The Sister Chapel an Essential Feminist Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LONG ISLAND ARTISTS: Focus on Matt:}"Ials, Our Second Special Rhonda Cooper Exhibition Featuring Long Island Artists

wto• •:1 ••• 'l)I (IQU.4 !N" Utlfll r. 1\ '-'•1fl"!t••l"9'itQ IN"'° • ••• ,., •1•e.t)I .. "'"•)t'• ,....... • LONG ISLAND ARTISTS Focus On Materials STAN.BRODSKY SARA » 'ALESSANDRO LILLIAN DODSON BEVERLY F.LIAS FIGEL TEMIMA GEZARL SYLVIA BARNICK WOODY HUGHES KATHLEEN KUCKA SEUNG LEE BRUCE LIEBERMAN (\ATINKA MANN NORMAN MERCER MAUREEN PAC:MIERJ RICHARD RE'UTER ARLEEN SCHATZ KAREN SHA JULIE SMALL--CAMBY DAN WELDEN.: f.EL}CITAS WETIER June 13 • ~ 1, 1998 STAN BRODSKY "We explore form for the sake of express ion and for the insight it can give us into our own soul." (Paul Klee) I value that sensibility which desires to disclose 011e 's i11ner core. In my work, internalized ex periences, modulated principally through color, dictate a subjective response to landscape. /11 painting, I seek to assert my essemial nature. Naucclle # 13, 1997 Oil and paint stick on canvas. 54. 44" Councsy June Kelly Gallery. NYC Photo creclil: 0 1997 Ji m Sirong. Hempstead. NY SARA D' ALESSANDRO Sculpting with my id in the tips of my fingers, I am not certain whether I form the clay or the clay forms me. Mud is the thixotrophy from which these forms arise. They are organic, conveying mortality and allowing glimpses into the mystery of creation. Teeming with texture, extremely respo11sive to light, the history ofprocess is visible for all those who care to see. Earth Tongue. 1996 Terra coua unique. 66" high LILLIAN DODSON I'm continually carving a path by being in touch with self, trusting intuition, and using reference from life. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 13 American Artists: a Celebration Of

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 13 American Artists: A Celebration of Historic Work April 29 - June 26, 2021 Eric Firestone Gallery 40 Great Jones Street |New York, NY Featuring work by: Elaine Lustig Cohen |Charles DuBack | Martha Edelheit | Shirley Gorelick Mimi Gross | Howard Kanovitz | Jay Milder | Daphne Mumford | Joe Overstreet | Pat Passlof | Reuben Kadish | Miriam Schapiro | Thomas Sills Charles Duback | Adam and Eve, 1970 |acrylic, wood and felt on canvas | 96h x 120w in In honor of our first season in a new ground floor space at 40 Great Jones Street, Eric Firestone Gallery presents 13 American Artists, an exhibition showcasing artists from the gallery’s unique, wide-ranging historical program. The gallery has made central a mission to explore the ever-expanding canon of Post-World War II American art. Over the last several years, the gallery has presented major retrospectives to champion artists whose stories needed to be re-told. Their significant contributions to art history have been further reinforced by recent institutional acquisitions and exhibitions. 13 American Artists celebrates this ongoing endeavor, and the new gallery, presenting several artists and estates for the first time in our New York City location. EAST HAMPTON NYC 4 NEWTOWN LANE 40 GREAT JONES STREET EAST HAMPTON, NY 11937 NEW YORK, NY10012 631.604.2386 646.998.3727 Shirley Gorelick (1924-2000) is known for her humanist paintings of subjects who have traditionally not been heroized in large-scale portraiture. Gorelick, like most artists in this exhibition, forged her career outside of the mainstream art world. She was a founding member of Central Hall Artists Gallery, an all-women artist-run gallery in Port Washington, New York, and between 1975 and 1986, had six solo exhibitions at the New York City feminist cooperative SOHO20. -

