Pilbara Steer Growth Evaluation : 1994 - 1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing the Pilbara Department of a Prefeasibility Assessment of the Potential Primary Industries and Regional Development for Irrigated Agriculture Development

Growing the Pilbara Department of A prefeasibility assessment of the potential Primary Industries and Regional Development for irrigated agriculture development Growing the Pilbara — A prefeasibility assessment of the potential for irrigated agriculture development 1 November 2017 Disclaimer The Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development and the State of Western Australia accept no liability whatsoever by reason of negligence or otherwise arising from the use or release of this information or any part of it. © Western Australian Agriculture Authority, 2017 3 Baron-Hay Court, South Perth WA 6151 Tel: (08) 9368 3333 Email: [email protected] dpird.wa.gov.au COVER (MAIN): Photo courtesy: Nathon Dyer RIGHT: Photo courtesy: Nathon Dyer Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Growing the Pilbara A prefeasibility assessment of the potential for irrigated agriculture development A Pilbara Hinterland Agricultural Development Initiative Growing the Pilbara — A prefeasibility assessment of the potential for irrigated agriculture development 3 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................... 6 Water resources ........................................................... 25 Executive summary ...................................................... 8 Groundwater ............................................................... 25 Introduction ................................................................... 10 Targeted aquifers ....................................................... -

Roy Hill, Western Australia (1:250 000 Geological Series Explanatory Notes)

WESTERN AUSTRALIA SECOND EDITION A s. , . -. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 1:250 000 GEOLOGICAL SERIES-EXPLANATORY NOTES ROY HILL WESTERN AUSTRAL SECOND EDITION SHEET SF50-12 INTERNATIONAL INDEX by A. M. THORNE AND I. M. TYLER Perth. Western Australia 1997 MINISTER FOR MINES The Hon. Norman Moore, MLC ACTING DIRECTOR GENERAL L. C. Ranford DIRECTOR, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Pietro Guj Copy editor: A. George REFERENCE The recommended reference for this publication is: THORNE, A. M., and TYLER, I. M., 1997, Roy Hill, W.A. (2nd Edition): 1:250 000 Geological Series Explanatory Notes, 22p. ISSN 0729-3720 National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0 7309 6556 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 PILBARA CRATON GRANITE-GREENSTONE ROCKS .............................................. 2 Serpentinite and tremolite-chlorite schist (ALL)............................................................... 2 Metamorphosed basalt (Ah) and pyroxene spinifex-textured basalt (Abnz) .................... 3 Metagabbro and hornblende schist (Aog) ....................................................................... 4 Schist derived from igneous rocks (AE) ........................................................................... 4 Banded iron-formation (Aci) ........................................................................................... 5 Metamorphosed granitoid rocks 5 Kurrana Granitoid Complex ( ........................................................................ -

ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES of the GASCOYNE-ASHBURTON REGION Peter Austin 1

ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES OF THE GASCOYNE-ASHBURTON REGION Peter Austin 1. INTRODUCTION1 This paper is a description of the language situation in the region between the Gascoyne and Ashburton Rivers in the north-west of Western Australia. At the time of first white settlement in the region, there were eleven languages spoken between the two rivers, several of them in a number of dialect forms. Research on languages of the locality has taken place mainly in the past thirty years, after a long period of neglect, but details of the past and present linguistic situation have been emerging as a result of that research. The paper includes an annotated bibliography of the Aboriginal languages traditionally spoken in the area 2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The first explorations by Europeans in the north-west of Western Australia were maritime voyages concerned with coastal exploration. As early as 1818, Captain P.P. King had reported on the coast east of Exmouth Gulf and between 1838 and 1841 Captains Wickham and Stokes had discovered the mouth of the Ashburton River (Webb & Webb 1983:12). On 5th March 1839 Lieutenant George Grey came upon the mouth of the Gascoyne River and during his explorations encountered Aborigines. He reported that (Brown 1972:83): “they spoke a dialect very closely resembling that of the natives of the Swan River”. Further contact between Gascoyne-Ashburton language speakers and Europeans came in the 1850’s with inland explorations. In 1858 Francis Gregory explored the Gascoyne River and the Lyons River north as far as Mount Augustus (Green 1981:97-8, Webb & Webb 1983:11, Brown 1972:86). -

