Inquiry Into the Franchising Bill 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Chains Have Big Growth Plans Under Way in WA

Franchises • Major chains have big growth plans under way in WA • Franchises positive about economy, leasing market • Tough employment laws a potential problem • Businesses turn to technology and value adding to distinguish products Bullish franchises plan to expand Whether it’s burritos, car repairs or mortgage advice, a number of big franchises are targeting growth in 2018. ATRONS dining-in Mr Pickard said the they spoke to Business would be reopened within with a cold beer Watertown restaurant News. a month. Pwill be a key part aimed to put a modern Zambrero, wh ich Melbourne-based of the expansion strat- twist on the offering, entered the state in 2013, Bakers Delight joint-chief Matt Mckenzie egy for Bucking Bull in encouraging an increase already has 32 stores in executive, David Christie, [email protected] @Matt_Mckenzie_ Western Australia, as in the average spend per WA, with about eight said his company had the traditionally food person of about 50 per more in the pipeline for opened six new shops in court-focused business cent, to $18 a head, com- this year. Perth’s southern region moves into higher value pared with the traditional Zambrero general during the past 18 months. markets, according to food court. manager WA Steve Wad- Mr Christie said prod- Franchise Fusion manag- The availability of dingham said the local uct innovation was a ing director Troy Pickard. alcohol with a meal also market had been one major part of the strategy Bucking Bull is owned changed the dynamic, he of the strongest for the for the bakery to grow by Queensland-based said. -

Health &Beauty

SPRING / SUMMER 2014 YOUR CHANCE TO WIN* A $1000 SCULPT STUDIO GIFT VOUCHER JUNGLE HEALTH FEVER & BEAUTY SEASON TRENDS SPRING INTO SUMMER SPRING/SUMMER Lakeside Joondalup would like to present our spring / summer 2014 magazine. This issue showcases the latest international trends to keep you looking fabulous this season. We would like to thank Wanneroo Botanical Golf Gardens and Leap Frogs Sandals and sunnies are essential every spring / summer in Perth. Team them with a bold patterned jumpsuit or shorts to Café for their wonderful hospitality and assistance during the photoshoot for this issue. achieve that perfect seasonal look, all available at Lakeside Joondalup. 3 Spring / Summer Women’s Trends ZIRCONIA 4 Jungle Fever - Women’s Fashion EARRINGS TURQUOISE 9 The Ultimate Day at the Races - SHIELS $49.95 SANDALS Women’s Trends NOVO $49.95 10 Sizzling Men’s Trends ECC CHARM 11 Botanic Shades - Street Fashion WATCH 14 Secret Garden - Kid’s Fashion SHELLY SHIELS $99.00 SCORELLI 16 Health & Beauty TROPICANA SICILLY 17 Centre Directory SANDALS 18 Update: Redevelopment 11 SANDALS WILLIAMS $69.99 NOVO $49.95 WIN A $1,000 SCULPT WIZARD TAN STUDIO GIFT VOUCHER! SANDALS THE ULTIMATE BETTS FOR HER $59.99 DAY AT H2OH! THE RACES BLUE This spring / summer at Lakeside Joondalup you BATHERS CARIS WEARS BRAS N THINGS will find the latest trends to TRANSIT TOP $59.95, TRANSIT SHORTS $69.95, $74.99 help you look fabulous on KATIES PURPLE NECKLACE $19.95 & KMART 16 race day. 9 BRACELETS $7.00. Legal: Every reasonable effort to ensure the accuracy of this magazine has LAKESIDE JOONDALUP TEAM been taken by Lend Lease Property Management (Australia) Pty Limited Marketing Manager Kimberley McCone OROTON ABN 61 002 894 153 (Lend Lease) and its agents. -