Download Issue (PDF)

Vol. 2 No. 2 wfimaqartr f l / l I l U X l U l I Winter 1977-78 ‘ARTISTS IN RESIDENCE': The First Five Years Five years ago, the A.I.R. feminist co-op gallery opened its doors, determined to make its own, individual mark on the art world. The first co-op organized out of the women artists' movement, it continues to set high standards of service and commitment to women's art by Corinne Robins page 4 EXORCISM, PROTEST, REBIRTH: Modes ot Feminist Expression in France Part I: French Women Artists Today by Gloria Feman Orenstein.............................................................page 8 SERAPHINE DE SENLIS With no formal art training, she embarked on a new vocation as visionary painter. Labelled mentally ill in her own time, she is finally receiving recognition in France for her awakening of 'female creativity' by Charlotte Calmis ..................................................................... p a g e 12 A.I.R.'S FIFTH ANNIVERSARY 1 ^ ^ INTERVIEW WITH JOAN SEMMEL W omanart interviews the controversial contemporary artist and author, curator of the recent "Contemporary Women: Consciousness and Content" at the Brooklyn Museum by Ellen L u b e ll.................................................................................page 14 TOWARD A NEW HUMANISM: Conversations with Women Artists Interviews with a cross-section of artists reveal their opinions on current questions and problems, and how these indicate movement toward a continuum of human values by Katherine Hoffman ................................................................... pa g e 22 GALLERY REVIEWS ..........................................................................page 30 WOMAN* ART»WORLD News items of interest ................................................................... page 42 FRENCH WOMEN ARTISTS REPORTS Lectures and panel discussions accompany "Women Artists: 1550-1950" and "Contemporary Women" at the Brooklyn Museum; Women Artists in H o lla n d ...............................................................page 43 Cover: A.I.R. -

A Finding Aid to the Dorothy Gees Seckler Collection of Sound Recordings Relating to Art and Artists, 1962-1976, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Dorothy Gees Seckler Collection of Sound Recordings Relating to Art and Artists, 1962-1976, in the Archives of American Art Megan McShea Funding for the transcription of Seckler's interviews with Provincetown artists was provided by the Shirley Gorelick Foundation in 2014. 2015 May 27 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Interviews with Artists, 1962-1976............................................................ 6 Series 2: Broadcast Materials, 1962 - circa 1972................................................. -

Women Defining Themselves the Original Artists of SOHO 20

Rowan University Art Gallery Select Exhibitions Jamea Richmond-Edwards: 7 Mile Girls Ebony G. Patterson: If We Must Die… November 7 – December 21, 2019 February 11 - April 20, 2019 The title 7 Mile Girls refers to the street in Detroit Known for her drawings, tapestries, videos, sculptures where Richmond-Edwards grew up the late 1980s and and installations that involve surfaces layered with early ’90s and where she encountered many of the flowers, glitter, lace and bead, Ebony G. Patterson’s female subjects depicted in her paintings. This works investigate forms of embellishment as they relate exhibition explores the connection between black to youth culture within disenfranchised communities. In female style of Detroit’s inner city with designer fashion conjunction with the exhibit, a conversation with the and self-empowerment. Across her multi-layered artist was held on Wednesday, March 27 at 5:00 p.m. in collages, the artist expresses the intersections of black the gallery, led by visiting scholar Colette Gaiter, a style, capitalism, fashion, and personal identity. professor in the Department of Art & Design and View the Exhibition Catalog Department of Africana Studies at the University of Delaware. Julie Heffernan: Mending a Reflection September 3 – October 26, 2019 Heather Ujiie: Terra Incognita September 4 – November 17, 2018 Mending a Reflection addresses the connection between culture, mass media and personal identity Heather Ujiie blends the disciplines of textiles, fashion through the lens of one dominate central female figure. design, and visual art to create an ethereal, imaginary In her large-scale self-portraits Heffernan investigates and mythological world. -