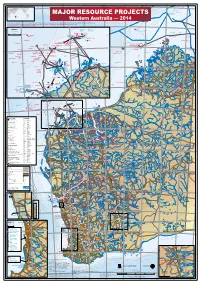

Major-Resource-Projects-Map-2014.Pdf

112° 114° 116° 118° 120° 122° 124° 126° 128° 10° 10° JOINT PETROLEUM DEVELOPMENT AREA MAJOR RESOURCE PROJECTS Laminaria East Western Australia — 2014 Major projects operating or under development in 2013 with an actual/anticipated value of annual production of greater than $A10 million are shown in blue NORTHERN TERRITORY Proposed or potential major projects with a capital expenditure estimated to be greater than $A20 million are shown in red WESTERN AUSTRALIA Care and maintenance projects are shown in purple 114° 116° m 3000 Ashmore Reef West I 12° Mutineer East I INSET A Fletcher Middle I 2000 m 2000 12° Exeter Finucane TERRITORY OF ASHMORE SCALE 1:1 200 000 AND CARTIER ISLANDS INDONESIA Lambert Deep AUSTRALIA T I M O R S E A 50 km Eaglehawk Hermes Larsen Deep Egret Lambert Noblige Searipple Athena SHELF Angel Prometheus Montague m 1000 Larsen Capella Petrel Perseus Persephone Cossack Wanaea Forestier Ajax North Rankin COMMONWEALTH 'ADJACENT AREAS' BOUNDARY Chandon Gaea Hurricane Frigate Tern Keast Goodwyn Goodwyn S/Pueblo Holothuria Reef Echo/Yodel Crown Trochus I Yellowglen Rankin/Sculptor Tidepole Mimia Dockrell Kronos Concerto/Ichthys Cornea Otway Bank Urania Troughton I Io Pemberton WEST Echuca Shoals Cape Londonderry Dixon/W.Dixon Ichthys West SIR GRAHAM Cape Wheatstone Prelude MOORE Is Ta lb ot Sage Parry HarbourTroughton Passage Lesueur I Ichthys Eclipse Is Jansz Pluto Cassini I Cape Rulhieres Iago Saffron Torosa Mary I Geryon Eris 20° Browse I Oyster Rock Passage Vansittart NAPIER Blacktip Bay BROOME Io South Reindeer Cape -

Major Resource Projects, Western Australia

112° 114° 116° 118° 120° 122° 124° 126° 128° 10° 10° JOINT PETROLEUM MAJOR RESOURCE PROJECTS DEVELOPMENT AREA Western Australia — 2021 Principal resource projects operating with sales >$5 million in 2019–20 are in blue text NORTHERN TERRITORY WESTERN AUSTRALIA Resource projects currently under construction are in green text m 3000 Planned mining and petroleum projects with at least a pre-feasibility study (or equivalent) completed are in red text Principal resource projects recently placed on care and maintenance, or shut are in purple text Ashmore Reef West I East I 12° 114° 116° Middle I 2000 m 2000 TERRITORY OF ASHMORE 12° INSET A AND CARTIER ISLANDS T I M O R S E A SCALE 1:1 200 000 50 km Hermes Lambert Athena m 1000 Angel Searipple Persephone Cossack INDONESIA Perseus Wanaea AUSTRALIA North Rankin SHELF COMMONWEALTH 'ADJACENT AREAS' BOUNDARY Chandon Goodwyn Holothuria Reef Keast Trochus I Sculptor Tidepole Dockrell Pyxis Lady Nora Pemberton Prelude Troughton I Cape Londonderry SIR GRAHAM Cape Wheatstone Talbot Ichthys Parry HarbourTroughton Passage MOORE IS Lesueur I Jansz–Io Eclipse Is Pluto Cassini I Cape Rulhieres WEST Mary I Iago Torosa NAPIER 20° Browse I Oyster Rock Passage Vansittart Xena BROOME Blacktip Bay Scott Reef Fenelon I BAY 200 m 200 Yankawinga I Reindeer Kingsmill Is 14° Cone Mountain RIVER JOSEPH BONAPARTE 14° Brunello Brecknock Maret Is Prudhoe Is MONTAGUE ADMIRALTY GULF 20° Chrysaor/Dionysus Turbin I SOUND GULF Reveley I Calliance Warrender Hill RIVER Carson River Buckle Head Wandoo GEORGE BIGGE I Mt Connor Mt -

