The Geographic Pattern of China's Growth and Convergence Within Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India’S Disputed Borderland Regions: Xinjiang, Tibet, Kashmir and the Indian Northeast

COMPARING CHINA AND INDIA’S DISPUTED BORDERLAND REGIONS: XINJIANG, TIBET, KASHMIR AND THE INDIAN NORTHEAST INTRODUCTION: India and China are seen as the rising giants on the Asiatic mainland today. After the East Asian miracle or miracle of the Asian Tiger economies of the mid-nineties, attention has shifted from the peripheral parts of the Asia Pacific, towards the Asiatic mainland, mainly towards India and China. Both countries have been experiencing impressive economic growth rates since they opened up their economies and exposed their domestic markets to international competition. China opened up its markets in the late seventies, and India opened up its markets in the early nineties. Before the seventies, both economies were by and large protectionist, and had a sluggish economic growth rate. Now, of course, both countries are seen as exciting economic destinations for international investors due to their adventurous markets, which western investors feel the need to tap into and exploit. India, of course, also has the additional prestige of being the world’s largest democracy. However, one area that still remains quite under researched, or at least gets side-lined due to all the talk on economic growth and development is the political situation and the on-going conflicts in the borderland regions of these two emerging powers. Having an understanding of the political situation in the borderland regions is important because if the situation ever blows out of proportion, this could potentially have an adverse impact on the economy, which indirectly impacts on our lives in the west, since western governments have invested so much money in these two countries. -

Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect

Culture, Society, and Praxis Volume 12 Number 1 Justice is Blindfolded Article 3 May 2020 Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect Shiqi Liang University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/csp Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Liang, Shiqi (2020) "Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect," Culture, Society, and Praxis: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/csp/vol12/iss1/3 This Main Theme / Tema Central is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culture, Society, and Praxis by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liang: Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geograph Culture, Society, and Praxis Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect Shiqi Liang Introduction served as the heart of early Chinese In 2016 the city government of Meixian civilization because of its favorable decided to remodel the area where my geographical and climatic conditions that family’s ancestral shrine is located into a supported early development of states and park. To collect my share of the governments. Zhongyuan is very flat with compensation money, I traveled down to few mountains; its soil is rich because of the southern China and visited the ancestral slit carried down by the Yellow River. -

Report on Tibetan Herder Relocation Programs

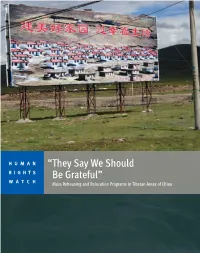

HUMAN “They Say We Should RIGHTS Be Grateful” WATCH Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0336 “They Say We Should Be Grateful” Mass Rehousing and Relocation Programs in Tibetan Areas of China Map: Tibetan Autonomous Areas within the People’s Republic of China ............................... i Glossary ............................................................................................................................ -

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schluessel, Eric T. 2016. The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493602 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 A dissertation presented by Eric Tanner Schluessel to The Committee on History and East Asian Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2016 © 2016 – Eric Schluessel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Mark C. Elliott Eric Tanner Schluessel The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 Abstract This dissertation concerns the ways in which a Chinese civilizing project intervened powerfully in cultural and social change in the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang from the 1870s through the 1930s. I demonstrate that the efforts of officials following an ideology of domination and transformation rooted in the Chinese Classics changed the ways that people associated with each other and defined themselves and how Muslims understood their place in history and in global space. -

The Great Han: the Development, Evolution, and Influence of Chinese Ethnic Nationalism on Modern Chinese Society and Government