SBU Art Exhibition, Gallery & Museum Spaces

SBU Archives: SBU Art Exhibition, Gallery & Museum Spaces Start Date End Date Event Title Artist(s): Last, First Location (from Catalog) Lom, Kiana; Schnell, Blake; Tabora, 2021-04-29 2021-05-19 Senior Show & URECA Art Exhibition 2021 Kevin; Calle, Nikola; Wang, Xiaohui Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Balius, Stuart; Cheng, Yifei; Baumiller, 2021-03-22 2021-04-16 Four: MFA Thesis Exhibition 2021 Marta; Waugh, Annemarie Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2021-02-01 2021-03-01 Reckoning: Student Digital Mural Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University (Online) 2020-10-01 2021-10-31 Reckoning: Faculty Exhibition 2020 Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University (Online) 2020-04-30 2020-05-22 Senior Show and URECA Art Exhibition Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2020-03-21 2020-04-18 MFA Thesis Exhibition 2020: Presence Absence Miller, Julia; Santarpia, Joseph Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Artists As Innovators: Celebrating Three Decades of 2019-10-26 2020-02-22 NYSCA/NYFA Fellowships Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2019-07-18 2019-10-12 View from Here: Contemporary Perspectives From Senegal, The Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University 2019-05-02 2019-05-15 Senior Show and URECA Art Exhibition Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Ruiz, Lauren; Avolio, Maggie; Kaiser, 2019-03-23 2019-04-18 MFA Thesis Exhibition 2019: Fold, Fragment, Forum Katherine Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery, Stony Brook University Gannis, Carla; Leegte, Jan Robert; Louw, Gretta; Matsuda, Keiichi; Mundy, Owen; Rezaire, Tabita; Ross, Alicia; 2019-01-26 2019-02-23 Iconicity Warnayaka Art Centre; American Artist Paul W. -

Download Issue (PDF)

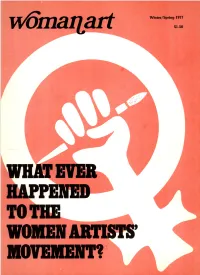

Vol. 1 No. 3 r r l S J L f J C L f f C t J I Winter/Spring 1977 AT LONG LAST —An historical view of art made by women by Miriam Schapiro page 4 DIALOGUES WITH NANCY SPERO by Carol De Pasquale page 8 THE SISTER CHAPEL —A traveling homage to heroines by Gloria Feman Orenstein page 12 'Women Artists: 1550— 1950’ ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI — Her life in art, part II by Barbara Cavaliere page 22 THE WOMEN ARTISTS’ MOVEMENT —An Assessment Interviews with June Blum, Mary Ann Gillies, Lucy Lippard, Pat Mainardi, Linda Nochlin, Ce Roser, Miriam Schapiro, Jackie Skiles, Nancy Spero, and Michelle Stuart page 26 THE VIEW FROM SONOMA by Lawrence Alloway page 40 The Sister Chapel GALLERY REVIEWS page 41 REPORTS ‘Realists Choose Realists’ and the Douglass College Library Program page 51 WOMANART MAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P. O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station, New York, N.Y. 10017. Subscription rate: $5.00 for one year. All opinions expressed are those o f the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those o f the editors. This publication is on file with the International Women’s History Archive, Special Collections Library, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60201. Permission to reprint must be secured in writing from the publishers. Copyright © Artemisia Gentileschi- Fame' Womanart Enterprises, 1977. A ll rights reserved. AT LONG LAST AN HISTORICAL VIEW OF ART MADE BY WOMEN by Miriam Schapiro Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Birds and Fruit, ca. -