Win $1,500 Go Wild with a Worth of LUXE Shoes from Zu TOUCH

WIN $1,500 Go wild with a worth of LUXE shoes from Zu TOUCH It’s a Winter FORWonderland KIDS FASHION WINTER trends & must haves for this season ASHION Winter F HAIR& BEAUTY TIPS 6 REDEVELOPMENT CONTENTS UPDATE Lakesideondalup would Jo like to present our winter 2014 magazine. yleThe team st has put together a snapshot of our favourite fashion ructionConst work on the new Lakeside Joondalup Shopping City is omfinds across fr the huge range of stores, giving you the perfect ogressingpr well as we transform the centre to become the largest inspir re in WA upon completion, due to open late 2014. ation for your winter wardrobe. shopping cent 16 Redevelopment Update Once opened Lakeside Joondalup Shopping City will 2 offer customers a new two-level, 12,000 square metre 4 Season Picks - Women’s Trends Myer department store, a new casual dining precinct and approximately 95 national and local retailers. 6 Luxe Touch - Women’s Fashion With the new look South Mall and multi-deck car park Hair & Beauty Tips now open; works are now progressing on the Coles 11 refurbishment which is set for completion in late August 12 Men’s Must Haves - Men’s Trends LAKESIDE 2014. On completion, Coles Joondalup will become JOONDALUP TEAM the first of their ‘Next Generation’ stores in Western 13 Talk of the Town - Street Fashion Marketing Manager Australia, focussed on creating an outstanding customer Kimberley McCone experience. While construction work is underway, 16 Winter Wonderland - Kid’s Fashion Marketing Executive Coles Joondalup will remain open for business as usual. -

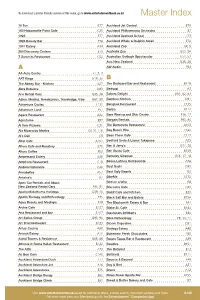

Master Index

To download a printer friendly version of this index, go to www.entertainmentbook.co.nz Master Index 16 Tun B77 Auckland Jet Central E79 160 Hobsonville Point Cafe C25 Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra E7 1925 F77 Auckland Seafood School F23 1925 Beauty Bar F76 Auckland Whale & Dolphin Safari E74 1947 Eatery A39 Auckland Zoo E4, 5 360 Discovery Cruises E78 Australia Zoo G53, 54 7 Summits Restaurant C52 Australian Outback Spectacular G51, 52 Avis New Zealand G25, 26 A AW Audio F92 AA Auto Centre F1, 2, 3 AAT Kings G19, 20 B The Abbey Bar - Kitchen A47 The Backyard Bar and Restaurant B119 Abra Kebabra D83 Baduzzi A3 Ace Rental Cars G35, 36 Bakers Delight D61, 62, 63 Adina, Medina, Rendezvous, Travelodge, Vibe G67, 68 Bamboo Kitchen D91 Adventure Cycles E131 Bangkok Restaurant C135 Adventure Land E57 Barb’s B114 Agave Restaurant A42 Bare Waxing and Skin Centre F16, 17 Agrodome E97 Bargain Rentals F93, 94 Al Volo Pizzeria C21 The Barracuda Restaurant A103 Ala Moana by Mantra G115, 116 Bay Beach Hire E160 Al’s Deli C8 Bean There Cafe C117 Altar Cafe A104 Bedford Soda & Liquor Takapuna A35 Altura Cafe and Roastery B75 Ben & Jerry’s D37, 38 Altura Coffee F53 Ben Gusto Cafe B125 Ampersand Eatery A36 Berkeley Cinemas E16, 17, 18 Amphora Restaurant C18 Besos Latinos Restaurante A76 Andrea Ristorante C40 Best Sushi D90 Annabelles A54 Best Ugly Bagels B3 Antoine’s A2 BikeMe E130 Apex Car Rentals and About Bird on a Wire B8 New Zealand Rental Cars F90, 91 Biscocho Cafe C80 Apollo Motorhome Holidays G39, 40 Biskit Cafe and Kitchen B20 Apollo Therapy and Re exology F35 Black Salt Bar and Eatery B154 Aqua Beauty and Medispa F39 The Blacksmith Eatery & Bar B44 Archie Cafe B137 Blake St. -