The Great Han: The Development, Evolution, and Influence of Chinese Ethnic Nationalism on Modern Chinese Society and Government Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in International and Global Studies Chandler Rosenberger, Xing Hang, Ralph Thaxton, Advisors In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Tinglan Dai May 2016 Copyright by Tinglan Dai Dai 2 Table of Contents I. The Origins of Chinese Civilization and Han Identity II. The Formation of Chinese National Identity in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) III. Chinese National Identity in Republican China (1911-49) IV. National Identity in Maoist China (1949-76) V. National Identity during the Deng Xiaoping Era (1978-1992) VI. National Identity in Contemporary Chinese Society (1992-present) VII. Concluding Thoughts on the Essence of Chinese Civilization and Identity Dai 3 I. The Origins of Chinese Civilization and Han Identity The concept of national consciousness and identity can be characterized as a collective affirmation of a set of common characteristics including a shared history, culture, and ultimately, a common origin that the group takes collective pride in. The foundations of a number of ancient civilizations have been built upon this particular concept. In the case of Chinese civilization, there is the pervasive idea that the inhabitants of the China proper all originated from a single source formed during the beginning of human civilization. This provides a continuous socio- historical narrative for the people of China proper to engage in the formation of a collective identity based on the shared experiences of the group. -

Chinax Course Notes

Part 6: The Manchus and the Qing 23: The Qing Vision of Empire Professor Mark Elliot taught most of this section, allowing us to benefit from his personal focus on the Qing and the Manchus. Professor Bol stepped in for one week to teach The Scholars and Prosperous Suzhou, which must have been his special interest. It was one of the most fascinating weeks of the course129 and by far the toughest. Historical Overview The origins of the Qing dynasty date back to the 1630s with a peasant rebellion led by Li Zicheng, a former postal official. Indeed, this may be the first recorded instance of an individual 'going postal.' 130 Li's rebellion spread through central China, drawing upon the anger of farmers, clerks, and soldiers who were devastated by, among other things, the inflation of copper currency against the silver required for tax payments.131 By the 1640s, the rebel army was moving toward Beijing. Meanwhile, the Manchus, descendents of the Jurchens of the Jin dynasty, were uniting tribal groups northeast of China, forging alliances with the eastern Mongols and raiding the Ming, all under the leadership of Nurhaci. By the late 1620s, the Ming had lost control of the northeast. Hong Taiji, Nurhaci's son and successor, re-organized and strengthened the Jin state, and in the 1630s conquered Korea, bolstering Manchu security and prestige. In 1636, Hong renamed his dynasty the Great Qing (da qing). In 1644, Li's rebels captured Beijing, leading the Ming emperor to hang himself. Shortly after that, the Ming general Wu Sangui, who was guarding the Great Wall at the Shanhai Pass, allied with the Manchus against Li Zicheng, deciding that he preferred the organized armies of the Manchus to the pillaging forces of the rebellion. -

A History of China 1 a History of China

A History of China 1 A History of China The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of China, by Wolfram Eberhard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A History of China Author: Wolfram Eberhard Release Date: February 28, 2004 [EBook #11367] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF CHINA *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Gene Smethers and PG Distributed Proofreaders [Transcriber's Note: The following text contains numerous non-English words containing diacritical marks not contained in the ASCII character set. Characters accented by those marks, and the corresponding text representations are as follows (where x represents the character being accented). All such symbols in this text above the character being accented: breve (u-shaped symbol): [)x] caron (v-shaped symbol): [vx] macron (straight line): [=x] acute (égu) accent: ['x] Additionally, the author has spelled certain words inconsistently. Those have been adjusted to be consistent where possible. Examples of such Chapter I 2 adjustments are as follows: From To Northwestern North-western Southwards Southward Programme Program re-introduced reintroduced practise practice Lotos Lotus Ju-Chên Juchên cooperate co-operate life-time lifetime man-power manpower favor favour etc. In general such changes are made to be consistent with the predominate usage in the text, or if there was not a predominate spelling, to the more modern.] A HISTORY OF CHINA by WOLFRAM EBERHARD CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE EARLIEST TIMES Chapter I : PREHISTORY 1 Sources for the earliest history 2 The Peking Man 3 The Palaeolithic Age 4 The Neolithic Age 5 The eight principal prehistoric cultures 6 The Yang-shao culture 7 The Lung-shan culture 8 The first petty States in Shansi Chapter II 3 Chapter II : THE SHANG DYNASTY (c. -