1:100 000 Geological Maps

1:100 000 GEOLOGICAL MAPS Revision in progress LONDONDERRY SD 52-5 Map and Explanatory Notes TROUGHTON LONDONDERRY RUHLIERES 4170 4270 4370 Map ADMIRALTY KING MARET MONTALIVET GULF VANSITTART DRYSDALE GEORGE CASUARINA 3869 3969 4069 4169 4269 4369 4469 MONTAGUE SOUND DRYSDALE MEDUSA BANKS Digital data (captured from existing map) SD 51-12 SD 52-9 SD 52-10 BUFFON BIGGE WARRENDER KING EDWARD CARSON COLLISON BERKELEY MEDUSA KNOB PEAK 3868 3968 4068 4168 4268 4368 4468 4568 4668 Digital data (no map planned) PRINCE CHAMPAGNY BRUNSWICK FREDERICK BRADSHAW COUCHMAN ASHTON ERNEST MILLIGAN WYNDHAM CARLTON 3767 3867 3967 4067 4167 4267 4367 4467 4567 4667 Map/Digital data in preparation/progress CAMDEN SOUND PRINCE REGENT ASHTON CAMBRIDGE GULF SD 51-15 SD 51-16 SD 52-13 SD 52-14 COCKELL METHUEN PRINCE HANN WOODHOUSE CAMM BEATRICE PENTECOST ERSKINE KUNUNURRA REGENT 3866 4066 4166 4266 4366 4466 4566 4666 Fieldwork planned 3766 3966 16° DUNHAM ARGYLE ANZAC SHOAL SUNDAY YAMPI COLLIER BAY ELGEE LEVEQUE ISLAND WALCOTT EDKINS JAMESON GIBB SULLIVAN KARUNJIE RIVER DOWNS Geoscience Australia map and 3365 3465 3565 3665 3765 3865 3965 4065 4165 4265 4365 4465 4565 4665 Explanatory Notes PENDER YAMPI CHARNLEY MOUNT ELIZABETH LISSADELL SE 51-2 SE 51-3 SE 51-4 PACKHORSE SE 52-1 SE 52-2 BALEINE LACEPEDE PENDER CORNAMBIE KIMBOLTON TARRAJI MATTHEW ISDELL RANGE BARNETT SIDDINS SALMOND CHAMBERLAIN BOW LISSADELL Geoscience Australia map 3264 3364 3464 3564 3664 3764 3864 3964 4064 4164 4264 4364 4464 4564 4664 MOUNT TURKEY RICHENDA MOUNT Explanatory Notes in: Report -