Popular and Casual Dining Informal Dining And

POPULAR AND CASUAL INFORMAL DINING AND FAMILY FUN ACTIVITIES RETAIL AND LEISURE DINING TAKEAWAY AND ATTRACTIONS • Siena’s Pizzeria and Ristorante • McDonald’s • Grand Cinemas • Cash & Carry Caffe • Hungry Jack’s • Ace Cinemas • Dreamworld • Arirang Korean BBQ Restaurant • Fit Chips • Hoyts Cinemas • Sea World • Villa Picasso Ristorante • One for the Road • West Australian Ballet • Warner Bros. Movie World • Han Palace • Eagle Boys Dial-A-Pizza • Western Australian Maritime • Coles • Sicilian Café • Brumby’s Museum • JT’s Ladies’ and Men’s • Bar 138 on Barrack • Java Juice • Captain Cook Cruises Hairstylists • Mez Mediterranean Cuisine • Pastarazzi • AMF Bowling Centres • Vogue Magazines • Metro Bar and Bistro • Hudsons Coffee • Wanneroo Botanical Gardens • Hamilton Island • Valley View Restaurant • Muzz Buzz • Adventure World • Wet’n’Wild Water World • Avis Australia • Gavino Restaurant • The Fudge Factory Margaret • The Great Escape • Monte Fiore Café Restaurant River • Timezone • Liquor Merchants WA • Star Surf Shop • Globe Coffee House Patisserie • The Coffee Club • The Beach House Kids Fun • Australian Gourmet Traveller • Citro Bar and Restaurant • Avanti Café & Pizzeria Centre Magazines • Brando’s Pizzeria Café • NYC Pizza • Cockburn Ice Arena • Pixi Foto and Portrait Place • Atrium Garden Restaurant • Margaret River Chocolate • Scitech • Party Plus • Alaturka Cuisine Company • Indoor Kart Hire O’Connor • Blown Away! • Oriel Cafe Bar and Brasserie • Gelatino • Australian Pinnacle Tours • Civic Video • McCafé • Deckchair Theatre Company • Severino Garden Restaurant • Friendlies Chemists • The Wild Fig Café • Cookie Man • Kookaburra Cinema and many more... • Fratelli Restaurant • Donut King • Fremantle Prison • Buddha Bar Curry House • Wokinabox • Q-Zar • Jimmy Dean’s Diner • Chelsea Pizza Company and many more... and many more... • Pasticceria Fiorentina • Madzoon and many more.. -

Participating Shopping Centre Participating Retailer Altona Gate

Participating Shopping Centre Participating Retailer Altona Gate 21st Century Bakery Altona Gate Aldi Altona Gate Asian Express Altona Gate Australia Post Altona Gate Bakers Delight Altona Gate Barber Dollz Altona Gate Beauty 4 Life Altona Gate Best & Less Altona Gate Biblos Altona Gate Bonds Altona Gate Bras N Things Altona Gate Chemist Warehouse Altona Gate Cobbler Plus Altona Gate Coles Altona Gate Connect Hearing Altona Gate Cuts Only Altona Gate EB Games Altona Gate Empire Street & Surf Wear Altona Gate Exquisite Brows & Spa Altona Gate Ferguson Plarre Bakehouses Altona Gate G-Bags Altona Gate Hangar Cafe Altona Gate House And Party Altona Gate Jacqui E Altona Gate Jewellery International Altona Gate Just Jeans Altona Gate Kmart Altona Gate King Carvery Altona Gate Knot And Crop Altona Gate La Sheesh Kebab & Grill Altona Gate Lindens Fresh Meats Altona Gate Lux Hair Altona Gate Michel's Patisserie Altona Gate Nails 1st Altona Gate Noodle Box Altona Gate OPSM Altona Gate Optus Altona Gate Phone Solution Altona Gate Priceline Altona Gate Romanos Coffee Altona Gate Rox Chinese Massage & Acupuncture Altona Gate Saccas Fine Foods Altona Gate Salera's Jewellers Altona Gate Sandwich Chefs Altona Gate Sheridan Outlet Altona Gate Shop N Shine Altona Gate Soul Mobile Altona Gate Specsavers Altona Gate Spendless Shoes Altona Gate Sportsco Altona Gate Subway Altona Gate Sushi Sushi Altona Gate Sussan Altona Gate Suzanne Grae Altona Gate Takechiho Altona Gate Telstra Store Altona Gate The Reject Shop Altona Gate Vans Clothing Alterations Altona -

