The True Odor of the Odorous House Ant CLINT A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ants and Their Relation to Aphids Charles Richardson Jones Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1927 Ants and their relation to aphids Charles Richardson Jones Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Charles Richardson, "Ants and their relation to aphids" (1927). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14778. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14778 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Buczkowski G. and Krushelnycky P. 2011. the Odorous House Ant

Myrmecological News 16 61-66 Online Earlier, for print 2012 The odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), as a new temperate-origin invader Grzegorz BUCZKOWSKI & Paul KRUSHELNYCKY Abstract A population of the odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile, was found at an upland site on Maui, Hawaii. Although T. sessile possesses many of the traits shared by most invasive ant species and is a significant urban pest in the continental USA, this represents the first confirmed record for this species outside its native North American range. Our survey of the site revealed a relatively large (ca. 17 ha) infestation with many closely spaced nests, possibly all belonging to a single supercolony as suggested by the lack of aggression or only occasional non-injurious aggression between workers from distant nests. The odorous house ant is currently abundant at this site, despite the presence of seven other intro- duced ant species, including the big-headed ant (Pheidole megacephala) and the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). Based on its behavior at this site, T. sessile may successfully invade other temperate areas in the future, and should be watched for by biosecurity programs. Key words: Invasive ants, odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile, Hawaii. Myrmecol. News 16: 61-66 (online xxx 2010) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 26 April 2011; revision received 13 July 2011; accepted 28 July 2011 Subject Editor: Philip J. Lester Grzegorz Buczkowski (contact author), Department of Entomology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Paul Krushelnycky, Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Food Preference, Survivorship, and Intraspecific Interactions of Velvety Tree Ants Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75r0k078 Author Hoey-Chamberlain, Rochelle Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Food Preference, Survivorship, and Intraspecific Interactions of Velvety Tree Ants A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology by Rochelle Viola Hoey-Chamberlain December 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Michael K. Rust, Chairperson Dr. Ring Cardé Dr. Gregory P. Walker Copyright by Rochelle Viola Hoey-Chamberlain 2012 The Thesis of Rochelle Viola Hoey-Chamberlain is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In part this research was supported by the Carl Strom Western Exterminator Scholarship. Thank you to Jeremy Brown for his assistance in all projects including collecting ant colonies, setting up food preference trials, setting up and collecting data during nestmate recognition studies and supporting other aspects of the field work. Thank you also to Dr. Les Greenburg (UC Riverside) for guidance and support with many aspects of these projects including statistics and project ideas. Thank you to Dr. Greg Walker (UC Riverside) and Dr. Laurel Hansen (Spokane Community College) for their careful review of the manuscript. Thank you to Dr. Subir Ghosh for assistance with statistics for the survival study. And thank you to Dr. Paul Rugman-Jones for his assistance with the genetic analyses. iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Food Preference, Survivorship, and Intraspecific Interactions of Velvety Tree Ants by Rochelle Viola Hoey-Chamberlain Master of Science, Graduate Program in Entomology University of California, Riverside, December 2012 Dr. -

Abstract POWELL, BRADFORD EDMUND

Abstract POWELL, BRADFORD EDMUND. Interactions between the ants Linepithema humile, Tapinoma sessile and aphid mutualists. (Under the direction of Jules Silverman.) Invasive species have major impacts on the ecosystems they invade. Among the most disruptive groups of invasive species are ants. Invasive ants have caused losses in biodiversity among a wide range of taxa, including birds, mammals, lizards, but especially towards ground nesting arthropods such as native ants. Why native ants are so susceptible to invasion and how invasive ants are able to sustain massive population growth remain unclear. It has been suggested that invasive ants utilize carbohydrate resources from hemipteran exudates to fuel aggressive foraging and colony expansion. Perhaps invasive ants are simply more proficient at usurping these resources, maintaining higher hemipteran populations, etc.? I use a model invasive, the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) and a native ant (Tapinoma sessile) to compare hemipteran tending ability and ant competition. Through a series of laboratory and field experiments I evaluated 1) sucrose consumption by individual and groups of ant workers, 2) the effect either ant species had on hemipteran population growth rates in a predator-free space, 3) the defensive ability of either ant against hemipteran predators and parasitoids, and 4) the proportion of invasive ants required to displace a native colony from a hemipteran resource. Whereas there was no difference between the species in their ability to sequester liquid resources, recruitment strategies differed considerably. Hemipteran populations in the presence of L. humile grew larger in a predator free environment and populations exposed to predators were better defended by L. humile than T. -