Late Imperial China

Late Imperial China 1. Mongol Empire 2. Ming Dynasty 3. Trade and Tribute 4. Foundations of the Qing Dynasty 5. Europeans in China Song dynasty 宋 Middle Imperial Period 960 - 1279 ca. 600-1400 Yuan dynasty 元 1279 - 1368 Ming dynasty 明 Late Imperial Period 1368 - 1644 ca. 1400-1900 Qing dynasty 清 1644 - 1911 Republic of China 中華民國 1911-1949 Post-Dynastic Period People's Republic of China 中華人民共和國 1911-present 1949 - present "Northern Zone" Manchuria Xinjiang Mongolia (E. Turkestan) Ordos Tibetan Plateau China Proper Northern Steppe Mongolia Junggar Basin Xinjiang Autonomous Region Kazakhstan steppe Eurasian Steppe Pastoral Nomadism Inner Mongolia Mongol Empire at its height Temüjin Chinggis (Genghis, Jenghis) Khan ca. 1162-1227 Lake Baikal Manchuria Xinjiang Mongolia (E. Turkestan) Ordos Tibetan Plateau China Proper Mongol Empire Mongol script "Han people" hanren 漢人 "southerners" nanren 南人 Khan Emperor tanistry primogeniture Divisions of Mongol Empire mid 13th century Empire of the Great Khan Khubilai Khan 1215-94 Yuan Dynasty 1279 - 1368 Taizu Capitals of the Yuan Dynasty Karakorum Shangdu Dadu (Beijing) Khubilai Khan on horseback Red Turban Rebellion mid. 14th century White Louts Society millenarianism Maitreya cult Population of China, 2 -1500 CE 1. Mongol Empire 2. Ming Dynasty 3. Trade and Tribute 4. Foundations of the Qing Dynasty 5. Europeans in China Zhu Yuanzhang 1328-1398 Ming Dynasty 1368-1644 明 Beijing Nanjing The Hongwu Emperor Ming Taizu r. 1368-1398 Ming Empire Great Wall of China 1. Mongol Empire 2. Ming Dynasty 3. Trade and Tribute 4. Foundations of the Qing Dynasty 5. Europeans in China Yongle Emperor Zhu Di r. -

Imperial China: Practice Makes Perfect?

Chapter 1 Imperial China: Practice Makes Perfect? The Yellow River in Northern China is one of four regions with a legitimate claim to being the ‘cradle of civilisation’—the other three being the Nile in present-day Egypt; the Tigress/Euphrates in present-day Iraq; and the Indus in India/Pakistan1 In each of these regions, evidence dating back beyond four thousand years has been found of people living in settled communities, growing and storing food, specializing in particular skills and exchanging goods and services among themselves. Things moved pretty slowly in those days. In China, just three dynasties presided over the ensuing 1800 years: the Xia for over five centuries (approximately 2000–1450 BC); the Shang, for three centuries (1450–1122 BC); and the Zhou for nine centuries (1122–221 BC)—still the record). The later emperors of the Zhou presided over ethnic Chinese (or Han) communities that had expanded well north of the Yellow River and to south of the Yangzi River in central China, as well as eastward to the coast and westward along and between these two great rivers. From around 500 BC, Zhou authority began to erode and conflict within the broader Chinese community escalated. Over time, the warring groups coalesced into seven larger polities that considered themselves separate entities that had their own army, collected their own taxes, concluded treaties and so forth. Chinese expansion to the north and west led to contact with the nomadic tribes of these regions, known today as Manchuria and Mongolia. The determining commodity was the horse which the nomads traded for the grain, cloth, tools and utensils produced by the settled Chinese. -