Mineralization and Geology of the Bangemall Basin

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA REPORT 64 PLATE 1 Fortescue Roadhouse 130 km MINERAL OCCURRENCES OF THE BANGEMALL BASIN MINERAL OCCURENCES ADJACENT TO THE BANGEMALL BASIN REFERENCE 115¾30À å50 GEOLOGICAL SETTING NUMBER COM NUMBER NUMBER NUMBER CARNARVON MODITY EASTING NORTHING NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING NAME PILBARA CRATON ìg BASIN CANNING CAINOZOIC REGOLITH OVERPRINTS These examples are shown over ñg colour PRECIOUS MINERALÝ_ÝDmd, Vrs 84 Cu Pb (Ag) 467966 7339946 Kurabuka Creek PRECIOUS MINERALÝ_ÝAmet, Clc, Dmd, Tur 1463 Pb (Ag Au) 493189 7411266 AnticlineÝ_ÝBali Hi ìl CANNING BASIN BASIN Y 86 Cu Pb (Ag) 364682 7399260 Latham 1465 Cu 494891 7411575 Bali High East ìW YENEENA BASIN Kimberlite and lamproite diatremes 87 Cu Pb (Ag) 374315 7428268 Joy Helen Pegmatitic 1528 Cu 350749 7384085 High Range (Cu) CAPRICORN FORMATION: conglomerate, ferruginous and quartzitic sandstone, ferruginous 1531 Depositional _ colluvial, sheetwash, alluvial, lacustrine, eolian, and related calcrete deposits ìr siltstone and mudstone, dolostone, and felsic volcanic rock HIGHWA 3003 Dmd 390650 7410950 88 Cu 364292 7509074 Warrada Creek 2949 Amet Clc Tur 445957 7292485 Gascoyne Amethyst (Soklich) Cu Pb Zn 355236 7381186 High Range (Zn) 240 Cu Pb (Ag) 386920 7407800 1558 Cu 372453 7359256 Star Of Mangaroon South Hamersley Basin Vein and hydrothermalÝ_Ýundivided SedimentaryÝ_Ýalluvial to beach placers 296 Pb (Ag) 758928 7326734 Keep-It-Dark 1559 Pb (V) 372542 7359335 RUDALL COMPLEX 2946 -

Looking West: a Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia

A Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia The Records Taskforce of Western Australia ¨ ARTIST Jeanette Garlett Jeanette is a Nyungar Aboriginal woman. She was removed from her family at a young age and was in Mogumber Mission from 1956 to 1968, where she attended the Mogumber Mission School and Moora Junior High School. Jeanette later moved to Queensland and gained an Associate Diploma of Arts from the Townsville College of TAFE, majoring in screen printing batik. From 1991 to present day, Jeanette has had 10 major exhibitions and has been awarded four commissions Australia-wide. Jeanette was the recipient of the Dick Pascoe Memorial Shield. Bill Hayden was presented with one of her paintings on a Vice Regal tour of Queensland. In 1993 several of her paintings were sent to Iwaki in Japan (sister city of Townsville in Japan). A recent major commission was to create a mural for the City of Armadale (working with Elders and students from the community) to depict the life of Aboriginal Elders from 1950 to 1980. Jeanette is currently commissioned by the Mundaring Arts Centre to work with students from local schools to design and paint bus shelters — the established theme is the four seasons. Through her art, Jeanette assists Aboriginal women involved in domestic and traumatic situations, to express their feelings in order to commence their journey of healing. Jeanette currently lives in Northam with her family and is actively working as an artist and art therapist in that region. Jeanette also lectures at the O’Connor College of TAFE. Her dream is to have her work acknowledged and respected by her peers and the community. -