Recent Human History Governs Global Ant Invasion Dynamics

ARTICLES PUBLISHED: 22 JUNE 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 0184 Recent human history governs global ant invasion dynamics Cleo Bertelsmeier1*, Sébastien Ollier2, Andrew Liebhold3 and Laurent Keller1* Human trade and travel are breaking down biogeographic barriers, resulting in shifts in the geographical distribution of organ- isms, yet it remains largely unknown whether different alien species generally follow similar spatiotemporal colonization patterns and how such patterns are driven by trends in global trade. Here, we analyse the global distribution of 241 alien ant species and show that these species comprise four distinct groups that inherently differ in their worldwide distribution from that of native species. The global spread of these four distinct species groups has been greatly, but differentially, influenced by major events in recent human history, in particular historical waves of globalization (approximately 1850–1914 and 1960 to present), world wars and global recessions. Species in these four groups also differ in six important morphological and life- history traits and their degree of invasiveness. Combining spatiotemporal distribution data with life-history trait information provides valuable insight into the processes driving biological invasions and facilitates identification of species most likely to become invasive in the future. hallmark of the Anthropocene is range expansion by alien been introduced outside their native range). For each species, we species around the world1, facilitated by the construction of recorded the number of countries where it had established (spatial transport networks and the globalization of trade and labour richness) and estimated spatial diversity taking into account pair- A 2 16 markets since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution . -

Effect of Ant Attendance on Aphid Population Growth and Above Ground Biomass of the Aphid’S Host Plant

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 114: 106–112, 2017 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2017.015 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of ant attendance on aphid population growth and above ground biomass of the aphid’s host plant AFSANE HOSSEINI 1, MOJTABA HOSSEINI 1, *, NOBORU KATAYAMA 2 and MOHSEN MEHRPARVAR 3 1 Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran; e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Kyoto University, Kyoto Center for Ecological Research, Japan; e-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Biodiversity, Institute of Science and High Technology and Environmental Sciences, Graduate University of Advanced Technology, 7631133131 Kerman, Iran; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Hemiptera, Aphididae, Hymenoptera, Formicidae, ant-aphid interaction, aphid performance, population growth, developmental stage, plant yield Abstract. Ant-aphid mutualism is considered to be a benefi cial association for the individuals concerned. The population and fi tness of aphids affected by ant attendance and the outcome of this relationship affects the host plant of the aphid. The main hypothesis of the current study is that ant tending decreases aphid developmental time and/or increases reproduction per capita, which seriously reduces host plant fi tness. The effect of attendance by the ant Tapinoma erraticum (Latreille, 1798) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on population growth and duration of different developmental stages of Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae) were determined along with the consequences for the fi tness of the host plant of the aphid, Vicia faba L., in greenhouse conditions. -

Eb1550 ODOROUS HOUSE

EB1550 ODOROUS HOUSE ANT Tapinoma sessile (Say), the odorous house ant, is a widely distributed native species found throughout the United States, in Canada, and Mexico. The common name of this insect is derived from a peculiar coconutlike odor produced in the anal glands. A large population of these ants live in western Washington, between Vancouver, British Columbia and Portland, Oregon. Odorous house ants are less common in the semidesert areas of the Pacific Northwest. Identification All odorous house ant workers are the same size (monomorphic). They differ from other ant species by the presence of a slitlike cloacal orifice without fringe hairs (Fig. 1). Antennae are 12 segmented and without a club (enlargement) at the tip. The promesonotal and mesoepinotal sutures are both distinct; the latter is even more distinct (Fig. 2). The single-segmented petiole (connection between thorax and abdomen) has no node (Fig. 2), a factor that distinguishes it from the ant in Fig. 3. 1 Workers are approximately /16 inch long and have a uniform brown to black color. Fig. 1. Transverse ventral orifice (A, lateral view; B, ventral view). Fig. 2. Tapinoma sessile (odorous house ant).* Fig. 3. Lasius spp. (Cornfield and other ants).* *Figs. 2 and 3 have been modified from USDA Tech. Bull 1326. Biology Odorous house ants have adapted to a wide range of habitats and thrive nearly everywhere from sea level to about 10,500 feet. They nest in sand, pastures, grass fields, forests, bogs, and houses. They frequently nest under stones and logs. They also build nests under stumps and under the bark of dead trees, in bird and mammal nests, in plant galls, and in debris. -