THE CONSERVATORIUM a Duet of Dutch Architecture and Italian Design for Amsterdam’S Latest Luxury Hotel COVER STORY

THE ALI GROUP MAGAZINE ISSUE 2 | OCTOBER 2013 THE CONSERVATORIUM A duet of Dutch architecture and Italian design for Amsterdam’s latest luxury hotel COVER STORY HOT NEWS ABOUT ICE Scotsman Industries joins Ali Group CHINA: THE BIG CHALLENGE How to take advantage of new opportunities with Ali as your partner CARPIGIANI GELATO UNIVERSITY Success stories from around the world McCAFÉ McDonald’s new café concept baked by Moffat INDEX THE ALI GROUP MAGAZINE Issue 2 | October 2013 PROFILE 2 Heir apparent: Filippo Berti prepares to lead Ali Group through its next decades of success Hello everyone! I am happy to share with you the new issue of AliWorld, COVER STORY the Ali Group magazine dedicated to the hospitality and foodservice industry. 4 The Conservatorium’s big encore A big thank you goes out to my colleagues around the world who once again helped me discover the most interesting PEOPLE stories. Their tales take us into the heart of extraordinary projects that our companies develop in various areas of foodservice. 10 Just add ice: Ali Group joins forces with premier ice-machine company Scotsman I hope the articles in this issue will transmit all the passion Focus on: Scotsman Industries and enthusiasm that inspired each project. I invite you write to me with new ideas for interviews and 14 Kitchens and laundry facilities without product news for future issues. Please feel free to send your boundaries comments to: [email protected]. Any suggestions that will make AliWorld richer and more interesting are welcome! Focus on: Alicontract It will be a great pleasure to hear from you and give space to your suggestions. -

FCA Senate Inquiry Submission April 2017 Contents

FCA Senate Inquiry Submission April 2017 Contents About Us 4 01 Submission Synopsis 6 02 Specific Recommendations For Legislative Amendment 7 03 Franchise Sector Overview 8 04 Employee Underpayment 15 05 Legislation 22 06 Regulatory Impact And Compliance Costs 34 07 Transition 37 08 Conclusion 38 Appendices A1 Current FCA Members A2 FranData Survey A3 WFC Declaration Stephen Palethorpe Secretary Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment P O Box 6100 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Committee Secretariat, INQUIRY – Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Bill 2017 Thank you for your 24 March 2017 letter inviting the Franchise Council of Australia (FCA) to make a submission to the concurrent inquiry into three (3) Fair Work Act Amendment Bills. The FCA makes this submission specifically in relation to the Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Bill 2017 as this is the most relevant and prescient for the franchise community. Our detailed submission is attached. It outlines the current state of franchising in Australia, an assessment of the public policy merits of the proposed legislation, addresses key areas of concern with the Bill as currently drafted and makes a number of specific recommendations for the Committee’s consideration. In support of the FCA’s submission and recommendations, our Association welcomes the Committee’s invitation to appear before it at your Canberra Hearing on Wednesday, April 12, 2017. At this hearing, we can provide further information in support of our submission, address any particular questions that the Committee may have and provide suggested steps to give effect to the FCA’s recommendations if this is of interest to the Committee. -