Download Issue (PDF)

wdmaqart WOMEN SHOOT WOMEN: Films About Women Artists The recent public television series "The Originals: Women in Art" has brought attention to this burgeoning film genre by Carrie Rickey pag e 4 NOTES FROM HOUSTON New York State's artist-delegate to the International Women's Year Convention in Houston, Texas in a personal report on her experiences in politics by Susan S ch w a lb pag e 9 SYLVIA SLEIGH: Portraits of Women in Art Sleigh's recent portrait series acknowledges historical roots as well as the contemporary activism of her subjects by Barbara Cavaliere ......................................................................pag e 12 TENTH STREET REVISITED: Another look at New York’s cooperative galleries of the 1950s WOMEN ARTISTS ON FILM Interviews with women artist/co-op members produce surprising answers to questions about that era by Nancy Ungar page 15 SPECIAL REPORT: W omen’s Caucus for Art/College Art Association 1978 Annual Meetings Com plete coverage of all WCA sessions and activities, plus an exclusive interview with Lee Anne Miller, new WCA president.................................................................................pag e 19 PRIMITIVISM AND WOMEN’S ART Are primitivism and mythology answers to the need for non-male definitions of the feminine? by Lawrence Alloway ......................................................................p a g e 31 SYLVIA SLEIGH GALLERY REVIEWS pa g e 34 REPORTS An Evening with Ten Connecticut Women Artists; WAIT Becomes WCA/Florida Chapter page 42 Cover: Alice Neel, subject of one of the new films about women artists, in her studio. Photo: Gyorgy Beke. WOMANART MAGAZINE Is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215, (212) 499-3357. -

Art&Art History

ART & ART HISTORY Visit us at the annual meeting of the Art Libraries Society of North America, Fort Worth, TX, Mar 19–23 Disaster as Image Classic Greek Masterpieces Iconographies and Media of Sculpture Strategies across Europe by Photini N. Zafiropoulou and Asia This publication presents 60 edited by Monica Juneja magnificent works of ancient Greek and Gerrit Jasper Schenk sculpture. The essays include a This volume collects inter- description and brief commentary disciplinary contributions on each piece. The works, presented to research the depiction, in chronological order, belong to transmission, and inter- the collections of the National Ar- pretation of catastrophes. chaeological Museum in Athens, the Topics discussed range from case studies in historical pictorial Louvre, the Pergamon Museum, the invention during the European Renaissance to the study of British Museum, the Metropolitan contemporary media phenomena, such as the international Museum of Art, and others. coverage of 21st-century catastrophes. 264p, 200 illus (Melissa Publishing 232p, 28 col & 114 b/w illus (Schnell & Steiner, April 2014) House, March 2015) paperback, paperback, 9783795427085, $35.00. Special Offer $28.00 9789602043387, $39.95. Special Offer $32.00 The Hours of Marie de’ Medici A Facsimile introduced by Eberhard König This enchanting illuminated manuscript was painted by one of the renowned Flemish illuminators in the sixteenth century. The volume reproduces all 176 pages of architectural interiors, gorgeous landscapes and detailed city scenes, each one depicting a narrative, as well as floral borders on a gold ground and historiated borders. 352p, 221 col illus (Bodleian Library, March 2015) hardcover, 9781851244072, $250.00. Special Offer $200.00 The Lady with the Phoenix Crown Tang-Period Grave Goods of the Noblewoman Li Chui (711–736) edited by Sonja Filip and Alexandra Hilgner For the first time, this volume presents the reconstruction of the opulent jewelry assemblage of a Tang-period noblewoman. -