Ghost Ant, Tapinoma Melanocephalum (Fabricius) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae)1 J

EENY310 Ghost Ant, Tapinoma melanocephalum (Fabricius) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae)1 J. C. Nickerson, C. L. Bloomcamp, and R. M. Pereira2 Introduction even as far north as Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, where a colony nested in an apartment block on the Assiniboine The ghost ant, Tapinoma melanocephalum (Fabricius), River (Ayre 1977). Ghost ants populations and infestations was considered a nuisance ant that was only occasion- are reported in many areas of the United States, as well as in ally important as a house pest within Florida as late as Canada, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean Islands. 1988. Field populations were confined to South Florida, although active colonies had been reported as far north as Gainesville, in Alachua County (Bloomcamp and Bieman, personal communication) and Duval County, (Mattis et al. 2004). But by 1995, if not before, the ghost ant was common in central and southern Florida and had been elevated to major pest status (Klotz et al. 1995). In more northerly states, infestations are confined to greenhouses or other buildings that provide conditions necessary for survival, as the ant is a tropical species either of African or Oriental origin (Wheeler 1910). However, this introduced ant species is so widely distributed by commerce that it is impossible to determine its original home (Smith 1965). Distribution Figure 1. Worker of the ghost ant, Tapinoma melanocephalum (Fabricius), lateral view. The ghost ant is associated with a complex of ant species Credits: Phillip Bernie (used with permission) known as “tramp ants” that is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical latitudes worldwide. In fact, T. melanoceph- In the United States, the ghost ant is well established in alum was once referred to simply as the “tramp ant.” Colo- Florida and Hawaii, and its range is expanding. -

Food Preferences and Foraging Activity of The

Foraging Activity and Food Preferences of the Odorous House Ant (Tapinoma sessile Say) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) by Laura Elise Barbani Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Life Sciences / Entomology Dr. Richard D. Fell, Chairman Dr. Dini M. Miller Dr. Donald M. Mullins June 2003 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Odorous house ant, Food Preferences, Foraging, Tapinoma sessile Copyright 2003, Laura Elise Barbani Foraging Activity and Food Preferences of the Odorous House Ant (Tapinoma sessile Say) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Laura Elise Barbani ABSTRACT Foraging activity and food preferences of odorous house ants (Tapinoma sessile (SAY)) were investigated in both the field and laboratory. Foraging activity was examined in the field from April to September 2001 by attracting T. sessile to feeding stations containing a 20% sucrose solution. Ant foraging activity was recorded over a twenty-four hour period along with ambient temperature to examine possible correlations with ant activity patterns. Results indicate that foraging activity may be influenced by both time and temperature. In April and May when temperatures dropped below approximately 10 LC, little or no foraging activity was observed. However, in the summer when temperatures were generally higher, foraging activity was greater during relatively cooler times of the day and night. Under laboratory conditions, T. sessile was attracted to feeding stations and foraged throughout the day and night at a constant temperature of approximately 25LC. Evaluations of seasonal food preferences using carbohydrate, protein and lipid samples were also conducted throughout the spring and summer. -