QON LC 1875 – Pastoral Leases

QON LC 1875 – Pastoral leases Station Name Lease Total Station Name Lease Total Number Station Number Station Area (ha) Area (ha) ADELONG N050386 108,793 BOODARIE N050445 64,620 ALBION DOWNS N049530 140,509 N050447 9,694 ALICE DOWNS N050018 136,974 BOOGARDIE N050334 161,073 ANNA PLAINS N050392 392,324 BOOLARDY N049598 333,964 ANNEAN N050577 163,909 BOOLATHANA N050616 143,264 N050578 25,531 BOOLOGOORO N050380 3,667 ARUBIDDY N049537 314,394 N050381 65,272 ASHBURTON N050036 311,235 BOONDEROO N050420 308,923 DOWNS BOOYLGOO N050557 233,339 ATLEY N050586 353,558 SPRING AUSTIN DOWNS N050063 162,917 BOW RIVER N049619 300,878 AVOCA DOWNS N049885 121,392 BRAEMORE N049916 13,255 BADJA N049542 113,653 BRICK HOUSE N050631 224,243 BALFOUR N049548 85,926 BROOKING N050173 10,615 DOWNS N049553 345,254 SPRINGS N050174 183,258 BALGAIR N049892 289,316 BRYAH N049600 122,689 BALLADONIA N050098 46,266 BULGA DOWNS N050442 273,949 N050099 175,878 BULKA N050503 274,749 BALLYTHUNNA N050597 124,556 BULLABULLING N049612 94,038 BANJAWARN N050400 406,813 BULLARA N050158 109,501 BARRAMBIE N049557 100,564 BULLARDOO N049633 41,942 BARWIDGEE N049559 276,396 BULLOO DOWNS N049943 40,6489 BEDFORD N050413 376,963 BUNNAWARRA N049947 90,154 DOWNS BURKS PARK N049650 8,133 BEEBYN N049894 59,815 BUTTAH N049656 147,843 BEEFWOOD PARK N050113 14,831 BYRO N050480 237,872 N050132 21,535 CALLAGIDDY N050519 65,380 N050147 169,189 CALOOLI N050390 12,383 BELELE N049563 279,705 CARBLA N050530 95,193 BERINGARRA N050464 140,323 CARDABIA N049635 193,753 BIDGEMIA N050619 372,375 CAREY DOWNS N049938 -

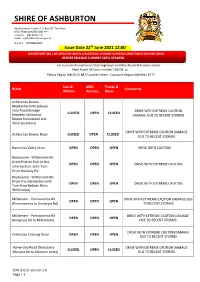

SOA IS 013 Version 1.0 Page | 1 Hamersley Road (Solomon Entry DRIVE with EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE CLOSED OPEN CLOSED to Rio Rail Access Road) DUE to RECENT STORMS

SHIRE OF ASHBURTON Administration Centre. P.O. Box 567, Tom Price, 6751 Telephone (08) 9188 4444 Facsimile (08) 9189 2252 Email: [email protected] Our Ref: 1847898/RD09 Issue Date 22th June 2021 12:00 THIS REPORT WILL BE UPDATED WHEN A MATERIAL CHANGE IN ROAD CONDITIONS OCCURS ROAD REPORT REMAINS CURRENT UNTIL UPDATED For current information on State Highways and Main Roads WA roads contact Main Roads All hours number 138138, or Pilbara Region (08) 9172 8877 and Mid West - Gascoyne Region (08) 9941 0777 Cars & 4WD Trucks & ROAD Comments Utilities Vehicles Buses Ashburton Downs - Meekatharra Rd (please note flood damage DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION CLOSED OPEN CLOSED between Ashburton DAMAGE DUE TO RECENT STORMS Downs homestead and Shire boundary) DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE Ashburton Downs Road CLOSED OPEN CLOSED DUE TO RECENT STORMS Nameless Valley Drive OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH CAUTION Roebourne - Wittenoom Rd (from Python Pool to the OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION intersection with Tom Price Railway Rd Roebourne - Wittenoom Rd (from the intersection with OPEN OPEN OPEN DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION Tom Price Railway Rd to Wittenoom) Millstream - Pannawonica Rd DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE DUE OPEN OPEN OPEN (Pannawonica to Kanjenjie Rd) TO RECENT STORMS Millstream - Pannawonica Rd DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE OPEN OPEN OPEN (Kanjenjie Rd to Millstream) DUE TO RECENT STORMS DRIVE WITH EXTREME CAUTION DAMAGE Fortescue Crossing Road OPEN OPEN OPEN DUE TO RECENT STORMS Hamersley Road (Nanutarra- DRIVE WITH -