Attachment a to Trade Promotion Guidelines

SCA – PROMOTION TERMS & CONDITIONS SCHEDULE TO CONDITIONS OF ENTRY Project Number 22217 Promotion mix94.5 Live it Up at Lakeside Joondalup Promoter Name The promoter is (jointly and severally where applicable) Perth FM Radio Pty Ltd (ABN 22 077 569 110) trading as: MIX 94.5 of 450 Roberts Road, Subiaco WA 6008 and 92.9 FM of 450 Roberts Road, Subiaco WA 6008. (the “Promoter”) Website www.mix.com.au Promotional Period Opens 20 April 2015 Closes 3 May 2015 The Promoter may amend the Promotional Period in accordance with state legislative rules. Registration Period Opens 20 April 2015 at 9:00am Closes 3 May 2015 at 11:59pm The Information Kiosk will be open from 9.00am – 5.30pm Monday – Wednesday and Fridays, 9.00am –9.00pm Thursdays, 9.00am – 5.00pm on Saturdays and 11.00am – 5.00pm on Sundays for the duration of the Promotional Period. Entry Restrictions Entrants must be at least 18 years or older. Entry is not open to persons who qualify as employees of Lend Lease (Australia) Pty Ltd and Retailers within Lakeside Joondalup Shopping City and their immediate families. Relevant State Entries are restricted to residents of Western Australia. Maximum Entries Multiple entries are permitted, however only one (1) entry will be valid per unique code. An entrant is only eligible to redeem one (1) Prize in the Promotion. Entry Procedure To enter, entrants must, during the Promotion Period: 1. Make a purchase of $20.00 or more in one transaction at a permitted Lakeside Joondalup Shopping City retailer during the Promotional Period; 2. -

Master Index

To download a printer friendly version of this index, go to www.entertainmentbook.com.au Master Index 63 Degrees B1 Ballarat Bird World E23 7 Origins B22 Ballarat Ghost Tours E30 9 grams A53 Ballarat Indoor Go-Karts E14 Ballarat Old Cemetery Night Tours E31 A AAT Kings H19, 20 Ballarat Salt Rooms & Wellness Centre G18 ACE H61, 62 Ballarat Steakhouse A29 Adairs F11, 12 Ballarat Tokyo Grill House A75 Adina & Medina Apartment Hotels J29, 30 Ballarat Wholefoods Cafe B48 Air New Zealand H7, 8 Ballarat Wildlife Park E22 Airodrome Trampoline Park E49, G27 Ballarat’s Sanctuary Day Spa G4 Ala Moana by Mantra J77, 78 Ballarista B33 All 4 Kids Indoor Play Centre Geelong E65 Bannockburn Railway Hotel C16 Apollo Motorhome Holidays H65, 66 Bare Skin and Body Clinic G6 Aradale Tours E32 Barrabool Hills Beauty G14 Arajilla J15, 16 Barwon Club Hotel A73 Art Series Hotel Group J39, 40 Barwon Heads Hotel B2 Arthurs Seat Eagle E63 Barwon Hotel Winchelsea C28 Asahi Japanese Restaurant A16 Basils Farm A27 Astral Tower J11, 12 Baskin-Robbins D48 Athletic Club Brewery G31 Bay View Bar & Grill B40 Australia Zoo H29, 30 BCF F19, 20 Australian National Sur ng Museum E41 Beachside Blooms Florist G25 Australian Outback Spectacular H27, 28 Bear and Bean B9 Australian Skydive E42 Bearded Bros HQ B20 Avanti at Witchmount Estate A22 Bellarine Estate G28 Avis Australia H49-52 Bellarine Railway E29 Bellbrae Estate B17 B Baie Wines G30 Belle’s Skin and Beauty G19 Bake Boss G43 Belmont Hotel A58 Bakers Delight D13, 14, 15 Black Bull Tapas Bar and Restaurant A39 Visit www.entertainmentbook.com.au for additional offers, suburb search, important updates and more. -