Whose Xinjiang?The Transition in Chinese Intellectuals'imagination Of

2011 WHOSE XINJIANG? THE TRANSITION IN HARVARD-YENCHING CHINESE INTELLECTUALS’ IMAGINATION INSTITUTE WORKING OF THE “NEW DOMINION” DURING THE PAPER SERIES QING DYNASTY Jia Jianfei | Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Whose Xinjiang? The Transition in Chinese intellectuals’ imagination of the “New Dominion” during the Qing dynasty Jia Jianfei Abstract: Though Xinjiang (literarily the ―New Dominion‖) was incorporated into China’s territory permanently in the mid-18th century during Emperor Qianlong’s reign, Jiayu Guan (嘉 峪关) still marked a boundary between Xinjiang and China proper, much like Yang Guan (阳关) and Yumen Guan (玉门关) in the Han and Tang dynasties. Such a boundary was infused with cultural meaning since ancient times: it separated different cultures, and territories beyond the pass were accordingly not be regarded as part of China. This understanding of cultural boundaries deeply influenced Han Chinese officials and intellectuals; no wonder few Han Chinese supported the Qing emperors’ military plans in Xinjiang during the conquest. Even after the Qing conquest of Xinjiang, such conceptions remained relevant and fueled controversy over Xinjiang, lasting to the end of Qing dynasty and even into the Republic. However, these ideas gradually weakened over time, resulting in the re-conquest of Xinjiang during the 1860s and 1870s by Zuo Zongtang (左宗棠), a Han Chinese, the establishment of Xinjiang province in 1884, and the swift development of Xinjiang-studies during the Guangxu reign period (1875-1908). Indeed, the place of Xinjiang in Han Chinese intellectuals’ imagination had changed significantly, and this change played a key role in the crystallization of modern China’s boundaries. -

China's Cadre Transfer Policy Toward Tibet in the 1980S

China’s Cadre Transfer Policy toward Tibet in the 1980s YASHENG HUANG University of Michigan There is a crucial distinction between population migration and personnel transfer. The latter is a systematic and deliberate govern- ment program to move people from one location to another. Such a movement can be induced by the financial or non-financial incentives the government sets up specifically to accomplish such an objective and/or it can be directly organized by the government via administra- tive methods. China’s transfer policy toward Tibet is implemented on the basis of both incentives and administrative compulsion. Migration, on the other hand, refers to a spontaneous movement of people from one place to another. There are complex causes for such a movement, including economic opportunities and family-related considerations. Even though Chinese migration to Tibet has caused great resentment in Tibet, it should be recognized that such a movement of people has been a result of a nationwide relaxation of economic control rather than a result of a deliberate government program specifically aimed at Tibet.’ As such, migration is a lesser indication of government intentions toward Tibet than is personnel transfer policy specifically designed for Tibet. This article focuses on the personnel transfer policy of the Chinese government in the 1980s and on the politically and strategically sensitive personnel (i.e., cadres) transferred to Tibet. First, the reason for this focus has to do with the fact that the Chinese transfer policy AUTHOR’S NOTE: I wish to thank Jmg Jun for a stimulating conversation on the subject and for sharing his own research and sources. -

Cultural Influences on Toy Design

Cultural Influences on Toy Design A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Design in the School of Design College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning By Hui Wang Bachelor of Technology, Beijing Forestry University June 20, 2012 Committee Chair: Gerald Michaud Committee Member: Margie Voelker-Ferrier and Mikiko Hirayama Abstract Traditional cultures are human treasures. It is necessary to preserve traditional cultures. Due to political, economic, cultural influences, and globalization, the loss of traditional culture becomes a severe problem and needs to be addressed. Education is an important means of spreading culture. For children, toys can be great educational tools as well as entertaining playthings. Through playing with appropriate educational toys, children learn a lot while having fun. Therefore, it is possible for children to learn traditional culture by playing with toys. This thesis focuses on finding how cultural influences can be integrated into toys. By integrating Han ethnic clothing with dolls as an example, I discuss the impact it can bring to children’s traditional cultural education and propose guidelines for cultural educational toy design. 2 3 Acknowledgement “Thank you” is not enough to express my appreciation to my thesis committee members. But still, I would like to first thank Professor Gerald Michauld for his kindly two years’ company of advising me during my entire master of design program. Thank him for always wanting me to accomplish what I want to pursue as a designer, and thank him for enlightening me and pulling me back to the right track at every stage of the thesis.