Yes, That Ant Does Smell Like Blue Cheese 8 June 2015, by Matt Shipman

Yes, that ant does smell like blue cheese 8 June 2015, by Matt Shipman At the annual BugFest event held at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Penick did a survey. He asked hundreds of people to smell T. sessile and fill out a survey on what they thought the ants smelled like. The winner? Blue cheese. And this is where the science really comes in. To see if T. sessile really smelled like blue cheese, Penick got in touch with his friend Adrian Smith, a postdoc who studies chemical communication in Odorous house ants. Credit: Adrian Smith, social insects at the University of Illinois at Urbana- http://www.adrianalansmith.com/ Champaign. To analyze the characteristic smell of odorous house ants, the researchers placed an SPME fiber If you live in the United States, you've probably in a container with the ants to absorb their odor. seen an odorous house ant (Tapinoma sessile) – They then did the same with a container full of blue one of the most common ants in the country. And cheese and a container containing coconut. The for more than 50 years they've been described as researchers then analyzed the chemicals caught by smelling like rotten coconut. But Clint Penick thinks the SPME fiber using gas chromatography-mass they smell like blue cheese. And he can prove he's spectrometry. right. It turns out that the scents of blue cheese and T. Penick is postdoctoral researcher at NC State. sessile are both caused by the same class of Most of his work revolves around ants, and for chemicals, called methyl ketones. -

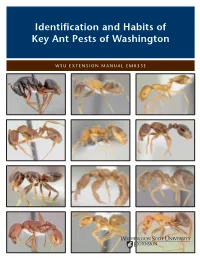

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington WSU EXTENSION MANUAL EM033E Cover images are from www.antweb.org, as photographed by April Nobile. Top row (left to right): Carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc; Velvety tree ant, Liometopum occidentale; Pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis. Second row (left to right): Aphaenogaster spp.; Thief ant, Solenopsis molesta; Pavement ant, Tetramorium spp. Third row (left to right): Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile; Ponerine ant, Hypoponera punctatissima; False honey ant, Prenolepis imparis. Bottom row (left to right): Harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex spp.; Moisture ant, Lasius pallitarsis; Thatching ant, Formica rufa. By Laurel Hansen, adjunct entomologist, Washington State University, Department of Entomology; and Art Antonelli, emeritus entomologist, WSU Extension. Originally written in 1976 by Roger Akre (deceased), WSU entomologist; and Art Antonelli. Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily anywhere from several hundred to millions of recognized group of social insects. The workers individuals. Among the largest ant colonies are are wingless, have elbowed antennae, and have a the army ants of the American tropics, with up petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments to several million workers, and the driver ants of between the mesosoma (middle section) and the Africa, with 30 million to 40 million workers. A gaster (last section) (Fig. 1). thatching ant (Formica) colony in Japan covering many acres was estimated to have 348 million Ants are one of the most common and abundant workers. However, most ant colonies probably fall insects. A 1990 count revealed 8,800 species of ants within the range of 300 to 50,000 individuals. -

Tapinoma Sessile and Its Preference for Sour, Sweet, Bitter, and Salty Solutions

Tapinoma sessile and its Preference for Sour, Sweet, Bitter, and Salty Solutions Stephen J Gould (230043795) Biology 102 Section L2 TA: Conn Iggulden ABSTRACT Tapinoma sessile is a common ant species that often nests in close proximity to human structures and food sources which often leads to conflict. This study investigated if ants exhibited preferential forage selection for sweet (sugary) foods when compared to bitter, sour, and salty solutions. Ants were placed in terrariums and induced to choose food sources. Selection was indicated by the mass harvested. Ants showed a high preference for sweet foods when compared to the other foods and the control (water). These findings are significant as they showed that ant preference for sugary foods is high enough to perhaps use sugar to lure ants away from crops. INTRODUCTION Selecting forage is a crucial choice facing an individual in its quest for survival. Individuals choose between foods that vary in abundance, accessibility, palatability, and nutritional value. Selecting optimal forage, can lead to high energy intake, a healthier individual, higher fitness, and increased reproductive fitness (Pyke et al 1977). Suboptimal selection can lead to low energy intake, poor health, low reproductive fitness and death. These consequences are severe enough that forage selection is not random and represents an evolutionary derived survival strategy (Pyke et al. 1977). This study determines the foraging preference of a common, native species of ant, the odorous ant ( Tapinoma sessile), by measuring its preference between sweet, salty, sour, and bitter solutions. T. sessile is commonly seen nesting in various locations from sandy beeches, to swamps, bogs and houses.