Interview with Shirley Gorelick

Interview with Shirley Gorelick Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface This interview is part of the Dorothy Gees Seckler collection of sound recordings relating to art and artists, 1962-1976. The following verbatim transcription was produced in 2015, with funding from Jamie S. Gorelick. Interview DOROTHY SECKLER: This is Dorothy Seckler conducing an interview with Shirley S. Gorelick in Provincetown on August 20, 1968. Shirley, I don't know anything about your early life, where you grew up or what influences in your childhood may have had something to do with your becoming an artist. SHIRLEY GORELICK: I grew up in Brooklyn and I was influenced very early when I as a child in kindergarten painted a picture of Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic and was awarded a prize at Wannamaker which of course gave me an image of myself as an artist. And I think that really was a very important little incident. DOROTHY SECKLER: That's an unusual age at which to have completed a figure and all of that. It was a recognizable figure. SHIRLEY GORELICK: I think I believe I probably copied it. My own image is that I copied it from an illustration on a cigar box. [They laugh.] DOROTHY SECKLER: Well, that would be what most children do. SHIRLEY GORELICK: Yes. DOROTHY SECKLER: Or many do at least at that age. So you achieved fame in kindergarten. SHIRLEY GORELICK: That's right. [They laugh.] SHIRLEY GORELICK: Which I proceeded to lose in a sewer a year or two later. -

Hanne Darboven and the Trace of the Artist's Hand

Mind Circles: on conceptual deliberation −Hanne Darboven and the trace of the artist's hand A JESPERSEN PhD 2015 Mind Circles: on conceptual deliberation −Hanne Darboven and the trace of the artist's hand Andrea Jespersen MA (RCA) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences May 2015 2 Abstract The phrase ‘de-materialisation of the art object’ has frequently assumed the mistaken role of a universal definition for original conceptual art. My art practice has prompted me to reconsider the history of the term de- materialisation to research another type of conceptual art, one that embraces materiality and incorporates cerebral handmade methods, as evidenced in the practice of the German artist Hanne Darboven. This thesis will establish that materiality and the handmade – the subjective – was embraced by certain original conceptual artists. Furthermore, it argues that within art practices that use concepts, the cerebral handmade can function to prolong the artist’s conceptual deliberation and likewise instigate a nonlinear conscious inquisitiveness in the viewer. My practice-based methodologies for this research involved analogue photography, drawing, an artist residency, exhibition making, publishing, artist talks and interdisciplinary collaborations with various practices of knowledge. The thesis reconsiders the definition of conceptual art through an analysis of the original conceptual art practices initiated in New York City during the 1960s and 1970s that utilised handmade methods. I review and reflect upon the status of the cerebral handmade in conceptual art through a close study of the work of Hanne Darboven, whose work since 1968 has been regularly included in conceptual art exhibitions. -

Infinity Mirrors, Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden

Rosemary Macchiavelli DeRosa ∞ www.artregservices.com 1456 Q Street, NW, Washington, DC 20009 ∞T:(202) 332-6702 ∞F:(202) 265-6128 ∞[email protected] Selected Major Exhibitions ~ Art Registration Services 1981 to Present Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden, February - September, 2016 Shirin Neshat: Facing History , Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden, January - July, 2015 Marvelous Objects: Surrealist Sculpture from Paris to New York , Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden, Jan- July, 2015; February - March, 2016 Glittering World: Jewelry of the Yazzie Family , National Museum of the American Indian, May - November, 2014 Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from the Louvre, Versailles, and French National Collections , National Museum of Women in the Arts, February May, 2012; Tour to Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, August, 2012 Nicholai Fechin , tour to Russia, Travel to Kazan, October, 2011; Moscow, August, 2012 Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future , National Building Museum, touring exhibition, 2006-2010 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition I, II, III,IV National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, October, 2005 May, 2006; November, 2008 September, 2009; September, 2012; August - October, 2015 Treasures, National Museum of African Art , Smithsonian Institution, 2004 Saving Mount Vernon: The Birth of the American Preservation , National Building Museum (Full registration services) March, 2002 November, 2003 Palace of Gold & Light: Treasures from the Topkapi, Istanbul , touring exhibition, Palace Arts Foundation (Full registration services) January, 2000 March, 2001 Land of Myth and Fire: Ancient and Medieval Art from the Republic of Georgia , touring exhibition, Foundation for International Arts & Education. (Postponed) 1999 Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance, touring exhibition, The Arts Council of Great Britain & Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1998.