo “earh”, metry “measurement”. Point: In geometry a point can be defined as the place or location where two lines intersect. A point has no dimensions, no height and no width. Line: a one-dimensional object formed of infinite points . It has no end points and continues on forever in a plane. Ray: A line which begins at a particular point (called the endpoint) and extends endlessly in one direction. End point:An End Point is a point at which a line segment or a ray ends or starts. Midpoint:It is the point that is halfway between the endpoints of the line segment. Line segment: It is a line with two endpoints Straight line: A line wich all its points follow the same direction. Plane: It is a two-dimensional (height and width) surface. In the space a plane can be defined by two paralel lines, two crossing lines or one point out of a straight line. Length:Measurement of something from end to end Listen and watch this LINE SEGMENT RAY STRAIGHT LINE video about basic geometry language A C B A online AB are End points for the line segment, C is its midpoint. D is the Ray's Endpoint. http://youtu.be/il0EJrY64qE GEOMETRY DRAWING AND SUPPLIES CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS: Freehand: Drawn by hand without guiding instruments, measurements. Line/Thechincal drawing: It is a drawing made with the help of supplies.