Download Original Attachment

Trading Name Ward Rhthym Cafe Waitemata BEAGLE CAFE Waitemata Mint Kitchen Catering Limited Waitemata Gourmet A-Gogo Waitemata Big Boy Takeaway Albert - Eden Bandito Cantina Orakei Thai Noodles Mangere - Otahuhu Traditional Thai Sizzlers Mangere - Otahuhu 46 & York Limited Waitemata The Java Room Waitemata Newton Road Takeaway Waitemata Wok Express Waitemata Station Road Lunchbar Mangere - Otahuhu Baduzzi Waitemata Wilder And Hunt Waitemata Better Butchers of Mt Eden Ltd Albert - Eden Cafe Greenfingers Orakei New Century Cafe Waitemata Calimero Orakei Pinchos Orakei PHO Saigon Restaurant Waitemata Live Fish Restaurant & Bar Waitemata Kyoto Albert - Eden Shahi - Indian Experience Restaurant And Takeaway Waitemata Benson Road Deli Orakei Black Sugar Grill Orakei Han's Sushi Limited Waitemata Shahi - Indian Experience Restaurant And Takeaway Waitemata Shahi - Indian Experience Restaurant And Takeaway Orakei Shooters Saloon Albert - Eden Divine Foods Ltd Albert - Eden Fork Maungakiekie - Tamaki Chilando Mexican Tequera Albert - Eden The Healthy Salt Company Whau Tony's Wellesley Street Waitemata Tom Yum Goong Thai Restaurant & Takeaway Orakei Sal's Ny Pizza Wynyard Quarter Waitemata Pizza Hut Mt Albert 810 Albert - Eden The Coffee Club St Lukes Albert - Eden Baker's Diary Whau Volt 2 Go Waitemata Safira's Treats Puketapapa Long Rainbow Takeaway Maungakiekie - Tamaki Shogun Sushi Orakei Angel Thai Restaurant Orakei Eden Park Catering Albert - Eden The Gingerbread House - Glendowie Orakei Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers Maungakiekie - Tamaki -

Reassessing Food Insecurity in Melbourne's Outer East

Edited by: Sheridan Clugston, Accredited Practicing Dietitian Deborah Cocks, Outer East Primary Care Partnership © 2013 Written by: Sheridan Clugston, Elisa Rossimel Monash University, 2011 With support from: Michelle Fleming, Yarra Valley Community Health Claire Palermo, Monash University Contact: Deborah Cocks – [email protected] PAGE 2 Reassessing Food Insecurity in Melbourne’s Outer East Contents Executive Summary 5 1. Background 7 1.1 Food Insecurity 8 1.2 Food Insecurity in the Outer East 8 1.3 Trends in Australian Household Expenditures 9 1.4 The Cost of Healthy Eating – Fruit, Vegetables and Food Insecurity 11 1.5 Community Interventions to Food Insecurity 12 1.6 Smoking and Alcohol Linked with Food Insecurity 14 1.7 Food Security, the Agri-food System and the Outer East 15 1.8 The Importance of Strong Local Data 17 2. Methodology 19 2.1 Victorian Healthy Food Basket Survey 20 2.2 Modifi ed Victorian Healthy Food Basket Survey for Green Grocers 20 2.3 Mapping - Listing Food Retailers and Community Interventions Targeting Food Insecurity. 20 2.4 Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas 21 2.5 Statistical analysis 21 3. Results 23 3.1 Victorian Healthy Food Basket Survey 24 3.2 Fruit and Vegetables 29 3.3 Community Interventions Targeting Food Insecurity 30 3.4 Changes in the Number of Food Premises 34 3.5 Tobacco and Alcohol 36 4. Discussion 37 4.1 Victorian Healthy Food Basket Survey 38 4.2 Fruit and Vegetables 38 4.3 Community interventions 39 4.4 Changes in the Number of Food Premises 40 4.5 Changes in the Cost of Food Groups 41 4.6 Tobacco & Alcohol 41 4.7 Strengths of the Methodology 41 4.8 Weaknesses of the Methodology 42 Reassessing Food Insecurity in Melbourne’s Outer East PAGE 3 Contents [continued] 5.