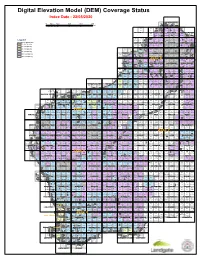

(DEM) Coverage Status Index Date : 22/05/2020

Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Coverage Status Index Date : 22/05/2020 LONDONDERRY 0 62.5 125 250 375 500 4070 4170 4270 4370 km LONG REEF TROUGHTON LONDONDERRY RULHIERES 3669 3869 3969 4069 4169 4269 4369 4469 BROWSE MARET MONTALIVET ADMIRALTY GULF VANSITTART DRYSDALE KING GEORGE CASUARINA BROWSE ISLANDMONTAGUE SOUND DRYSDALE MEDUSA BANKS 3868 3968 4068 4168 4268 4368 4468 4568 4668 BUFFON BIGGE WARRENDER KING EDWARD CARSON COLLISON BERKELEY MEDUSA KNOB PEAK 3567 3667 3767 3867 3967 4067 4167 4267 4367 4467 4567 4667 BRUNSWICK Legend FRASER INLET BEAGLE REEF CHAMPAGNY BRADSHAW COUCHMAN ASHTON ERNEST MILLIGAN WYNDHAM CARLTON PRINCE FREDERICK DEM_USED_FOR_RECTIFICATION CAMDEN SOUND PRINCE REGENT ASHTON CAMBRIDGE GULF 1m Grid Spacing 3566 3666 3766 3866 3966 4066 4166 4266 4366 4466 4566 4666 ADELE MACLEAY COCKELL METHUEN PRINCE REGENT HANN WOODHOUSE CAMM BEATRICE PENTECOST ERSKINE KUNUNURRA 2m Grid Spacing 3m Grid Spacing 3365 3465 3565 3665 3765 3865 3965 4065 4165 4265 4365 4465 4565 4665 ANZAC SHOAL LEVEQUE SUNDAY ISLAND YAMPI COLLIER JAMESON GIBB SULLIVAN KARUNJIE ELGEE DUNHAM ARGYLE DOWNS 5m Grid Spacing WALCOTT EDKINS PENDER YAMPI 3864 CHARNLEY4064MOUNT ELIZABETH LISSADELL 10m Grid Spacing 3264 3364 3464 3564 3664 3764 3964 4164 4264 4364 4464 4564 4664 MATTHEW ISDELL PACKHORSE Rg. 20m Grid Spacing BALEINE LACEPEDE PENDER CORNAMBIE KIMBOLTON TARRAJI BARNETT SIDDINS SALMOND CHAMBERLAIN BOW LISSADELL 3363 3463 3563 3663 3763 3Z863 on396e3 64063 4163 4263 4363 4463 4563 4663 Mt. REMARKABLE CARNOT JOWLAENGA FRASER DERBY MEDA GLENROY TABLELAND -

A Report on the Viability of Pastoral Leases in the Northern Rangelands Region Based on Biophysical Assessment

A Report on the Viability of Pastoral Leases in the Northern Rangelands Region Based on Biophysical Assessment Dr PE Novelly - South Perth Mr D Warburton - Northam 7 September 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Kimberley and Pilbara comprise Western Australia’s Northern Rangelands. The pastoral industry of both regions is becoming increasingly similar, with most formerly sheep producing properties in the Pilbara moving to cattle, more control and manipulation of herds, and enterprises with a higher proportion of breeders. The projected viability (based on a capacity to carry a minimum number of stock in an ecologically sustainable manner) of pastoral leases in this region was analysed through assessment of biophysical parameters, in particular the inherent landscape productivity and its capacity to be managed in an ecologically sustainable manner, and the impact of current rangeland condition on grazing capacity. Analysis was conducted on individual pastoral leases The effect of leases being run in combination with other leases in one business, or access to substantial non-pastoral income was ignored. Of the 154 pastoral leases assessed, applying a threshold viability level of a potential carrying capacity of 4,000 cattle units, but ignoring reduced carrying capacity caused by degraded rangeland condition: • 16 leases in the Kimberley and 37 leases in the Pilbara do not reach the viability threshold when all land systems within the lease area are considered; • 18 Kimberley leases and 40 Pilbara leases do not meet the viability threshold when land systems whose pastoral potential is so low that investment in management and infrastructure is considered non-viable are excluded. The background and arguments behind this assessment are discussed.